Halfway into my training to become an intensive care unit physician, I gave birth to my son, Finnegan. My medical training also coincided with the Covid-19 pandemic. I was in the third and final year of my internal medicine residency at Bellevue Hospital in New York when the initial Covid surge of spring 2020 overwhelmed the city and its hospitals. A few months later, I moved to another hospital in the city to begin a three-year fellowship in pulmonary and critical care medicine. When I made the commitment in the summer of 2019 to specialize in lung problems and ICU medicine, no one had heard of Covid-19. Yet that disease would define my initiation into the field.

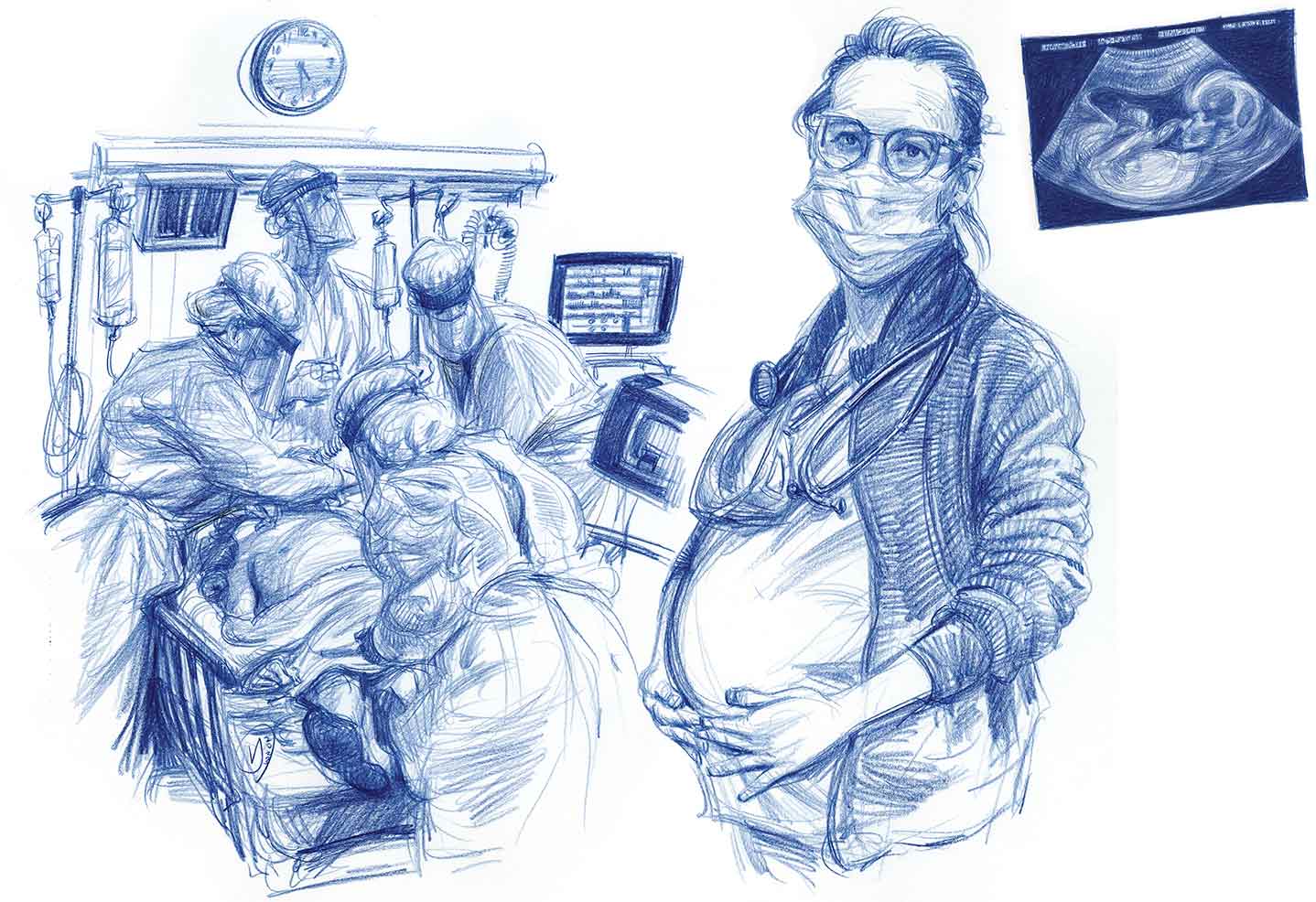

One year into the pandemic, in the spring of 2021, I found out I was pregnant with Finn. On my overnight shifts in the ICU, when few colleagues were around, I would close the door to the fellows’ office, squeeze cold gel onto the ultrasound probe, place it on my abdomen, and slowly shift my angle until his tiny body came into view.

