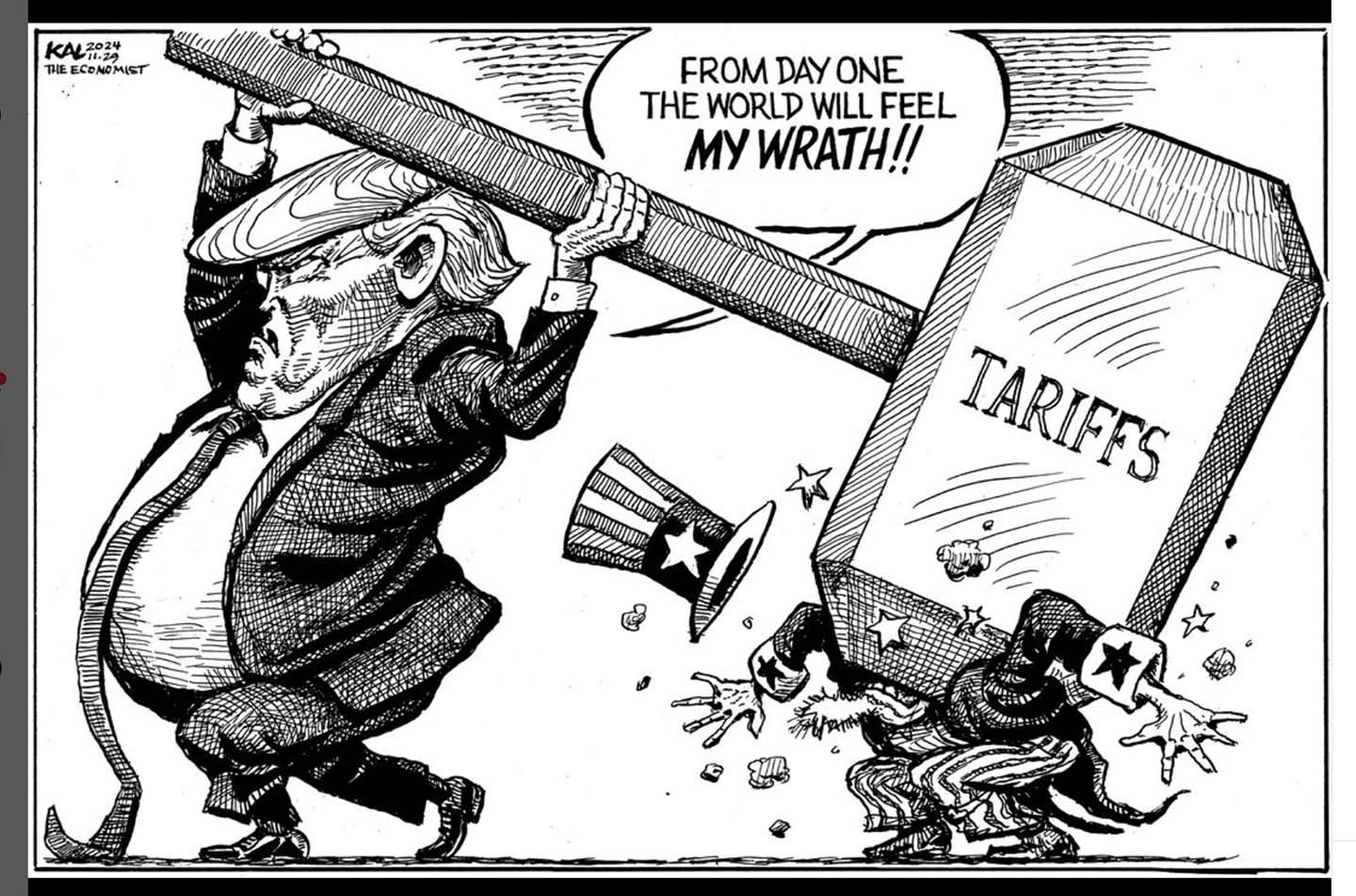

What’s With All the Swole Politicians?

