Marianne’s People

To her detractors, presidential candidate Marianne Williamson is a political joke. But for her most fervent supporters, it is, as one of them put it, “Marianne or death.”

“It’s Marianne or Death”: On the Campaign Trail With Marianne Williamson

To her detractors, presidential candidate Marianne Williamson is a political joke. But for her most fervent supporters, she’s their only hope.

Marianne Williamson is surrounded by her people. They cling to her every word. No one pulls a phone out in the middle of her speech. They sit rapt, a few dozen of them, as she paces around in her powder-blue suit, making eye contact with as many individuals as she can.

It’s a Saturday afternoon in early September, and Williamson is at Nandi’s Knowledge Cafe in Highland Park, Mich., a 9,000-person town that’s almost completely encircled by Detroit. Though residents here are quick to point out this isn’t Detroit, there are a few similarities: It’s majority-Black and has suffered from a systematic lack of investment. It’s had highways rammed through it and seen factory jobs disappear. Recently, the Highland Park government told the state it could no longer afford to keep its water running.

Nandi’s is the kind of place that tries to be an antidote to all that. Proud and radical and hopeful. It’s stocked with books about Black liberation and healthy eating and decorated with the flags of African countries—and, today, a bunch of “Marianne Williamson for President” posters.

It may be surprising that a place like this is where Williamson’s stump speech lands best, given that she rose to prominence not as a political radical but as an author of self-help books and as one of Oprah Winfrey’s spiritual gurus. But once you hear the speech, it makes a certain sense. In her way, Williamson is communicating something similar to what Nandi’s is all about: hope. Hope that things can change despite how bleak everything is—despite the houses falling down outside and the traffic lights without light bulbs and the history of racism and community destruction that got us here.

Many people have asked why Williamson is the one to convey this hope. She has no experience as an elected politician; she has consistently polled under 15 percent with Democratic voters; and many, including former campaign staffers, have questioned whether she cares more about her ego, or her book sales, than she does about actually transforming the country. Williamson has rejected those accusations. She insists on a different explanation: because there’s no one else.

“I know a lot of people in the world today, in America today, particularly our young people, are feeling very helpless,” Williamson says as she takes the mic. “And I think one of the reasons I’m running for president is because that’s really dangerous. Too many people are spiraling down.”

She says that people feel more hopeless now than they did when the Vietnam War was raging and movement leaders were being assassinated year after year. But, she says, that lack of hope is not our fault. Those who want to change the world are often told that change is impossible. Suffragists. Abolitionists. Labor organizers. Her. And that’s the problem today: We’ve all internalized this hopelessness. Her pitch for why the world can change is the same as her pitch for why she can win: It’s about faith. We just have to have faith that what we’ve been taught is impossible is in fact not.

“The people of the United States are not the problem,” she says, her voice rising, but also a bit hoarse and raspy. “The problem is that the people of the United States are tyrannized today. Tyrannized by a matrix of corporate power, from insurance companies to pharmaceutical companies, to big food companies, to big agricultural companies, to chemical companies, to gun manufacturers, to Big Oil, to defense contractors, to banks.”

Her speech is both wide-ranging and specific. She talks about her plan for reparations for African Americans; about how Democrats have failed their constituents; about the need for a strong labor movement, for an economic Bill of Rights, for universal healthcare, for the elimination of college debt, the elimination of the prison-industrial complex, the elimination of the War on Drugs.

There are a lot of applause lines, but it becomes clear to me later, after interviewing some of her supporters, that what really draws people to Marianne, as many of them call her, is not so much the specifics of her policy proposals (though they say those are important), but her particular theory of how we make change—that we must first believe we can transform internally before we can affect anything else. It’s a message steeped in the New Age self-help speak that has been her vernacular since at least the 1990s—when she wrote her first, breakthrough book, A Return to Love—and it’s been the through line of her career. It’s just the specifics of what, exactly, we can change once we begin believing in ourselves that have shifted. Whether, as she discusses in her best-selling book A Course in Weight Loss: 21 Spiritual Lessons for Surrendering Your Weight Forever, it’s our bodies and self-image, or whether it’s our relationships to our loved ones and the world (the subject of A Return to Love), or whether it’s the very nature of American capitalism, the mechanism is always the same: First, we must believe in our individual power.

