A Night at the Movies With Brandon Mancilla

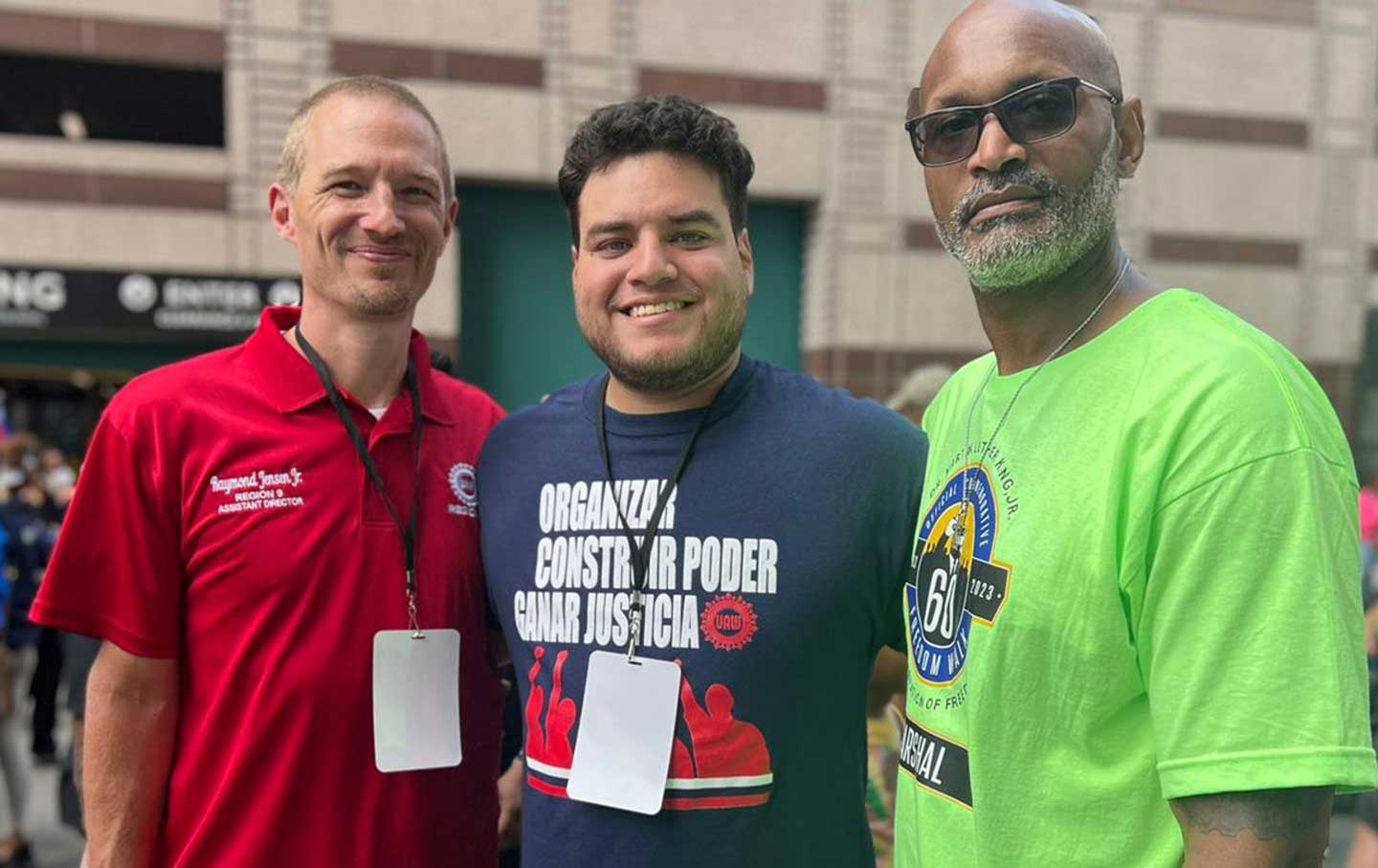

The new director of UAW Region 9A is part of a wave of young, politically active labor leaders organizing for a future where union power transcends borders.

As we sit down to watch Patricio Guzmán’s three-part documentary, The Battle of Chile: The Struggle of an Unarmed People, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Brandon Mancilla is checking his work phone. It’s the first week of the United Auto Workers’ strike against the Big Three automakers—Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis—the first time the union has taken on all three at once. He checks his texts as we wait for the film to start, his phone bringing dispatches from the history unfolding outside the half-empty theater. When I ask if work has been busy, his answer comes as half-sigh, half-laugh.

