Can Nevada Democrats Beat the Odds?

By most measures, Nevada is a blue state. But Democrats could be placing a risky bet there this November.

Three miles north of the glitzy resorts and casinos of the Las Vegas Strip, the Fremont Street Experience offers a glimpse of an older, rawer Sin City. Instead of lush fountains and marble statues, it has a curved arcade ceiling consisting of countless LED panels that conjure up endless permutations of psychedelic light displays; instead of fancy, sexy revues in tastefully decked-out theaters, it has scantily clad young women in fishnet stockings and feather boas, walking up and down the street inviting tourists to take photos with them in suggestive poses; instead of billion-dollar pleasure palaces with fine dining, sprawling casinos, and designer stores, it has neon-illuminated dive bars and tourist restaurants, dimly lit gambling halls, and kitschy hole-in-the-wall tourist shops, many of them—like their counterparts in New York City’s Little Italy, California’s Venice Beach, and myriad other tourist destinations—selling clothing with provocative slogans.

In front of one of these stores, a shirt declares: “I came here to drink and FUCK and I’m almost done drinking.” A pair of women’s shorts is emblazoned, on its rear end, with the message “Fuck it like you stole it.” And there are Trump T-shirts—lots of them. One with the ex-president’s mug shot and the word “Legend.” Another with his smirking face against a large American flag and the question “Miss me yet?” Another bears the Trump mug shot and, in Gothic script, the motto “Thug Life.”

For Nayela Gomez, the manager of one of these shops, stocking the Trump shirts was an easy business decision. “They sell really good,” she says, wearing a thick knit hat to ward off the winter cold as she cleans the windows near her cash register. “He’s a good seller.” As far as Gomez is concerned, it isn’t about politics or elections. “I don’t get into politics,” she says. “I sell what people want. He’s not president now, and everyone likes him.”