There are politicians whose politics are similar to hers, perhaps most obviously Bernie Sanders, who, like Williamson, ran for president in 2020 espousing a critique of America as a fundamentally unfair society in need of massive, systemic change. What makes Williamson singular is not her politics, but how those politics are conveyed. And that’s where most of the support for and criticism of Williamson seems to come from. To her detractors, she’s a New Age self-help guru more than a politician. To her supporters, she’s… a New Age self-help guru more than a politician. And that’s what they love about her.

The question now is—and really always has been—whether Williamson’s skills as a speaker or spiritual leader can be effective at more than just inspiring her followers. To win in politics, to actually change the world, you need a movement, a critical mass of people. As I trailed Williamson through Michigan, as people teared up and thanked her for helping them in their personal lives, that question hung in the air: Could she convert support for her as a person, a personality, into support for something, anything, larger?

For Ellebeah (pronounced “LB”), the woman who introduced Williamson at Nandi’s, the possibility of internal transformation is what drew her to Williamson long before Williamson was involved in politics. ElleBeah was born and raised in Detroit. She went to Cass Tech, a prestigious Detroit magnet high school. Then she got pregnant. She married the father, her best friend. He joined the Navy, and she followed him to New England, where in 1992, after having three children, she divorced him.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →“Here I am, a Black woman, now divorced, with three children and a high school education,” ElleBeah says. “I felt worthless.”

In her quest to pick up the pieces of her life, she read a recently published book by Williamson called A Woman’s Worth. ElleBeah credits it with turning her life around. “When the world was saying I was worthless, Marianne was saying, ‘No, no, no. Who are you not to be brilliant, gorgeous, talented, fabulous?’” she recalls.

ElleBeah read more of Williamson’s work. She went to college and graduated cum laude. She got a job in academic advising, because she had a penchant for helping students home in on their life’s purpose. And then she earned a master’s degree in holistic counseling; she wanted to be like Williamson and her two other “sheroes”—the inspirational speaker Iyanla Vanzant and the poet Maya Angelou.

“Now I get to do what Marianne did for me,” ElleBeah says. “Empower people. Help them to reconnect with their inner worth.”

ElleBeah returned to the Detroit area, to a suburb called Walled Lake, about 17 years ago. She followed progressive politics but became disillusioned with the Democratic Party in 2016, when it seemed as if the Democratic National Committee was doing everything in its power to stop the nomination of Sanders. And then she saw that Williamson was running as a Democrat in the primaries for the 2020 presidential election.

“I talked to my TV screen,” ElleBeah told me. “I said, ‘Listen, Marianne, you don’t know me, but I’ve got your back.’” And so she volunteered for Williamson’s campaign.

In 2019, Williamson’s strong statements on the debate stage in support of reparations, as well as her use of the phrase “dark psychic force” to describe the racism embodied by people like Donald Trump, grabbed the attention of many. But that buzz never translated into votes, and Williamson ended her campaign in January 2020.

Six months later, one week before Father’s Day, ElleBeah’s father died from complications during his treatment for Covid. ElleBeah had gotten Williamson’s personal number in 2020 (Williamson is very liberal with her telephone number and texts dozens of people every day, including me while I was writing this story), and so ElleBeah called her. ElleBeah said she feared she wouldn’t make it. That she might jump off a building from the stress and grief. Marianne told her she wouldn’t. That she had spiritual maturity. That Marianne wished that her daddy was with her all the time too, but that he still is, in a different way. And, ElleBeah says, “she was right.”

With all that in mind, ElleBeah volunteered again when Williamson announced her 2024 run. Williamson’s polling has been a bit better this time. But it seems to many like a foregone conclusion that Joe Biden will win the nomination: There are no scheduled debates, and the media has mostly written Williamson off as a fringe candidate. To her supporters, that’s all the more reason to work for her. They believe it’s not that she doesn’t have a chance; it’s that forces like the DNC and the media establishment are so scared of what she represents that they will do everything in their power to make sure people think she doesn’t have a chance.

Whether that’s true is up for debate. Sanders, for example, came a lot closer to winning a presidential election than Williamson ever has. In the lead-up to 2020, he drew tens of thousands to his rallies.

