Through most of human history, opium circulated in very small quantities and was used primarily as a medicine. Anatolia was probably the region in which farmers first began to cultivate poppies as an important commercial crop, and the practice is thought to have spread outwards from there. The armies of Alexander the Great are believed to have carried opium into Iran, hence the derivation of the Persian and Arabic words for opium, “afyun,” from the Greek “opion.” The Perso-Arabic terms, in turn, engendered the word “afeem,” widely used across the Indian subcontinent, and Chinese terms “afyon” and “yapian.”

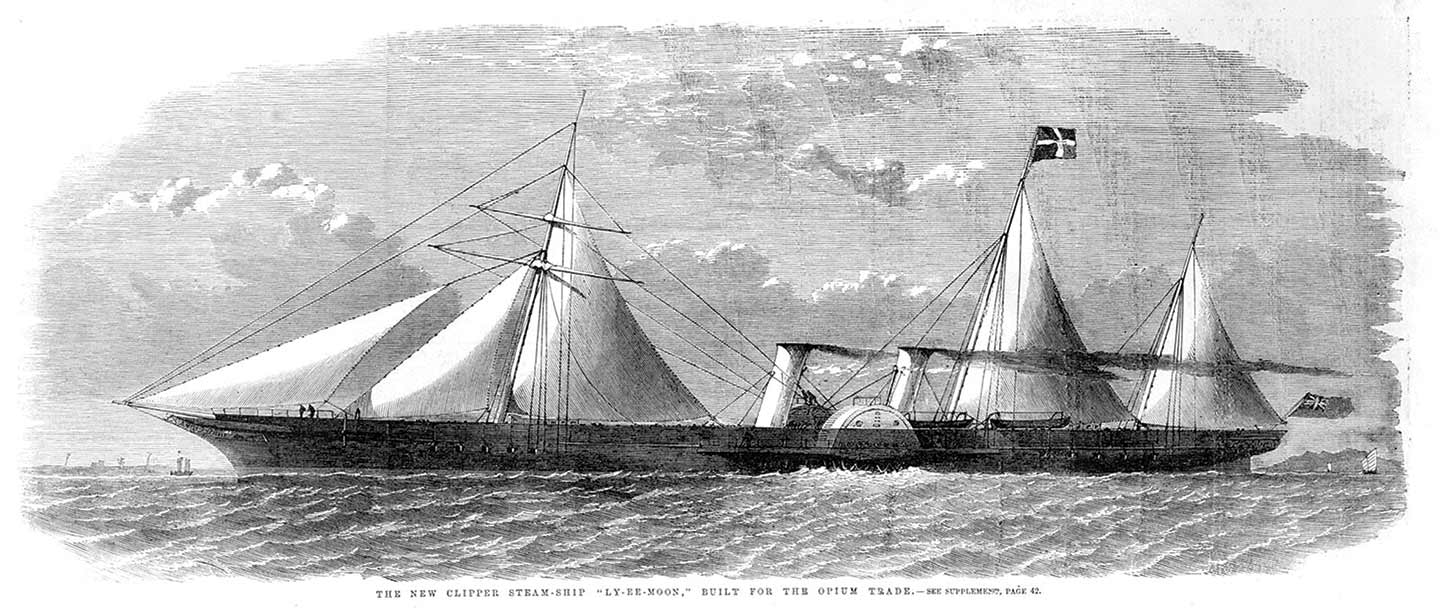

A useful analogy in thinking of the social history of opium is that of an opportunistic pathogen, one that goes through long periods of dormancy, affecting very small numbers of people. But when social processes and historical events provide the pathogen with an opportunity, it bursts out to rapidly expand its circulation. With opium this happened in several phases, over centuries, usually in connection with empires. The Mongol Empire, for instance, along with its successor states, played an important role in propagating opium in many parts of Asia in the 15th and 16th centuries. This came about because opium was adopted as a recreational drug by imperial courts and ruling elites; it was not used as an instrument of state policy. The pioneer in that regard was the Dutch East India Company, which made extensive use of opium in its quest for commercial and territorial expansion in Southeast Asia. Yet while the Dutch led the way in enmeshing opium with European colonialism, it was the British in India who perfected the model of the colonial narco-state, when they began to use opium to pay for their imports of Chinese tea, a commodity that produced enormous revenues for Britain in the colonies as well as the metropolis.

After Britain, the country that benefited the most from the China trade—and, therefore, the global traffic in opium—was none other than the United States. And in the United States, unlike in Britain, it is well-established that the beneficiaries included many of the preeminent families, institutions, and individuals in the land.

This is not to imply that fewer British subjects benefited from opium; quite the contrary. Since Britain was the prime mover behind the global drug traffic, its involvement with opium was obviously on a much larger scale than that of the United States. Not only was the British colonial apparatus in India overseeing the production and distribution of most of the world’s opium, but Britain was also home to the single largest, and richest, group of “private traders” involved in smuggling opium into China. It is possible that the pathways of the fortunes that British traders brought back could be tracked in the same way the circulation of the wealth derived from slavery has been charted in recent years. But the task would not be an easy one, because opium money seeped so deeply into 19th-century Britain that it essentially became invisible through its ubiquity. In any event, this exercise has not been undertaken, possibly because of its inherent difficulties, or because it would threaten cherished myths about Britain’s imperial past, or because there exists no domestic constituency to press for such an investigation, as was done for slavery.

