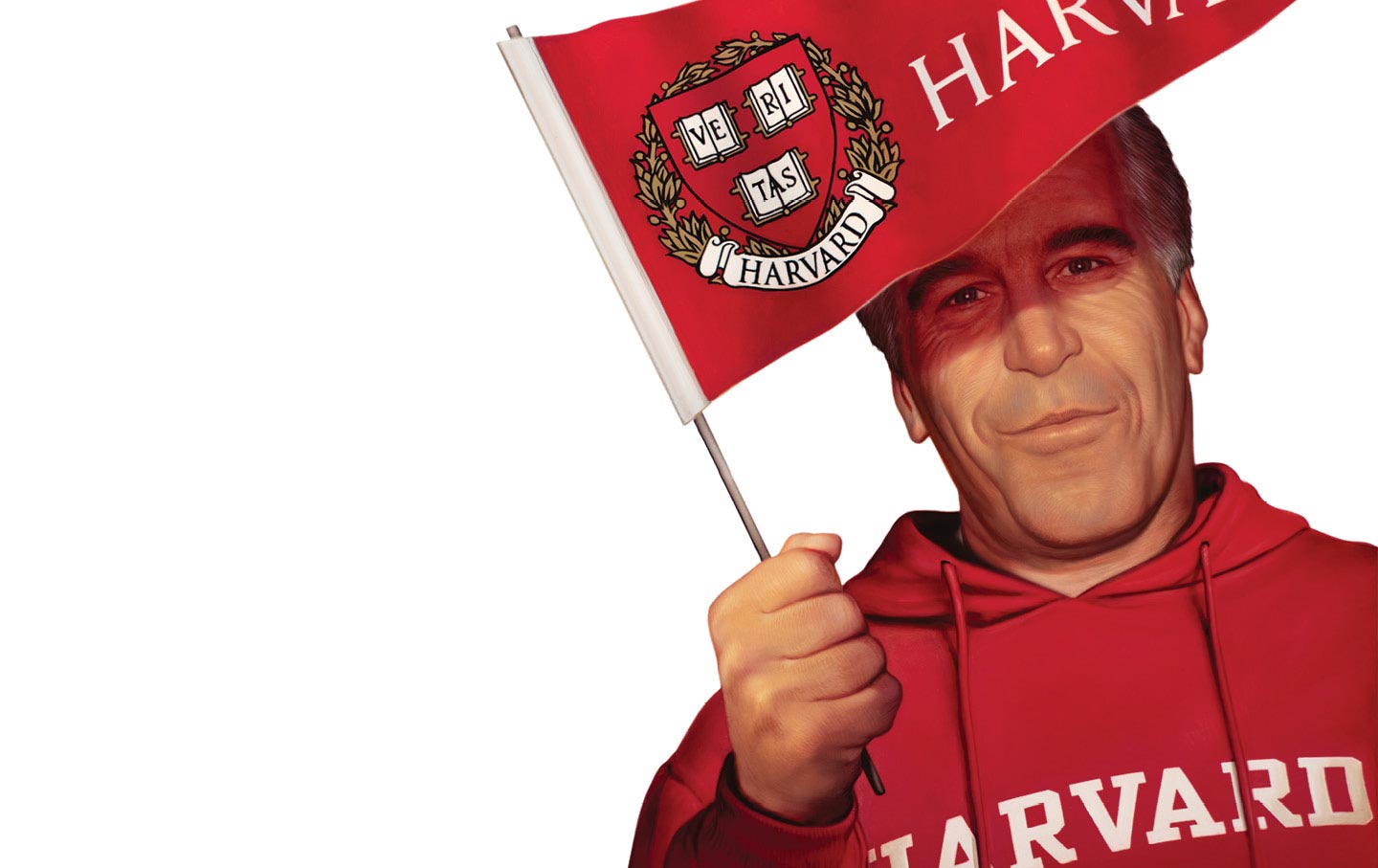

Meet William Ackman, America’s Most Entitled Donor

The hedge-fund activist’s attacks on Harvard and Claudine Gay have gotten much notice; less attention has been paid to the toll his financial activities have taken on the country.

The reaction to the October 7 Hamas attack on Israel has exposed the influence of university donors like never before. For years, their power was wielded behind the scenes, but it has lately been on naked display, with even the august Harvard Corporation forced to bow before it.

Within days of the attack, the Wexner Foundation—named after Leslie Wexner, the billionaire founder and former CEO of Limited Brands, who over the years has given the Harvard Kennedy School more than $42 million and who has a building there named after him—announced that it was ending his support for the university after 34 years, charging it with “tiptoeing” over Hamas’s assault on Israel.