He was, I admit, alien-like. I was used to seeing infected lungs and poorly functioning hearts with ultrasound. To identify a little foot inside a body cavity was disconcerting at first. But I was soon mesmerized. His legs kicked, his heart beat, and his lungs filled and emptied with fluid in preparation to one day breathe air. Like my patients in the ICU, he was on full life support. Only that support came not from machines but from my body.

In the aftermath of each wave of Covid, we cared for dozens of patients with prolonged critical illness. These were patients who needed the respiratory support of a ventilator for weeks or even months. Some did not survive, but many did. A few of our patients required such deep sedation they were essentially under general anesthesia for months, a kind of limbo between life and death. For others, the trajectory toward recovery was more straightforward but punctuated with setbacks like hospital-acquired infections, muscle wasting, skin breakdown, and delirium.

The slow, methodical care these patients with prolonged critical illness required was a departure from the adrenaline-fueled crises that had drawn me to ICU medicine. Observing the immediate positive effects of a medical intervention—a collapsed lung re-expanded, an unstable arrhythmia slowed to a steady beat, a source of bleeding identified and repaired—is deeply satisfying. It is in those moments as a physician that you are briefly granted the illusion of being in control.

The care of patients with prolonged critical illness unfolds on a slower timescale, consisting largely of what is called supportive care. Though I trusted that we were providing excellent care to our patients, I struggled with not knowing what long-term impact that care would have. Would these patients even survive? If they did, what kind of lives would they have?

Unlike my patients, who might not survive despite receiving the most technologically advanced life support that has ever existed, Finn was growing. If my patients were on the verge of death, he was on the verge of life. Watching his somersaults on the ultrasound screen, I imagined parenthood would be a counterbalancing force to my work, an antidote to so much despair.

In the fall, when my belly was big enough that I had to lean forward to see my feet, I came across Adam Zagajewski’s poem “Try to Praise the Mutilated World.” At that time, I was working closely with my therapist to process the trauma of being on the front lines of Covid. In the evenings, I spent my time decorating Finn’s soon-to-be nursery and ordering baby supplies. I struggled to reconcile these two projects. A line from Zagajewski’s poem created space for both past and future: “You gathered acorns in the park in autumn / and leaves eddied over the earth’s scars.”

I imagined Finn as a toddler, in rubber boots and a big hat, squatting down to pick up acorns on a wet and cloudy day in Central Park, oblivious to the scarred-over wounds of the earth that held him. I could, and would, hold the foreground and the background in my mind at the same time. He would show me that life keeps springing forth, no matter the wreckage.

Finn was born just after Christmas, during the Omicron wave in New York. He was tiny and miraculous. On New Year’s Day, we bundled him up in a green fleece suit with little bear ears and brought him home.

My husband, Ben, was working as a law clerk in Philadelphia that year. He was able to have a few weeks home in New York with us after Finn’s birth. When it was time for him to go back to work, Finn and I went along to live in his small Philadelphia apartment for the remainder of my three-month maternity leave.

It was there that I settled into some kind of parenting rhythm. It was an unsteady and easily disrupted rhythm, but I was doing tasks I was familiar with. Finn had struggled to latch on to me to breastfeed for his first few weeks, and so from the beginning I was pumping breast milk regularly, and Ben and I took turns giving him bottles. In Philadelphia, Finn started to get the hang of breastfeeding, but not enough that I could give up pumping. The rhythm of life was composed of breastfeeding, bottle feeding, pumping, burping, diapering, soothing, napping, bottle cleaning, and pushing Finn in his stroller through Philadelphia’s Old City, where we lived.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Ben and I used an app to keep track of feeding, pumping, and diaper changes, which was surprisingly useful. I always had the feeling I had just fed Finn, and that I had just pumped. The app would set the record straight: that Finn hadn’t eaten in three hours, and it was time to start the cycle again.

It was during one of these cycles—I truthfully can’t remember what time of day, it could have been 2 am or 2 pm—that I had the startling and disorienting realization of just how much the care I was providing for Finn had in common with the care my patients received in the ICU. This was precisely the opposite of what I had believed would be the case. Yet the similarity was striking: Both Finn and my patients were completely dependent on others for their basic needs—nutrition, hydration, safe positioning, temperature regulation, and the cleanup of urine and stool. They were both profoundly vulnerable, unable to meet any of their own needs or even to voice them. They required total care, and that care was a lot of work.