On the other hand, even though the United States’ involvement with the 19th-century opium trade was on a far smaller scale than that of Britain, what became of the money that was brought back by American private traders has been tracked in considerable detail. The principal reason for this is probably that those funds had a much greater impact in the young, newly independent country, because its economy was tiny compared with Britain’s.

Such was the influence of the China trade on the United States that its place in American memory is very different from that in British or Indian memory. One sign of this is that while Britain possesses vast collections of Chinese objects, books, and artworks, it does not, so far as I know, have any museums devoted solely to the China trade: Its Chinese artifacts are mostly housed in institutions that are global in scope, such as the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. In America, by contrast, there exists a museum dedicated entirely to the China trade. Nor is this the only one; there are several others in which the China trade figures prominently, such as the impressive and well-funded Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Mass.

Another measure of the impact of the China trade on the United States is the sheer number of American towns and cities named Canton: There are more than 30, twice as many as are named after London. Yet while there are many American Cantons, there is not a single Guangzhou or even Whampoa: Those names would perhaps have made China’s unseen presence within the country uncomfortably real. The word “Canton” thus served to create a very particular niche within American memory, one in which China was domesticated and anglicized and the disconcerting realities of the opium trade were rendered palatable.

Those realities have been the subject of several excellent studies, including John R. Haddad’s America’s First Adventure in China, Dael A. Norwood’s Trading Freedom, and Jacques M. Downs’s The Golden Ghetto: The American Commercial Community at Canton and the Shaping of American China Policy, 1784–1844. The last of these was the outcome of a lifetime’s work: Downs combed through the records of all the major traders, which together constitute an archive of monumental proportions, having been preserved by “New Englanders and Philadelphians—people who never discard anything, be it documents, clothes, broken furniture, or outworn institutions.” Yet, while massive in size, the archive does not necessarily provide a transparent window on the past: The traders were generally very careful to hide the real nature of their businesses, even warning their families back home not to make anything public of their letters. In some instances, the traders’ descendants selectively destroyed papers that mentioned the buying and selling of opium.

Opium did not, by any means, account for the entirety of the traders’ businesses, but their other ventures were entirely predicated on it. They used their earnings from the drug to fund their purchases of teas, porcelain, silk, artworks, and much else. Thus, for example, in a letter written shortly after Commissioner Lin Zexu shut down the opium trade in 1839, Robert Bennet Forbes, a young Yankee trader, explained that no other part of the foreign merchants’ business with China could function without it: “[T]he Opium trade being cut off there is no money… thus does the Opium Trade affect every one trading here and us too… we cannot get money to buy tea & so we do not get our commissions.”

Traders like Forbes and his brother John understood perfectly well, as Downs notes, that “the entire China trade, was based on the opium traffic.” It is essential to remember, therefore, that America’s China trade, as a legitimate commerce, existed for only about 20 years, from 1784 to 1804. When applied to later forms of the commerce, the expression “China trade” is nothing other than a polite euphemism, much like calling Pablo Escobar’s cocaine business the “Andean trade.”

The coupling of the United States and China is not a new phenomenon, as many American pundits seem to believe. As Norwood explains in Trading Freedom, this link has existed since the earliest days of the republic. In America, as in Britain, it was tea that created the initial connections. Americans too were enthusiastic drinkers of tea, which “had a special place in the new nation’s political imagination for its ties to the performance of gentility,” Norwood writes. But during the colonial period, Americans were expressly forbidden to trade with China, that being the exclusive prerogative of the East India Company. As a result, the tea that Americans drank had to be routed through Britain, which made it more expensive. The resentments generated by this exploded in 1773 with the Boston Tea Party, which helped light the fuse of the American War of Independence.

