Harvard’s Next President Must Champion Climate Justice

With Claudine Gay’s resignation, the university has an opportunity to truly grapple with their role in the climate crisis.

On January 2, after making history only six months earlier by becoming Harvard’s first Black President, Claudine Gay resigned in one of the more painful chapters in the school’s modern times. The university now faces the challenge of selecting its next president, and with that challenge comes a crucial opportunity: Harvard’s leadership has a chance to grapple seriously with the university’s role in the climate emergency.

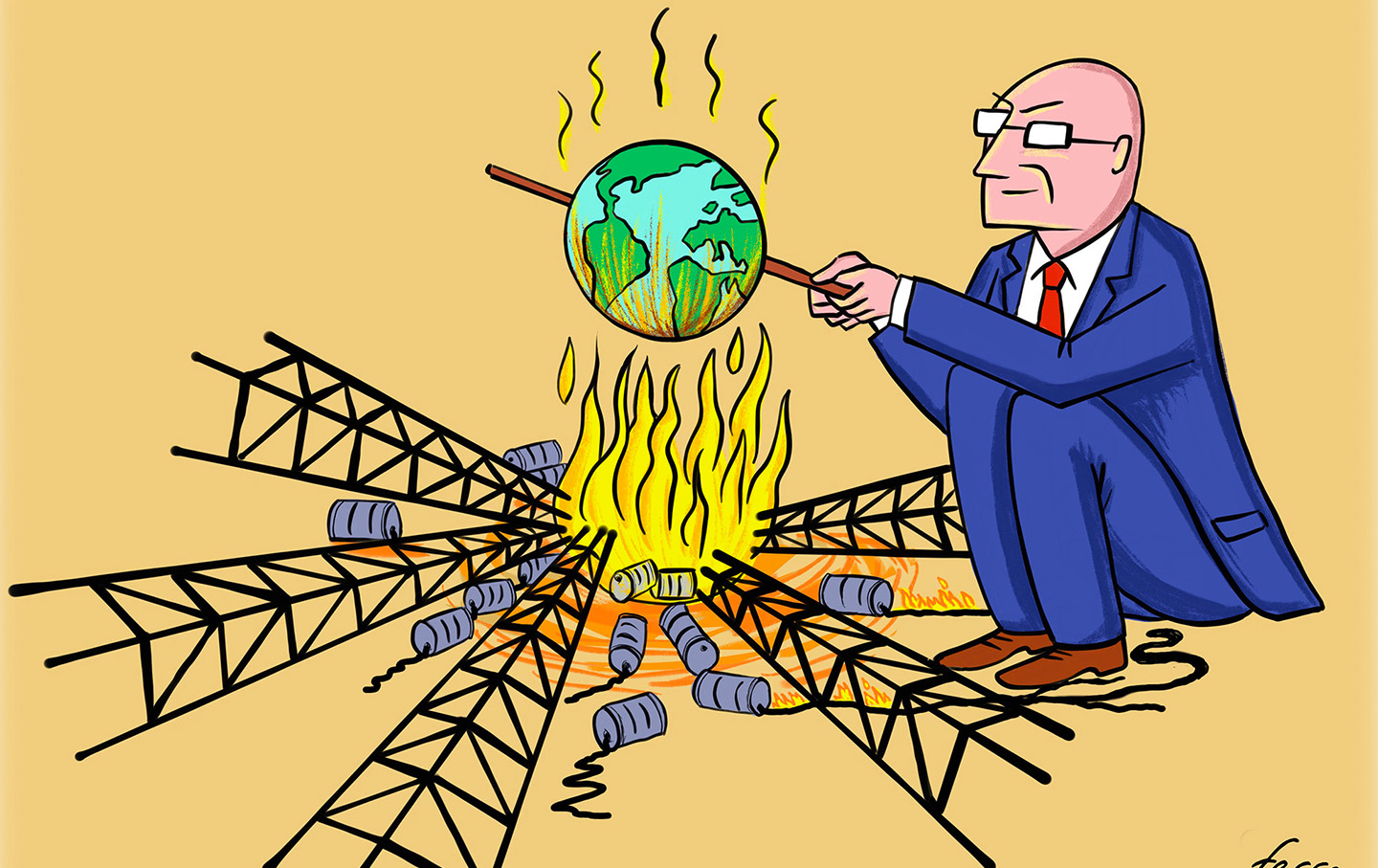

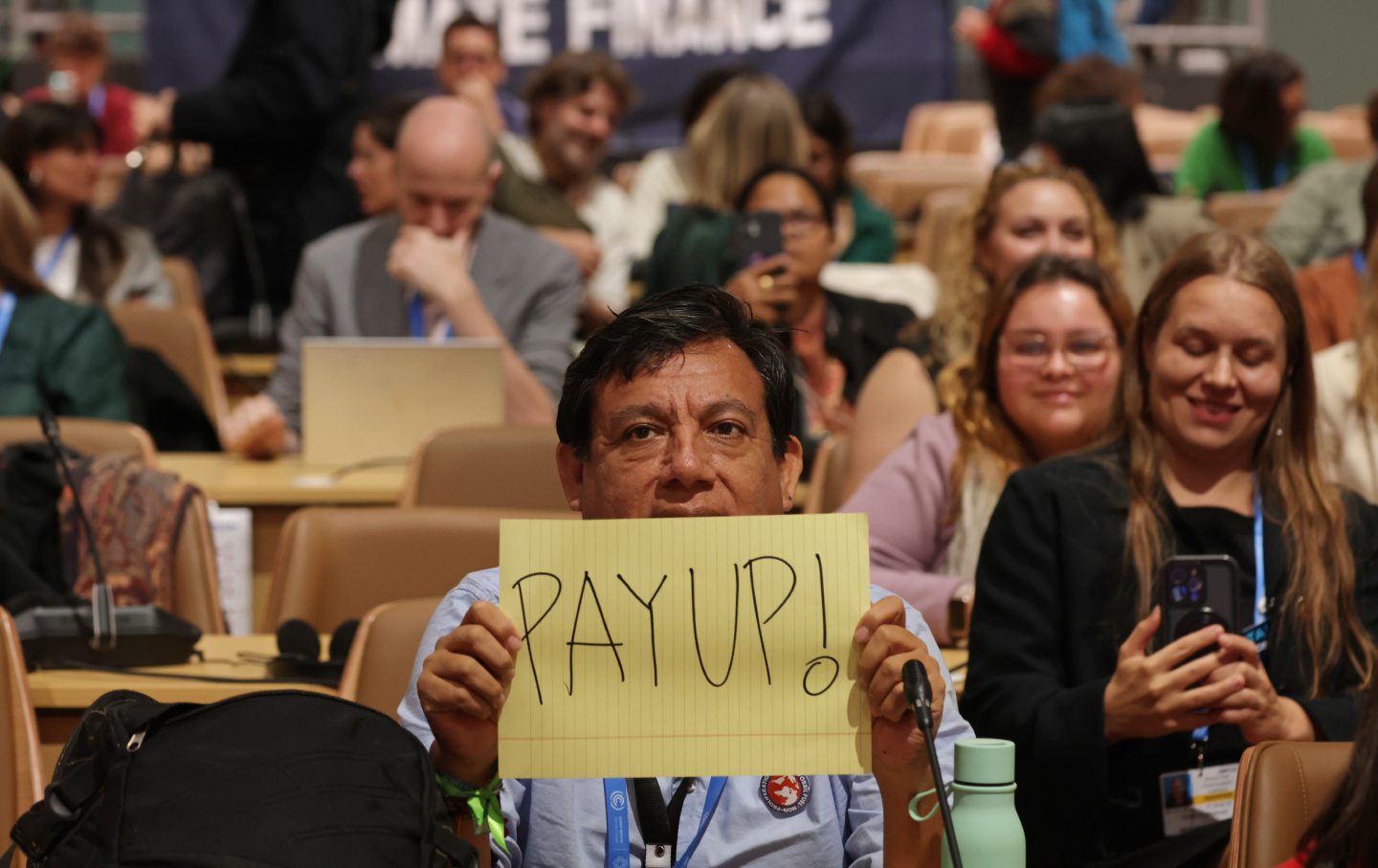

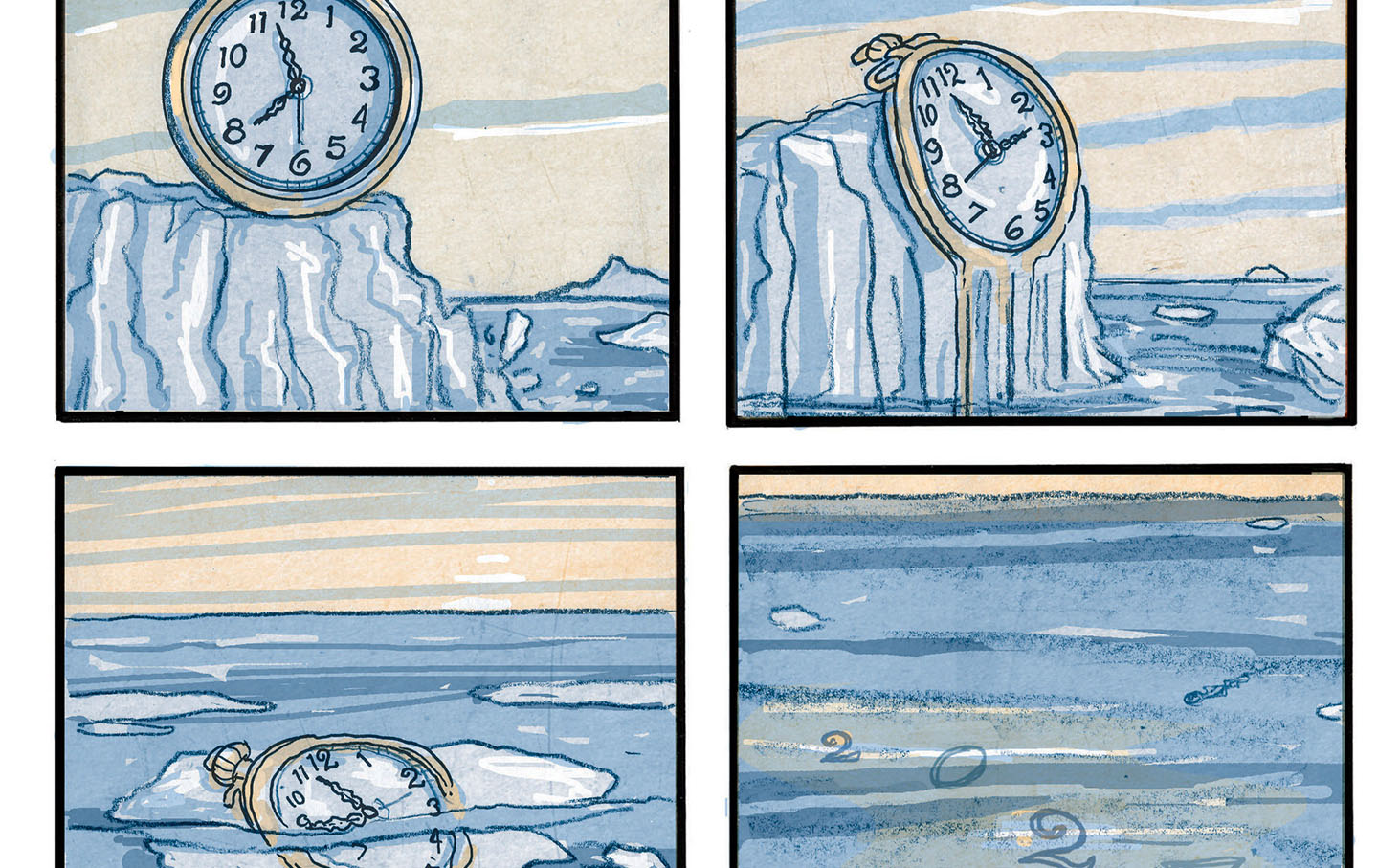

In 2023, the world saw the ninth consecutive hottest year on record, experienced a terrifying sample of life with 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming—the limit targeted by the Paris Agreement—and failed to agree around phasing out fossil fuels at COP28, where fossil fuel lobbyists predominated over national delegations.

