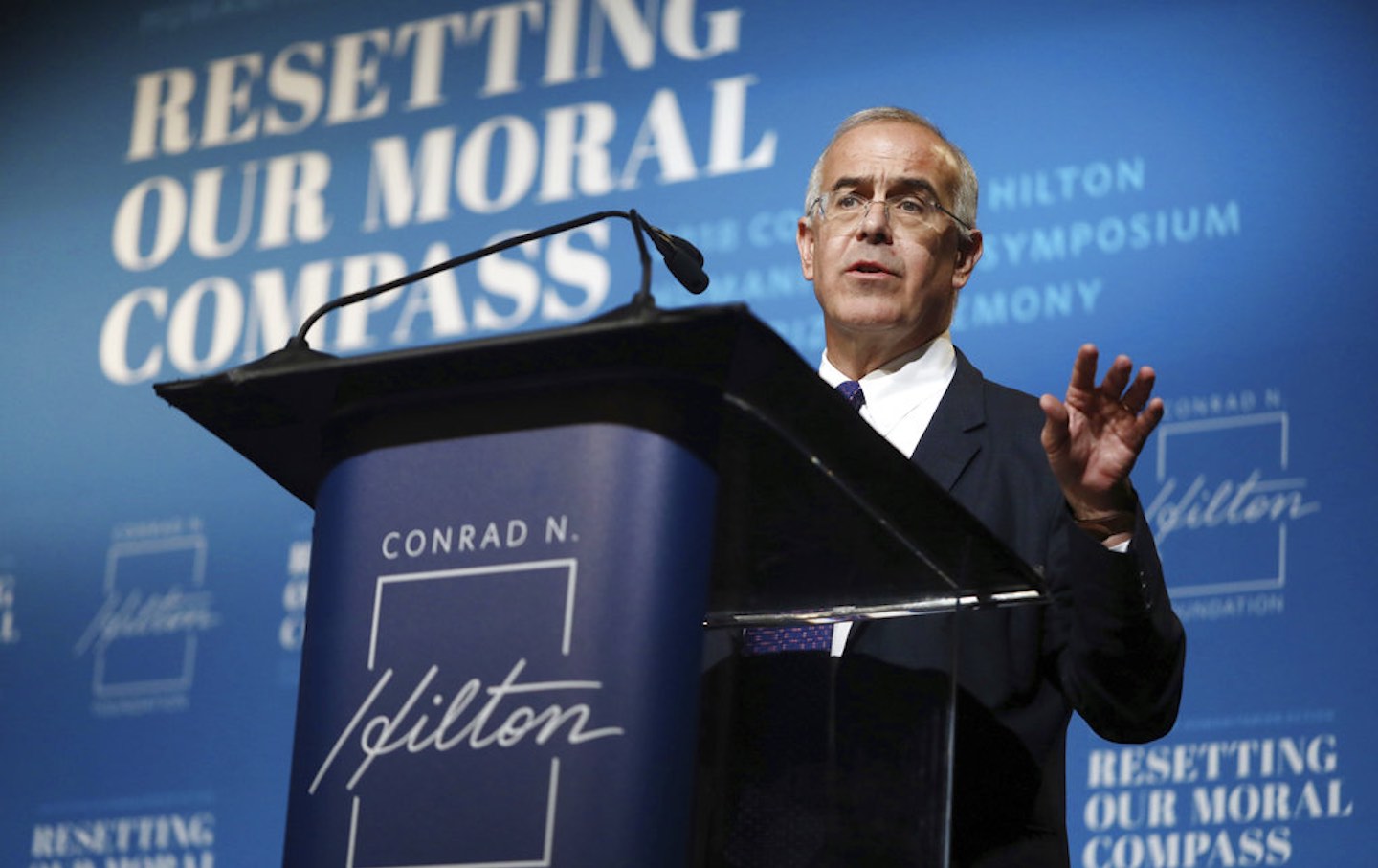

The Patronizing Moralism of David Brooks

In a series of recent essays, the New York Times columnist has pronounced all social ills the result of deficient moral fiber among individuals.