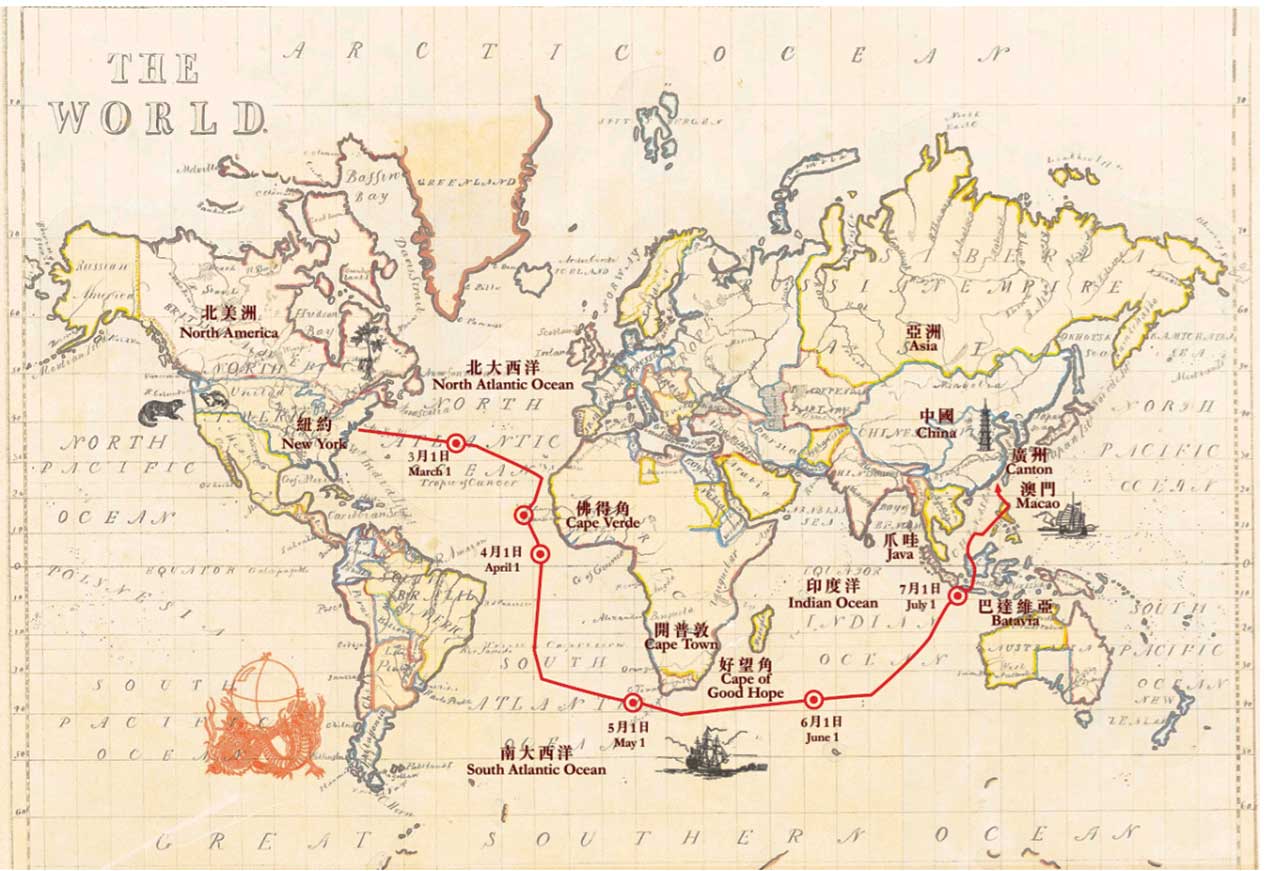

At the end of the war, in 1783, the new nation found itself independent but hemmed in. With nearby British colonies shut off from trade, China was one of the few worthwhile destinations open to American ships, a potential lifeline for the country’s merchants. “Send ships immediately to China,” John Adams told Congress in 1783. “This trade is as open to us, as to any nation.” Adams got his wish soon enough: The first American vessel to set off for China, a diminutive sloop by the name of the Harriet, hoisted sail the same year, within weeks of the departure of the British from New York. But the Harriet never reached China. Its cargo, which consisted mainly of ginseng roots, was acquired at an unusually high price by the captain of an East India Company ship at the Cape of Good Hope. This was probably done in the hope of dissuading the Americans from entering directly into the China trade—but the race was already on, and there was no stopping it.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The Harriet was followed, two months later, by a much larger vessel, whose mission was announced by its name: the Empress of China. The supercargo (business agent) was Samuel Shaw, a veteran of the Revolutionary War who would later become an ardent advocate for expanding America’s trade relations with China.

Six months after its departure from New York, the Empress became the first American ship to drop anchor at Whampoa, the last deepwater anchorage on the Pearl River. As Jonathan Goldstein relays in his study of Philadelphia and the China trade, the Americans were warmly welcomed by Chinese merchants, and the Empress’s cargo, which consisted of rum, furs, and “the largest quantity of ginseng ever brought to the Chinese market,” was sold for good prices. On its way back, the ship’s holds were filled with tea, porcelain, and textiles; it also carried some Shanghai roosters, which on being cross-bred with American strains produced a variety—the “Bucks County chicken”—that soon became immensely popular in the United States. These imports earned the Empress’s owners $30,000, a solid 25 percent return on their investment. Word of the ship’s successful voyage spread quickly along the Eastern Seaboard, and soon merchants and shipowners from Boston, Salem, Providence, New York, and Baltimore were also outfitting vessels for the journey to China. Within a few years of the Empress of China’s voyage, dozens of American ships were visiting Guangzhou annually.