Mancilla is the newly elected director of UAW Region 9A, which covers eastern New York (including New York City), Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Vermont, Maine, and Puerto Rico. The region’s 50,000 current and retired members don’t include a lot of current Big Three auto workers, but there are a few shops: Ford has a parts depot in Connecticut, and Stellantis has one in Massachusetts. He started the day at the Stellantis plant, where he was checking in on strike preparations. The company has threatened to shut down the location in recent years, and he tells me the workers are eager to strike. (Since then, the company went through with shutting the plant down.)

In New York City, where Mancilla is based, much of the union’s recent growth has been in cultural institutions: Region 9A now represents workers at museums, book publishers, and movie theaters, including BAM. He’s a movie buff, and Guzmán’s masterpiece is his favorite film. He first saw it in college, and by graduate school he was teaching it to students himself. A regular at the city’s theaters, the soft-spoken labor leader demurs when I ask if he ever talks shop with the workers while buying popcorn.

The last time I’d seen Mancilla was at a bar in the Garment District in Manhattan. After a fundraiser for the Teamsters for a Democratic Union, a reform caucus, I’d led a contingent of the attendees to what Google Maps suggested was a sports bar. Upon arrival, I learned that I had in fact brought Mancilla and a bunch of Teamsters to a bar that encourages you to smash your glass against a wall in the back of the space upon finishing your drink. When that time came, I dawdled, convinced I’d be the first patron to die from a shard ricocheting back at me, and Mancilla gamely offered to join me. We donned safety glasses and hurled. I joked that should I ever be commissioned to profile a UAW leader, I’d take them here, the metaphorical possibilities too great to resist. Yet, when this assignment came, I was either too honest to reuse the setting, or just too lazy to go to Manhattan.

Instead, we’ve decided on something more tranquil. But before Mancilla can tell me much about his week, the lights go down.

Twenty-nine-year-old Mancilla hails from the union’s fast-growing higher-education wing, whose recent explosion in activity and membership is changing the face of the US labor movement: Today, roughly 100,000 of the union’s 383,000 active members work in higher ed. In 2017, he joined the Harvard Graduate Students Union, shortly before the graduate students voted to unionize. It wasn’t the first time: After a 2016 union election loss was overturned, the National Labor Relations Board found that the university had failed to provide an accurate list of eligible voters. Mancilla arrived on campus just before that second election. By 2020, he was its president.

Originally from Jamaica, Queens, Mancilla’s family comes from Guatemala, and both of his grandfathers were part of the revolutionary movements in that country and Nicaragua. By the time he’d reached Harvard’s history department, he’d inherited the family’s interests, studying the roots of the Guatemalan migration crisis.

He comes from a union family: His maternal grandfather was a union worker at a packaging facility in Long Island—he printed the labels that go on bottles and cans—and his father is a member of 32BJ SEIU, which represents more than 175,000 workers across a dozen states. His mom and his aunt were members of 1199 SEIU as home health aides. But for the young Mancilla, that mostly meant that they had better health insurance and retirement, a life noticeably more comfortable than that of the rest of the Guatemalan immigrant community. It was only when he started studying history, and the role organized labor played in revolutionary movements, that he began to wonder why US unions didn’t seem similarly political.

Last year, he joined a slate to run in the UAW’s leadership elections. It would be the first time those at the top of the union would get there because workers had voted for them directly rather than by gaming a delegate system that had allowed a clique to maintain control of the union for decades. The reform followed a corruption scandal that landed 12 UAW officials, including two former presidents, in prison. The union’s leaders had fleeced members for years, siphoning dues money to vacations in Palm Springs and the purchase of so many luxury goods that they had to use a semitruck to ship everything back to Detroit.

The challenger slate, UAW Members United, was backed by a reform caucus that had prevailed in a decisive 2021 referendum calling for the new direct leadership voting process. Mancilla is a member of UAWD, as is the UAW’s new president, Shawn Fain.

This year’s auto strike could never have unfolded the way it did without that leadership shake-up. In ways the previous leadership had not, the new guard put their faith in the rank and file rather than in amiable relations with the companies, which coalesced into an unusual and creative strike tactic: what the UAW termed a “stand-up strike.”

The name is an homage to the 1936 Flint sit-down strikes that built the union, during which workers refused to leave the plant until General Motors agreed to bargain. This year, rather than having all 150,000 UAW members at the Big Three walk off the job simultaneously, the union called out specific shops in waves. This way, the strike grew over time, spreading from parts manufacturers to hugely profitable assembly plants, ramping up pressure on the companies when they failed to deliver meaningful progress at the bargaining table and keeping them guessing as to which plants the workers would take out next. The tactics and strategy demonstrated military-like discipline—like guerilla warfare.

