What Good Is Architecture on a Drowning Planet?

We need political solutions to climate emergencies, not design solutions.

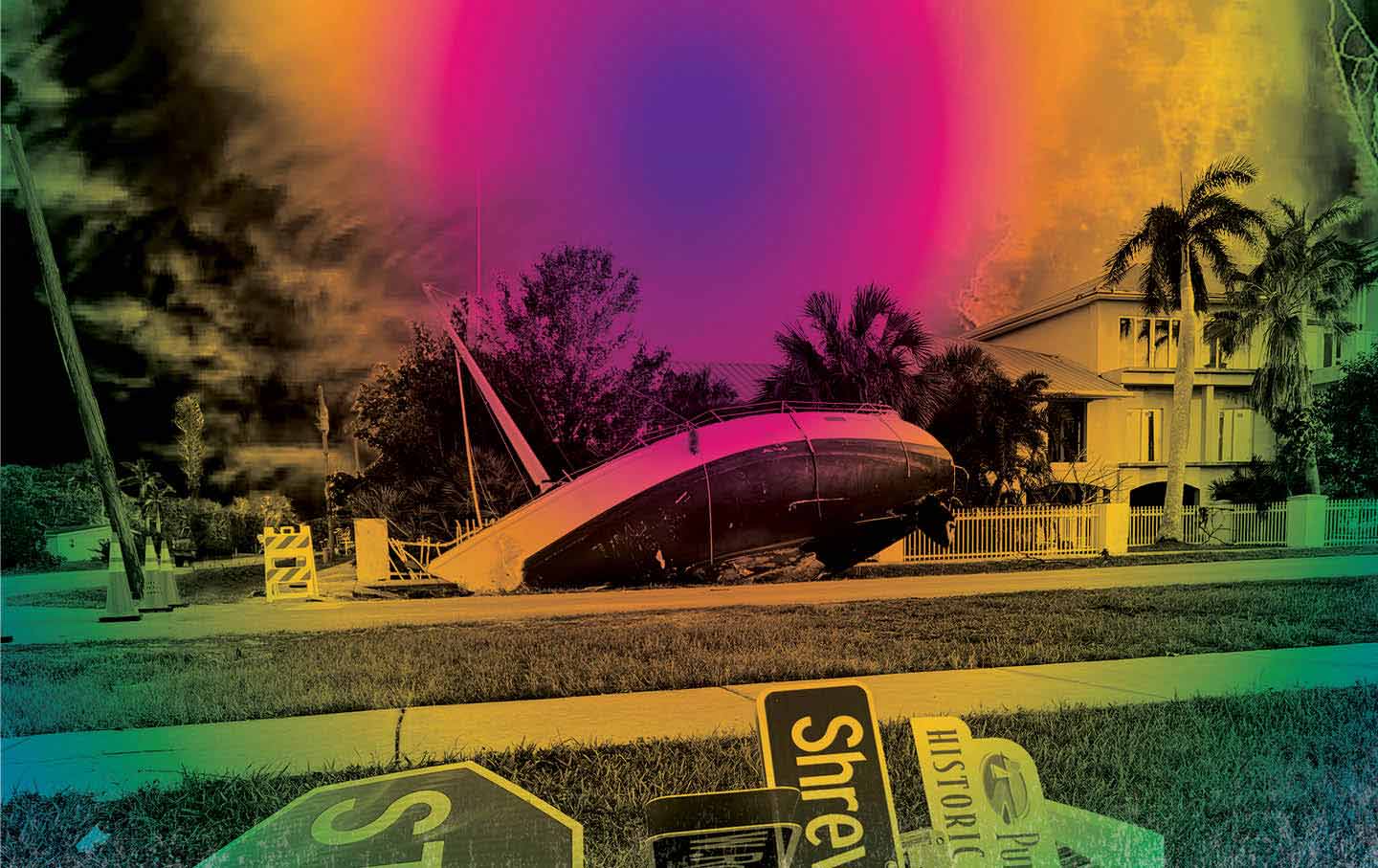

Never does the future look so bleak (or the road the ruling class will choose so clear) as it does during an emergency climate event. New York City Mayor Eric Adams’s sluggish, nearly indifferent response to the catastrophic floods that hit the city in late September just about said it all: He asked snidely whether he should bear responsibility if a “meteor fell to the planet Earth.” He did not mention the thousands of people who live in illegal basement apartments in Brooklyn, apartments that exist because safer housing is beyond their inhabitants’ financial reach. Nor did he mention that the infrastructure the city has to mitigate emergencies such as these is clearly inadequate. As images circulated on social media of flooded subways and even buses, people trudging through waist-high water with trash bags as makeshift wading pants, and underground fires blazing because of electrical short-circuits, it became evident for the umpteenth time that this is simply the way it will be. Those in power will let the vulnerable languish at the expense of the wealthy. They will sign off on billions of dollars in policing to ensure this status quo, even as income inequality becomes steadily more dire and public infrastructure is pushed to its absolute limit.