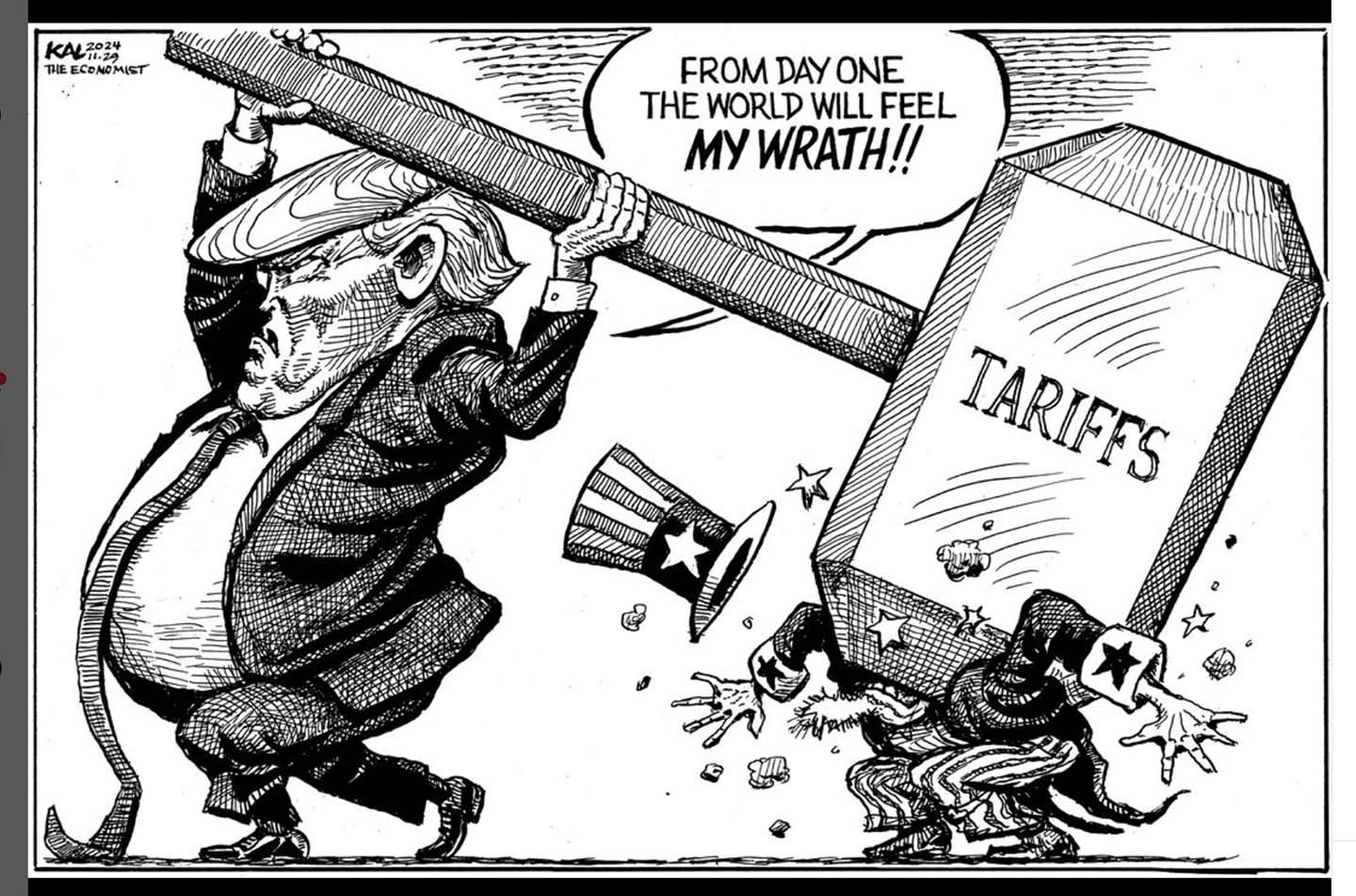

Thirty years ago, shirts with a vaguely transgressive, screw-the-system political message might have featured a picture of Che Guevara or Malcolm X. These days, with the anger in the political atmosphere taking the form of right-wing populism, and with the public stuck in a foul mood about everything from the legacy of pandemic public health policies to inflation, the southern border, and the wars in Ukraine and Gaza, the face of that message is Donald Trump. It speaks volumes about where America’s troubled political culture is these days, when a combination of alienation, political exhaustion, and cynicism could return Trump to the White House despite—or, God forbid, even because of—his two impeachments, his being found liable for sexual abuse, and his 91 felony counts.

Twenty-three-year-old James Cain, who attended the University of Nevada at Las Vegas before dropping out, can see the appeal. Cain is disillusioned with politics in general and, even though he thinks Trump is “garbage,” is considering voting for him in 2024, simply because he says things that make Cain and his friends laugh. He is cynical enough to believe that many politicians are only in it for themselves, and like so many Americans today, he is deeply suspicious of any politician’s ability to change a status quo that, with high student-loan debt, unaffordable housing, and several years of a pandemic followed by inflation and rising interest rates, isn’t working for him and his friends. And so, he intends to vote for the clown. Cain regards the revenge-obsessed ex-president as more of a loud-mouthed cable TV comedian or a YouTube influencer than a deadly serious demagogue.

“I think Biden is far too old to effectively lead our country,” Cain says. “It’s not good for his health, and it’s not good for our country. I just think of a very, very tired old man who has been in this game for a very long time. I’d vote for Trump over Biden, because while Trump is stupid and a blatantly ignorant person, I don’t think either will make executive decisions that will dramatically impact our country, and I think Trump would be far more entertaining. It would be for entertainment value. He’s funny to listen to, and he doesn’t have any etiquette at all—he’ll just say whatever.”

Hunter Cain, a 42-year-old military veteran with an astounding nine university and associates’ degrees, is running as a progressive Democrat for a seat on the Clark County Commission. He doesn’t agree with his son James, who is one of 36 young men he has either adopted or served as a foster parent to over the years. He does, however, understand why Biden’s geriatric persona isn’t resonating with young people, and he is only too aware of how fragile the 46th president’s coalition is as he heads into the 2024 election season.

A number of polls in the past few months have shown Trump edging out Biden in Nevada in a hypothetical matchup in November, not necessarily because Trump has become more popular but because Biden has become more unpopular, and even his supporters are unenthusiastic about him. By contrast, Trump—who held several rallies in Las Vegas and Reno in the autumn and early winter—still has fanatical loyalists in his camp, along with, increasingly, once-reluctant Republicans who have made their peace with the idea of voting for a man they know to be loathsome in exchange for getting policies they like on taxes, on the border and immigration, on military spending, and so on.

Hunter Cain says that many of his friends are planning to leave the ballot blank at the top of the ticket. They will vote for state and local officials, but they feel so alienated from and uninspired by Biden—in many cases because of the president’s support for Israel’s war in Gaza—that they won’t cast a ballot for him. Some, he adds, are considering voting for Robert F. Kennedy Jr. or Jill Stein, and others simply won’t vote. “What’s making Trump competitive is the apathy Democrats have right now,” he says. “They’re not ‘feeling the Bern’ with Joe Biden.”