The differences between the care of a healthy newborn and a critically ill patient on life support are, of course, vast. We cared for Finn at home, in a nursery decorated with whales. Holding him against my chest as I rocked him to sleep, I felt a deep sense of security and hopefulness for his future. Normal parental worries aside, I had no reason to believe he would not experience a full life. In contrast, a typical room in the ICU is brimming with machines and devices—ventilators, dialysis machines, IV pumps, pressure monitors, catheters. The patient is nearly engulfed; their future is profoundly uncertain. Hope persists regardless, but what can be hoped for has often been drastically recalibrated or reduced.

Given the many obvious differences between newborn care and the ICU, I can see why I had assumed they would be antitheses. But the fact that their commonality of total care was a revelation also meant that I had been overlooking something fundamental about my profession that had been right in front of me all along.

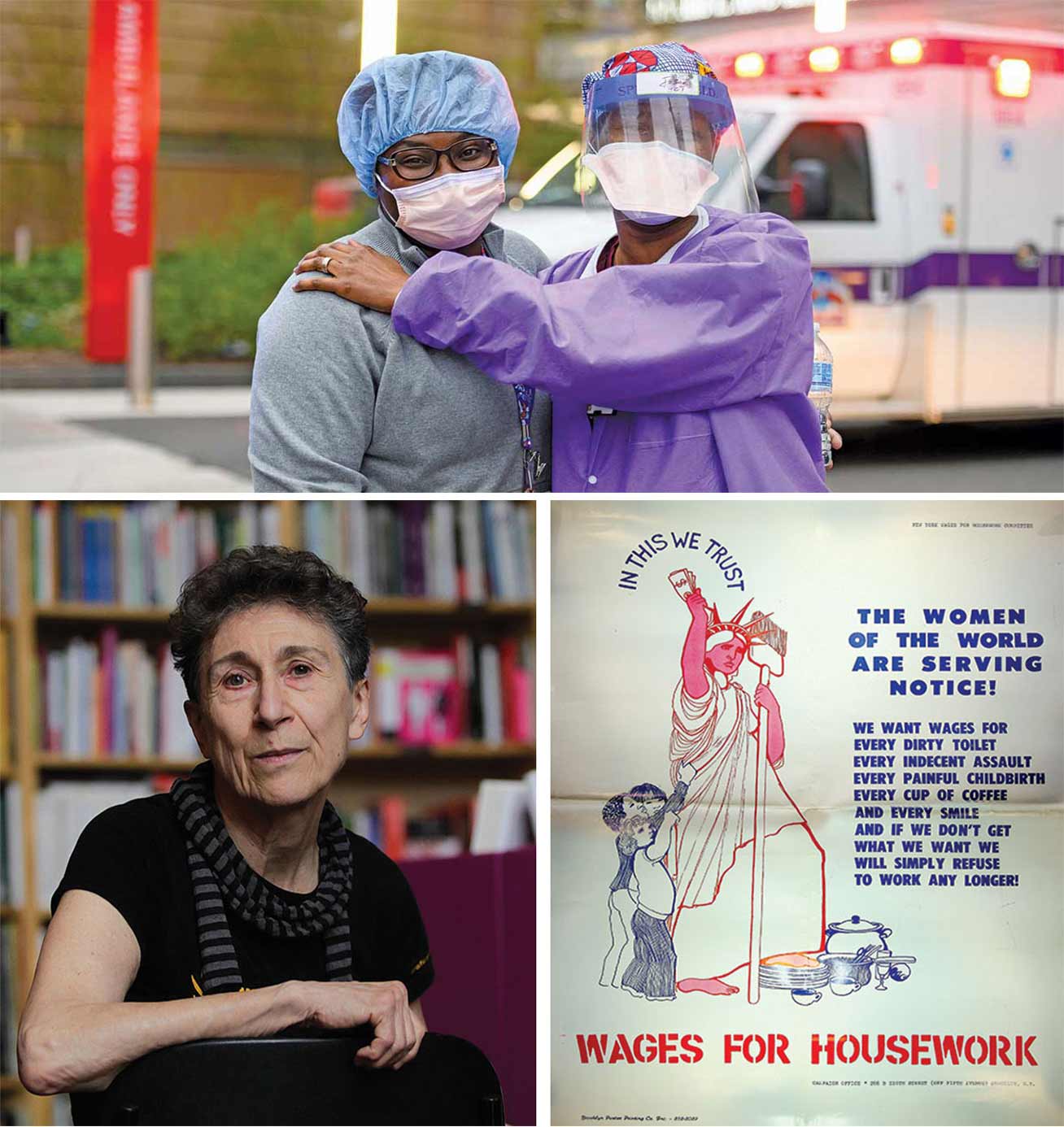

I think the reason I hadn’t fully seen the intensive care labor that my patients required—the continuous cycles of turning, wiping, cleaning, feeding, titrating, monitoring, measuring, recording—is because as a physician, I am, for the most part, not doing this work. This work is done, day in and day out, by nurses. Like so much care work—done by and large by women, especially women of color—it is often invisible, even when it is happening right in front of you.

During my maternity leave, there was a national shortage of infant formula. In response, various media commentators questioned why more women weren’t breastfeeding, especially since breastfeeding is “free.” My life at that time revolved around breastfeeding Finn and pumping extra milk to bottle-feed him. There were moments when I felt just as weary as I had during my toughest moments in residency. The only way this milk could be considered “free” was if my time, my body, and my energy were worthless. I had a glimpse of how dehumanizing it can feel to have your labor rendered invisible.

In the 1970s, the feminist philosopher Silvia Federici led the Wages for Housework (WfH) movement, which called for the remuneration of domestic labor. Federici was raised in postwar Italy by her housewife mother and her philosophy professor father. Her career seemed to mirror his: She became an academic philosopher, with an interest in Marxism and the conditions of workers. But it was her mother’s influence that defined her work.

As Federici was developing her own philosophical and political analyses, her mother urged her to consider the work that housewives did—which her father scoffed at as not real work. In a 2021 interview for The New York Times Magazine, Federici explained: “The working class for me was the factory worker. And my mother several times said to me, ‘You’re always talking about the factory worker as if they’re the only people who work!’… She said that, not my father, who was the teacher, the intellectual, the knowledgeable person. She was the one who told me the things that later became my politics.”