But American merchants quickly ran into the same problem as others had before them: They had to pay for Chinese tea with Spanish silver dollars, and there was little the Chinese wanted from them other than bullion. Ginseng was one commodity for which there was some demand in China, but the American product was considered inferior, and there was only so much of it that the market could absorb. What else? For a while the answer was furs and sealskins, and that was how two Massachusetts families—the Delanos and the Perkinses—were drawn into the China trade along with John Jacob Astor, America’s most prominent vendor of furs. However, despite their initial success in selling furs to the Chinese, they soon encountered an insurmountable challenge: There were only so many seals and sea otters that could be killed before their numbers dwindled to a point where it was no longer economical to hunt them. Sandalwood became the next solution, and several Pacific islands were ransacked until they were thoroughly depleted of sandalwood trees; then it was the turn of the humble sea cucumber (bêche-de-mer)—and so on. All the while, there hung before the Americans the solution that had been fashioned by the British in the late 18th century: opium, a commodity that, unlike ginseng, did not obey the dictates of the supposed laws of supply and demand.

Americans were at a disadvantage, however, because in the early years of the opium traffic, they were shut out of the East India Company’s auctions in Calcutta. But the success of the British drug-running operation induced American merchants to look for other sources of opium, and they found a good one in Izmir (Smyrna), which was the outlet for Turkey’s principal opium-growing region in the interior.

The pioneers in the Turkish drug trade were the brothers James Smith Wilcocks and Benjamin Chew Wilcocks, from a prominent Philadelphia family. The Wilcocks brothers traveled as supercargoes on the first American ship to carry Turkish opium, the Pennsylvania, in 1805. The ship disposed of its 50 chests of Izmir opium even before reaching China; the cargo was sold in Jakarta. The success of this pioneering effort created something of an “opium rush” among leading American merchants like John Jacob Astor of New York, Joseph Peabody of Salem, and Stephen Girard of Philadelphia. Girard was a self-made man who had come to America from France as a cabin boy and had eventually become an immensely wealthy enslaver, banker, and shipping magnate. After learning of the Turkish opium route, he wrote urgently to his agents in the Mediterranean: “I am very much in favor of investing heavily in opium.” When Girard died in 1831, he was the wealthiest man in America, and is still counted among the richest Americans of all time; the same is true of Astor.

Soon there were so many American merchants in Izmir that they were able to monopolize the shipping of Turkish opium to China. But the output of the Turkish industry was not large, and the opportunities in India were simply too great to be missed. So even as they were setting up the traffic in Turkish opium, some Americans also began eyeing the East India Company’s auctions in Bengal. In 1804, Charles Cabot, captain of a Boston-owned ship, declared, “I intend to purchase Opium at the Company’s sales & proceed to the eastward where I have no doubt of being first at market.”

Those early attempts to tap the Indian market foundered initially because of the disruptions caused first by the Napoleonic Wars and then by the British-American War of 1812. But after that war ended in 1815, Americans began to expand their dealings in opium at a rapid rate. John Jacob Astor even sent a ship into the Persian Gulf in an attempt at finding another source to supplement the supplies from Turkey. Astor’s speculations in opium in this period were large enough to send tremors down his rivals’ spines. “We know of no one but Astor we fear,” declared the Boston firm that then dominated the Turkish market.

By 1818, Americans were, by some estimates, smuggling as much as a third of all the opium consumed in China, thereby posing a major challenge to the East India Company’s domination of the market. Indeed, competition from Americans, and their Turkish opium, was one of the reasons that the company ramped up its production in Bihar soon after.

Meanwhile, India continued to be by far the greatest source of profits in the opium trade, and American merchants remained eager to expand their reach into the Indian traffic: The fact that they were shut out of it only whetted their appetites. And it was not as if the Americans did not hold some winning cards of their own. Marketing Turkish opium in China had put them in a good position to act as agents for Indian businessmen; they knew the ins and outs of the trade and had acquired extensive contacts within smuggling networks. They also had their own receiving ships at Lintin Island, on the Pearl River, where they could offer to store their partners’ drug consignments at lower rates than those of the big British smuggling networks. Moreover, their connections with the business worlds of Bombay and Calcutta went back a long way, to the years immediately following the formal recognition of American independence in 1783.

By the late 1780s, several New England merchants had started to work with Parsi and Gujarati brokers in Bombay, because they offered better rates and more reliable service than English agents. Bombay’s major export then was cotton, while the American products that found a market there were gin, rum, iron, and cordage. At that time, British regulations made it difficult for Americans to carry Indian goods to China, but the rules changed after 1815, and that was when New England merchants plunged headlong into the trafficking of Malwa opium.

Soon, several American merchants, mainly from Salem, were residing in Bombay, where their provisions and housing were taken care of by their Parsi partners. While the Americans did find partners among the great Parsi merchant clans like the Wadia, Dadiseth, and Readymoney families, most of the bigger companies were already spoken for by the British behemoths like Jardine Matheson & Co. and Dent & Co. Thus, it was often the smaller Parsi firms that were more eager to work with them. Among the Gujarati firms that partnered with Americans, the most important was Ahmedabad’s Hutheesing Khushalchand, one of the largest Malwa opium brokerages.