Everywhere you look, a politics guy is sharing an intense workout video. What is going on?

Almost a month before he uttered the words “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country,” President-elect John F. Kennedy took to the pages of Sports Illustrated with advice on exactly how his fellow citizens could fulfill his imminent mandate. One thing Americans could do for their country, he wrote, was lose the flab.

In an essay called “The Soft American,” Kennedy framed an out-of-shape nation as a “menace to our security” amid the escalating global tensions of the Cold War. Calling “physical vigor” one of “America’s most precious resources,” Kennedy proposed establishing the White House Committee on Health and Fitness and said that ensuring physical fitness was partially the responsibility of the federal government. He also painted exercise as a boon to “creative intellectual activity,” not simply a pursuit of physical perfection. “The relationship between the soundness of the body and the activities of the mind,” he wrote, “is subtle and complex.”

If JFK’s exhortations for America to pump itself up had a decidedly macho tinge, at least he alluded to fitness as part of a balanced human condition. His nephew, current presidential hopeful Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has a less complex, and more lunkheaded, message.

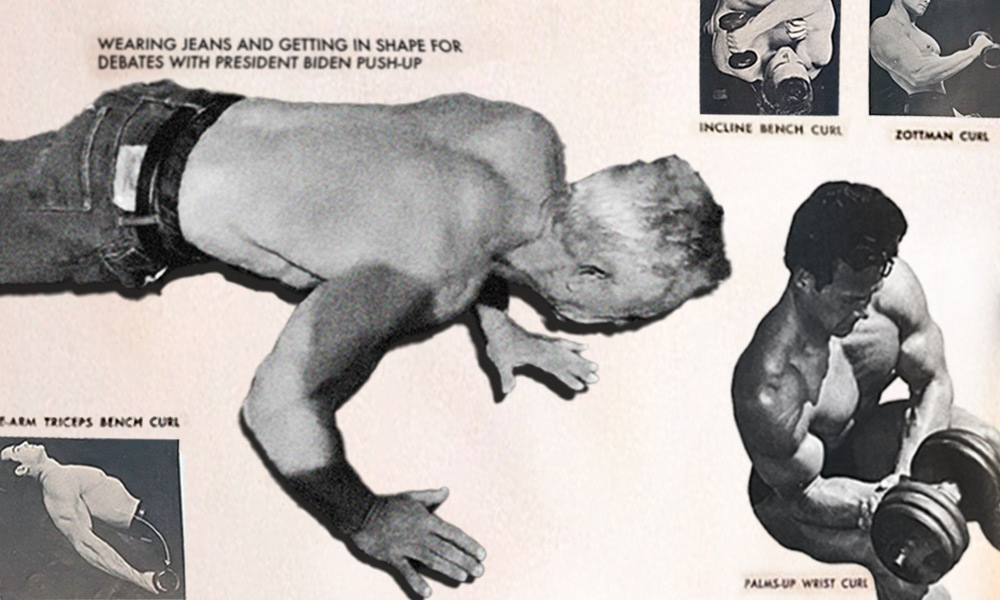

If asked to picture debate prep in their minds, most people might imagine a person’s nose buried in books or a candidate sparring with advisers on key topics. Kennedy’s vision is a bit different. In a June 25 semi-viral tweet, he said he was “getting in shape” for his debates with President Biden—debates that do not currently exist and will most likely never happen—by working out shirtless. After doing a total of nine push-ups, the 69-year-old Kennedy was visibly straining to finish, but his main goal was probably accomplished: In just a few days, CNN had taken the sweat-soaked bait and reported on the candidate’s workout.