“A lot of folks have exited the Democratic Party and are now nonpartisan,” says Marcie Armstrong, who first got involved in politics in 2016 as a Bernie Sanders supporter. Since then, Armstrong has become increasingly angry at the legendary Nevada political machine set up by the late Senator Harry Reid, as party stalwarts worked to contain the insurgents affiliated with Sanders—many of them members of the Democratic Socialists of America—and to push back against progressive policy proposals. After Sanders won the state caucus in 2020, DSA members like Armstrong went all-in on capturing the Democrats’ party apparatus in Nevada; the next year, during elections for party positions, the DSA took over the state party. Armstrong became a member of the Clark County Democratic Party’s central committee. Another Sanders volunteer, Judith Whitmer, became chair of the state party. The new leaders railed against “corporate” politicians and hoped that alone would generate momentum. But they lacked connections to elected officials and fundraisers—and the mass resignation of party staffers in the wake of their takeover didn’t help, nor did the decision by the party’s elders to relocate its fundraising apparatus to the Washoe County Democratic headquarters in Reno. And once in positions of power at the party level, the new leadership proved overwhelmingly inept, unable to deliver on even their most basic promises or to organize local political campaigns and get-out-the-vote efforts. Fed up with this parade of incompetence, party members voted out all the DSA officials, from Whitmer on down, in March 2023, returning control of the party to the determinedly moderate Harry Reid machine.

In the aftermath of the DSA-backed leadership’s implosion, Armstrong now feels politically homeless. “We thought maybe there could be effective change, and it didn’t happen,” she says. “A lot of people are disgusted and don’t want to be involved anymore. They’re either not voting or they say they aren’t Democrats.”