The indefatigable Benjamin Chew Wilcocks of Philadelphia was one of the pioneers in establishing American-Indian partnerships in opium. By 1824, Wilcocks was doing business to the tune of 100,000 silver dollars annually with Hormuzjee Dorabjee of Bombay, and this kept growing steadily until his retirement in 1827, when he passed his company to a relative, John R. Latimer, who further developed the firm’s connection with Parsi merchants, most notably the Cowasjee, Framjee, and Hormuzjee families.

Following close on the heels of the Philadelphia merchants were the big opium-trading clans of Boston—the Perkins, Sturgis, Russell, and Forbes families, who were all as intricately interrelated as the Mafia lineages of southern Italy. They called themselves “the Boston Concern,” and the eventual merger of their firms would make them the single biggest opium trading network in China. The wealth they gained from the opium trade would establish them as core members of the elite circle that Oliver Wendell Holmes called “the Boston Brahmins,” America’s closest equivalent to an aristocracy.

“Almost without exception,” writes Downs, “Americans involved in opium during the last quarter century of the old China trade went home with fortunes after only a few years in the trade.”

Who were these fortunate Americans? It is no accident that their names read like a litany of the Northeastern upper crust: Astor, Cabot, Peabody, Brown, Archer, Hathaway, Webster, Delano, Coolidge, Forbes, Russell, Perkins, Bryant, and so on. They were mostly from the more privileged ranks of white settler society, families of British origin that had long been settled in the Northeast. Many of them were educated in elite schools like the Boston Latin School, Milton Academy, Phillips Academy Andover, Phillips Exeter Academy, and so on, and many went to universities like Harvard, Yale, the University of Pennsylvania, and Brown (named after a prominent slave- and opium-trading family from Providence).

To belong to an upper-crust Northeastern family in the early 19th century was different from being a member of other white elites, such as those in Europe or even the American South. The Northeastern elite was not principally a landowning group but a largely professional and mercantile class, subject to the fluctuations of a young and erratic economy. Businesses failed so frequently that even the most well-connected families lived with a certain degree of precarity.

A case in point is the family of Washington Irving, the author of “Rip Van Winkle,” “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” and other classic American stories. The writer and his brothers belonged to one of the most well-connected families of the Northeast, with a circle of friends whose surnames are now emblazoned on street signs across Manhattan and Brooklyn: Schermerhorn, Schuyler, Van Rensselaer, Livingston, and so on. Their family home was at 3 Bridge Street, a prize location in the heart of Lower Manhattan, and they also owned several country cottages between them. Yet it is clear from the family’s correspondence that the younger Irvings were constantly plagued by money worries. “I have a terrible load of debts on my shoulders,” complained Theodore Irving, one of the writer’s nephews, “which must be paid before I can breathe freely.”