Idan Ofer, the son of an Israeli shipping magnate who is worth an estimated $15 billion—and who also has a Kennedy School building named after him—resigned, along with his wife, Batia, from the Dean’s Executive Board over what they said was President Claudine Gay’s lukewarm response to the Harvard student letter blaming Israel for the October 7 slaughter. And Len Blavatnik, an Odessa-born commodities mogul who is worth more than $30 billion and who has given Harvard at least $270 million, announced in December that he was putting future donations on hold until the university addressed antisemitism on campus.

Most visible of all has been William Ackman. The hedge-fund executive campaigned tirelessly against all three of the university presidents who testified before Congress on December 5, but none more so than Gay. A graduate of both Harvard College and the Harvard Business School who has donated more than $25 million to the university, Ackman repeatedly blasted the Corporation for considering for president only candidates like Gay who met the university’s diversity and equity criteria; demanded that the university release the names of the members of student groups who signed a letter holding Israel solely responsible for the Hamas attack so that they could be denied jobs on Wall Street; and posted a three-and-a-half-minute edited clip of the exchange between Representative Elise Stefanik and the university presidents that garnered more than 100 million views, helping fuel the outrage against them.

The brazenness of these efforts has gotten much comment. But there’s another aspect of donor influence that has escaped notice, and that’s the immunity from scrutiny their philanthropy helps secure.

Bill Ackman belongs to a volatile cohort of Wall Street actors known as hedge-fund activists. Unlike most hedge-fund managers, who relentlessly buy and sell stocks in a bid to beat the market, activists buy large stakes in a few publicly traded companies and seek to drive their stock prices up (or, in the case of short-selling, down), then sell off their shares for a large profit. In many cases, they seek changes in a company’s operations and threaten to wage proxy fights to bring them about. Their demands include slashing costs, restructuring management, selling off assets, and redistributing cash to shareholders in the form of dividends and buybacks. Though few in number, these activists (whose ranks include Carl Icahn, Paul Singer, Daniel Loeb, Nelson Peltz, and David Einhorn) have come to wield enormous economic power.

Even within this group, Ackman stands out for his chutzpah, flair, and craving for the limelight (though in a 2021 letter to shareholders he said he was moving away from the “noisiest” forms of activism in favor of a more “constructive” approach). He and his company, Pershing Square Capital Management, are known for both their spectacular hits and sensational misses. Ackman has had enough of the former to amass a fortune of around $4 billion, but, win or lose, he often leaves carnage in his wake.

Take JCPenney. Like many retailers, the department store chain struggled to adjust to online shopping, but Ackman felt he knew the way forward. In October 2010, he and a partner bought 26 percent of the company’s stock. The following February he gained a seat on its board and engineered the replacement of CEO Myron Ullman with Ron Johnson, a senior vice president at Apple who had guided its retail strategy. Building on Ackman’s ideas, Johnson at great expense created chic boutiques within JCPenney’s stores. He also eliminated coupon discounts, a longtime company tradition. These changes alienated longtime customers while failing to attract new ones, and both traffic and sales plunged. Employees chafed at the constant changes and what they saw as Johnson’s imperious style—especially after it was revealed that he commuted weekly by private jet from California, where he lived, to the company’s headquarters in Plano, Tex. Seventeen months after Johnson became CEO, the company dismissed him and reinstated Ullman.

On August 13, 2013, Ackman resigned from the board, and by the end of the month he had sold off his entire stake in the company, at a loss of more than $700 million. Heavily indebted, JCPenney itself continued to founder. In May 2020, amid plunging sales caused by the pandemic, the company filed for bankruptcy. As part of its restructuring, it announced that it was closing about a quarter of its 846 stores, costing thousands of its 85,000 employees their jobs. Forbes, in a piece on the five people most responsible for JCPenney’s demise, ranked Ackman first. “A monumental mistake, unprecedented in modern American retailing history,” it called his role. “It can be said unequivocally that had he not done what he did to JC Penney, it would not have filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy.”

Even when Ackman wins, America often loses. In the fall of 2011, for instance, Pershing Square acquired 14 percent of the stock of Canadian Pacific Railway, becoming its largest shareholder. The company carried grain, coal, chemicals, forest products, and consumer goods across a nearly 15,000-mile network stretching from Vancouver to Montreal and south to US industrial centers extending from Kansas City to Philadelphia. Studying the company’s numbers, Ackman concluded that it was stodgy, outdated, and inefficient, creating a drag on both its profits and share price. After buying the stock, he launched a long proxy battle to oust the company’s CEO and chairman. Both eventually agreed to step down, clearing the way for Ackman to appoint his own board members (including himself) and to install a new chief executive, E. Hunter Harrison.