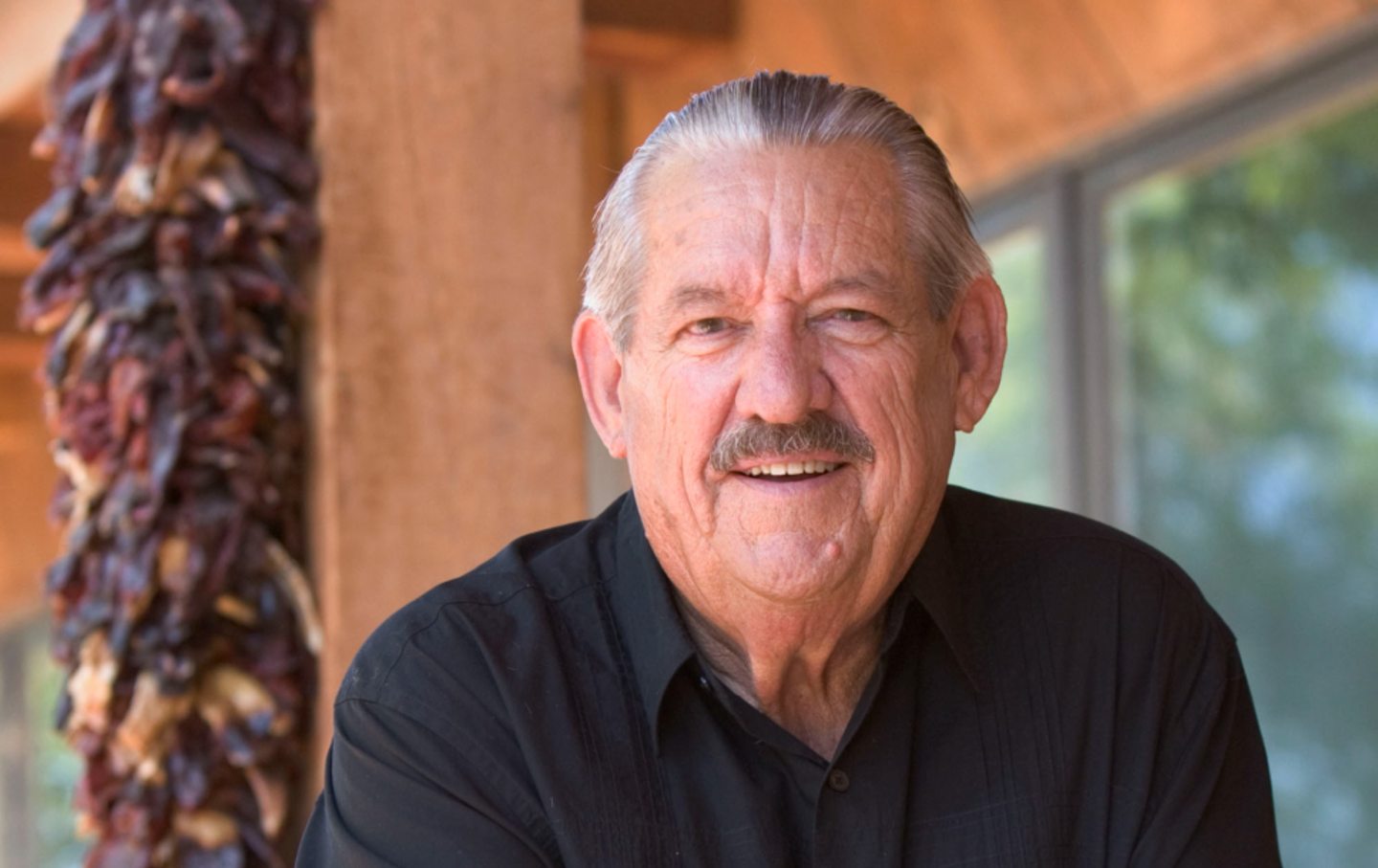

The residue of energy-sapping bitterness from the party’s internal feuding, combined with a more general sense of alienation from the top of the ticket, contributed to the defeat of Nevada’s Democratic governor, Steve Sisolak, by Joe Lombardo, a former sheriff, in 2022. Sisolak was blamed by many Nevadans for shuttering the Strip at the start of the pandemic—which led to a spike in the unemployment rate to an eye-popping, and nation-topping, 29.5 percent a month later—and for the subsequent extreme slowdown of the mainframe computers used in the state’s antiquated unemployment insurance system. By April 2020, the Strip was seeing miles-long lines of cars snaking slowly toward the food pantries that the Culinary Workers Union Local 226 and other groups were operating to feed Las Vegas’s suddenly immiserated masses. “When the Strip went dark, it was scary,” says Ronald Gladstone, a 58-year-old African American kitchen steward at the D Las Vegas Casino Hotel, who has been a Culinary Union member for more than 40 years. “It was like a movie apocalypse. No one around. It used to be bustling. It was kind of eerie. There were no guests. It was weird.”

Sisolak never recovered his political footing.

Despite all the talk of a red wave swamping the country in 2022, Nevada was the only state whose Democratic governor lost to a Republican challenger that year. It wasn’t that Nevadans had suddenly taken a massive turn to the right: Both houses of the state Legislature, including the majority-female Assembly, remained overwhelmingly Democratic, as did Las Vegas’s city government and the Clark County Commission. Three of the state’s four members of Congress are Democrats, as are both of its US senators; a solid majority of Nevadans are pro-choice, rejecting the anti-abortion extremism pushed by many in the GOP; and the state’s electorate seems likely to pass a ranked-choice voting initiative this November. Instead, Sisolak lost his reelection bid because the voters didn’t like him and were willing to take a chance on a smooth-talking, tough-sounding Republican who, they believed, would be hemmed in by the progressive Legislature, even though Lombardo had promised to exercise his veto power against spending bills he didn’t like and affordable housing bills opposed by landlords, and as a tool in the escalating culture wars that were consuming the country. Sisolak’s loss should have been taken as a flashing red light, a warning to Democrats of what could happen in the coming presidential election—with Nevada’s six potentially crucial Electoral College votes at stake—if Biden doesn’t find a way to close the enthusiasm gap and jazz voters up about his policies and his personality.

Four years on from the pandemic’s outbreak, Sin City is booming once more, with new marquee hotels opening, sports franchises moving in, and unemployment down to just over 5 percent—higher than the national average, to be sure, but far lower than it was in 2020. Tourists from all over the world are partying in Vegas like it’s 2019. On the surface, the rage and fear from the 2020 election and its aftermath has dissipated. Yet the general disillusionment with politics remains, like the dull headache of a low-grade hangover—as does the impulse to favor political leaders who opportunistically denigrate the party poopers in public health departments.