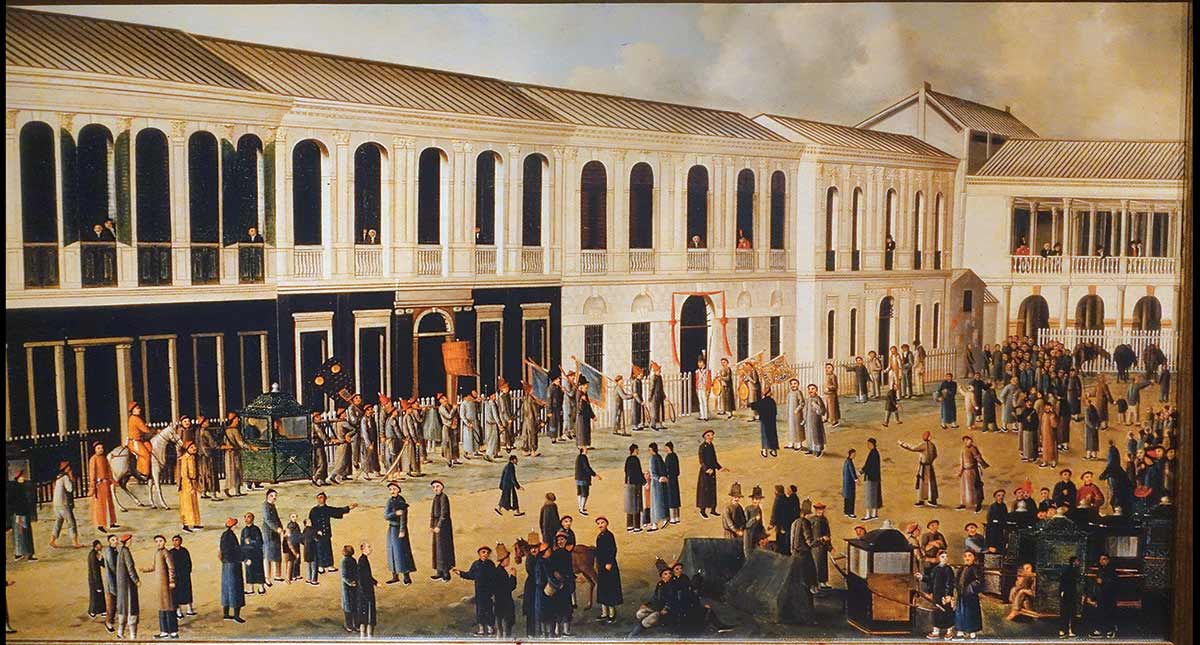

It wasn’t Theodore, however, but his younger brother William—Will to his relatives—who was chosen to go to Guangzhou to restore the family’s fortunes. Washington Irving himself pulled strings to get his nephew a clerkship in the biggest American opium-trading firm in China, Russell & Co. Twenty-two-year-old Will set off for China in 1833 with another young man of the same age, Abiel Abbot Low, who was also on his way to Guangzhou to join Russell & Co. Abbot Low, as he was generally known to his friends, was from a Salem family that had recently resettled in Brooklyn. He and Will became good friends during the journey, and on reaching Guangzhou they bought a boat together and would often go sailing on the Pearl River.

At around the same time as Irving and Low, another young American, by the name of Warren Delano Jr., also joined Russell & Co. All three men started off as clerks in the firm’s offices in Guangzhou’s Foreign Enclave, where Will was known to everyone as “a nephew of Washington Irving.” But while Low and Delano prospered, William Irving was not able to make much headway and began to despair of his prospects in the firm. His family did what they could to encourage him.

“I don’t like your being in low spirits,” wrote his brother Theodore, “you must cheer up—consider the few years to come as a Purgatory leading to ease and opulence—for be your prospects what they may in the [firm], you can certainly lay up something by speculating…. I would join you there tomorrow if money could be made—for alack a-day this poverty is a dirty thing.”

But Will’s gloom continued unabated, prompting his brother to write, reassuringly: “I have no wish that you should amass great wealth, my hope is that you may pick up some 20 or 40 thousand dollars, and be able to return to your native country while yet young—I would not have you pass more than ten years away.”

Yet even as Will was complaining about his own career, he was also reporting back on the vast sums that other Americans were making in Guangzhou. “We may have been mistaken,” wrote his father, “in the expectations of your soon getting an interest in the [firm], but from all we can learn from the frequent changes in the partners we still think your prospects are good. You say that Mr Heard leaves this spring having amassed $150,000 in three years.”

Will seems to have come to the conclusion that his inability to rise in Russell & Co. was due to the fact that, unlike Abbot Low and Warren Delano Jr., he had no funds of his own to speculate on opium. So he wrote to his relatives to raise money for him, which they very obligingly did, creating a small family fund in which Washington Irving, who appears to have been surprisingly well-informed about opium dealings in Canton, also invested. “[Y]ou will have great opportunities of speculating,” wrote brother Theodore, “Uncle Washington has commissioned father to advance monies, to allow you to speculate.” Despite this, advancement still eluded William, and he continued to flounder. Perhaps he found drug-trading distasteful; or perhaps he had no head for business; or perhaps his failure to get ahead was due to the fact that unlike Delano and Low, both of whom were from Massachusetts families, he had no close relatives in the Boston firms that were Russell & Co.’s closest partners. As a last resort, the Irving family placed their hopes for Will’s future in the hands of another well-connected American, Joseph Coolidge.

A Yankee blueblood and Harvard graduate, Coolidge was married to Thomas Jefferson’s favorite granddaughter, Ellen Wayles Randolph; Jefferson himself presided over the wedding at Monticello. A few years before his marriage, Coolidge had gone on a grand tour of Europe and, while passing through Paris, had sought out Washington Irving, who was there at the time. The writer took a shine to the young man and introduced him to Lord Byron, who was then living in Ravenna.

It was probably through Washington Irving that Coolidge found his way into the opium trade. The writer seems to have done him another good turn by recommending him to the Boston Concern, possibly in the hope that Coolidge would help young Will with his career. But this was a big mistake: Although charming and well-read, Coolidge was actually a quarrelsome and unreliable fellow who in the course of his short career in Guangzhou managed to antagonize almost everyone who crossed his path. Far from advancing Will’s career, Coolidge actually ended it, by starting a nasty quarrel. What the dispute was about is not known, but it was so ugly that Will left Guangzhou immediately, without even picking up his trunk or collecting his washing. His belongings were later forwarded to him in Manila by Abbot Low, who also disposed of the last of the opium that Will had bought with the funds his family had sent him. But that too did not turn out well, because the sale was made at a loss.

Thus ended the ill-starred venture of William Irving, who returned to New York with very little to show for his pains. He was one of the rare Americans of his class who failed to make a fortune in Guangzhou.