The most prominent figure in railroading over the previous half century, Harrison had developed a system of precision scheduling that used a rigorous data-based approach to reduce idling and boost cargo efficiency. At Canadian Pacific, he imposed an aggressive cost-cutting program that required many fewer locomotives and reduced the workforce by more than 6,000 during his four-and-a-half-year reign; he also tightened the disciplinary system, imposing heavy penalties for even minor infractions. Operating expenses fell sharply; profits nearly quadrupled; and the stock price rose threefold. In 2016, Pershing Square sold its remaining stake in the company, netting a total of $2.6 billion over five years and helping to make Ackman a celebrity.

Based on Canadian Pacific’s example, precision scheduled railroading (PSR) became the norm across the freight industry. The result was reduced work crews, long hours, cutbacks in time for sick leave, limited training, high employee turnover, deferred maintenance, and trains of more than a mile long (causing extended waits at crossings). “Railroads are slashing workers, cheered on by Wall Street to stay profitable amid Trump’s trade war,” ran a January 2020 Washington Post headline. According to the Post, more than 20,000 rail jobs had been lost in the previous year, and while the slump was due in part to Trump’s trade policies and to such longer-term trends as America’s diminishing reliance on coal, the losses were being exacerbated by the industry’s embrace of PSR.

“Shareholders at railroads are looking at the financial success of PSR and now every single big railroad is trying to adopt some form of this,” Peter Swan, an associate professor of logistics at Pennsylvania State University at Harrisburg, told the Post. “If you’re trying to save money, you cut people like crazy.” Much of the savings was returned to shareholders in the form of dividends and buybacks. In a September 2021 speech, Martin Oberman, chairman of the Surface Transportation Board (the federal agency that regulates freight rail), criticized the railroads for their unrelenting efforts to reduce operating expenses; since 2010, he said, the companies had paid out an “astounding” $183 billion in dividends and buybacks—far more than the $138 billion they had invested in infrastructure.

The 2022 rail labor dispute was brought on in part by the draconian cost-cutting measures imposed by precision railroading–obsessed executives, which included strict attendance policies that effectively required workers to remain on call for weeks at a time. The workers got a 24 percent pay raise over five years but only one day of sick leave a year rather than the 15 they had sought, with President Biden intervening to support the deal. The calamitous derailment of a Norfolk Southern train carrying hazardous materials that occurred near East Palestine, Ohio, on February 3, 2023, was caused in part by the reduction in work crews mandated by PSR.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Bill Ackman was not personally responsible for such developments, of course, but the changes he helped introduce at Canadian Pacific had the long-term effect of making railroading more hazardous while padding Wall Street portfolios. It’s a stark example of the growing power of the financial sector in the US economy—and the accompanying transfer of wealth from workers to shareholders.

Given the part that hedge-fund activists have played in that transfer, you would think that they would be the subject of close study at an institution like Harvard. But that’s not the case. At neither its economics department nor its business school nor the Kennedy School does this group of individuals receive much attention. And when they do, it’s often admiring. A 2015 case study at the Harvard Business School, for instance, posed the question of how Ackman should raise capital for a “sizable new portfolio position.”

“Although always activist in nature,” the study’s abstract states, “Ackman and his fund [have] in recent years become substantively involved in the management of portfolio companies, often working to drive shareholder value by improving operating performance.” Increasing shareholder value is thus unquestioningly accepted as the main yardstick of success.

Ackman is a good friend of Harvard economics professor David Laibson. From 2015 to 2018, Laibson served as the chair of the economics department, and for the last several years he (along with Jason Furman) has co-taught Ec 10, the storied introductory economics course at the school. Both Laibson and Ackman were members of the Harvard Class of 1988, and on the occasion of their 25th reunion, Laibson persuaded Ackman to fund the Foundations of Human Behavior Initiative that he was organizing. Ackman agreed to donate $17 million for three professorships and a research fund. (He also endowed the chair held by Raj Chetty, a renowned Harvard economist who directs the Opportunities Insight research unit.) This is how Ivy League funding networks work: A well-placed professor has a friend on Wall Street who can underwrite his favored programs.