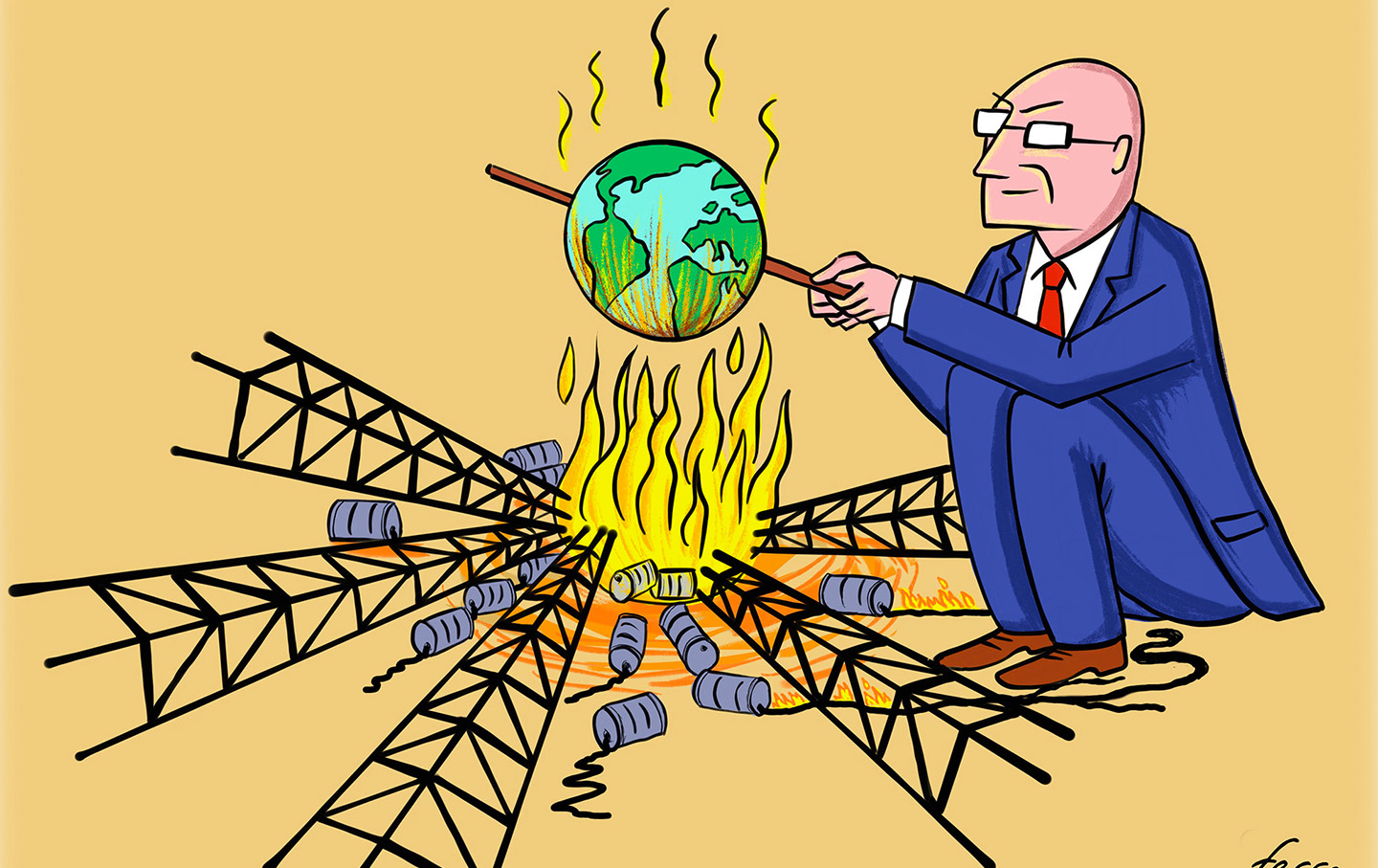

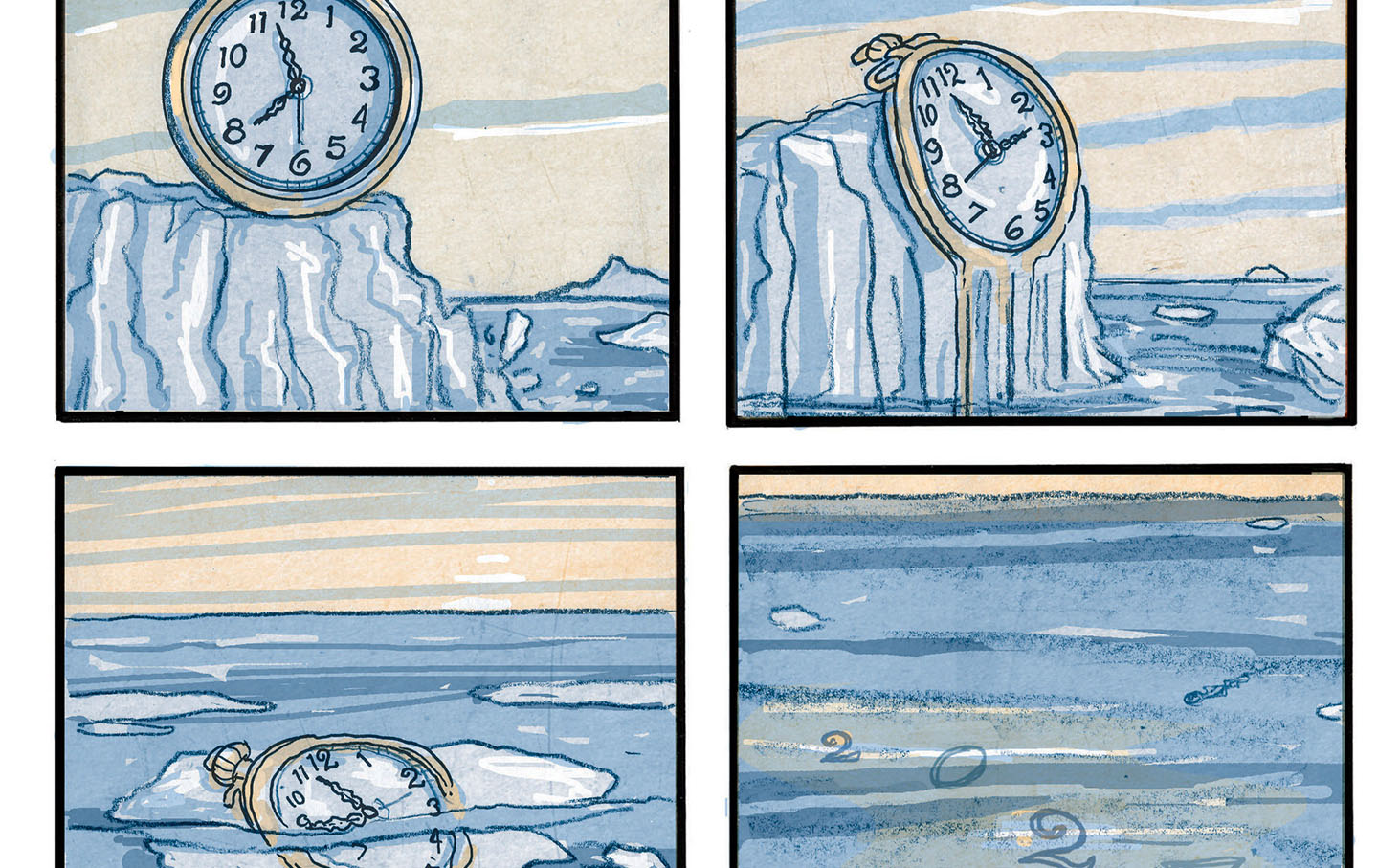

Climate change is an interesting beast from the perspective of architecture and urbanism, fields prone to self-aggrandizement and technocratic solutionism. It feels very solvable in a design sense. We know all the right answers: reduce cars and surface pavement, invest in landscape strategies for flood abatement, reinvest in public infrastructure and future-proof it, build more densely and with more carbon-friendly techniques, eliminate sprawl. These are very important and practical solutions—yet, they’re not being employed at scale, are they? This is a political breakdown, not a design flaw. Yet I don’t want to suggest that architecture is powerless and can only be complicit in the ills of the world, a mere servant to unconquerable capitalism. If design cannot solve climate change, what is the point of it in a warming, flooding world on fire?