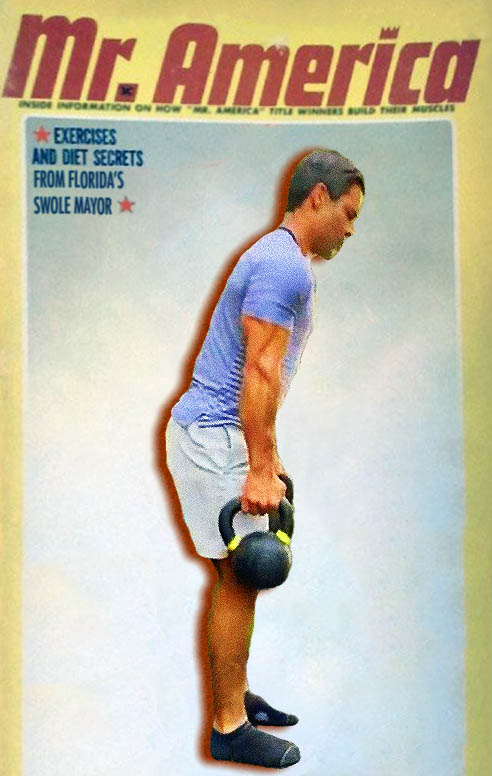

Since Kennedy’s tweet, several other politicians, on both sides of the aisle, have joined in and let America know that they are hitting the gym. On Independence Day, Miami Mayor Francis Suarez, who is running for the Republican presidential nomination and frequently posts workout videos, bragged that he placed sixth in a 5k run. Two days later, Representative Jamaal Bowman, a Democrat from New York City, issued a plea to his followers to “center [their] health and well-being” in the fight against democracy as he lifted 405 pounds. While labeling this as the “testosterone primary,” Politico even commented that the phenomenon was “getting out of hand.”

As JFK’s essay shows, fitness has forever been a theme in American politics. But this election cycle has created fertile ground for bodily concerns to take center stage. “Tests of physical strength are gonna play a much bigger role,” Natalia Petrzela, a historian at the New School and author of Fit Nation, told The Nation.

As Biden’s first term comes to a close, and the 80-year-old’s every physical slip-up makes national headlines, a growing number of voters perceive him as too frail to seek a second term. Biden would be 86 if he completed a full second term—nearly a decade older than Ronald Reagan was at the end of his tenure. And he is all but certain to face Donald Trump, whose physical health has been scrutinized in its own complicated ways. Twenty twenty-four will thus provide the country with as potent a lens on how our relationship to exercise, our bodies, and masculinity affects our politics as we’ve had in a long time. It will also serve as a reminder of how the American obsession with individual personal behavior, rather than systemic change, continues to impede the actual implementation of sound health policy.

The concept of the “body politic” posits that an entire nation could be thought of as one physical body composed of its people, with its ruler as the head. There’s no doubt that some Americans are yearning for a buff body politic, whether or not it’s what’s best for the country or even makes much political sense. But while this penchant for pecs may be trending at the moment, it’s also an entrenched part of America’s political lore.

History is littered with politicians who underscored their own musculature as a stand-in for their aptness for office. As far back as Teddy Roosevelt, who subscribed to an ideology known as “muscular Christianity,” presidents have used their muscles as a synecdoche for moral upstanding. In the past few decades, presidential exercise has been a key public relations tool—think of Bill Clinton’s infamous jogs, George W. Bush’s cycling mania, or Barack Obama’s swimsuit shots and basketball prowess. (Biden is also a cyclist, though, unfortunately for him, the most bike-related news he’s made was when he fell off of one.)

Roosevelt believed that we should “admire the man who embodies victorious effort,” one who has “those virile qualities necessary to win in the stern strife of actual life.” In many ways, voters believe the same, just as Americans often conflate manliness with leadership. “Masculine traits, especially for the presidency, are the key desirable traits,” Monika McDermott, a professor of political science at Fordham University, told The Nation. “Compassion, things like that are nice, but what people want is someone who’s powerful, assertive, aggressive: a leader.”