For Mancilla, the experience is like a dream fulfilled, if an unusually exhausting one. The prior leadership let problems fester: Structures fell into disrepair, and many members lost hope. There’s a lot to fix. “It’s nonstop,” he admits. “We’re doing something incredibly historic and once in a generation. So it’s remarkable, but you also pinch yourself. You don’t know how you’re doing it all.”

Part one of The Battle of Chile opens in 1973, two years into President Salvador Allende’s attempt to transform Chile into a social-democratic country as it faced down a political economic crisis. He had the allegiance of much of the country’s working class, who saw him as the workers’ president. This bloc was organizing to push his policies forward in the face of right-wing meddling and sabotage. But a small segment of workers opposed him, and with the backing of the Chilean right and the United States, they sowed chaos.

A work stoppage by copper miners at El Teniente, at the time the largest underground copper mine in the world, hobbled the Chilean economy. A strike by truck drivers, who stayed afloat courtesy of millions of dollars from the CIA, further turned the screws. The AFL-CIO, too, channeled millions to Allende’s foes through the American Institute for Free Labor Development, one of the US government’s Cold War–era labor institutes. (Thus was born the moniker “AFL-CIA.”)

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →By the fall of 1973, a coup was unfolding. At the end of part two, The Coup d’État, the Presidential Palace is being bombed, and Allende addresses the public one last time before his death: “The only thing left for me is to say to workers: I’m not going to resign! Placed in a historic transition, I will pay for the loyalty of the people with my life. And I say to them that I am certain that the seeds which we have planted in the good conscience of thousands and thousands of Chileans will not be shriveled forever.”

No US union leader can deny this history, in which the labor movement in the United States undermined the liberation of its counterparts abroad. The lights go up and, in stunned silence, we relocate from BAM to the Mexican restaurant across the street. Allende’s words ringing in my ears, I mumble through a discussion of drink orders and then attempt to put to words what is preoccupying me. I ask about the contradiction of being a socialist labor leader in the imperial core. Mancilla smiles and nods and then, by way of an answer, brings up electric vehicles.

EV plants, even those operated by the Big Three, aren’t covered by the UAW’s contracts. The union has made addressing this problem a priority, criticizing Biden for failing to find a way to attach workplace standards to EV manufacturing and searching for a path to organize those workers. It’s an existential issue: Should the UAW fail to find a solution, the growing sector will create a parallel low-wage, unsafe labor market, undermining union standards and further decreasing the union’s density in auto manufacturing.

While Mancilla agrees that it is important to focus on the EV sector, he feels that members’ vision should not stop at the country’s borders. Otherwise, US workers will once again fail their brothers and sisters around the world. Plus, “an injury to one is an injury to all” isn’t a mere slogan but a description of what letting employers harm some workers does to the rest. For the UAW, failing to build solidarity with auto workers abroad would only hurt itself.

“In all the talk about the Green New Deal and the UAW’s demands of Biden, I think we also need to have, at the very least, a North American vision for what that looks like,” says Mancilla. Otherwise, the EV sector will develop much like legacy auto, with employers outsourcing work south of the border as a means of disciplining workers in the United States. Mexican workers, too, are a parallel low-wage labor market.

“But the Mexican independent union movement is a left-wing movement, which means building alliances with them is a political choice,” says Mancilla. The union’s members will have to share strategy and resources, and take seriously the needs of the Mexican working class, many of whose members lack good-quality drinking water and whose children face poverty and malnutrition. “To elevate the standards for all of us, we’re going to have to work together,” he says. “We want justice across the supply chain.”

“Why don’t American unions pose political questions?” asks Mancilla, reflecting on the film. It’s a question he’s pondered ever since he realized that his understanding of his own family members’ union membership had been limited to the bread-and-butter. “It’s a massive question Allende posed,” he continues. “The more the left of labor grows, the more political our questions and choices get.”

Over the last 40 years, the US labor movement has focused on training fellow workers on the basics of good unionism: how to file a grievance, how to run a contract campaign, how to pull off a strike. There is plenty of valuable strategizing and debate about political reform: Some unions support universal healthcare and candidates who do likewise, while others don’t. Some emphasize sectoral bargaining. All agree that US labor law is entirely inadequate. But truly ambitious, liberating political visions have rarely gained traction.