William Irving’s career may have diverged from the usual pattern, but he was entirely typical of American opium traffickers of this period in that he was a less affluent member of a privileged class. Many of the Yankees who established the American connection with China were, similarly, from the more penurious branches of the families of rich merchants. Usually they were the nephews of wealthy or influential men, and their entry into the business came about through nepotism, in the exact sense. This was true, for instance, of Samuel Russell, the founder of Russell & Co.: He started off in Middletown, Conn., as a “half-orphaned” white boy with only an “ordinary schooling.” But he had uncles in Providence who did business with China, and it was they who initially sent him out to Guangzhou and helped him establish his company. He could not have built his fortune without his family connections. That he was believed to be a “self-made man” is a sign of how the expression often conceals many kinds of privilege.

To go out to China at this time meant being away from one’s home for years on end, so young men needed to be very hungry and highly motivated to make the journey. It is not surprising, then, that many of those who went were the poor relations of rich men, boys who had grown up in the orbit of wealth, chafing at their own straitened circumstances and longing for an opportunity to better their lot. But to be merely intelligent, ambitious, and white wasn’t enough: A certain kind of class privilege was essential. To succeed in Guangzhou, a young American needed an education, as well as family connections to secure for him not just a clerkship in a good firm but also access to capital, which usually came, as in Will Irving’s case, from relatives. A penniless white boy from the backwoods, no matter how intelligent, hardworking, or ambitious, would have stood very little chance of finding a place at Russell & Co., let alone a Jew or a Black man.

Youth was another attribute that many American China merchants had in common, and sometimes it worked to their advantage, as it did for John Perkins Cushing, an impoverished nephew of Thomas Handasyd Perkins, one of Boston’s wealthiest merchants. Thomas H. Perkins had himself made an early journey to Guangzhou, as a supercargo on his brother-in-law’s ship, the Astrea, and had come back convinced that the future of American business lay in China. In 1803, he sent a couple of representatives to Guangzhou to set up an office; one was a senior partner and the other was Perkins’s 16-year-old nephew, John Cushing. The older man fell ill and died soon after reaching Guangzhou, and the inexperienced teenage boy suddenly found himself alone, saddled with a huge responsibility. Fortunately for him, the wealthiest and most powerful member of the Cohong syndicate took him under his wing. This was the immensely wealthy Wu Bingjian, a man of great intelligence and foresight. At the time of his first meeting with John Cushing, Wu Bingjian was in his early 30s and had recently lost a 16-year-old son; it was perhaps this that caused him to look upon the boy’s plight with sympathy. In any event, John Cushing soon became “like a son” to Wu Bingjian, who guided the lad in setting up his business and gave him interest-free loans. With Wu Bingjian’s help, the once-penurious Yankee boy became a millionaire and, upon his return to Boston, was regarded as one of the most eligible bachelors in the land.

After Cushing’s departure from Guangzhou, his place at Russell & Co. was taken by another impecunious Perkins relative, John Murray Forbes. Along with his brother Robert Bennet Forbes, John Murray made a fortune in China and became a great American tycoon, leaving a legacy so lasting that the family name is still an icon of American capitalism.

John Forbes’s path to success was very much like that of his uncle, John Cushing. He too grew up in straitened circumstances, but in a family that had important commercial and educational connections: In addition to Thomas Handasyd Perkins, another of his uncles was the head of Phillips Exeter Academy. On arriving in Guangzhou in 1830 as a boy of 17, John Forbes was shoehorned into Russell & Co. by his family. Soon, he and his brother Robert were also on quasi-familial terms with Wu Bingjian (who was also known as Howqua) and his clan. Years later, John Forbes would write:

Howqua, who never did anything by halves, at once took me as Mr Cushing’s successor, and . . . gave me his entire confidence. All his foreign letters, some of which were of almost national importance, were handed to me to read, and to prepare such answers as he indicated . . . before I was eighteen years old it was not uncommon for him to order me to charter one or more entire ships at a time, and load them. The invoices were made out in my name, and the instructions as to sales and returns given just as if the shipments were my own property, and at one time I had as much as half a million dollars thus afloat.

The two Forbes brothers eventually became Wu Bingjian’s investment managers in the United States. Through them, the Wu clan invested hundreds of thousands of dollars in the mid-19th-century American economy. All of this was done on trust, without any written contracts, yet the families continued to honor their obligations to each other long after Wu Bingjian’s death in 1843.

Since opium was transported mainly by ship, it is not at all surprising that shipbuilding and carpentry became avenues through which many prominent families found their way into the trade. Among these, there was one that would become exceptionally renowned: the Delano clan. Originally of Flemish origin, the founder of the American branch of the family, Philippe de Lannoy (“Delano” is thought to be a contraction of the name), settled in New England in 1621, at age 19, residing initially with an uncle who had arrived the year before on the Mayflower. He participated in the massacre of the Pequot tribe and acquired large tracts of land in New England. One of his descendants, Samuel, a shipbuilder in Duxbury, Mass., was the father of shipwright and master mariner Amasa Delano, who traveled to, and resided in, Guangzhou several times in the course of an extraordinarily eventful life. He was also the author of a noted maritime memoir based on his three circumnavigations of the earth: A Narrative of Voyages and Travels in the Northern and Southern Hemisphere. It was in this memoir that Herman Melville found the materials for Benito Cereno: The incident on which the story is based occurred in 1805, when Amasa Delano came upon a drifting Spanish slave ship, the Tryal, while transporting sealskins from Chile to China. Delano was none other than the story’s real-life narrator.