Behavioral economics (of which the Laibson initiative is an example) is an anodyne field that seeks to explore the psychological, social, economic, and biological mechanisms that influence human behavior. (A good example is Nudge, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s book about how people can be prodded through subtle means of persuasion to change their behavior in a more healthful and productive direction.) Behavioral economists rarely examine deeper structural forces or the ways in which increasing shareholder value magnifies income inequality, the concentration of wealth, and the power of the .01 percent.

Over the past quarter-century, behavioral economics has captured economics departments across the country. The lack of challenge it poses to the prerogatives of the financial sector helps explain its popularity. This ideological preference is one of the reasons a figure like Ackman escapes scrutiny, but his contributions to his alma mater and his ties to its faculty provide an added layer of protection.

(Lively discussions of hedge fund activism do occasionally occur at the Harvard Law School, which hosts a Project on Hedge Fund Activism—part of its broader Program on Corporate Governance. Ackman sits on the program’s advisory board.)

After Gay’s resignation, Ackman, in an exultant post on X, denounced the reign of DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) at Harvard, calling it “inherently a racist and illegal movement” to which “a meritocracy is an anathema.”

“Harvard must once again become a meritocratic institution which does not discriminate for or against faculty or students based on their skin color,” he wrote. Ackman also extolled his own efforts to help members of disadvantaged communities “by investing several hundreds of millions of dollars of philanthropic assets” in economic development, criminal justice reform, poverty reduction, healthcare, education, workforce housing, and charter schools.

Ackman did not mention his support for Dalton, an elite prep school on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. During the school’s centennial fundraising campaign (which lasted from 2015 to 2020 and was led in part by Anderson Cooper), the Pershing Square Foundation contributed more than $10 million of the total $108 million raised. Dalton is one of a dozen or so schools favored by New York’s most privileged families, partly because of the high proportion of graduates who are admitted to Ivy League schools (about 30 percent in Dalton’s case).

Two of Ackman’s daughters by his first marriage are graduates of the school, and in 2016 one of them entered Harvard. How much of an advantage did she have by virtue of attending Dalton and having a father who is both an alumnus of—and major donor to—Harvard? These are questions that Ackman, when discussing meritocracy, never seems to consider. (Dalton was the featured school in Caitlin Flanagan’s 2021 Atlantic story “Private Schools Have Become Truly Obscene,” in which she described how such schools “breed entitlement” and “entrench inequality.”)

In 2019, Ackman had another daughter, with his second wife, Neri Oxman, an artist and architect who until 2021 was the Sony corporation career development professor and an associate professor of media arts and sciences at the MIT Media Lab (and who was born in Israel). She and Ackman were connected by Martin Peretz, the former owner of The New Republic, who’d been a professor of Ackman’s at Harvard and one of the first investors in his fund (another example of how insider networks work).

After they were engaged, Ackman took Oxman to see the four apartments he was about to buy on West 77th St. across from the American Museum of Natural History, which he planned to combine into a penthouse. (This was in addition to the apartment he owned in the nearby Beresford co-op building; his duplex penthouse at 420 West Broadway; his 13,500-square-foot penthouse condo at One57 in Midtown Manhattan for which he paid $90 million; and his beachfront estate in Bridgehampton.) Two days after Gay’s resignation, Business Insider ran a story charging Oxman with plagiarizing multiple sentences and paragraphs of her doctoral dissertation at MIT, completed in 2010.

Vigorously defending his wife, Ackman announced that he was launching a plagiarism review of all MIT faculty as well as of its president, Sally Kornbluth, and called for similar reviews at other universities, which, he said, would lead to “the inevitable destruction of the reputations of thousands of faculty members.” He welcomed the prospect of “getting rid of tenured faculty” through the use of AI as part of a much broader assault on the U.S. system of higher education. In short, Ackman is applying to American universities the activist techniques he long directed at American corporations.

