Trump’s Mogul-First Model of Diplomacy

The pundits straining to seek coherence in the new interventionist “Donroe doctrine” would do well to look back to Trump’s roots in New York real estate

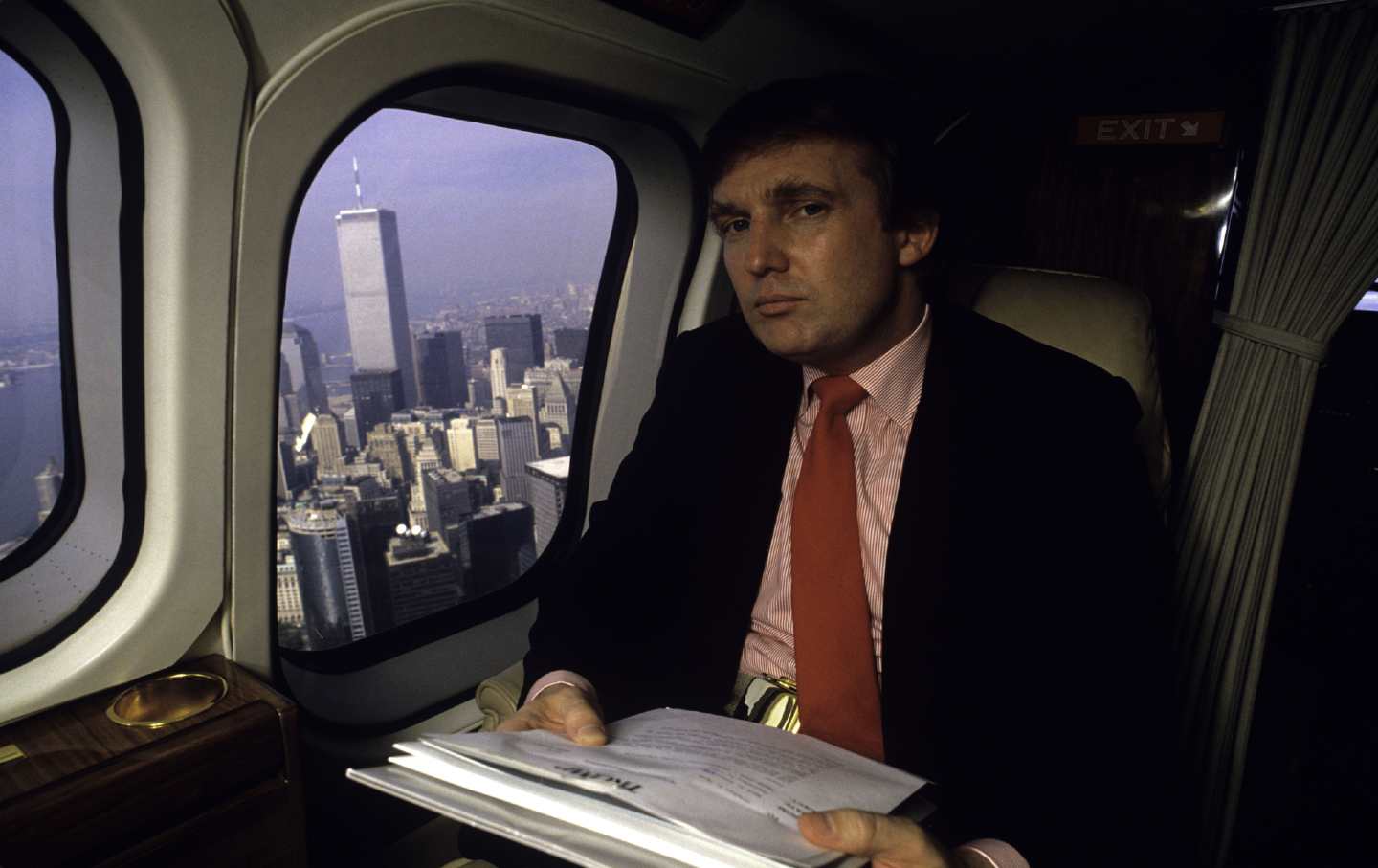

Donald Trump surveys the Manhattan skyline in 1987.

(Joe McNally / Getty Images)In 2018, an unnamed staffer in the first Trump administration shot down the notion that anything Trump did was strategic or sophisticated in a quote that has circulated prolifically since. Trump was not playing “the sort of three-dimensional chess people ascribe to [his] decisions,” the aide said. “More often than not he’s just eating the pieces.”