But Sanders isn’t running this time. For some, Williamson is the only hope—and they remain fervently committed to her.

At the end of the day, ElleBeah says, “I feel it’s Marianne or death.”

After Nandi’s, I meet Williamson in the lobby of the Marriott where she and her campaign manager are staying, in a part of suburban Detroit that looks like every other place where Marriotts thrive—highways and corporate parks and Chipotles and such. We sit in the nearly empty hotel restaurant, where she orders a bacon-and-potato soup and an Arnold Palmer.

Williamson, who’s 71, is intense. When she talks, she stares into your eyes and gets close to your face. It’s partly her personality, like she really wants you to know she’s listening, and partly because she’s a bit hard of hearing and wears hearing aids.

She has another campaign stop, in another Detroit suburb, at another café—this time in a more affluent part of town—in a few hours. She seems both wired and tired, perhaps amped up from the stump speech. She also has a slight cough. She’s been on the campaign trail for a long time, working to get her message out despite a small campaign staff and quickly dwindling funds, which have included more than $200,000 of her own money. To her, the campaign’s difficulties are a sign that the powers that be are scared of her and her message.

“I’ve been invisibilized. Trivialized. Smeared. Minimized,” she tells me. “We know what’s going on…. I’m pointing to the ravages of neoliberalism in this country. I’m calling out the malfeasance of trickle-down [economics]. I’m saying the deeper problem is not Donald Trump but corporate greed. I’m saying the things you’re not supposed to say out loud.”

As Williamson sees it, her message is proved by her struggle to gain traction—evidence that the system will ignore or dismiss anyone who is a threat. That’s why, she says, many media reports won’t even mention her campaign; that’s why she’s not on Meet the Press, even though Republican candidates who routinely poll lower than she does are. She says that when she has a more direct relationship with Americans, she breaks through. Videos of her speeches regularly go viral on TikTok, and one analysis found that she had more support on that platform than any other candidate, including Biden. That could explain why, digging into the polling data’s cross tabs, you’ll find that her support is much higher among young people: 27 percent of 18-to-29-year-olds would vote for her, according to an August 2023 New York Times poll.

In her stump speeches, Williamson focuses mostly on policy, but one-on-one, it becomes obvious that she is preoccupied with her lack of mainstream acceptance. It comes up again and again as we talk.

“Sometimes I feel there’s an irrational animus against me,” she says. Even the people who support the causes she supports tend to dismiss her, which has left her feeling angry at people on the left. “All that solidarity talk,” she says. “In my case, it’s solidarity my ass!”

That’s why, I think, Williamson is eager to be in Detroit, to be on home turf, to talk to people directly—not only so they can hear her, but so she can hear directly from them, the people who think she’s the one.

The optics, the horse race—“none of that mattered,” she says, “to the people today at Nandi’s.”

It’s time for more events. Williamson is whisked around in a Mazda by an old friend, Dennis Mazurek, a local attorney who met her 25 years ago, when she lived in the Detroit area. He takes her to the Fern, a café in Royal Oak, where Williamson delivers a stump speech similar to the one at Nandi’s.

The audience here, about 70 people, is different—mostly white, lots of flannel shirts. But the message hits them the same, despite Williamson’s increasingly raspy voice and cough. They applaud the reparations lines and the Democrats-are-garbage lines as much as the lines about how people should have access to non–Big Pharma treatments when they get sick. One attendee, a 28-year-old barista named Lunar Klein, lines up with about two dozen others to meet Williamson after her talk.

Later, Lunar tells me they don’t trust the country to do the right thing anymore. They’re trans, as is their girlfriend, and both have looked into moving to Canada if Trump or someone like Ron DeSantis gets elected. They first came across Williamson on TikTok and then saw an interview with her and Hasan Piker, the popular leftist Twitch streamer. They liked how she talked about corporations and union-busting, and said that Williamson can’t solve everything on her own but wants to put young people on a path so they can continue working to change the country.

But after Israel’s bombing of Gaza, Lunar had a change of heart: Williamson’s statements on Gaza have been contradictory and middle-of-the-road. For Lunar, that meant they could no longer support her.