As much as WfH was a demand for actual dollars, it was also a pivotal rethinking of Marxism that recognized capitalism’s exploitation of unwaged labor. “Behind every factory, behind every school, behind every office or mine there is the hidden work of millions of women who have consumed their life, their labor, producing the labor power that works in those factories, schools, offices, or mines,” Federici wrote with Nicole Cox in 1975.

Federici has argued that capitalism succeeded in exploiting domestic labor by propagating the idea that women are naturally inclined to cook, clean, care for children, and serve their husbands and, furthermore, that by living as nature intended, they are fulfilled. While men’s work is labor for wages, women’s work is the labor of love. Federici’s analysis centers on the housewife, but that is only its starting place. “The jobs women perform are mere extensions of the housewife’s condition in all its implications,” she wrote. “Not only do we become nurses, maids, teachers, secretaries—all functions for which we are well trained in the home—but we are in the same bind that hinders our struggles in the home.”

Federici’s work makes visible the connections between newborn care, ICU nursing, and other forms of care labor. Whether paid or unpaid, performed by women or men, this work is what theorists including Federici describe as reproductive labor. In the Marxist sense, productive labor generates goods to be sold for profit in the marketplace, whereas reproductive labor nurtures, feeds, and sustains the workforce.

Medicine, particularly corporatized American medicine, has an analogous division between productive and reproductive labor. The healing professions have had a long-standing tension between curing and caring, with curing seen as the physician’s aim and caring as the nurse’s. In the present day, medical cures are still largely elusive. In many cases, once-deadly diseases, such as HIV and some forms of cancer, are not cured but rather tamed into chronic disease that patients die with rather than of. While physicians can sometimes offer their patients curative treatments, in most cases they provide a kind of care that focuses on slowing disease progression, ameliorating symptoms, and maximizing function.

In the payment structure of American medicine, surgical interventions that aim to fix specific medical pathologies—knee replacement surgeries, for example—are revenue generators. In contrast, care that leans heavily on the cognitive and emotional skills of the physician—a geriatrician painstakingly reviewing a long list of chronic medications with an octogenarian—is time-intensive yet meagerly reimbursed by insurance companies. This valuing of invasive cure over slow and steady care is reflected in physician pay. According to Salary.com, the median salary for an orthopedic surgeon in New York City is more than twice that of a geriatrician: $624,000 versus $255,000. While the geriatricians are still well-off, at that salary difference, an orthopedist would make $11 million more over a 30-year career.