Take heed, American reprobates! Your self-appointed spiritual doctor, David Brooks, is diagnosing your faults, sins, and self-serving moral evasions, and his findings are grim. In successive turns at the bully pulpits of The New York Times and The Atlantic, Brooks has detected a collective failure to grow up and lay aside the childish things that haunt our epoch: self-absorption, incivility, tribalism, and other just plain rude repudiations of character and virtue.

Deprecated: Non-static method Athletics\TheNation\ACFBlocks::parse_popular_posts() should not be called statically in /code/wp-content/themes/thenation-2023/inc/single_article_functions.php on line 566

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

This line of argument has been a recurring theme in Brooks’s never-ending tenure as a commentator of mysteriously high profile. In 2011, he composed a didactic novel, The Social Animal, in a misguided effort to disguise his hortative program of national self-reform as literary entertainment. In 2017, he crafted an entire column in the form of the “Giving Pledge”— a vanity conceit launched by Warren Buffet in which billionaires flattered themselves by expounding on all sorts of good their money would do through charitable donations. Brooks’s version laid out a creepily expansive program for national moral greatness—only hypothetically, praise God, since he didn’t actually have the cash. Still, high on the heady convergence of world-conquering largesse and elite-bred moral certainty, Brooks set about assembling a Mad Libs–style vision of how reawakened virtue would once more bestride the American public: “poor kids,” “young adults” in the throes of a “Telos crisis,” “successful people between thirty-six and forty” would heroically “nurture deep friendships” while coming to learn “the habits of citizenship” and “possess the true spiritual north that orients a life.” As Jason Linkins observed in The Baffler, Brooks’s “proposal to launch a renewal of affective civic solidarity on the scale of a Google moonshot is a simple, self-contradictory means-and-ends misfire. It’s a bit like seeing Alexis de Tocqueville competing on Dancing with the Stars—or The Apprentice.”

Like many other elite pundits who profess to be chastened by the rude arrival of Trumpism on the national scene, Brooks has spent the past half-decade frantically retooling his brand identity. Fortunately, this hasn’t entailed all that much actual rethinking of anything; it’s chiefly been an exercise in repackaging his great rolling program of character reform as a tailor-made remedy for the gnawing civic malaise of the Trump era.

Hence his present stentorian sermons on our misbegotten national character. We can only face down the raging pathologies of a country that’s both desperately “sad” and “mean” by owning up to our own moral failures, Brooks warns. His Atlantic broadside, ruefully titled “How America Got Mean,” does include a quick disclaimer that ”economic inequality is real, but it doesn’t fully explain this level of social and emotional breakdown.” Instead, to get to the heart of the problem, we must cast a cold eye on our collective moral plight: “In a healthy society, a web of institutions—families, schools, religious groups, community organizations, and workplaces—helps form people into kind and responsible citizens, the sort of people who show up for one another. We live in a society that’s terrible at moral formation.”

To lay out the scale of the moral reclamation job ahead, Brooks supplies a pundit’s tour d’horizon of Western self-reform and moral instruction, invoking the German Bildung tradition, the scattered pedagogical wisdom of John Dewey and Walter Lippmann, a smattering of social-scientific research into the roots of the meanness plague, and the work of a clutch of latter-day sociological students of the culture wars such as James Davison Hunter and Jonathan Haidt. The breakdown of our former frameworks of moral inquiry, as Brooks charts them, culminates in a full-scale crisis of purpose, leaving rampaging anomie in its wake. His diagnosis could double as the plot synopsis of a Chuck Pahluniak novel:

Sadness, loneliness, and self-harm turn into bitterness. Social pain is ultimately a response to a sense of rejection—of being invisible, unheard, disrespected, victimized. When people feel that their identity is unrecognized, the experience registers as an injustice—because it is. People who have been treated unjustly often lash out and seek ways to humiliate those who they believe have humiliated them.