While the association between gym time and political aptitude spans both sides of the aisle, the connection between conservative politics and physical fitness really dates back to Barry Goldwater, the American senator who not only emphasized his own fitness during his 1964 presidential campaign—“G.O.P. Candidate Keeping Fit Despite Campaign Pace—Muscle Tone Excellent,” reads a New York Times headline from that year—but also shaped the modern Republican Party. That influence is still seen in the way Republicans emphasize bodywork today, including Paul Ryan’s “All Pumped Up for His Closeup” Time magazine cover and Marjorie Taylor Greene’s CrossFit videos.

Republicans bank on this emphasis on the discipline of a fitness routine being conflated with perceived masculine politics, like fiscal discipline and aggressive foreign policy. “People confuse muscularity with masculinity a lot of the time,” McDermott said. But while Republicans want to stand in contrast to Democrats, who are often perceived as feminine or weak, the reality is not as simple as a masculine-feminine dichotomy. (Besides, Democrats are not immune to political fitness cults; Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s workouts became such a key part of her iconography that her personal trainer did push-ups next to her coffin.)

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Rather, this might be better understood through the lens of what sociologist Raewyn Connell called multiple masculinities, a term Connell coined to describe how there are many versions of masculinity that are informed by realities like class and race.

The multiple masculinities concept allows us a wider frame with which to analyze both Biden’s and Trump’s relationships with masculinity, since both men defy the stereotypical masculine ideal in their own ways. It’s also useful because what’s happening right now, between Biden, Trump, and a new crop of hopefuls looking to snag the presidency from them, is a “tug-of-war between multiple expressions of masculinity,” according to Michael Messner, a professor of sociology at the University of Southern California who has also written about muscularity in politics, specifically in regards to Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The masculinity of the moment is often best understood as a reaction to the masculinity that came before it. While younger, more physically fit candidates seek to contrast themselves with Biden and Trump, Biden himself tried to embody a form of paternal masculinity, one that seeks to protect and care for a divided nation. That characterization is a contrast to Trump’s blistering, bloviating masculinity, which not only downplayed physical fitness and upped the ante on mercurial aggression but also stood in contrast to the family-man persona and highly regimented exercise routine of Barack Obama.

It’s certainly true that muscles are not at the top of everyone’s wish list during every election. During the 2020 election, a slate of septuagenarians was duking it out for the office, with Biden’s chief rival being Bernie Sanders, who was both older and more cantankerous than the eventual president. And fitness was clearly not on the mind of voters when they elected Trump, who ascribes to the theory that people, like batteries, have a finite amount of energy, which means that exercise was wasting a nonrenewable resource. Trump chose not to perform his masculinity in a way that emphasized physicality. Instead, he crafted an entirely persona-driven vision of masculinity, one based on bravado, cruelty, the denial of illness—such as when he purported to be working diligently through his own Covid diagnosis rather than show weakness—and the total denigration of women. He also tried to turn other men into his accomplices, such as when he chalked up admissions of sexual assault to standard “locker room talk.”

But the current ascendance of exercise in politics is not just a reaction to Biden and Trump. Aside from distancing themselves from the front-runners’ own perceived physical or mental weaknesses, this return to pumped-up masculinity can also be seen as a response to the Covid pandemic. More than three in five Americans say that the pandemic has made them more concerned about their overall health as a result of the pandemic, according to data from the World Economic Forum. To many people, the pandemic meant a more sedentary lifestyle, which has resulted in a greater emphasis on both at-home and at-the-gym fitness routines.