The new UAW may be changing that. The summer auto strike provoked frantic political scrambling. Joe Biden, not yet endorsed by the union and fearful of losing a key voting bloc, became the first US president to ever walk a picket line. Donald Trump traveled to Michigan the next day to pretend to speak to the striking autoworkers. “Our union has been on the decline for decades,” Mancilla said. “So for a little bit of fight to garner this much interest from the political class just shows how much more we can have.”

Some of this political fight comes from new leadership. As president, Fain leads with a mixture of militancy and religiosity that Mancilla said reminds him of the socially progressive Christianity around which he grew up. “I am secure in every decision we have made because I have faith in our members,” Fain said during his strike announcement, after quoting from scripture. “So I have to ask you: Do you have faith? Are you ready to stand up together and move that mountain? Because nobody is coming to save us. Nobody can win this fight for us. Our greatest hope—our only hope—is each other.”

While the Big Three executives hoped that Fain was on his own and dismissed his proposals as fringe, the strike proved the opposite. Not only had Fain won the mandate of the membership; he and his fellow newly elected leaders had won the backing of many of the members who had voted against them—and they did it by proving that they trust the rank and file. “The more Shawn stood by the demands and the more we stood by them, the more the members said, ‘Oh, yeah, they really are our demands,’” Mancilla said.“The companies had no idea what to do.”

In July, the Teamsters showed how powerful, and frightening, mass unity could be. The union prepared to strike the United Parcel Services, where some 340,000 of their members work. It’s the largest private-sector contract in the United States, and an estimated 6 percent of the country’s gross domestic product moves through the company’s trucks. As the union held practice pickets outside UPS hubs across the country, the specter of a work stoppage of such magnitude led to growing demands from the employer class that Biden step in. That the president chose not to do so, abiding by the union’s request that he stay out of the dispute, was itself a win for labor. When workers at such a scale exercise their leverage to wrest gains from their foes, is this a form of political action? “If you can shut down the entire supply of goods for the entire country,” says Mancilla, “you will encounter these questions.”

I bring up a scene in the film: A worker addresses a member of a trade union council, his exasperation palpable after listening to the speaker argue for what amounts to technocratic calm in the face of growing right-wing sabotage and violence. The worker speaks at length, but his question boils down to: Do you trust the workers or do you not? This, ultimately, is what Mancilla sees as the core political question.

“It’s not about political endorsements,” says Mancilla. “It’s about: What demands are you putting on the table? What political education are you engaging in? And what fights are you willing to have amongst the membership instead of hiding from the fact that you have conservative elements and real disagreements in the union movement?”

“We’re not there yet,” he said. “But we’re going to get there.”

On December 1, a contingent of labor organizations gathered just outside the gates of the White House. They were there to to draw attention to a hunger strike, then on its fifth and final day, organized to build pressure on the Biden administration to call for a permanent cease-fire in Gaza. New York State Representative Zohran Mamdani introduced the first speaker: Mancilla.

He opened with a quote from Walter Reuther, the renowned former UAW president: “In 1968, when Walter Reuther stated his opposition to the Vietnam War, he said, ‘We must mobilize for peace rather than for wider theaters of war in order to turn our resources and the hearts, hands, and minds of our people to the fulfillment of America’s unfinished agenda at home.’”

“What he meant by that,” he explained, “was that the labor movement would not be able to achieve the transformative goals it has for social justice, for worker justice, for economic justice, if it turned a blind eye to what was happening across the world.” With that, Mancilla announced that the UAW international had voted to join the call for a permanent cease-fire and investigate the union’s economic ties to the conflict, such as shops that manufacture weapons used by Israel.

“That is as important as anything else we’re doing in this country to ensure that workers and poor people and oppressed people across the world are on the path to winning the justice they so deserve,” Mancilla said. “For so long we’ve been silent, and we’ve been ignorant in the labor movement on this issue. That time is over.”

More from The Nation

Enough With the Bad Election Takes! Enough With the Bad Election Takes!

To properly diagnose what went wrong, we need to look at the actual number of votes cast.

No, Kamala Harris Staffers Did Not Run a “Flawless” Campaign No, Kamala Harris Staffers Did Not Run a “Flawless” Campaign

Democratic strategists are still patting themselves on the back for a catastrophic defeat.

The Courts, Trump, and Us: A Q&A With David Cole The Courts, Trump, and Us: A Q&A With David Cole

Last time, the courts were an essential checking force on the Trump administration. This time around, they may again provide a check—if we push.

Congresswoman Barbara Lee on Why Shirley Chisholm Was Right Congresswoman Barbara Lee on Why Shirley Chisholm Was Right

The California Democrat explains why, during her 25 years in Congress, it was important for her “to disrupt and dismantle and build something that’s equitable and just and right.”...