At a moment of existential urgency, with a few years left before we inhabit a dangerously warmer world, there is no equivocation: The next Harvard president must be the climate justice president.

In 2021, thanks to the divestment and climate justice movement, Harvard committed to divesting its over $50 billion endowment from the fossil fuel industry, recognizing that investments in the industry contradicted its core mission and fiduciary duty. Albeit late, given that numerous peer institutions had already pledged divestment, the policy change was still a historic tipping point, inspiring a host of major investors from more universities to pension funds and philanthropic foundations to follow suit.

Crucially, it signaled a new willingness by Harvard to question the financial, moral, and social support it affords to companies undermining students’ futures, harming marginalized communities, and wrecking the planet.

Yet, outside its endowment holdings, Harvard remains deeply entangled with the fossil fuel industry, undermining the express goal of divestment and the understanding that fossil fuel companies’ business model and insidious anti-climate behavior are antithetical to the university’s mission.

Most notably, Harvard still accepts research and programmatic funding from fossil fuel companies like Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Shell, and the university received at least $20 million from four major fossil fuel companies between 2010 and 2020.

Since these companies have a long history of deliberately misleading the public about climate change, partnering with them in research—specifically, research that informs our understanding of climate solutions and influences climate policy—poses a grave conflict of interest and is not only a bad-faith act but also a deeply hypocritical one for an institution claiming to care about climate action. The public understands these issues: When a Data For Progress study made voters aware that Harvard took fossil fuel money for climate research, their favorability toward Harvard dropped 14 points.

But research sponsorship is only one way that Harvard stays cozy with Big Oil. The university also allows fossil fuel companies to recruit its students on Harvard’s career search site and hold in-person recruitment events around campus. Harvard also considers Liberty Mutual, a major fossil fuel insurer, to be among its “premier employment partners,” and Harvard Law School produces the second-largest total number of fossil fuel lawyers out of the country’s top 20 law schools.

Given these entanglements, a climate justice president needs to go beyond reaffirming Harvard’s hole-filled net-zero endowment pledge and plans for sustainable technology on campus or climate talk in the classroom. They need to acknowledge the enormous influence that Harvard has on higher education and globally and direct that influence to advance not just new technology and research but true climate justice. Such justice begins with full dissociation from the fossil fuel industry in research, recruiting, and all other areas—a complete end to Harvard’s enabling and legitimizing this industry’s agenda of profiting off continued climate breakdown.

With Harvard confronting hard questions about its leadership, the school must also move to democratize its closed governance and ensure representation for climate justice perspectives, and further address the conflicts of interest posed by its current leadership having personal fossil fuel ties—long overdue steps. More immediately, Harvard’s Interim President Alan Garber has a clear responsibility to lay a new foundation: kick-starting Harvard’s separation from Big Oil and ensuring that climate justice is a central focus in evaluating candidates’ qualifications for the job. The next steps should include a just reinvestment of Harvard’s endowment into local Cambridge communities and the greater Boston area to support climate resilience.

With 2024 predicted to feature further record-breaking heat and unnatural extremes, the climate crisis and climate injustice are on our doorstep. We can’t afford to wait another decade for Harvard to make the right call, which is why we’re continuing to organize in force and seeing new progress every day.

As an alumnus and undergraduate of Harvard College, experienced climate activists, and young people whose futures are at stake, we firmly believe that this is the moment for Harvard to embrace the mantle of climate leadership it has long shirked. Harvard must separate from the fossil fuel industry now and set a powerful, urgently needed example. Our movement and the world are watching.