It wasn’t Amasa, however, but a Delano from a collateral branch who forged the family’s connection with the opium trade: Warren Delano Jr., who arrived in Guangzhou the same year as Will Irving and quickly became the head of Russell & Co.’s offices in the city. He was joined there by his half-brother Edward, who also became a partner in the company. Together, the two Delano brothers held a majority stake in the biggest American opium-trading company for decades. Under Warren Delano Jr.’s leadership, Russell & Co. outdistanced every other American company in its opium holdings.

Through the first opium war (1839-42), Warren Delano Jr. remained in China, serving, for a part of the time, as the honorary consul of the United States in Guangzhou, a position he was well equipped to fill, not only because of his prominence as a merchant but also because he was sympathetic to the Chinese cause. In this, he was not alone: Many other Americans also disapproved of the British assault on China and privately wished that the Chinese were better able to resist. Warren Delano Jr. even helped the Chinese defense forces acquire their only Western ship, the Cambridge. He, along with other members of Russell & Co., also aided Wu Bingjian’s clan, warning them of attacks, tipping them off about when they needed to evacuate, and protecting them from incurring losses on their cargoes.

But the Delano brothers were also among those who benefited the most from the First Opium War, making windfall gains after the British withdrawal from Guangzhou. And even though Russell & Co. briefly abjured the opium trade at the insistence of Wu Bingjian, once the war was over they plunged right back into the drug-trafficking business. Like many of their fellow Americans, regardless of their private reservations, the Delano brothers were eager to take advantage of the conditions that the British had violently imposed on China. In the words of one such merchant: “[T]he opium trade is the branch of business which we should most encourage, it is by far the safest and most profitable.”

Nor did the Delanos, or any of their compatriots, doubt that in relation to China—and the non-West in general—Americans and Europeans, whatever their internal differences, needed to act as essentially a single bloc. Even though Westerners were perennially at war with one another, they were entirely in agreement on the necessity of maintaining white supremacy at all costs. The Chinese, for their part, understood very well the relationship between the two English-speaking countries and often referred to Americans as the “younger brothers” of the British.

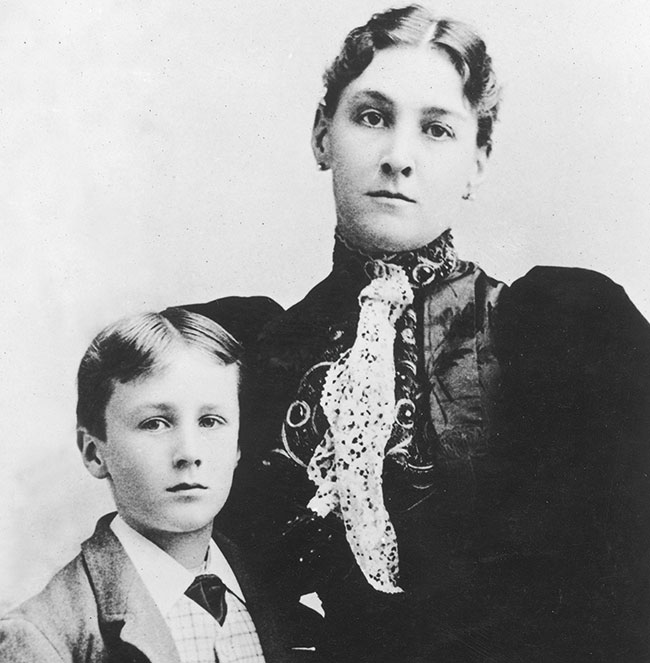

In 1843, after returning to the United States as an immensely wealthy man, Warren Delano Jr. married Catherine Lyman, daughter of a distinguished Massachusetts family. The couple had many children, including a girl, Sara, whose only son, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, became the 32nd president of the United States. Through his brothers and his children, Warren Delano Jr. was also related to the Astors and many of America’s other most prominent families, including that of President Calvin Coolidge.

In 1857, Warren Delano Jr. lost much of his wealth in a financial panic—so, like many other American speculators before him, he returned to the opium trade and quickly rebuilt his fortune. It was at his palatial estate, Algonac, in New York, that Franklin D. Roosevelt’s parents were married.

The story of the American involvement with the 19th-century opium trade is well researched and extensively documented. Yet, even though dozens of books and articles have been published on this subject, it remains largely unknown to the overwhelming majority of Americans, who still tend to associate drug trading with foreigners while continuing to believe that the foundations of American industry were built by exemplars of Puritan virtue. Therein lies the importance of this story: If the role that privileged, upper-class white Americans played in the history of the opium trade were better known, it would surely be more difficult, if not impossible, to impose xenophobic, anti-immigrant framings on issues concerning narcotics, as is still so often done in the United States.