“To be honest, I’ve stopped really paying attention to what Marianne has been saying about anything lately due to being disgusted with her,” Lunar texts me. “But I just checked her Instagram and it seems like she’s being pretty quiet about it now. Silence is violence. And it’s too little too late now.”

The next morning in Michigan, Williamson is driven out to Ann Arbor to give a speech at a spiritual center, which is packed—and then to an Italian restaurant in a strip mall, where a private room has been reserved and a very surprised waiter, who calls Williamson “a gay icon,” ushers her in to meet five women for lunch.

It’s here that I meet Toni Bunton. She, like many women here, was once incarcerated in a Michigan prison. Williamson has been working on her criminal justice platform; this is her second meeting in two days with people impacted by mass incarceration. Over salads and pasta, the women tell Williamson their stories. Each story is horrific, the prosecutions unjust, the conditions in prison criminal. A stark reminder of the stakes of politics in this country: It’s real people who live and die by the choices our politicians make. Some of the women tear up. Bunton reassures them that their post-prison lives will get better: “The Lord will restore to you all the things the locust has eaten.”

Bunton, who’s 49, is a criminal justice reform advocate, a social worker, and a mom. She’d seen Williamson on Oprah several times and had read one of her books. One day in 2000, Williamson walked into the Robert Scott Correctional Facility, where Bunton was serving 25 to 50 years. She’d been charged with second-degree murder for driving the getaway car for her then-boyfriend, who, in the midst of a drug deal gone wrong, had murdered someone. Bunton’s prison experience was horrible—sexual assault, fights. She wanted to die.

The first time Williamson visited the prison, Bunton had a chance to talk to her one-on-one. That’s when Williamson quoted a Bible passage to her about God restoring the things the locust had eaten. The way Williamson said it—looking into Bunton’s eyes—had felt deeply spiritual.

“When she said that, I believed her,” Bunton says. “And something inside me changed at that point.” Williamson returned to the prison again and again. Each time she spoke, she would give Bunton hope that things could change. “I really believed everything she said,” Bunton tells me. “I still believe that she is carrying a message for something bigger than us. I’m not saying that she’s Jesus or anything. Clearly, she’s a human being, but I think that her message is very powerful.”

After Bunton spent 17 years in prison, her sentence was commuted by then-Governor Jennifer Granholm. Now, as a social worker, Bunton sees a country in crisis—people can’t pay their bills; they feel completely alone and hopeless. Which is why, after all these years, she’s still a big supporter of Williamson. Whether Williamson can win is a different question.

“Do I think [her] running for president is a waste of time is basically what you’re asking me, right?” Bunton says, and then laughs nervously. “Um, you know, I don’t know how to answer that, because I want to be sensitive to Marianne.”

But, she adds, people laughed at Trump too, and then he won.

Williamson moved to Michigan in 1998, to lead what was then known as the Church of Today, a congregation affiliated with the New Age–y Christian sect called New Thought. By the time she became its lead minister, the church had around 1,000 members. Williamson drew in at least 1,000 more; eventually, the church was renamed Renaissance Unity, and Williamson dubbed herself a “spiritual leader” to make it feel less denominational. (Williamson, who’s Jewish, believes that spiritually, there is “one truth spoken in many different ways,” she says.)

Williamson would bring in famous acquaintances from Los Angeles—Steven Tyler from Aerosmith, the singer Jewel. But according to Dennis Mazurek, what really attracted people was Williamson’s uplifting message. That message was often based on Helen Schucman’s popular and controversial spiritual book A Course in Miracles, which since its publication in 1976 has been promoted by several New Age gurus and celebrities; it was described by Psychology Today as part of the “supermarket of cults, religions and psycho-mystical movements.”

Williamson says she helped diversify the church racially and spiritually. “When I came there, it was very white-bread, mainly Republican,” she says. “I started talking about racial equality. All of a sudden, you had 3,500 people on a Sunday morning.”

In 2002, Williamson suddenly stepped down. The circumstances surrounding her departure are disputed. According to Williamson and some of her former congregants, it’s because she began bringing a more radical political message to the church and focusing on things like racial equality, which did not jibe with some of the church’s more conservative board members. But at the time, some accused her of not managing the church’s membership or finances well and then quitting preemptively to avoid getting fired.

