Over the past decade, I thought I had finally figured out how to earn a living as a disabled person. I work as a speaker, a consultant, and an activist, but writing was always my first love. I started writing professionally in my late 20s, and since then my work has been published on blogs, in magazines, and in books. I have taken tremendous strides in this aspect of my career.

But in 2020, when the pandemic shook all of our lives, progressive news sites began shutting down in droves. It has been devastating to witness over the past three years. While the 2010s might not have been the heyday of the business-class-flying, glossy-magazine reporter, that decade’s media allowed many of us—disabled and non-disabled writers alike—to write and be paid for it. It’s disheartening to know that many aspiring journalists and journalism school graduates are having to give up before they start, given the dwindling opportunities for writers, editors, and fact-checkers.

As a disabled writer, I’m no stranger to working hard and getting creative to pursue a dream no matter the circumstances. Indeed, the obstacles for people like me are endless: workplace discrimination; inaccessible job sites for people who are wheelchair-bound, as I am; poverty wages (also known as “subminimum wages,” where it is still legal for employers to pay a disabled person less than the minimum wage, and some workers are paid pennies on the dollar); and income restrictions for public benefits that make it nearly impossible to earn enough to live comfortably.

Despite the barriers that the journalism industry has raised for disabled writers, writers of color, and LGBTQ+ writers, members of those marginalized groups have led the way toward a more inclusive approach to the coverage of disability and disability justice. Historically, news outlets have treated disability and related topics as “special interests” rather than as facets of the way our society operates. The way in which disability has been consigned to niche coverage, along with the tiny number of staff roles filled by disabled folks in an industry where jobs are already scarce, has made it difficult for multiply marginalized writers to cover disability or to branch out and cover other stories from our perspective. Squeezing out disabled writers who have so much insight to offer, especially into the injustices, biases, and discrimination they face, is an obstacle that the media industry should not only acknowledge but actively address.

My journey to becoming a writer started after I graduated with a master’s degree in social work in 2012. I knew that my options were limited. Many of the jobs available to social workers at that time required them to do home visits and to drive, which presented a problem for me since most homes aren’t wheelchair-accessible and I don’t drive, because of the cost of accessible vehicles. Given such limitations, it made more sense for me to seek work that I could do from home. I decided to start blogging for a social work outlet that needed someone to write about the societal issues that disabled people face in the United States. I wrote about everything from the school-to-prison pipeline and how it affects disabled students to how social media helps disabled people find community. A year later, I founded an organization called Ramp Your Voice! and began blogging about the intersection of disability rights, social work, and race. After three years, I was able to turn the recognition I had received through my writing at Ramp Your Voice! into freelance gigs at digital outlets. By the fall of 2020, I had become a regular contributor to the independent news outlet Prism.

While the business of freelance writing has evolved over the past decade for all writers, disabled writers—particularly those who are multiply marginalized like me (along with being disabled, I am also a Black woman)—face a unique set of issues. In addition to being shut out of most full-time roles, we must consider the outlets we write for deliberately; in particular, we need to know to what extent their editors know or are open to learning about disability, and whether we will be able to tell our full story without it being edited down to fit a narrative people are more comfortable with.

Ableism—the social prejudice against disabled people—is a barrier disabled people have faced since the beginning of time. It is prevalent in journalism primarily because storytellers often ignore lived realities in favor of stereotypes and simplified sketches. This distortion is concerning for disabled journalists, because people read news for “the truth” and often take specious narratives as accurate. Magazines, newspapers, and blogs often make missteps that contribute to the public’s misunderstanding of disabled people, including by emphasizing inspiration porn (such as an ambulatory wheelchair user who is able to stand or walk for the first time); downplaying mercy killings by highlighting the elimination of the “burden” on caregivers; disregarding the societal barriers we face in experiencing violence and discrimination in public spaces; and allowing parents and caregivers to be the voice for a disabled person without engaging with that person directly.

In addition to handling these stories recklessly, many outlets continue to resist updating the language they use to describe disabled people, which has been a major point of focus for us, especially with the media’s increased reliance on automation. The preferred language used by many in the disabled community is identity-first language, which puts the disability first in describing a person—“disabled person” rather than “person with a disability,” for example. News organizations don’t often adhere to this, and their failure to do so will keep the industry behind, while continuing to frustrate those who have worked hard to push language forward.

While writing for money is hard for everyone in media today to pull off, the financial realities for disabled writers are particularly distressing. Because of the outlets’ own budget crunches, freelance writers often have to press them to pay and to do so on time. In general, disabled workers, including disabled writers, have historically been paid lower rates. We need jobs that not only pay well but that can also support the medical requirements we may have to cover out of pocket in order to sustain our quality of life.