ICU medicine is a paradox on the spectrum of cure-based to care-based medicine. At first glance, it seems entirely focused on cure. Dysfunctional organs are bolstered by various forms of life support—ventilators, dialysis machines, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) provided by heart-lung machines. Each form of life support requires close physician oversight and invasive procedures to initiate, all of which are well compensated by insurance companies.

But this view of ICU medicine covers only a sliver of what goes on in an intensive care unit. When our patients are so sick they require ICU-level interventions, we generally have a very limited sense of how long they will need those interventions—or whether they will even survive. And so while they remain in the ICU, often in a medically induced coma, completely dependent on others for basic human needs like nutrition and hygiene, they receive intensive care—just as the term “ICU” indicates.

It is hard to overstate how much attention and effort go into caring for ICU patients. In optimally staffed ICUs, each nurse will be assigned just one patient or maybe two. Alongside that primary nurse is a cadre of other skilled healthcare workers who optimize the patient’s care to prevent iatrogenesis (harm caused by medical care), preserve function, and otherwise facilitate medical care: nutritionists, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, social workers, wound care nurses, and more. If the patient is on dialysis, they will require a dedicated dialysis nurse. If they are on ECMO, they will require a dedicated perfusionist. While some staffing is reduced on nights, weekends, and holidays, the core components are maintained day and night, 365 days a year.

During the feverish early days of the pandemic in the spring of 2020, we were confronted with the possibility that we would not have enough ventilators for all the patients who needed them. As a resident, I was not informed how many ventilators my hospital had, how many were on the way, or how the threat of shortage was shaping the decisions of when to intubate patients and connect them to a ventilator. But I overheard snippets of higher-level conversations and heard stories through the grapevine that gave credibility to the fear. And I saw that many of our patients who were technically on ventilators were actually on transport ventilators with limited functionality; they were intended for helicopter rescues or transfer between hospitals, not for sustained use. A true ventilator shortage seemed like a real possibility, and that was absolutely terrifying.

Media reporting during the early days of the pandemic fixated on the threat of a ventilator shortage. Though the shortage was a real concern, the power of the machines took on almost mythic proportions, creating a perfect set piece for would-be epic heroes. There were several contenders. In a March 19, 2020, interview on NBC’s Today show, then–New York Governor Andrew Cuomo described the Covid-19 crisis as a war, declaring that “ventilators are to this war what missiles were to World War II.” The New Yorker reported that the blockchain activist Bruce Fenton had gathered 350 volunteers on a Slack channel to crowdsource an open-access ventilator design. (His only apparent medical experience was supporting his son through brain surgery.) Tesla CEO Elon Musk promised to send 1,000 ventilators to California, only for it to later be revealed that the delivered machines were CPAP and BiPAP equipment, which are similar to, but distinct from, ventilators.

What was eerily absent from much of the reporting on the ventilator shortage in March and April 2020 was any acknowledgment of the human skill and labor required not just to operate the ventilators, but to provide total care to the patients on them. The exclusion of care labor from the narrative implied that the nation would return to ICU care as usual once the shortage of machines was solved.

The vast gulf between that narrative and reality had became apparent by the fall of 2020. By that point, material resources like ventilators and personal protective equipment (PPE) were generally better stocked. But hospitals all over the country were faltering under severe staffing shortages, particularly of ICU nurses. The working conditions for nurses became increasingly difficult, with heavy patient loads, pressure to take on more shifts, and the compounding trauma of witnessing so many deaths while large swaths of the public refused to wear masks or get vaccinated. In some hospitals, single ICU nurses were being assigned as many as eight critically ill patients to care for—an arrangement that was incredibly dangerous for the patients and emotionally draining or even devastating for the nurses. Research conducted before the pandemic demonstrated that when an ICU nurse had more than 2.5 patients to care for, the risk of patient death tripled. Based on an analysis of more than 140,000 patients admitted with Covid-19 to 558 US hospitals between March and August 2020, NIH-funded researchers estimated that one in four of the 25,344 patient deaths may be attributable to understaffing during surge conditions.

It’s perhaps easier to understand how a ventilator can save your life than how an appropriate patient-to-ICU-nurse ratio can. As a society, we believe deeply in our great medical technology. Even some physicians and scientists, in the emotional whirlwind of the pandemic, at times placed irrational hope in magic bullet cures.

