Who is in charge of the Democratic Party? In particular, who is in charge of its strategy and spending? That’s actually a surprisingly difficult question to answer—and it shouldn’t be, at a time when the party and the country face critical challenges that will affect millions of lives for years to come. The next six weeks will see significant turnover in the staffing and leadership of the biggest organizations in the Democratic ecosystem, but many of those decisions will be made in metaphorical smoke-filled rooms, shielded from the kinds of transparency and accountability that are hallmarks of effective and successful organizations.

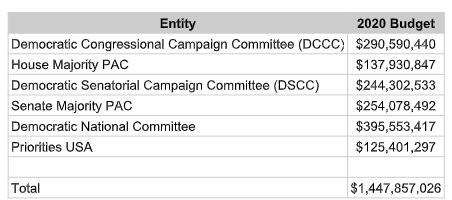

What is commonly called “the Democratic Party” is actually a constellation of six entities that, collectively, spent more than $1.3 billion in the 2020 election cycle.

Even in the most public process—as with the Democratic National Committee, where bylaws clearly explain the process for electing a chair—it remains unclear how to even put one’s name in the hat to be considered for the top job. Despite raising and spending hundreds of millions of dollars from Democratic donors, the super PACs—House Majority PAC, Senate Majority PAC, and Priorities USA—operate with the least level of accountability, frequently making leadership changes without posting positions, searching for talent, articulating the key responsibilities of the position, or even revealing who is in fact doing the hiring.

With respect to the campaign arms of the Senate and House Democrats, the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (DSCC) and the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC), there is some measure of clarity regarding who becomes the chair of each entity. The Democratic senators select their leader, currently Chuck Schumer, and that leader typically picks the chair of the DSCC. On the House side, the members directly vote for the chair of the DCCC (before 2018, the leader of the House Dems choose the committee chair).

While those lines of authority are clear, what happens next is not. The incoming chairs choose an executive director, who then hires the rest of the staff, who in turn run the day-to-day operations.

Over the past decade, dating back to my work in 2008 helping to create a Diversity Talent Bank of 5,000 diverse candidates interested in working in the Obama-Biden administration, I have rarely, if ever, seen a job description circulated for the top staff position of these entities. At best, these poor practices undermine their ability to function at optimal levels. At worst, they result in the kind of diversity debacle that occurred last year, when Congressional Black Caucus and Hispanic Caucus members loudly complained about the overwhelmingly monochromatic composition of the DCCC staff assembled by then–executive director Allison Jaslow.

Absent clear criteria for what the job entails and with no process in place for a healthy range of promising contenders to offer their expertise, the pool of potential people to fill those positions is, almost by definition, limited to the friends and family of a small circle of insiders.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The window for fixing these processes and pulling in the talent regularly walled off from participating in the biggest and richest organizations in the ecosystem is closing fast. Many of the key positions will be filled between now and mid-December, while attention is focused elsewhere.

Now more than ever, Democrats need all hands on deck to analyze what happened in 2020 and chart a course forward. There are no more compelling examples than the results in Arizona and Georgia. The Biden campaign invested little in Georgia, and Arizona did not receive the same level of attention as the Midwestern triumvirate of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania. Yet, winning those Southwestern and Southern states was essential to securing a victory large enough to block Trump’s plans to steal the election through cries of fraud and appeals to the GOP-packed courts (with Trump revealing the game plan on election night, when he said he was going to take his allegations to the Supreme Court). Going forward, given the continuing demographic transformation of the country, smart Democratic leaders will build on those successes in the South and Southwest to solidify and expand progressive power.

Victory in those states was not charted by the handful of consultants who dominate Democratic politics (in fact, in the Report Cards we did in August, we found that Senate Majority PAC had invested $0 of its first $80 million of expenditures in the Georgia Senate races, on which control of the Senate now turns). If the party wants to win, it should learn from those who actually won in what was formerly hostile territory, and bring their insights and understanding into the rooms where it happens. But quick, quiet, closed-door hiring practices inevitably lock out much of the available talent and knowledge.

Although Trump has been defeated, the battle is far from finished, and the stakes going forward are enormous. Despite losing support from some college-educated white voters, Trump brought millions more people to the polls, causing Democrats to lose several House and Senate races they thought they would win. In light of this reality, the next Democratic leadership team must confront several critical questions:

- Why did Democratic candidates fall short of expectations in congressional races?

- What explains the party’s weakness with Latino voters, especially in Florida and Texas?

- What went right in Georgia and Arizona that didn’t translate to Florida and North Carolina?

- What is the right balance—and allocation of resources—between solidifying support in communities of color and trying to hold or increase support among white voters?

- What is the right balance between spending on television ads (still the preferred investment of choice by many consultants) and grassroots mobilization of the kind done in Georgia and Arizona to help turn those states blue?

If the Democrats are going to get it right, they need to pull back the curtain on who is making the decisions, open up the process to the full diversity of the party’s talent, and clearly explain what qualities they are looking for in the leadership of the future. Specifically, they should take four immediate steps:

- Provide transparency in hiring: Job descriptions should be written and widely circulated for all top positions, including executive directors. What are the qualifications? Who exactly makes the hiring decisions? How do you apply—and to whom?

- Insist on cultural competence. Notice I didn’t say “hire people of color” (although, let me say it now, hire people of color!). Too often, consultants think that racial issues are something that only relate to people of color. Cultural competence, however, refers to the ability to also communicate with white people about racial issues. Racial identity is one of most clear-cut determinants of political behavior, and the political environment today is highly racially charged. Trump understands this, and that’s why he was able to garner such enthusiastic support. As a rule, people of color are more culturally competent than white people, because they’ve had to navigate the realities of race and racism their entire lives. Some whites have, in fact, developed cultural competence, but it’s a skill set and talent that’s largely missing from much of the Democratic ecosystem. The incoming staff and leadership will determine how much of the party’s hundreds of millions of dollars will be spent on research seeking to understand why voters of color sit out elections—and how much will be spent on anxious whites fearful about losing their way of life? Culturally competent leadership is critical if we want to productively explore and answer those questions.

- Conduct data-driven post-mortems on the 2020 results: We are seeing lots of recriminations about Democrats’ losing seats in the House, but most of that commentary is driven by fact-free, preexisting biases that are not supported by empirical evidence. The conventional wisdom that the Black Lives Matter demand to defund the police weakened Democratic performance is contradicted by data showing that Democratic candidates actually significantly improved their performance over 2018 (the incumbents who lost fell short despite garnering an average 25 percent increase in votes). The problem was that the Republican increase was even greater. Whatever remedies are pursued in 2021 must be tied to an accurate diagnosis of what happened in 2020.

Calamity has been averted with the defeat of Trump, but entrenched and ferocious opposition to progressive values in a rapidly diversifying nation is only going to increase. If the Democratic Party is going to win the battles to come, it needs to change its hiring practices so that it can find, elevate, and empower people who know how to win the kinds of fights that are on the horizon.