Williamson moved back to California and focused on her career as an author and speaker. Over the years, she became more politically inclined. After her bestseller A Return to Love, she wrote Healing the Soul of America, in which she began to embrace what has become her core political message: the belief that large-scale societal change has to start within each individual.

The first time Williamson ran for office, in 2014, was as an independent in California’s 33rd Congressional District. She told Bloomberg News at the time that she believed everyone on earth had a “special function,” and that hers was to run for Congress. She came in fourth.

Back at the hotel, Williamson tells me she is in Michigan because it’s an important primary state—especially now that the Legislature has moved the primary to February. It’s important to focus her campaign’s limited resources here, Williamson says, as well as in New Hampshire and Nevada. But by all objective measures, her bid is a long shot, no matter how much hope Williamson injects into it.

Some former staffers of Williamson’s campaign have accused her, all but one anonymously, of being a toxic and at times abusive boss, and they have also charged her campaign with having no strategy to win. “There is no plan for obtaining ballot access or securing delegates,” some former staffers wrote in a letter published in August. Williamson has denied all these claims, but accusations that she is an excessively tough boss have followed her for decades. She jokingly referred to herself as a “bitch for God” in a 1992 profile in People magazine.

The contrast between what so many who surround her say—that she has saved or changed or markedly improved their lives—and these allegations might not make sense until you sit down with her.

I tell Williamson that perhaps part of the reason it’s hard for her, or anyone to the left of Biden, to gain traction is that most of America—certainly most of the people I know—feel hopeless, particularly about the usefulness of electoral politics. And that’s when I think I see a glimpse of the other side of her. Not abusive, but certainly tough.

“I wanna say, ‘Toughen up, buttercups—boo hoo,’” she replies. “You think it wasn’t hard for the abolitionists? You think they got what they wanted in just a couple of election cycles? Do you think it wasn’t hard for the women suffragettes who were thrown in prison for the crime of marching for suffrage? Don’t you think they were a little traumatized and anxious? You think the people who walked across the bridge at Selma weren’t scared? We are too soft for this revolution.”

Williamson is now drinking hot tea—her voice is hoarser, her cough worse. She tells me we spend too much time invested in our own weaknesses, our own grief.

“You have to give yourself the hour to cry, and then at a certain point you gotta take a shower and get out there,” she says. “There’s a lot of hours in the day.”

When she was growing up, she continues, people would read Ram Dass and Alan Watts in the morning and then go to an anti–Vietnam War protest in the afternoon. You have to learn how to do both, she says. Martin Luther King Jr. understood this too, she says—that for politics to shift, we needed, to quote MLK, “a qualitative change in our souls as well as a quantitative change in our lives.” Williamson seemed keen to connect her campaign, and herself, to that period—to the idea that those on the right side of history had to constantly fight against the mainstream, and that she is the latest in a long line of leaders to do so.

But we don’t live in that period. Williamson is not Martin Luther King Jr., and unlike King, she doesn’t have a mass movement behind her. King’s message and spirituality were part of something large and dangerous to the status quo—so dangerous that his supporters were arrested and beaten and King was assassinated. Williamson and her supporters pose no such threat. But the reason for that depends on whom you ask: Is it because, at the end of the day, Williamson is still who she always was—an effective speaker and motivator, but not a threat to the political order? Or is it, as Williamson suggested to me, because the powers that be are determined to prevent anyone else from taking her seriously?

Seeing Williamson in person, hearing her speak to supporters, coherent and passionate, charismatic and intense, talking about systemic racism and class—it can sometimes feel like you’re seeing the real thing. But then you leave Nandi’s or the Fern, and you leave all that too. There’s no march of tens of thousands outside, no politicians on television warning about the army of Williamson supporters. After I leave Michigan, the only times I hear about Williamson are through channels of her own making—Twitter, TikTok, Instagram: a post criticizing the Biden administration’s environmental policy, a post where she passionately argues for free healthcare, a post I see a few days after my trip, where she realizes her raspy voice and cough are actually from a case of Covid.

Whether that lack—of a mass movement, of impact, of press coverage—is an indictment of her as a candidate, or an indictment of everything else (the media, the political apparatus, her supporters), is the question Williamson would have us ask. Is she not the one—or have you not believed in her hard enough yet?

