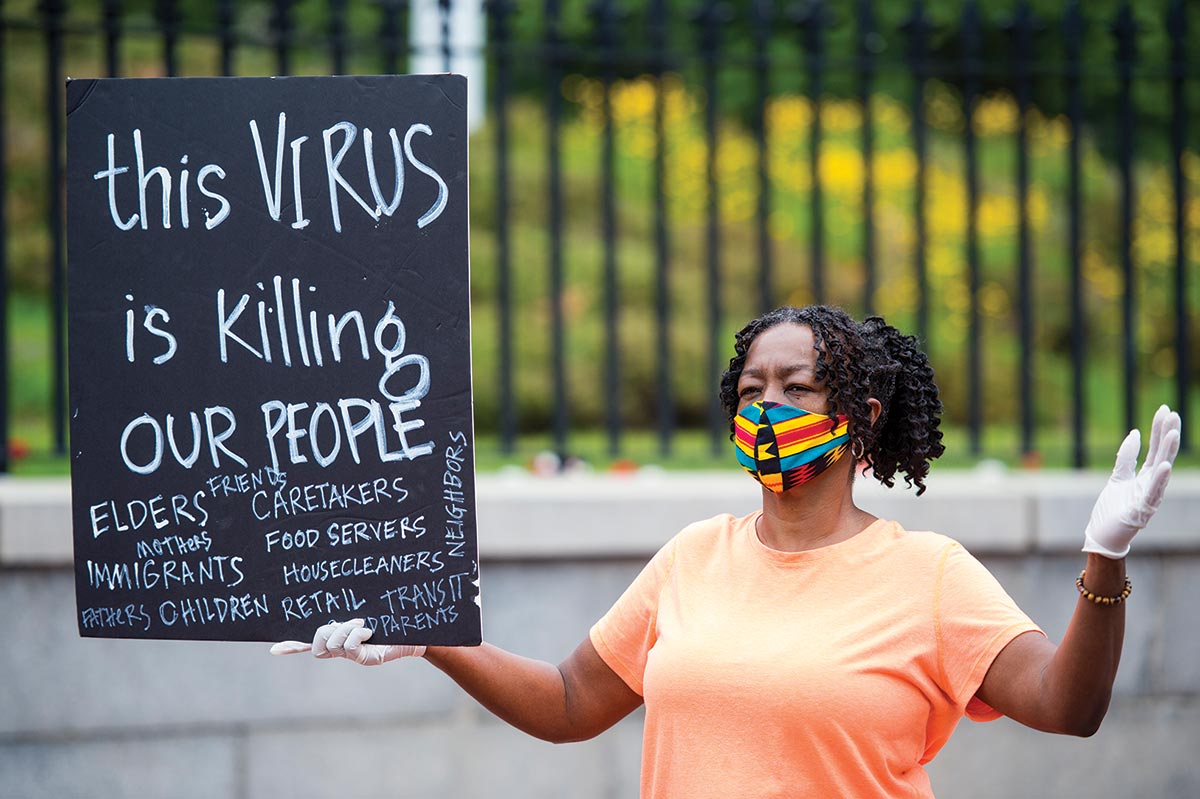

As of the first week of August, there have been at least 160,000 deaths in the United States from Covid-19. There is data indicating race and ethnicity for approximately 90 percent of these deaths; in age-adjusted numbers analyzed by the American Public Media Research Lab, the widest disparities afflicted Black, Indigenous, Pacific Islander, and Latinx populations. Black mortality rates range from more than twice to almost four times as high as for white people. Among Indigenous people, the rates are as much as three and a half times as high and are two times as high for Latinx people. The death rate for predominantly Black counties is six times that of predominantly white ones.

It is telling that all racial groups marked as minorities in the United States, including Asians and Pacific Islanders, are more likely than whites to die from Covid. And the true picture may be much worse. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention weights its calculations in ways that omit areas that have few to zero deaths—which, coincidentally, happen to be largely white. According to an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association, this weighted counting “understates COVID-19 mortality among Black, Latinx, and Asian individuals and overstates the burden among White individuals.”

On the basis of these statistics, a federal committee advising the CDC is reportedly considering who should be put at the head of the line upon the release of a vaccine. There is relatively little disagreement that “vital medical and national security officials” (as they were described in a recent New York Times article) would be first, as well as others considered essential workers—however unclearly that’s defined. (Teachers? Poll workers? Grocery store clerks? Housekeepers? Mortuary staffers? Bus drivers?)