Armed with this battery of hurt feelings and stifled recognition, the confused and bitter American public seeks misguided solace in politics, mistaking the brittle tribalism of political belonging for the stuff of restorative moral communion.

For people who feel disrespected, unseen, and alone, politics is a seductive form of social therapy. It offers them a comprehensible moral landscape: The line between good and evil runs not down the middle of every human heart but between groups. Life is a struggle between us, the forces of good, and them, the forces of evil.

It is true in many ways that America’s social fabric is fraying into a state of moral incoherence, as any glance at our bathetically Hobbesian political order or a tour through social media will quickly confirm. It’s also true that a therapeutic ethic of self-fulfillment at all costs—together with the trauma-driven rhetoric that often accompanies it—produces no end of frustratingly involuted public discourse and institutional enclosures of our emotional life. But what’s striking in Brooks’s longsome indictment of American meanness is that he never once names the atomizing, divisive, and solidarity-leaching logic of our capitalist political economy as the force that unleashes and strategically enforces this wide array of morality-shunning character deformations.

Indeed, Brooks goes out of his way to exempt any straightforward acknowledgment of the ugly legacies of possessive individualism in American life, in typically overstrained Brooksian rhetoric. On the one hand, he glumly concedes that

in our society, the commercial or utilitarian goals tend to eclipse the moral goals. Doctors are pressured by hospital administrators to rush through patients so they can charge more fees. Journalists are incentivized to write stories that confirm reader prejudices in order to climb the most-read lists. Whole companies slip into an optimization mindset, in which everything is done to increase output and efficiency.

But this, happily, isn’t a structural feature dictating how work is organized and rewards administered under the civic anomie of American capitalism; no, it’s just another regrettable category error, akin to that committed by the hurt, aggrieved souls seeking a deliverance in politics that politics can never supply. In this case, too, a more robust brand of moral axiom will pretty much sort things out: “Moral renewal won’t come until we have leaders who are explicit, loud, and credible about both sets of goals. Here’s how we’re growing financially, but also Here’s how we’re learning to treat one another with consideration and respect; here’s how we’re going to forgo some financial returns in order to better serve our higher mission.”

As Brooks casts about for a real-world example of this sort of character-forming phronesis in the world of enterprise, he settles on one that speaks volumes about both his own social vision and the discursive preferences of his Atlantic readership. Just as Ben Franklin served as the ideal-type for Max Weber’s interpretation of the spirit of capitalism, so has Brooks divined the path back to American civic virtue in the person of… Jim Lehrer, whom he was fortunate to work with “early in my career, as a TV pundit.” “Every day,” Brooks writes,

with a series of small gestures, he signaled what kind of behavior was valued there and what kind of behavior was unacceptable. In this subtle way, he established a set of norms and practices that still lives on. He and others built a thick and coherent moral ecology, and its way of being was internalized by most of the people who have worked there.

This is the whole problem with David Brooks’s program of moral reform: You start off in search of the wayward spirit of American civic renewal, and you find yourself back in a pundit’s green room. At this point in “How America Got Mean,” you realize the essay would have been better titled, “Lament for the Moral Ecology of the American Elites.” What Brooks is prescribing as the all-purpose moral fixative for the polycrisis of America in the Trump age is actually a case study in what Christopher Lasch, writing of Teddy Roosevelt’s own robust (and dementedly imperialist) program of national renewal in the early 20th century, called “the moral and intellectual rehabilitation of the ruling class.” In this regard, Brooks’s essay is a marquee manifesto for The Atlantic, a publication that has devoted itself to the many baroque forms of Brahmin status insecurity since its founding, and now functions chiefly as its own therapeutic DSM manual for the thwarted neoliberal identity and its own rites of tribal belonging in the age of Trump.