More from The Nation

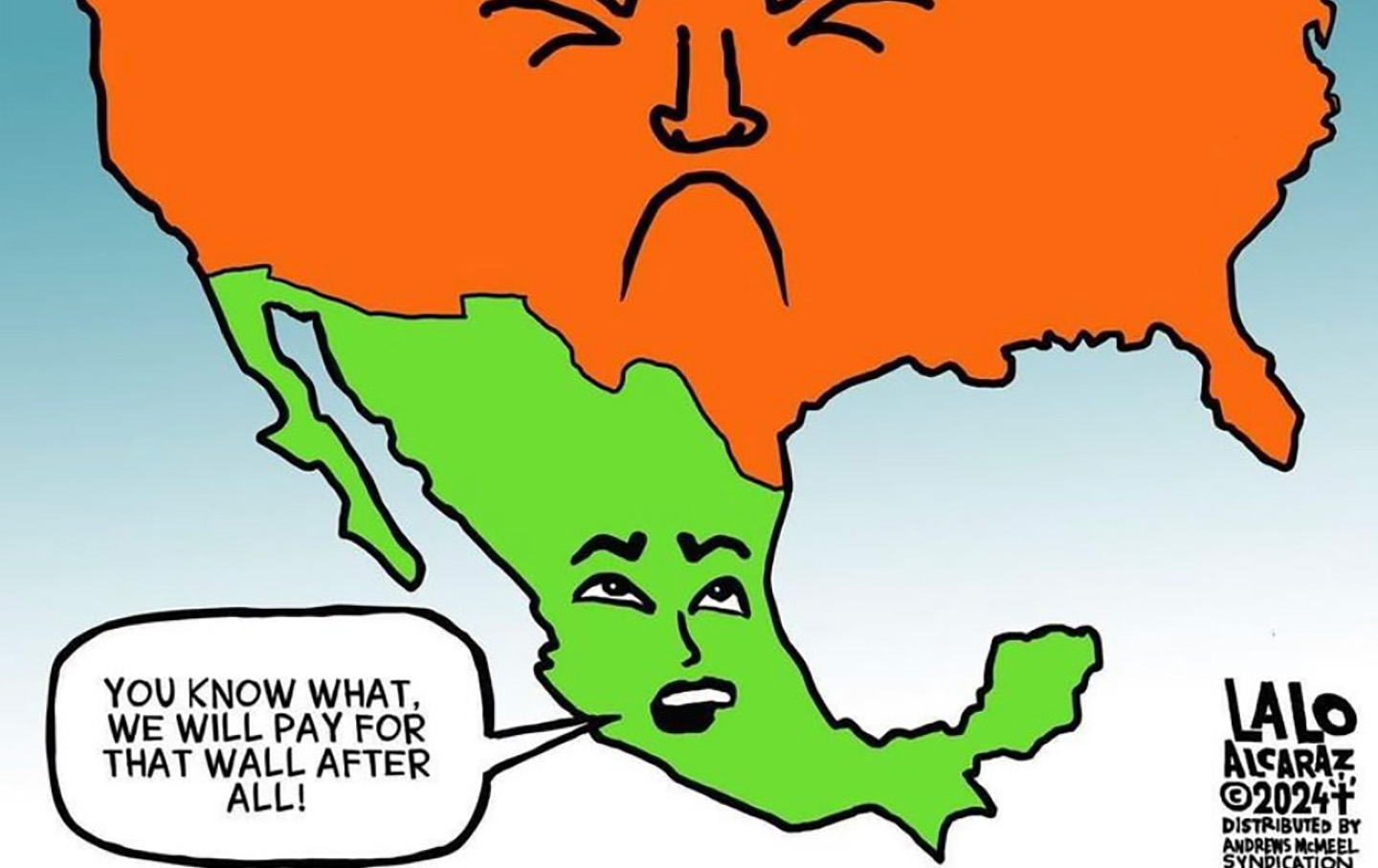

Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk

Far from being an alien interloper, the incoming president draws from homegrown authoritarianism.

If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions

The Democrats blew it with non-union workers in the 2024 election. Unions have a plan to get the party on message.

