This Bill Aims to Strip Trump’s Immunity—and the Supreme Court’s Power

In a sign that Democrats are finally getting serious about reining in the Supreme Court, Senator Check Schumer has proposed the No Kings Act.

Protesters gather outside the Supreme Court Building on July 1, 2024, the day the court issued its decision in Donald Trump’s immunity case.

(D(Drew Angerer / AFP via Getty Images)

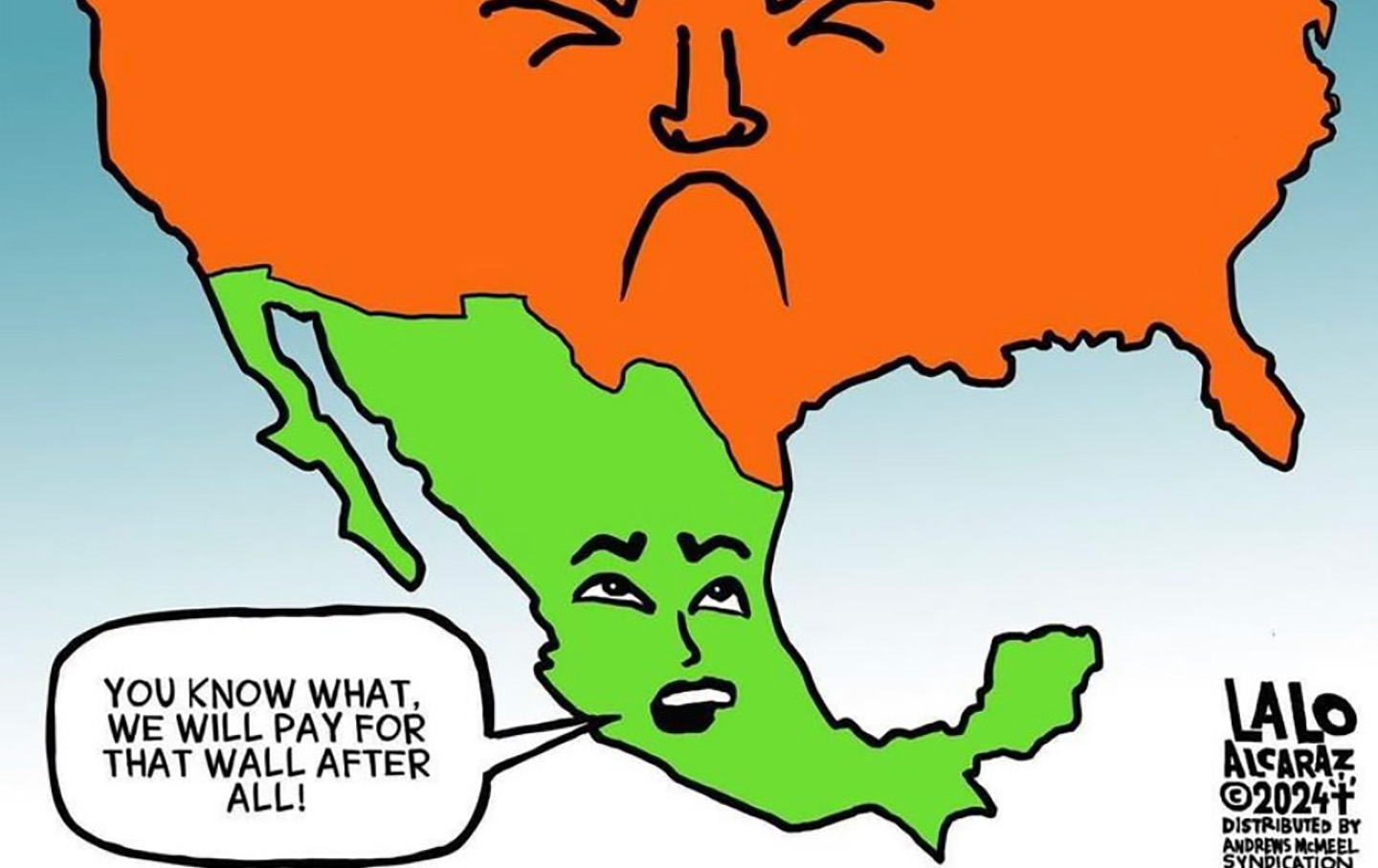

I think it is fair to say that the Supreme Court’s decision, on the last day of its term, to grant Donald Trump absolute immunity from prosecution for crimes he may have committed while acting as president has woken the Democratic party up from its long, deferential slumber. For the first time in 40 years, the party appears ready to take on the Republicans who run the Supreme Court, specifically over the issue of whether the president of the United States is subject to the laws of the country.