Brooks does alight on one crucial counterexample to the baleful drift of political activism into tribalist social therapy. The organizing principles of the civil rights movement, he notes, should serve as a chastening rebuke to the amoral chaos of today’s political scene. “At their best, the civil-rights marchers in this prophetic tradition understood that they could become corrupted even while serving a noble cause,” he writes. “They could become self-righteous because their cause was just, hardened by hatred of their opponents, prideful as they asserted power. King’s strategy of nonviolence was an effort simultaneously to expose the sins of their oppressors and to restrain the sinful tendencies inherent in themselves.”

This effort to wrest a redemptive moral lesson from the fallen world of politics, like many similar flourishes from Pastor Brooks, teems with sobering and instructive ironies for long-suffering readers of his work. In reality, Brooks has used his perch at the Times op-ed shop to issue crude partisan glosses on the history of the civil rights movement so as to stoke entirely phony moral equivalencies between a runaway cancel culture in American universities and the rise of a “white identitarian” movement on the right. In the course of trying to lend a veneer of legitimacy to this howler, Brooks also appropriated a favored talking point of right-wing zealots keen to demonstrate that liberals are the real racists—a claim that “a greater percentage of congressional Republicans voted for the Civil Rights Act than Democrats.” Of course, Brooks uses a percentage comparison here for the simple reason that the GOP caucus in the Great Society Congresses was vanishingly small, and thus not particularly promising fodder for sweeping partisan generalizations.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

What’s more, of course, the most decisive factor in that 1965 vote was geographic rather than partisan, as data journalist Harry J. Enten explains: “it becomes clear that Democrats in the north and the south were more likely to vote for the bill than Republicans from the north and south, respectively. It just so happened southerners made up a larger percentage of the Democratic than Republican caucus, which created the initial impression that Republicans were more in favor of the act.” Brooks’s concerted whitewashing of this history, together with his ham-handed bid to blame a half century of conservative-bred white backlash on a handful of campus administrators and activists, is both a textbook study in the sort of “tribal” distortion of forthright civic and moral inquiry that he decries at such length here, and an equally damning instance of the rabid pursuit of extra-empirical schemes of meaning under the banner of partisan in-group affiliation. You might even go so far as to call it, I dunno, mean.

I should make clear that I mention Christopher Lasch advisedly in this context; Brooks’s recent New York Times outburst—titled, of course, “Grow Up, America”—repeatedly cites Lasch’s best known work, the 1979 jeremiad The Culture of Narcissism. Lasch, as it happens, was my adviser in graduate school, and it’s been a grim intellectual crucible for me to see his work cited admiringly—and in predictably bowdlerized, stunted, and distorted fashion—on the American right. In his invocations of The Culture of Narcissism, Brooks carries on this appalling annexation project—and does so by once again excising all of the book’s many discussions of the central role that the capitalist political economy plays in the rise of a collective American narcissistic personality. Brooks approvingly quotes Lasch’s diagnosis of a debilitating brand of narcissism that leaves its sufferer doomed to seek “neither individual self-aggrandizement nor spiritual transcendence but peace of mind, under conditions that increasingly militate against it,” while of course neglecting entirely to note Lasch’s own characterization of those conditions.

The professionalized therapeutic ethos that helped spawn the culture of narcissism, Lasch wrote near the book’s end, accompanied “the transition from competitive capitalism to monopoly capitalism.… [T]he medical and psychological assault on the family as a technologically backward sector went hand in hand with the advertising industry’s drive to convince people that store-bought goods are superior to homemade goods. Both the growth of management and the proliferation of professions represent new forms of capitalist control, which first established themselves in the factory and then spread throughout society.”

Lasch would later relinquish the orthodox Marxist rhetoric of this analysis, but it remained substantively unchanged throughout his work. To interpret the plague of narcissism in American culture as something essentially rooted in a lapse of personal and spiritual discipline, as Brooks and countless other right-wing thinkers have done in Lasch’s wake, is much like attributing climate change to the phases of the moon. Narcissism is a symptom, rather than a cause, of a much more far-ranging moral squalor, unambiguously bred and sustained by the political economy of American capitalism. In other words: Grow up, David Brooks.