Too many congressional Democrats are making a potentially fatal political miscalculation about the reason the party lost several seats in this year’s elections. And those incorrect interpretations of why Democrats lost at least 12 seats could lead to grievous missteps that will imperil their majority in 2022.

Representative Sean Maloney, incoming chair of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, has pledged to be data-driven in his quest to improve Democratic prospects in 2022, saying, “If you’re not God, bring data.” Taking him at his word, then, here are the data that have been largely overlooked in the post-election analyses.

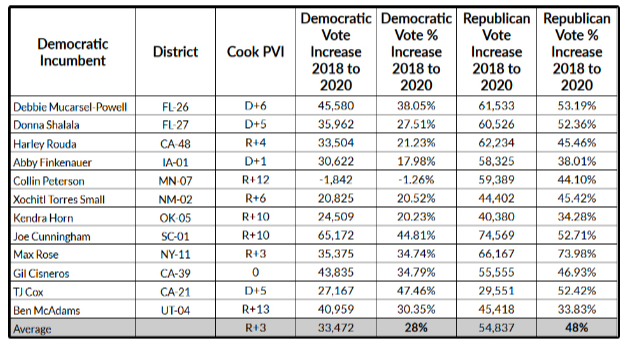

Completely contrary to much current conventional wisdom, House Democrats actually outperformed their prior electoral showings by significant margins—24 percent greater, on average, for the nine incumbents who had lost their seats as of November (the outcomes in several races are still too close to call). The problem was that Republicans outperformed their earlier showings by an even greater margin, boosting their vote totals by 46 percent over 2018.

Several of the Democrats who lost or came close to losing their seats strongly believe that affiliation with progressive calls for social change damaged their contests this year. On a post-election call with party leaders, Representative Abigail Spanberger articulated this point of view when she reportedly blamed the Black Lives Matter demand to “defund the police” and the specter of “socialism” for many of her and her colleagues’ electoral woes.

The truth behind the unexpected losses, however, is exactly the opposite of what those members believe. It wasn’t their proximity to the words that some movement activists use to promote solutions to economic and racial inequality that made their races competitive. It was their failure to inspire progressive and Democratic voters to the same extent that Donald Trump galvanized his supporters to turn out in extraordinarily large numbers to defend him and his race-baiting presidency.

None of the Democratic incumbents who lost their seats lost many, if any, votes from the 2018 totals that put them in office in the first place. On average, the number of votes for Democrats in those districts increased by 33,000. The number of Republican votes, however, increased by an average of 55,000.

In a voter-turnout battle, which is what American politics is now, there are definitely some congressional districts that just don’t have enough Democratic voters to hold those seats in contests where high percentages of the electorate participate. The Republican pickups occurred in districts that are relatively conservative to start with, historically voting four points more Republican than the country as a whole, according to the Cook Political Report’s Partisan Voting Index.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The good news for Democrats is that the pool of potential voters who could be brought into the active electorate has more than enough progressives for them to prevail in most cases, certainly in enough cases to hold majority control of the House of Representatives. This is especially the case in the South and Southwest, which are going through rapid racial demographic changes.

Rep. Donna Shalala’s South Florida district, for example, is two-thirds Latino, and while she prevailed in 2018 by 15,000 votes, 200,000 people in that district didn’t cast a ballot at all. When she stood for reelection this year, an additional 91,000 people voted, but it was failure to match the Republican increase that doomed Shalala, as her 36,000-vote increase was eclipsed by a Trump surge that saw 60,000 more Republican voters cast ballots. It is also notable that in a district with large numbers of non-voting Latinos, Republicans fielded a woman of color, Maria Elvira Salazar, to challenge a white Democrat.

A similar situation unfolded in New Mexico’s Second Congressional District, where Xochitl Torres Small won a close contest two years ago by 4,000 votes. In that race, where the district is nearly half Latino, more than 300,000 people did not vote. This year, Torres boosted her numbers by 21,000 votes, but her Republican opponent, Yvette Herrell, picked up an additional 44,000. There are still nearly a quarter-million eligible people in that New Mexico district who didn’t vote at all. That is the sector of the population that holds the key to Democrats’ future prospects.

For all the attention paid to the Democrats who lost or almost lost, the greatest insights and lessons come from those who won, most importantly in Georgia. In 2018, Carolyn Bourdeaux lost her bid for a greater Atlanta congressional seat by just 417 votes. This year, riding the wave of expanded Democratic and African American turnout propelled by the formidable grassroots progressive electoral operation in that state, Bourdeaux improved on her 2018 showing with an additional 51,000 votes, enabling her to oust incumbent Rob Woodall, despite a Republican gain of 40,000 votes.

Ironically, the numbers in Spanberger’s own race tell the same story of increased Democratic turnout being the key to electoral victory. Spanberger won this year by an even larger number of votes than she did in 2018, despite a massive increase of 53,000 votes by her Republican challenger. Benefiting from the groundwork laid by civic engagement groups such as New Virginia Majority, Spanberger prevailed because 54,000 more people voted for her than in 2018.

If the lesson, then, is that Democratic shortcomings stem more from failing to turn out more of their core supporters than from turning off voters who dislike progressive politics, then they will need to reconfigure their strategic targeting and spending priorities in the coming years. Between them, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, the political arm of the House Democrats, and House Majority PAC, the super PAC focused on boosting Democratic congressional candidates, spent nearly $400 million. Far too much of that money, however, went to television ads trying to persuade a smaller universe of likely voters to vote blue rather than to civic engagement activities and grassroots organizations focused on expanding the overall universe of voters.

The nine Democratic incumbents who lost their seats fell short by an average of 16,000 votes. In those same districts, despite record high turnout, an average of 154,000 eligible voters still didn’t cast ballots. The nonvoting numbers are even higher in Texas, where Republicans held on to eight seats that they were at risk of losing.

Those nonvoters didn’t stay home because Republicans shouted “socialism.” They failed to see the relevance of what Democrats were doing to improve their lives, and they likely didn’t hear from many local Democratic organizers about the importance of casting a ballot.

The electorate of the 2020s will be increasingly racially diverse and young. Studies show they’re not cowed by the word “socialism,” believe that systemic racism is a profound problem, and are eager to tackle the dominant structural challenges of the day. If Democrats run away from those realities for fear of name-calling by the right, they will fail to generate the necessary levels of support required to defeat opponents whose voters are participating in ever larger numbers.