I’ve been thinking about that quote in the last few days, especially as various pundits and talking heads attempt to describe Trump’s illegal abduction of Venezuelan dictator Nicholas Maduro as some kind of strategic effort to establish or buttress the United States’ “sphere of influence” in Latin America. Trump watchers have also highlighted the mention of the Monroe Doctrine in November’s National Security Strategy document setting out the MAGA vision of US hegemony. But that manifesto is little more than a word salad of buzzwords and military jargon—evidence that the C students who wrote it did not do the assigned reading. The first page attempts to define the word “strategy” in a way betraying the authors’ struggle to understand it; indeed, throughout the document, the authors lean on the half-assed ploy favored among junior-high essay writers who find themselves in over their heads, citing dictionary definitions of a concept or phrase to sound authoritative.

As a middle-aged adult of sound mind with, incidentally, a degree in public policy studies and political science, I completely understand the impulse to look at what’s happening and find some rational explanation for it that does not involve Donald Trump with a colon full of chess pieces. We want some level of certainty, and we want to find patterns so we can predict his behavior and respond to it, because the alternative is far more terrifying. If he does not have any real strategy, the implication is that his decision-making is driven by whim, ego, whatever he had for breakfast this morning, or saw in an action movie from 1998.

Yet it seems clear that the more chaotic and random theory of the case offers the fullest explanation. Very little in Trump’s behavior can be explained by the evolution of American Grand Strategy or burrowing deeply into Thucydides or Morgenthau. And the people around him who might have a coherent idea of what the plan might be are also the ones exerting the most limited influence on his thinking.

This is not to say that there’s no model at all that accounts for the president’s decision-making. Based on Trump’s zero-sum view of most human interactions, it’s safe to say that his guiding foreign policy doctrine comes from his experience with commercial real estate in New York City, particularly during the peak of his career in the late 1980s. Trump didn’t enjoy the respect of the Manhattan elites he wanted to impress, but he was becoming famous nationally. That meant he basked in celebrity culture and the trappings of ’80s excess—and at that point, most New Yorkers were not openly hostile to him. In the same way that a person who peaked in high school might remain developmentally mired in that life stage, Trump only approaches the world in which he now wields vast and destructive power as another version of his world then, only bigger.

Most importantly, he is not interested in pursuing spheres of influence, but spheres of ownership. Trump believes there is nothing he cannot own or buy or manipulate someone into giving him. This week, we are being subjected to yet another round of his threats to buy Greenland because he thinks that buying another country is no different from acquiring real estate (what is a country if not a specific parcel of land?) and his toadies and many people in the media insist on playing along.

This is ridiculous, of course. But it’s also what you’d expect from a real estate guy whose entire understanding of international relations consists of viewing places and people abroad in terms of per-square-foot cost and monetization opportunities. That’s why Trump’s proposed solution to Israel’s genocidal war in Gaza is to purge the territory of Palestinians and build a luxury resort on the spot—the “Riviera of the Middle East,” as he likes to put it. It’s also why, in another posting binge on Truth Social, Trump announced that he’s reached a deal with Venezuela to deliver 30 to 50 million barrels of oil to American shores, which he will evidently use to create a free-standing personal slush fund. This arrangement is stunningly illegal and unconstitutional; what’s more, it would likely cause profits to plummet for American oil companies by glutting the market. But none of that matters to Trump; resource hoarding is proof of dominance, and thus a self-evident mandate.

The same warped calculus was at the bottom of the illegal raid on Caracas that kidnapped Maduro and his wife. Democracy and drug cartels are not his underlying motivation. It turns out, in fact, that the ginned-up federal indictment of Maduro initially accused him of collaborating with a drug gang called Cartel De Los Soles—a reference that was clumsily scrubbed from the document when prosecutors realized that no such group exists. Details like verifiable charges and plausible evidence simply don’t matter to Trump. He’s only driven by a near pathological obsession with acquiring assets that he believes are his birthright as an ’80s-branded Master of the Universe.

To the chagrin of his aides, he admitted as much when he said we invaded Venezuela to “take back” the oil reserves that the country nationalized in 1976 —implying that it rightfully belongs to the United States and that advancing democracy was not exactly preeminent on his mind.