More contentious is whether especially vulnerable populations should be fast-tracked—and in particular whether those identified as Black or Latinx should be prioritized. The controversy centers on the use of race and ethnicity as proxies for all the prejudices and vexed social conditions that render raced bodies as more susceptible to begin with. One may wonder, in other words, why minorities’ disproportionately lower survival rates couldn’t be more accurately attributed to homelessness or dense housing or lack of health insurance or inadequate food supplies or environmental toxins or the ratio of acute care facilities to numbers of residents in the ghettoized locations that have become such petri dishes of contagion.

This is not to suggest that the discrimination suffered by Black and Latinx people is simply about class. In a nation shadowed by eugenic intuitions, race is its own risk. American prejudices about color and race are rooted in powerful long-term traditions of anti-miscegenation and untouchability. The propinquity of dark bodies—sometimes merely eye contact—incites anxiety and a fear of social contamination that operates a bit like the bestowing of “cooties” among children. Even to doctors, color can be an unacknowledged source of revulsion if they have grown up in all-white environments; it can operate affectively and aversively, like stigmatizing witchery. One can understand why racially prioritized vaccinations may be attractive to some as an attempted reversal of that acculturated sorcery and its death-enhancing consequence.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

There are surely no easy answers to managing scarce resources when dealing with a disease whose tragic boundlessness is still revealing itself. Regardless, I am convinced it will not end well to build public health architectures that use race or ethnicity to signify innate vulnerability—or, for that matter, invulnerability. There is already global panic about which of us will live or die. One might anticipate vaccine eligibility by race turning into an unseemly competition over blood. How, precisely, would race or ethnicity even be determined? By how you look? Who you grew up with? Your name? Your neighborhood? Would the whole thing end up being an economic boondoggle for sketchy DNA testing companies?

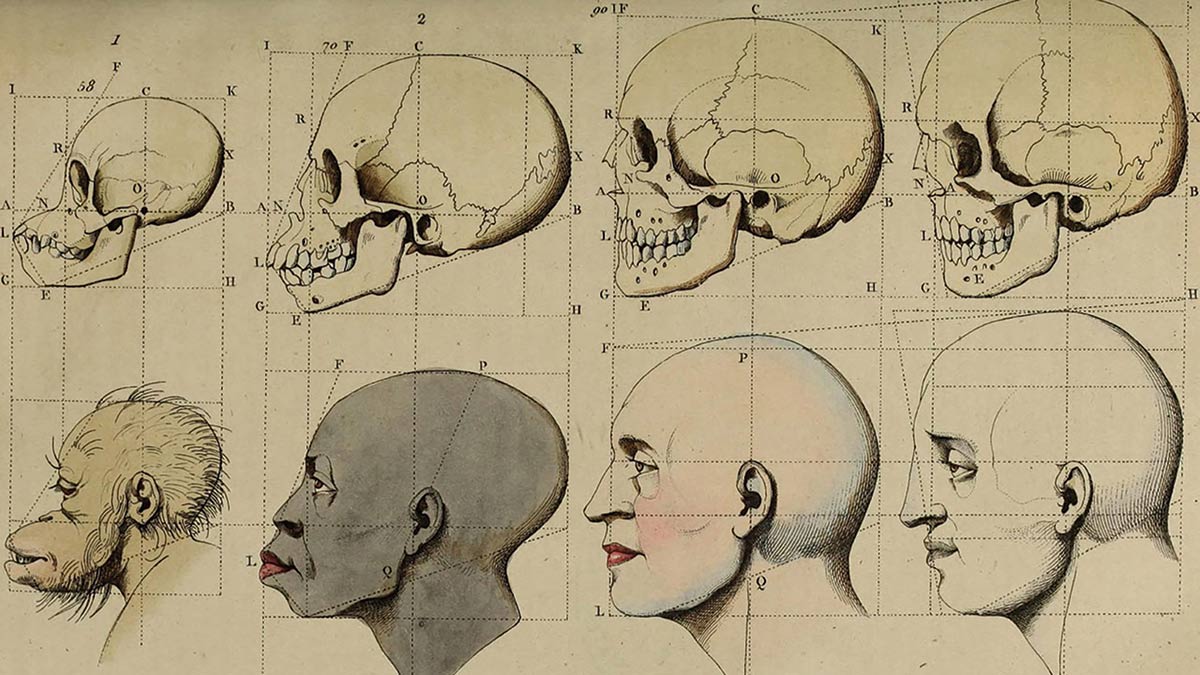

There are so many absurd assumptions about embodied racial difference abroad in our land. “They” can’t swim because their bodies don’t float. “They” can jump higher, thanks to an extra muscle in their legs. The imagined Black body has a smaller brain, a bigger butt, a longer penis, saltier blood, wider feet, thicker skin, extra genes for aggression. Nor is this just ancient history. To this day, the spirometer, a machine to assess breathing function in asthma treatment, uses different scorings for black and white patients, based on a more than 200-year-old assumption that slaves had a biologically unique lung volume.