That individualistic turn also reflects the wider collapse of any collective response to the pandemic. As the right has grown increasingly suspicious of vaccines, and the federal government walks away from its public health responsibilities, people have turned instead to an individualistic response to external viral threats, especially physical fitness. It’s why doctors who stress the safety of vaccines, such as Dr. Peter Hotez, have become targets of the right-wing commentator class. Joe Rogan invited Hotez on his podcast several times to debate Kennedy. Hotez turned down the invite, further fueling right-wing rumblings that he is unprepared to verbally spar with Rogan and Kennedy, both of whom stand in physical contrast to the decorated doctor. This contrast even became the subject of a minor political Twitter meme in which one Rogan devotee put a face-only picture of Hotez next to a picture of Rogan and Kennedy’s bulging muscles, complete with the caption: “Who would you rather take health advice from?” Just one day later, Missouri Representative Eric Burlison swagger-jacked the tweet, this time removing RFK and juxtaposing Rogan and Hotez, with a near-identical caption.

Though Kennedy is running as a Democrat, he is making a pretty transparent pitch to independents and Republicans. His strategy has included appearances on conspiracy-friendly right-wing podcasts. He has also appeared on platforms with noted anti-trans provocateur Jordan Peterson and former Project Veritas leader James O’Keefe. This has worked out pretty well in RFK Jr.’s favor: Only about one-fifth of his top contributors give exclusively to Democrats.

Kennedy’s emphasis on exercise and his own embrace of conspiracy theories can be seen as an individual-level response to mistrust of larger institutions, something that has proliferated across the political spectrum since the onset of the pandemic. If the world is full of shadow organizations and unknown ne’er-do-wells, then a return to individualistic self-determination, even if it’s just determining the size of your muscles, makes sense.

If a person’s fitness is their individual responsibility, then the federal government is off the hook, a political philosophy that is actually at odds with RFK’s uncle. But JFK’s declaration that the primary reason to exercise is so that we can all be ready to do battle against America’s declared enemies carries its own kind of toxicity.

Rather than being wielded as a weapon in a campaign, or a sort of device to indoctrinate American nationalism, exercise could be viewed as a benefit for all Americans that should be easily accessible and available to those who want it. Much of the current emphasis on musculature is simply political theater, absent any political agenda or structural solutions to Americans’ health. Petrzela said that there are policy proposals that candidates could embrace if they were actually keen on getting Americans to be fitter, including investing in substantial physical education curricula in schools and in well-lit parks and safer streets that would allow people to take long walks, and even embracing affordable housing policies that would allow people to live close to work and not have to spend most of their day commuting.

“The idea that people are not healthy or not exercising primarily due to a lack of will is a simplistic argument,” she said. “Those same people who make that critique should say, ‘What can we do to create structures where it’s not just ladies who can afford to go to SoulCyle and yoga who have these options?’”

Rather than arguing that everyone should be forced to participate in calisthenics, Petrzela instead said that, if politicians are indeed going to emphasize physicality, it should not be under the motto of fitness for me but not for thee. However, the current iteration of health that we’re being fed this election cycle reflects the larger feelings on health across parties. Embracing politicians who espouse an individualistic idea of health and wellness without advocating for policies that can make fitness possible for everyone, is akin to having a swole neck while skipping leg day—and arm day, and glutes day, and every other day. We live in a nation that outspends every other developed nation on health care while not guaranteeing universal coverage or enjoying better health outcomes—and it’s political action, not push-ups, that will change that.

More from The Nation

Enough With the Bad Election Takes! Enough With the Bad Election Takes!

To properly diagnose what went wrong, we need to look at the actual number of votes cast.

No, Kamala Harris Staffers Did Not Run a “Flawless” Campaign No, Kamala Harris Staffers Did Not Run a “Flawless” Campaign

Democratic strategists are still patting themselves on the back for a catastrophic defeat.

The Courts, Trump, and Us: A Q&A With David Cole The Courts, Trump, and Us: A Q&A With David Cole

Last time, the courts were an essential checking force on the Trump administration. This time around, they may again provide a check—if we push.

Congresswoman Barbara Lee on Why Shirley Chisholm Was Right Congresswoman Barbara Lee on Why Shirley Chisholm Was Right

The California Democrat explains why, during her 25 years in Congress, it was important for her “to disrupt and dismantle and build something that’s equitable and just and right.”...