Given that reality, Nevadans could side with the Democrats on a range of issues, vote in legislators who would support such policies, and still kick Biden to the curb. “Honestly, I think age is one of the biggest factors,” says Mario Fitzpatrick, a Reno high school government studies teacher and an organizer with the teachers’ union in Washoe County. “I like Biden’s experience, but I don’t know that he’s the right man for the moment. He was—to bring normalcy back to the presidency—but now you need new, fresh ideas that better reflect where Americans are right now. You’ve got to have a president who has that energy—making his face seen, being the face of the US to the public.”

Partly because of the state’s motor voter law—which automatically registers people to vote when they get a driver’s license and which defaults their registration to “nonpartisan” if they don’t explicitly choose a party—but also partly because of anger at the two main parties, independent voters have come to outnumber both registered Republicans and Democrats in Nevada. As a result, the Democratic Party’s once-commanding lead in the number of registered voters has largely evaporated, making it that much harder to know which doors to knock on during the run-up to Election Day. By late 2023, Democrats had only a three-point advantage statewide over Republicans. In Clark County, which includes Las Vegas, the liberal union town crucial to Democratic victories in the state, a onetime double-digit lead is now down to less than 8.5 percentage points, and there was a significant uptick in GOP voter registrations in Clark County in late 2023. In Washoe County in the north, which is usually seen as the state’s key swing county, Robert Beadles, a far-right transplant from California, has been using his financial clout to promote an extremist MAGA agenda, to shape a narrative that Biden’s presidency has been one policy failure after another, and to fund a number of hard-right political candidates. Large numbers of MAGA loyalists there have been showing up regularly at County Commission meetings to push for policies that include placing National Guard members at polling stations and banning LGBTQ-themed books from libraries.

They’re riding a wave of discontent with the current administration in D.C., according to one GOP strategist, who asked to remain anonymous. “Biden’s is a chaos presidency because of the Afghan withdrawal, wars, inflation, the open border,” he says. Last year, the strategist gave the edge to Biden when it came to any rematch with Trump. But by early 2024, as much of the public soured on Biden’s leadership, he was increasingly coming to believe that Trump could take the state “in a squeaker. Biden has to work out a way to turn out the youth vote,” he says. “Without that, it’s just a death sentence for him. Trump voters are excited; Biden voters are not. You don’t need a big ground game to push out [the vote] when people are excited.”

Despite the energy in Trumpland, however, Nevada opinion pollsters and longtime observers of its politics tend to argue that the state, which went for the Democratic candidate in the past four elections, is still Biden’s to lose. They’re deeply suspicious of the early polls showing Trump considerably ahead and believe that Nevada, with its growing number of independent voters, has become increasingly difficult to poll accurately. Union organizing efforts in the Las Vegas area—the Culinary Workers, aware of the notoriously anti-union positions that Trump has taken over the years, knocked on more than 1 million doors statewide in 2022 and are likely to launch a similarly impressive effort this year—may still give the Democrats an edge as the election nears. “We knocked on the doors of over half the Black and over half the Latinx and over one-third of Asian voters” in the state in 2022, says Bethany Khan, a spokesperson for Local 226. In 2024, fresh off its successful negotiations with the largest casino-owning companies—which resulted in a new contract that increases workers’ starting pay and benefits from $28 to $37 an hour over the next five years—the union plans to lead the largest field effort in the state, Khan says.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