New York City real estate is dynastic and insular. While most of the multigenerational real estate moguls here are not as vulgar and self-obsessed as Trump is, they remain for the most part obscenely rich people who enjoy flashy displays of power and excess. Like Trump, they believe they’re licensed to reap maximum gains and wreak maximum civic havoc as a de facto divine right. God has chosen them to vandalize the New York skyline with gargantuan super-tall monuments to their own vanity while fighting the most modest efforts to make New York City affordable for their lowest-paid employees. And like Trump, they surround themselves with a retinue of toadies to grease the wheels of their rapacious wealth accumulation— corrupt municipal officials, local mobsters, armies of lawyers and PR people. For the most part they live in a bubble that consists largely of other rich people who live in an identical milieu. World events matter only inasmuch as they affect one’s net worth.

So it’s unsurprising that Trump wants to acquire Greenland, and the Panama Canal, and Canada. Since this Venezuela project doesn’t seem to be getting any pushback from Congress or anyone who can constrain him, why not Colombia, Cuba, Nigeria—or really, any country that flits across his brain pan as a likely storehouse of valuable natural resources? There is no sphere of influence that triangulates Greenland, Panama and Nigeria, but that was never the point. In New York, you accumulate power by buying up everything, controlling the skyline, the air rights, the politicians. Why would international affairs be any different?

This mobbed-up model of world order is especially attractive if you can recruit officials and consiglieres to maintain it. If Trump paid any attention to America’s imperial adventures in Latin America, it was during that same stretch of his real estate ascendancy—say 1989, when Panamanian President Manuel Noriega was indicted on charges of racketeering and money laundering. Noriega was useful to the United States and willing to do America’s bidding in the region—until he wasn’t, and then he was convicted in American courts on charges of drug running. Trump doesn’t have a problem with Latin American authoritarians, as evidenced by, among other things, his perverse affection for Jair Bolsonaro. Perhaps Nicolas Maduro would be relaxing at home right now (or at least in Turkey, as initial deals to secure his voluntary relinquishment of power had reportedly arranged) if he had managed to play a version of Noriega—a regional flunky who had outlived his usefuleness—for the Trump mob. Instead, he is sitting in a prison complex in Brooklyn, nominally for trafficking cocaine, after the initial propaganda campaign to link up Venezuela with the American fentanyl crisis also proved a bust. In one way, though, the charge is entirely fitting, since cocaine was the Manhattan power elite’s preferred party drug of 1989.

Perhaps the most distressing feature of Trump’s mogul-ized brand of American diplomacy is how it insulates him from the actual consequences of his decision-making. In his press conference after that Caracas raid, he gleefully described Delta Force units snatching Maduro as though it were footage from a TV espionage show. He likewise has characterized drones blowing up fishing boats and Nigerians as if they’re simply spectacles and not real-world violence ending the lives of actual human beings. Other countries are just places where you can own property and other assets and do deals and make money. Foreign affairs are primarily a thing that happens on TV, away from the dinner parties and the golf junkets that really matter.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →“Some close observers of Mr. Trump, including officials from his first administration, caution against thinking his actions and statements are strategic,” The New York Times reported in May. “While Mr. Trump might have strong, long-held attitudes about a handful of issues, notably immigration and trade, he does not have a vision of a world order, they argue.”

This is both true and not. Trump does not have a vision that is rooted in any concern for global affairs and the populations affected by his decisions. But he does relish a vision of a world where he is a popular and dominant boy king, and he has all the toys—or at least the ones he hasn’t already eaten.

More from The Nation

Trump’s Iran War Could Be an Even Bigger Catastrophe Than Iraq Trump’s Iran War Could Be an Even Bigger Catastrophe Than Iraq

Remarkably, Trump seems on the verge of outdoing George W. Bush in reckless, stupid militarism.

We Are All Minneapolis We Are All Minneapolis

ICE attacks are attacks on America.

I’m a Journalist on SNAP. Here’s What I Saw During the Latest Food Crisis. I’m a Journalist on SNAP. Here’s What I Saw During the Latest Food Crisis.

As for virtually all SNAP recipients, my benefits have never been enough to cover monthly food expenses. Meanwhile, Trump calls any food aid at all “un-American.”

Trump’s Attack on the Supreme Court Was Unhinged Even for Him Trump’s Attack on the Supreme Court Was Unhinged Even for Him

The president went on a wild rant alleging that the justices who struck down his tariffs were part of a vast global conspiracy to destroy him.

Why Trump Is Trying to Steal Jesse Jackson’s Glory Why Trump Is Trying to Steal Jesse Jackson’s Glory

The president wants you to know he had a Black friend, sort of.