Even now, American medical students are taught that Black people have greater muscle mass than whites. This is a fiction that dates to the days of slavery, yet it informs how kidney disease is treated today, for creatinine levels are used to measure kidney function, and greater muscularity can increase the release of creatinine in blood. But rather than assess individual patients’ muscle mass, most hospitals rely on an algorithm that automatically lowers Black patients’ scores below the level measured—thus delaying treatment in some instances by making all Black people appear healthier than they might be.

A test developed and endorsed by the American Heart Association weighs race in determining the risk of heart failure. The algorithm automatically assigns three extra points to any “nonblack” patient; the higher the score, the greater the likelihood of being referred to a cardiology unit. Yet there is no rationale for making race a lesser risk factor for heart disease in some people, and the AHA provides none. Needless to say, Black and Latinx patients with the same symptoms as their white counterparts end up being referred for specialized care much less often.

Many dangerously unscientific beliefs about racial difference are baked into present-day pharmaceutical titrations and point-based algorithmic calculations, altering the diagnosis of everything from the incidence of skin cancer to diabetes to the likelihood of developing osteoporosis to tolerance for pain. Underserviced, too many Black patients go unnoticed till they’re at death’s door with “sudden” or “aggressive” versions of common diseases. With endless irony, that is when those neglected bodies may become the exception that proves the rule of “genetic difference.” Medical historians like Harriet Washington, Dorothy Roberts, Lundy Braun, Troy Duster, and Evelynn Hammonds have been complaining about such stereotypes and biases for decades, but perhaps it has taken the convergence of Black Lives Matter, a global health crisis, and a diverse new generation of outspoken medical professionals for this topic to finally be taken seriously.

I raise these stereotypes in order to consider the medical consequences of such epistemic foolishness, particularly at a moment when Covid-19’s disparate toll on Black and brown bodies has directed attention to underlying conditions. Careful observers will point out that underlying conditions are not the same as innate predisposition: There is no known human immunity to this coronavirus. Our universal susceptibility to it is underscored by the virus being labeled “novel.” But it bears repeating that underlying conditions like stress, age, diabetes, asthma, crowded living conditions, and having a risky job are factors directly accounting for greater rates of infection. This much is not a mystery.

Attention to the fate of people of color, in particular, is both overdue and double-edged: It highlights inequities but also risks reinforcing them as somehow innate. If the US rates of infection are wildly off the charts compared with other nations’, we do not generally blame it on the innate or underlying conditions of a peculiarly American biology; we know these numbers are the product of poor policy decisions. Just so, disproportionate deaths in communities of color must not be attributed to an imagined separateness of Black or Latinx biology. Yet that is the risk when, as just one example, half of white American medical students believe in medical myths about race.

Amid a welter of misguided fantasies, we forget at our peril that the traumas and social factors disproportionately affecting people of color are also driving death rates among whites, even if not to the same degree. Trap white people in crowded, poisoned contexts devoid of public assistance, and they die too.

The proposal to use race or ethnicity as a marker of vulnerability to Covid-19 does one kind of work in the context of vaccine prioritization. But how it might intersect with the procedures that govern triage in hospital settings is not yet known. Recognizing the risks of bias in such emergency circumstances, the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office for Civil Rights issued a bulletin on March 28 restating a federal commitment to protecting “the equal dignity of every human life from ruthless utilitarianism.” Under the Americans With Disabilities Act and the Affordable Care Act, people “should not be denied medical care on the basis of stereotypes, assessments of quality of life, or judgments about a person’s relative ‘worth’ based on the presence or absence of disabilities or age.”

Discrimination against those with loosely defined disabilities is quite common. The University of Washington Medical Center, for example, has argued for “weighing the survival of young otherwise healthy patients more heavily than that of older, chronically debilitated patients.” The reconfigured overlay of race as a debilitating, resource-consuming morbidity risk worsens the situation. Disability rights advocates have been working hard to push these concerns to the front burner, urging Congress to ban triage based on “anticipated or demonstrated resource-intensity needs, the relative survival probabilities of patients deemed likely to benefit from medical treatment, and assessments of pre- or post-treatment quality of life.” On July 22, the advocacy organization Disability Rights Texas filed a complaint with the Department of Health and Human Services against the North Central Texas Trauma Regional Advisory Council for its use of a rigid, point-based, algorithmic scoring system that can automatically exclude from intensive care people with a range of preexisting conditions and disabilities without resort to an individual assessment. Other states have begun to reexamine their crisis rules in response to such concerns.