What I’m describing is what we call the “crip tax”—all the extra costs that disabled folks have to take on, in the form of services and tools, in order to live more accessibly. A household with a disabled adult needs an average of 28 percent more income—an extra $17,690 per year for a typical US household—in order to achieve the same standard of living as a comparable household without a disabled member. Earning a livable wage for me means making enough money to repair my wheelchair and save for new hearing aids, to name just a few of my needs. I came off the rolls of Social Security seven years ago; catching up on saving and having the means to take care of myself without significant limits is a new concept to me. Like many of my disabled peers, I am financially behind my non-disabled counterparts. Earning a wage looks different when the wage has to sustain a different kind of life.

Being paid a livable wage should not be an exception but the reality for everyone in the workforce. However, for freelancers who are writing for outlets that may pay as little as $100 a story, chasing stories and money is often the hard reality. Too often, writers are scrambling to pitch to multiple outlets to find the one that will give them rates they can live with. And often, they can’t. As s.e. smith, a California-based freelance journalist, put it recently, as a disabled writer, “I watch outgoing expenses exceed my income.”

Such financial barriers are making those of us who remain in this industry wonder how much longer we can last. For disabled writers, who are already forced to spend more money day-to-day to survive, the outcome is particularly crushing. “Freelancing built my career as a disabled journalist by allowing me to work on my own schedule,” smith told me. “It may also be the thing that drives me out after more than 15 years.” For freelance journalists, who have always had to prove themselves through tireless, poorly compensated efforts, work has gotten much harder. And when you start at the bottom of the rung, “hard” takes on a whole new meaning.

The current political environment has been an additional hurdle. As we stare down another presidential election, conservatives are more emboldened than ever, creating a dangerous environment for multiply marginalized writers who share their stories. Pieces about disability may be deemed by those on the right as “too woke” and not in line with their agenda to “return” to an America where such stories and individuals did not gain widespread reach. (Look no further than Fox News to confirm that any company or person who discusses or depicts disabled identities in a positive light is at risk of being lambasted.) As a result, outlets that give space to disabled voices may face more resistance from the public. The prospect of an outlet being pressured to reduce, shift, and/or abandon inclusive storytelling is a scary one.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →There is also the safety of the writers. The risk of being targeted for harassment as a disabled individual remains high. Keah Brown, a disabled Black woman who’s a freelance journalist, told me recently that after she wrote an essay for Inverse about how superhero stories have a disability problem, she “received actual death threats and slews of e-mails calling me all sorts of ableist and racist slurs.” I, like many disabled people with Internet footprints, have been similarly harassed. Magazines, newspapers, and media websites that remain silent and unprepared for this will face consequences when it comes to acquiring and retaining multiply marginalized writers.