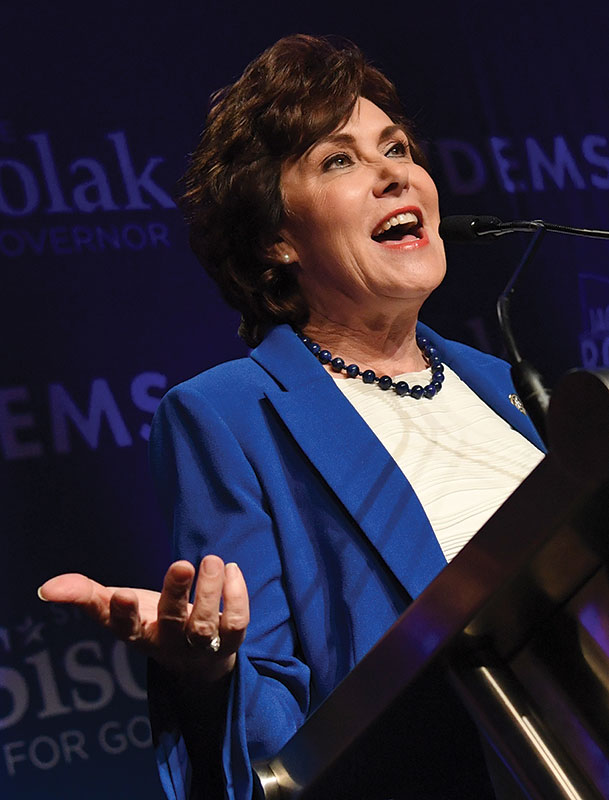

The Harry Reid machine, which counts the large unions as key components, may have been damaged by the battle with the DSA for control of the Democratic Party. But seasoned political observers argue that it remains a powerhouse in the state’s perennially close elections, much as it was in 1998, when, against the odds, Reid eked out a reelection victory by a mere 428 votes. Twenty years later, in 2018, Senator Jacky Rosen’s victory margin was much larger than that, though still relatively small at roughly 50,000 votes. But the result was a clear victory for the Democrats and a clear sign of the durability of the Reid machine. Senator Catherine Cortez Masto’s squeaker of a reelection in 2022 showed that, even after Reid’s death a year earlier, it remained a force to be reckoned with. “We delivered the state for Cortez Masto—by a small margin, but we got her through,” Khan says. Nevada political observers expect that machine to come out in full force for Rosen and her reelection campaign this year.

Moreover, the state has made it far more difficult for individuals and movements to harass election workers or to push election-denialist propaganda; in May 2023, at the urging of Secretary of State Cisco Aguilar, the Legislature passed, and Governor Lombardo signed, a bipartisan Election Worker Protection Bill that increases penalties for harassing election workers and makes it harder for candidates to gin up plots such as the 2020 “false electors” conspiracy.

Observers also point to the confusion generated by the Republican Party’s decision to hold a presidential caucus to allocate its delegates, even after the Democratic-controlled Legislature mandated that Nevadans be offered a primary. The GOP insisted that its candidates could be in either the caucus or the primary but not both—and then, since caucuses are easier to close off to nonpartisan voters, it insisted that only the caucus results would count in the allocation of delegates. But many Republican voters—some of whom took to social media to declare that the absence of Trump’s name from the primary ballot was yet another example of the deep state conspiracy against their MAGA leader—simply ended up confused. Former South Carolina governor Nikki Haley, who is challenging Trump for the nomination but knew she couldn’t beat him in a caucus tailored to his strengths, made the strategic decision to sacrifice delegates by running as the highest-profile candidate in the primary, which she lost to the ballot option for “None of these candidates.”

The Nevada Republicans’ dysfunction may not sit well with general-election voters heading into November. Neither will the fact that state GOP chair Michael McDonald was indicted in late 2023 on felony charges relating to his being a false elector after the 2020 election. The adoption of universal mail-in ballots, as well as the passage of recent legislation allowing tribes to request polling places situated on their land, promises to raise political participation in a direction that tends to benefit the Democratic Party.

“It’s way too early to make any judgments on any of this stuff,” says Jon Ralston, the CEO and editor of The Nevada Independent. “We’re a purple state, and the presidential race is close here.” But Ralston thinks that the Democrats’ margin of error has gone way down over the past few years. “The bottom line is, a lot of people think their messaging has not been great, and the term ‘Bidenomics’ has not been resonating with people,” he says.

Despite the public statements of optimism from Democratic Party leaders, and despite the ramped-up grassroots efforts by organizers with Local 226 and other unions, there is a clear sense of unease below the surface. Ralston says that Democrats are concerned about Biden’s low approval ratings, as well as his hemorrhaging of support among young people and Latinos, the latter of whom make up 20 percent of the state’s voters. Trump’s team has been aggressively courting those voters in recent months—some national polls show Trump beating Biden among Latino voters, while a November poll of Latino voters in Nevada shows Biden still leading among that group, but by a far smaller margin than he commanded in 2020.

“We have a lot of work to do,” says Tim Cox, a Clark County Democratic Party activist and onetime candidate for the Henderson City Council. He worries that the party, still recovering from its two years of infighting, isn’t as focused on getting out its voters come November as it needs to be. Cox, an adrenaline junkie who skydives dozens of times a year and regularly jumps off Las Vegas Boulevard’s 1,149-foot-high Stratosphere, doesn’t scare easily, but he says he is scared by what could happen in November. “People are disengaged,” he says. Even though Las Vegas is thriving again, there’s a lingering anger at the massive economic dislocation caused by the pandemic public health response—and, he says, many people he knows who opposed it are going to vote for Trump as the face of opposition to lockdown mandates.