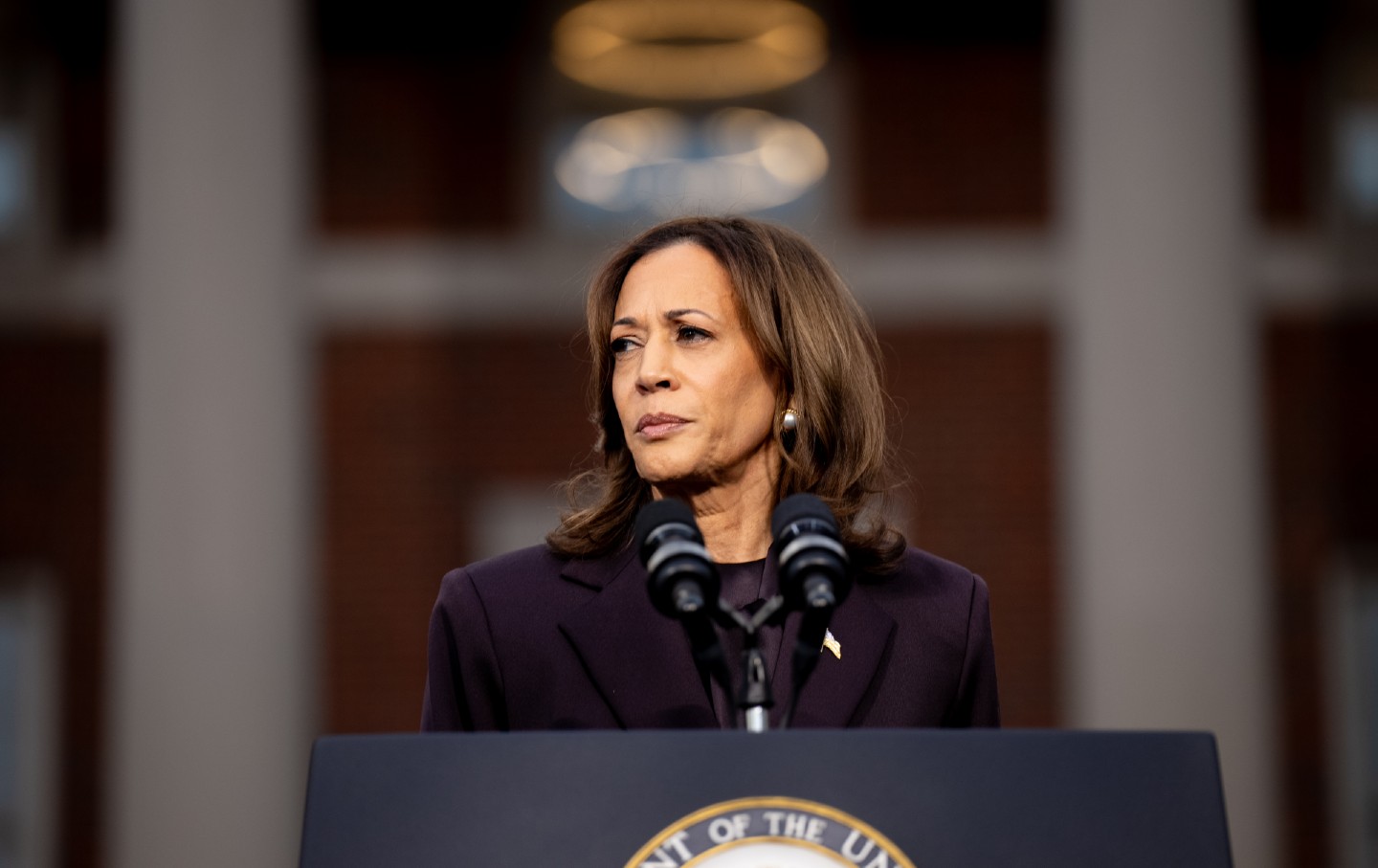

What Was the Biggest Factor in Kamala Harris’s Defeat? What Was the Biggest Factor in Kamala Harris’s Defeat?

As progressives continue to debate the reasons for Harris's loss—it was the economy! it was the bigotry!—Isabella Weber and Elie Mystal duke out their opposing positions.