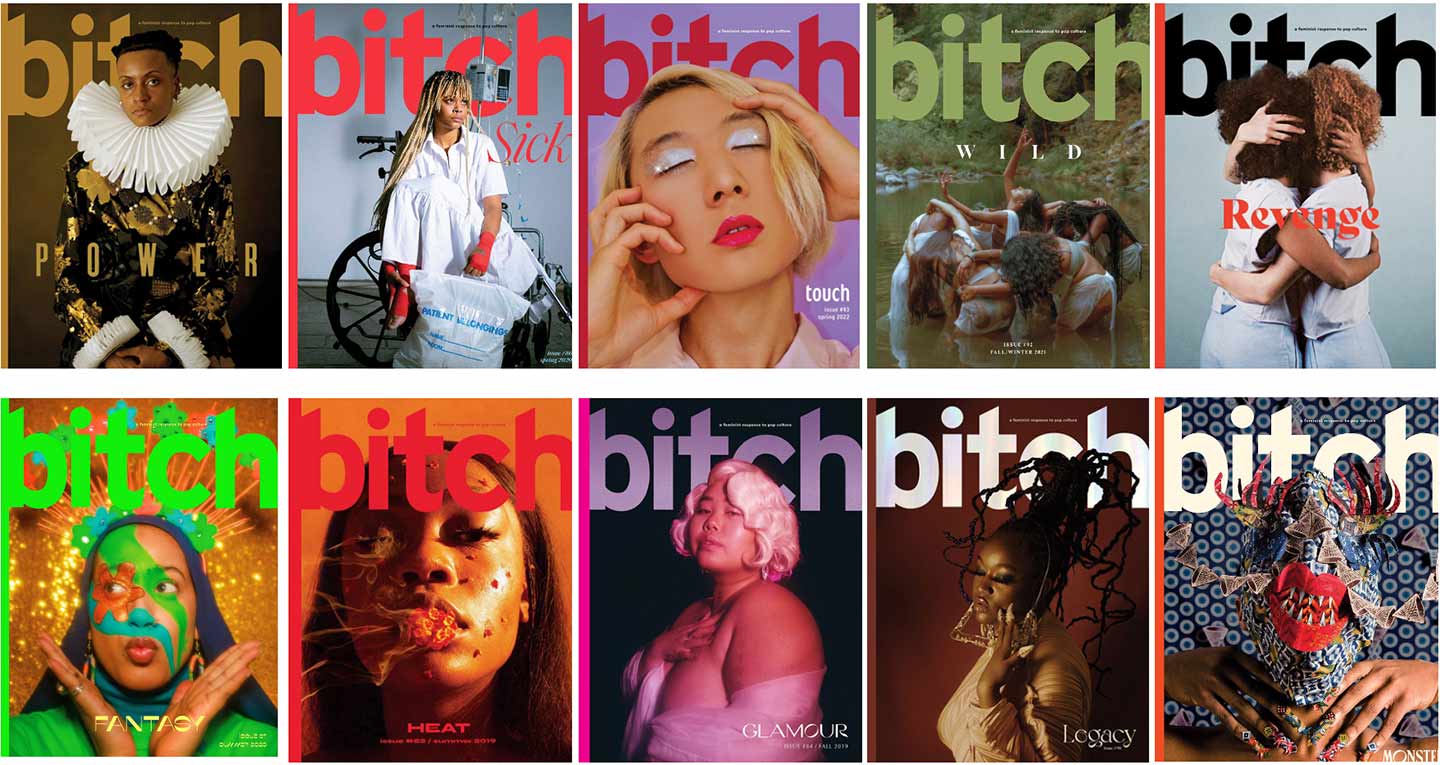

Throughout my career, I have been lucky to work with outlets that have transformed the freelancing experience for disabled writers by recognizing that they can offer an undeniable value to journalism. Some of those websites include Teen Vogue and Prism. But the one that feels closest to my heart is Bitch magazine, the first website that gave me an opportunity to interview one of my favorite celebrities, Rachel True. It was my first celebrity interview and unrelated to the disability writing I am typically given a lane for.

Writing about something other than disability rights—one of the few topics editors often trust disabled writers to cover—has become a privilege when it shouldn’t be. Ableism has put the onus on disabled writers to correct the record about our lived realities. Bitch did that for so many of us before it ceased operating in June of 2022, and its loss continues to be felt. The closures of progressive outlets in the past few years have been difficult for everyone in journalism, but for multiply marginalized people, the few opportunities we started with are now even fewer. Many of us have been left wondering where we can receive editorial care.

For those of us in the industry, the questions about where journalism will be in five or 10 years are ever-present. And given the ableism and misguidance from uninformed editors who handle disability-centered content, the cesspool of comment sections, and the possibility of being doxxed, many of us are weighing whether it is actually worth it. Amid the revival of interest in blogging with tools like Substack and Tiny Letter, the choice of writing for oneself as many of us did a decade ago is looking more appealing, despite the financial risk it poses.

As a social worker, I have always been motivated to support not only myself but others. My vision for my future as a Black disabled writer includes working with newsroom leaders to address the lack of stories about and by disabled folks, while still writing for outlets that respect my voice—and, importantly, using my contacts to support and leverage the work of disabled writer colleagues.

This is a critical moment for journalism that will determine not only its fate in terms of legitimacy and relevance, but also in regard to who is afforded the chance to tell their stories. Prioritizing free speech, facts, and ethics in our narratives and revitalizing an industry in a ghastly era are the responsibilities not only of disabled people like me, but of all of us—writers, editors, outlets, donors, and readers.

Thank you for reading The Nation

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read, just one of the many incisive, deeply-reported articles we publish daily. Now more than ever, we need fearless journalism that shifts the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media.

Throughout this critical election year and a time of media austerity and renewed campus activism and rising labor organizing, independent journalism that gets to the heart of the matter is more critical than ever before. Donate right now and help us hold the powerful accountable, shine a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug, and build a more just and equitable future.

For nearly 160 years, The Nation has stood for truth, justice, and moral clarity. As a reader-supported publication, we are not beholden to the whims of advertisers or a corporate owner. But it does take financial resources to report on stories that may take weeks or months to properly investigate, thoroughly edit and fact-check articles, and get our stories into the hands of readers.

Donate today and stand with us for a better future. Thank you for being a supporter of independent journalism.

More from The Nation

When Death Is the Best Choice, Is It a Choice at All? When Death Is the Best Choice, Is It a Choice at All?

Disabled Canadians need support, but without proper government funding, voluntary death through MAID may be their only option.

Rationing of Medical Equipment Is Costing Disabled People Their Lives Rationing of Medical Equipment Is Costing Disabled People Their Lives

With the government refusing to make medicine and medical equipment accessible, sick, and disabled people have to rely on each other for support.

The Disabled Community Doesn’t Want Your Pity The Disabled Community Doesn’t Want Your Pity

Why former telethon participants are protesting the return of the Muscular Dystrophy Association’s most famous fundraising effort.