“The life-saving modalities we already had available to us…were quickly being overlooked for newer, shinier, yet completely unvalidated therapies,” wrote the infectious disease physician Tara Vijayan and the pulmonary and critical care physicians Nida Qadir and Tisha Wang in a blog post for The BMJ in July 2020. “The enormous team effort and painstaking attention to detail required to appropriately manage a ventilator; prevent multi-organ failure; prone patients; and maintain their skin, strength, and consciousness…was not being discussed. The focus was now on finding a single magic bullet to ‘cure’ Covid-19. Such a panacea has never existed in critical illness.”

The constant, meticulous team effort Vijayan, Qadir, and Wang described is the care labor that enables technological developments to restore human health. Technology alone cannot save us. Technology only has a shot at fulfilling its promise to improve human well-being and longevity when it is coupled with the care provided by human beings. We ignore and exploit that care at our peril.

Before I had Finn, I understood children largely through a lens of potential. I loved playing with my nieces and nephews, but I often thought more about who they would become than about who they were at that moment. After Finn was born, friends and family members would occasionally make comments about Finn someday going off to school or learning to read or playing the piano. To my surprise, I had a viscerally negative reaction to those innocuous statements.

Of course, Finn would likely become a child who would go off to school, learn to read, and maybe even play the piano. But that version of Finn would be so different from the little infant cocooned in a baby carrier on my chest that I wondered if he would really be the same person. I realized I wasn’t interested in imagining that future child. I was completely absorbed by Finn in the present. I was learning which slight variations in the pitch and timbre of his cries meant “hungry” and which meant “tired.” I studied his little fingers and stroked his soft back. I took dozens, maybe hundreds, of photos of him sleeping. His life was immeasurably valuable not because of what he would grow into but because he was him, alive in that moment.

That this smoosh-faced, incontinent, nonverbal being was so profoundly precious to me made me think differently about my patients in the ICU. I had imagined parenthood as my antidote for the exhaustion and trauma of ICU work. And in a way, it has been—though not at all as I had imagined. Birthing, nursing, and loving Finn expanded my view of what it means to be human and to live in a human body.

I was told early in my training to expect about a third of my patients to die. I am not sure if the number is accurate (published estimates range from 10 percent to 30 percent), but I have cared for scores of patients in their final days and hours. And some of the sickest patients, whom I’ve been certain would die, have survived. The profound uncertainty of our patients’ trajectories can lead to all kinds of emotions. I have been cynical and closed-off. I have been deeply attached and overwhelmed with grief. I have wondered if what I do is worth it—for my patients and for myself. I have had to find a way to be in the present with my patients and to separate the meaning of my work from whether my patients survive.

My friend and mentor, Rana Awdish, a pulmonary and critical care physician in Michigan, wrote of her experience in the pandemic: “When we couldn’t stop the surge, when the scale of the loss exceeded our ability to comprehend it and we couldn’t see a way out, we had to find another way. By adjusting our scope and refocusing on the individual patient who lay before us, we were reminded of what we knew: Each patient held an endless world within them. And though we couldn’t save the world, we could deliberately hold the sacredness of a single, irreplaceable life in our field of view.”

I think of infant Finn and remind myself that each life is precious just as it is. While we certainly hope that our patients will go on to do things they find pleasure and meaning in, that is not why we care for them. Rather, we care for our patients because they are human beings and they deserve care. Focusing on that, even in the darkest moments, gives me hope for the patient before me and for our collective future.

More from The Nation

Texas Is “Hell-Bent” on Preventing Pregnant Patients From Getting Life-Saving Abortion Care Texas Is “Hell-Bent” on Preventing Pregnant Patients From Getting Life-Saving Abortion Care

Hours after a Texas judge ruled in favor of expanding abortion access to patients facing life-threatening complications, the state appealed the decision, blocking it from taking e...

These New Alzheimer’s Drugs Are a Travesty These New Alzheimer’s Drugs Are a Travesty

They cost a ton, have major side effects, and there’s deep skepticism that they even work. So why are we pushing them on patients?

The Private Equity Takeover of Hospice Care The Private Equity Takeover of Hospice Care

Half of all Americans now die in hospice care.

Witnessing the Pandemic From the Front Lines at New York City’s Oldest Public Hospital Witnessing the Pandemic From the Front Lines at New York City’s Oldest Public Hospital

Even as we work to treat the sick and prevent Covid’s further spread, we must also remember the dead.