Early last week, President Joe Biden called for a constitutional amendment to ensure that presidents can be charged for crimes they commit while going about their presidential business. But passing a constitutional amendment is a long and arduous process. Then, late last week, Senate majority leader Charles Schumer proposed a quicker solution: the No Kings Act.

Schumer’s bill would make it so that presidents and vice presidents, as well as former presidents and vice presidents, “shall not be entitled to any form of immunity (whether absolute, presumptive, or otherwise) from criminal prosecutions for alleged violations of the criminal laws of the United States unless specified by Congress.” The legislation would flatly overturn and revoke the immunity invented by the Supreme Court for Donald Trump.

This alone is a significant step. But the most important part of the legislation is that it attempts to SCOTUS-proof the legislation so that the Supreme Court cannot simply ignore the will of Congress. The bill states that the Supreme Court “shall have no appellate jurisdiction” over the act. This means that the court cannot declare the bill unconstitutional or use another case to restore the absolute immunity the bill takes away. Instead, the bill specifies that any objections to the constitutionality of the legislation must be filed in Washington, DC, and heard by the Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit.

The idea behind this provision is what scholars call “jurisdiction stripping.” Most of the cases the Supreme Court hears come to the court on appeal from a lower court. But the Constitution says that the court’s appellate jurisdiction is subject to “exceptions” and “regulations” made by Congress. Arguably, Congress has the power to tell the Supreme Court what it can review—and what it cannot. Schumer’s bill would test that theory by preventing the court from reviewing the act.

Schumer’s legislation is creative and it signals that Democrats in Congress are finally willing to use some of the power the Constitution bestows on Congress to fight the Supreme Court. The problem, however, is that the conservative supermajority on the Supreme Court is unlikely to think that it can have its jurisdiction stripped in this matter. People who have been paying attention know that the Republican-appointed justices on the court are quite happy to make ridiculous, unprecedented arguments in the service of their preferred political agenda. Indeed, the only reason the No Kings Act is even necessary is that the conservatives made the ridiculous, unprecedented argument that the Constitution holds presidents above the law. So it wouldn’t be out of character for them to simply make up a reason to kill the act.

But in this case, the argument Republicans are likely to make against the No Kings Act isn’t actually completely ridiculous, and does have some precedent. As Ian Millhiser explains over at Vox, there’s a credible argument that Congress cannot strip the Supreme Court of jurisdiction in cases where the court has already ruled. Since the court has said that Trump is entitled to immunity as a constitutional matter, there is a legitimate argument to be made that Congress cannot come in after the fact and say that the court isn’t allowed to rule on presidential immunity. And even if it does, the DC Circuit could feel bound to abide by the Supreme Court’s prior ruling.

At least, that’s the argument Republicans and their friends on the Supreme Court will make. As I explained in The Nation over two years ago, the fundamental problem with jurisdiction stripping as a court reform is that the Republican Supreme Court will always argue that its jurisdiction cannot be stripped.

Congress could, of course, simply ignore what would be a statutorily illegal adverse ruling from the Supreme Court, but, remember, we are talking about whether a president like Trump can be prosecuted for crimes. You don’t have to be a Civil War historian to imagine the sheer levels of constitutional crisis that could happen if this law is passed, Trump is prosecuted, his justices on the Supreme Court say he can’t be prosecuted, and the prosecution goes forward anyway.

Luckily, that is putting the cart too far before the horse. First, Democrats have to win the House, keep control of the Senate, and defeat Trump in the upcoming presidential election. Then, Democrats would have to pass this bill, which would probably involve getting rid of the filibuster in the Senate. Then, Trump would have to be prosecuted again. Then, the Supreme Court would have to be willing to risk an open revolt against their authority to once again save their recently defeated political candidate from accountability. Finally, the lower courts would have to side with Congress over the Supreme Court on the interpretation of the Constitution. That’s a whole lot of ifs and maybes before we get to a full on constitutional crisis.

So where does that actually leave us?

Like Biden’s court reform proposals, what’s significant about Schumer’s bill is not its likelihood for success or the chance that it will ever put Donald Trump behind bars. What’s important is that it signals that the Democrats are finally willing to play constitutional hardball with the Republican court. The Supreme Court’s time of ruling over the country, unbothered and unchecked, feels like it is nearing an end.

If the Democrats win the trifecta, they will pass something to reform the court and reduce its power. The Republicans on the court will reject those reforms and declare them unconstitutional. And then we will see if the Democrats have the will to do the one thing the Supreme Court cannot reject: expand the number of justices to give the pro-democracy justices a majority on the court.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The road toward court reform leads to court expansion or it leads to nowhere. Biden, and now Schumer, are willing to take the first steps.