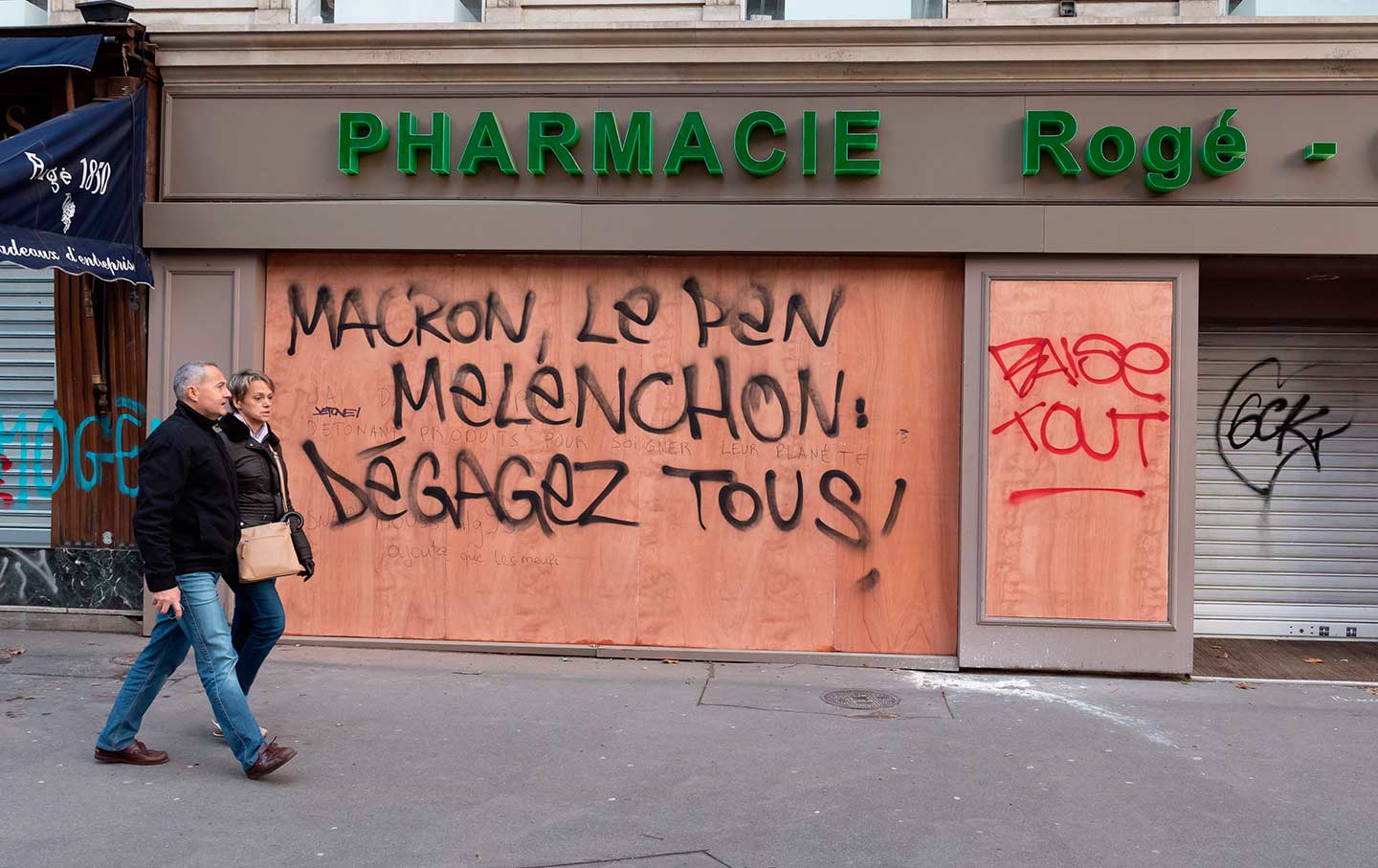

There’s one thing that Ackman and other detractors of Claudine Gay have in common with her supporters: an obsessive focus on race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation. By comparison, they pay little attention to class, inequality, the concentration of wealth, and how America’s financial class has amassed so much power that it can bring down a Harvard president.

More from Michael Massing

If You Don’t Know Who Ken Griffin Is, You Should If You Don’t Know Who Ken Griffin Is, You Should

How the press keeps us in the dark about the new Gilded Age.

How Jeffrey Epstein Captivated Harvard How Jeffrey Epstein Captivated Harvard

And how the university has yet to give a full accounting.

Does the Harvard Kennedy School Serve the People—or Power? Does the Harvard Kennedy School Serve the People—or Power?

The elite public policy and government school may have reversed course on Kenneth Roth, but its deep ties to Wall Street and Washington remain.

Why the Godfather of Human Rights Is Not Welcome at Harvard Why the Godfather of Human Rights Is Not Welcome at Harvard

Kenneth Roth, who ran Human Rights Watch for 29 years, was denied a fellowship at the Kennedy School. The reason? Israel.

The Virus, the Press, and the Comfortable Class The Virus, the Press, and the Comfortable Class

Liberal and conservative elites aren’t grappling with the pandemic’s toll on working-class people—and the impossible choices they’re forced to make.

The Populism Problem at the ‘Times’ The Populism Problem at the ‘Times’

The paper of record needs to remember that it’s not exclusively a right-wing phenomenon.