By most measures, Nevada these days is a blue state. Most of its senior elected officials, with the exception of the governor, are Democrats, and the party’s supermajority in the Assembly, combined with its near-supermajority in the Senate, has allowed it to push a raft of progressive reforms, from increased education spending to investments in electric vehicle infrastructure. A majority of Nevada’s population, propelled by liberal voting blocs in Las Vegas and Reno, is firmly on the side of reproductive rights. Las Vegas has embraced some of the country’s most innovative environmental sustainability policies, and demographically the city, which now has more residents than Boston, is increasingly diverse.

“What I’m feeling and seeing now is, healthcare is still on the table. Women’s access to healthcare and reproductive freedoms is still on the table,” says Democratic Assemblymember Shea Backus, whose Las Vegas district is one of the swing districts that Governor Lombardo and the Republicans have targeted this election cycle. “The other thing is, people are very concerned about democracy in America.” Backus argues that with his extensive use of the veto, Lombardo has put himself on the wrong side of a number of issues, including affordable housing, that are dear to her constituents’ hearts.

Backus’s colleague Selena La Rue Hatch, who represents a swing district in Washoe County, agrees. A 34-year-old high school world history teacher, La Rue Hatch thrives in her on-the-doorstep meetings with constituents. They talk to her about soaring housing prices, the environment, and abortion. “That’s a huge issue,” she says, sitting on a stool in a suburban Starbucks in Reno. “Even across party lines.”

Yet every state has its individual political quirks, and despite wariness about the GOP’s rightward lurch, Nevada’s is a penchant for divided government. Over the past generation, it hasn’t been uncommon for Nevadans to divvy up political power between the parties—balancing the Democrats’ growing legislative clout by electing a series of Republican governors, who exercise much of their power by wielding the veto pen against Democratic measures (and, since the Legislature meets for only a few months every other year, by governing via executive orders when the Senate and the Assembly are not in session).

Steve Sisolak’s election in 2018, which gave Democrats the trifecta of power in the state, was an exception—part of the backlash triggered by Trump’s shock presidential victory in 2016. Sisolak’s defeat by Lombardo four years later simply restored, in a sense, the balance that Nevadans have historically tended to favor. It also showed both the Democratic Party and its on-the-ground union allies just how hard they will need to work to deliver the state to Biden in November.

Bethany Khan, of the Culinary Workers Union, isn’t worried. Over a lunch of tomato soup, steak, and french fries at a bistro training academy run by the union to bring new workers from the impoverished west and north sides of Las Vegas into the high-wage casino economy, she explains, “It’s an organizing challenge, and we’re one of the best. We’ll meet it head-on—workers talking to workers.”

Come this autumn, hundreds of those union workers, like 36-year-old Satoria Partridge, a Circa Resort & Casino porter and mother of three, will take a leave of absence to join the canvassing teams, hoping to once again tip the state into the blue column on Election Day. They will be talking about everything from reproductive rights to rent control, from how to treat immigrants with respect to how to ensure well-paying jobs for the next generation of Las Vegas workers. For Partridge, it’s a simple equation. “I’m a union baby,” she says. “The Biden administration is very pro-union.”

Partridge’s optimism may win out. After all, the Harry Reid machine—resurrected after its brief toppling by the DSA—has a storied history of snatching narrow victories from the jaws of defeat. But the Democrats would be fooling themselves if they didn’t think they had a brutal fight on their hands in the Silver State.

More from The Nation

Enough With the Bad Election Takes! Enough With the Bad Election Takes!

To properly diagnose what went wrong, we need to look at the actual number of votes cast.

No, Kamala Harris Staffers Did Not Run a “Flawless” Campaign No, Kamala Harris Staffers Did Not Run a “Flawless” Campaign

Democratic strategists are still patting themselves on the back for a catastrophic defeat.

The Courts, Trump, and Us: A Q&A With David Cole The Courts, Trump, and Us: A Q&A With David Cole

Last time, the courts were an essential checking force on the Trump administration. This time around, they may again provide a check—if we push.

Congresswoman Barbara Lee on Why Shirley Chisholm Was Right Congresswoman Barbara Lee on Why Shirley Chisholm Was Right

The California Democrat explains why, during her 25 years in Congress, it was important for her “to disrupt and dismantle and build something that’s equitable and just and right.”...