Architecture is a way of organizing capital, one of many. Contemporary architecture, quite literally, corrals different commodities in the form of a building, through processes that have been streamlined by modern software, fabrication technologies, and ever-more stratified divisions of labor within firms.

If we think of architecture this way, then it should not surprise us that the discipline serves those in the highest positions of power. The essence of New York architecture is not climate-resilient buildings or retrofits but rather the supertall skyscrapers, from which the ruling class can look down with pity at the flood in air-conditioned comfort. It makes sense that the field’s most media-savvy leaders are not pushing such unsexy interventions as surface-water management, strategic allocations of green space to reduce flooding, or even simple (desperately needed) maintenance like urban drain cleaning. Instead, our starchitects are producing renderings of think tank–funded floating cities, touted as classless utopias, but implicitly reliant on an invisible underclass of logistics workers—see Bjarke Ingels’s Oceanix City concept. The idea of starting over rather than saving what we have is very appealing to architecture’s world-building instincts, its desire to organize the world as efficiently and correctly as possible. It makes for nice publicity. It doesn’t require changing anything, just dreaming into the void. It is this kind of solutionism that must be resisted at all costs. An architecture not rooted in the world we live in and the crises we all face is useless.

And yet, if we think of architecture as a form of organizing capital, we should remember that the field has a long political history of dissent and resistance. The stratified division of labor and ruthless technocracy of the architecture firm is not so different from that of the factory. The history of the built environment has not usually been one of peaceable benevolence, but one of profound and meaningful struggle. I find this invigorating: It lets us strip architecture of its paternalistic, world-building pretensions and reveal it for what it really is, something material and made possible through labor. This is much more useful than holding on to the illusion that if we simply design really well and get enough grant money, the powers that be will look favorably on us and let us build our way out of disaster—never really asking who will be saved by our interventions and who will perish for lack of them. Architecture is neither omnipotent nor powerless. It is a tool. Right now, neither architecture firms nor those who employ them have a democratic way to determine how to use that tool.

What that democratic decision-making looks like in practice is difficult to foresee, for we live in deeply undemocratic times. It could look like labor organization that gives architectural workers the power of rejection—to say, “This project is bullshit.” It could look like architecture engaging with movements beyond it—the movement for a Green New Deal, for example—in a more substantive way than just attending conferences or publishing white papers that smooth over political demands. I myself don’t know the answer, for the question of democracy is never for one person alone to answer. What I can say is that in the time I’ve been working in the field, I’ve seen worsening disillusionment: Young people are put through grueling schooling with the belief that they will have agency to shape the built environment in meaningful ways, only to find out that their job looks more like data entry than art. They find themselves answering to faceless corporate employers or famous architects who grandstand on 60 Minutes about how they’re changing the world—while their workers toil for 11 hours a day finishing construction documents for a museum sponsored by petro-state blood money.

The facade of architecture as a force for good is crumbling, and I would posit that the work of the most famous architects is more alienated from the public than ever before. Even the modernists gave the proletariat public housing at the same time it gave them Taylorism. The postmodernists gave us the mall and Disney World and, through their false populism, at least claimed to stand hand-in-hand with the everyman. What does Ingels or Rem Koolhaas or Zaha Hadid’s firm give us? Half-baked theory? Houses for rich people? A soccer stadium built with slave labor?

We’re at a breaking point. To move forward, we must understand that architecture’s climate solutions, even though they are hyper-technical and backed up by good planning or good science, are still political. What use is something like Passivhaus if it only remains an option for the environmentally concerned single-family homeowner? What use are even the most paltry environmental protocols like LEED certifications for energy efficiency if they are used to build greenwashing headquarters for ExxonMobile? If these questions were not already at the forefront of the field, then events like the flooding in New York, the fires in California, or the hurricanes in Florida are showing us that the status quo—not only in architecture but in the very world we live in—is becoming untenable. The time to answer “Which side are you on?” is now.