Perceptions of disease and deviance and feelings of disgust have always enabled the timeworn constructions of embodied difference to be carried forward. When Donald Trump speaks of “the China virus,” he not only gives the disease a race and a place; true to his outsize colonial imagination, he gives it distance. It’s over there, not here, well removed from the conceptual possibility of our susceptibility. If we are afflicted, it is not just the illness that debilitates us but our anger that we have been invaded by “them.”

It is this form of displaced animus that emerged in spikes of anti-Asian prejudice that arose in the wake of outbreaks of smallpox in San Francisco. The epidemic was blamed on the residents and culture of Chinatown in the 1800s, a pattern that culminated in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Anti-Semitic nativism targeted Jews after bouts of typhus in 1892. Mary Mallon, better known as Typhoid Mary, was an asymptomatic carrier of typhoid fever; her arrest in 1907 on public health charges galvanized anti-Irish sentiment in New York City, depicting them as immigrants importing unsanitary and slovenly habits. When the AIDS epidemic started in the 1980s in the United States, some people told themselves it was a disease conveniently localized to the bodies of gay men. And when the Zika virus was carried from equatorial regions by mosquitoes riding the waves of climate change, New York City health officials began spraying insecticides by zip code (focusing on neighborhoods like East Flatbush, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, and Brownsville in Brooklyn, as well as the neighborhood in upper Manhattan once known as Spanish Harlem), as though those pesky, identity-politicking insects could simply be redlined.

Instead of coming together around our shared vulnerability, time and again we have created a set of golems to stand in for the virus, divisive demons that direct our fears of inherent virulence, murderous voraciousness, and leechlike parasitism. Asians. Aliens. Anarchists. Reporters. Media. Social media. Dr. Anthony Fauci. California. Chicago. “That woman” who is the governor of Michigan. People who wear masks. People who don’t wear masks. It is not by accident that Trump’s targeted rhetoric to white suburban housewives so neatly suture race, riot, and disease as a way to channel the existential fear to which we are all so vulnerable right now: If you can keep “them” out of your neighborhood, everything is going to be all right.

Americans are not raised to believe in the entanglements of a common fate. The very notion of public health has been undermined by ingrained brands of individualism so radical that even contagious disease is officially regulated by the vocabulary of “choice,” “freedom,” and “personal responsibility.” Many of us live in bubbles of belief that conceptual walls will protect us from things that are not easily walled off: Guns will bring peace, housing discrimination will bring bliss to soccer moms, segregated schools will serve up stable geniuses, and owning an island in the Caribbean will seal us off from child molesters, Mafia dons, and domestic abuse.

These comforting bromides are akin to naive beliefs that disease invariably marks people’s bodies in visible ways. “Surely we’ll be able to see it coming.” “You’re fine if don’t have a fever.” “You can’t spread it if you’re not coughing.” “You won’t give it to anyone if you’re asymptomatic.” Well before this pandemic hit, we Americans were blinded by the walls of our private bunkers. Yet the sense of entitlement that supposes disaster will strike over there but not in my backyard guarantees an amplification of misdirected resources and relative disparities from which everyone will suffer eventually.

I don’t have an answer for any of this, although I truly wish I could think my way to a happy ending. So I read and study and reread those statistics about how ethnic minorities, Black people, Black women are dying at higher rates. I am not an epidemiological statistic, yet I have no doubt that my body will be read against that set of abstracted data points. I—and we all—will be read as the lowest common denominator of our risk profiles at this particular moment. Not only are we no longer a “we,” but I am also no longer an “I” in the time of the coronavirus.

Meanwhile, Covid-19 makes snacks of us. The fact that there may be variations in death rates based on age or exposure or preexisting immunological compromise should not obscure the epidemiological bottom line of its lethality. Covid-19 kills infants; it kills teenagers; it kills centenarians. It kills rich and poor, Black and white, overworked doctors and buff triathletes, police and prisoners, fathers and mothers, Democrats and Republicans. We can divide ourselves up into races and castes and neighborhoods and nations all we like, but to the virus—if not, alas, to us—we are one glorious, shimmering, and singular species.