One of photography’s secret powers is to turn time inside out. It takes a constellation of happenings that occupied a fraction of a second and makes it available to attention over a long span of time. And yet the picture always collapses back into instantaneity. This is something that William Klein has thought about. “A picture is taken at 125th of a second,” he once observed. That means that when you see 125 images by any photographer, you’re seeing one second of their life. “The life of a photographer, even a great photographer as they say: two seconds.” That’s about what’s encompassed by the photographs alone in the current exhibition at New York’s International Center of Photography, “William Klein: YES: Photographs, Paintings, Films, 1948–2013.” But even with some 300 works on view—two and a half seconds of life!—the ICP exhibition, curated by David Campany and on view through September 12, left me hungry for more; every one of those tiny morsels of time encapsulated in his imagery is so teeming with energy, with life. The brash optimism of the three-letter upper-case affirmation in the show’s title reflects the enthusiasm that permeates all of Klein’s endeavors: His willingness to try anything, his will to experience everything, his determination not to miss out on witnessing and participating and fighting, are just what we need in these most discouraging of times.

Klein is by election a Parisian but by birth and character a New Yorker. Born in 1928, his Jewish immigrant family lived uptown—110th Street and Fifth Avenue, the edge of Harlem—but his father’s clothing store was on Delancey Street on the Lower East Side. He was a whiz kid who finished high school at 14, then left City College for the Army as soon as he was old enough, serving in the occupying forces in Germany in 1946. The GI Bill paid for his further education—under Fernand Léger, the French painter who, earlier in the century, had bent the rarefactions of Cubism in the unexpected direction of a sort of populist propaganda for modern society as a collective machine under construction. We’ve been so convinced by the story that modern art shifted its center of gravity from Paris to New York in the 1940s that it’s always salutary to be reminded that the City of Light maintained its magnetic attraction for young American artists in the postwar decades. Léger’s school seems to have had a particular appeal; aside from Klein, Léger’s pupils included San Francis, Paul Georges, Shirley Jaffe, Jules Olitski, Beverly Pepper, and Richard Stankiewicz—not to mention Robert Colescott, whose own retrospective, “Art and Race Matters,” currently at the New Museum of Contemporary Art through October 9, should not be missed. That’s a particularly varied group, none of whom ended up doing work that overtly signals Léger’s influence. In Klein’s case, it was his teacher’s insistence on the urban scene as both primary subject and setting that would have a lasting impact. “Work in the city, and get out of the galleries” was Léger’s mantra. “At that time,” Klein later recalled, “there were big painted tableaux outside of movie houses, where a guy would take one photograph of a scene from the movie [and] make a big mural to advertise it. And Léger said, these guys are working in the city and what they’re doing is much more important and relevant than what you’re doing jerking off in the studio here.”

A few of Klein’s paintings are at the ICP—brightly colored, geometricized depictions of the contemporary world that owe as much to Stuart Davis as to Léger. He seems not to have quite figured out how to integrate his figures with their setting, and one piece drops the figure altogether in favor of pure abstraction; what it gains in coherence it loses in punch. But abstraction turned out to be the catalyst for Klein’s beginnings as a photographer: While his wife was helping him document a painted room divider he’d made with movable and rotatable panels, she started spinning the panels—and he became intrigued by the blur that resulted when he shot the picture. “Hard-edged painting could turn into soft-edged photography,” as Campany aptly says in his essay for the show’s forthcoming catalog. Through photography, Klein discovered a dynamism that his paintings could not match.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Klein had some success with the abstract photographs he began producing—they make covers that are almost too hip for LPs with corny names like Ping Pong Percussion and Clarinet Marmelade, but they remain fundamentally ornamental. Still, they caught the attention of Alexander Liberman, the renowned art director of Vogue, who in 1954 brought Klein back to New York and put him to work as a still life photographer. But the ex–Léger student’s heart was still in the street. His adventures roaming the city became a legendary book, Life Is Good and Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels, published in 1956. For all its almost cynical irony, the book’s title also suggests an affinity with the “spontaneous bop prosody” of Klein’s Beat contemporaries; one feels that he was using his camera the way they would their typewriters, shooting “excitedly, swiftly,” as Jack Kerouac recommended for writing, “‘without consciousness’ in semi-trance…allowing subconscious to admit in own uninhibited interesting necessary and so ‘modern’ language what conscious art would censor.”

Having spent eight years abroad, Klein saw his hometown as a place of astounding momentum and implicit violence. In Harlem, men striding down the street look more like they’re dancing than walking; half a dozen piled-up copies of the Daily News form the rat-a-tat visual poem gun gun gu gu gu gunma[n]. Treating documentary street photography with the same freedom from preconceptions with which he’d approached abstraction, Klein plunged into the swirling currents of the city and was willing to sacrifice clarity for intensity in his images, using off-balance composition and high-contrast black-and-white to probe the chaotic surfaces of urban life.

What the photographer Martin Parr said of Klein’s book—that it functions as “an accumulation which creates this noise, which gives off energy which reflects so accurately what was going on in New York in the 1950s”—is even more true at the ICP: Images from the book (and others from the same period) explode on to the wall, all the more powerful for being enlarged and crammed together nearly without any more space between them than their thin black frames afford, so that their centripetal energies seem to stoke each other. Far more than in a book, and in a way that could never have been imagined with the exhibition conventions of the 1950s, Klein’s pictures create an environment that’s greater than the sum of its parts and that echoes what he must have seen and felt as he roamed New York’s streets. He would return to those streets again—more specifically, to Brooklyn—in 2013, producing a series of color images that, while warmly affectionate in their view of the borough and its people, lack the graphic oomph of his black-and-white work in the 1950s.

Klein didn’t stay long in New York. Vogue needed someone in Paris, and, perhaps against his own inclinations, fashion photography became his bread and butter. Again, he handled the genre with unprecedented freedom—a sense of possibility that was undoubtedly fueled by his own disrespect for the job. “There was always a sarcasm in my fashion pictures,” he said. As art historian Martin Harrison observed in his history of postwar fashion photography, “some of the dissonance of New York spilled over into [Klein’s] fashion photographs, changing the rules, and opening it up in an extremely influential way.” Klein turned the studio into a kind of laboratory where he could experiment with just about any technique that allowed him to introduce an element of the unforeseen into the previously uptight, comme il faut realm of fashion imagery, even using some of his old tricks to create abstract passages, yet always taking care to let the clothes retain the visibility that his employers demanded. His success in the field, you could say, came from how he almost inadvertently pays the clothes the high compliment of assuming that they sell themselves, allowing him to concern himself with other things. “I had no training or wish to respect traditional techniques,” Klein said. “My photographs were primitive—anything goes, anti-techniques: this suited me.”

Likewise, he used the street as a studio in which the disconnect between the precious artifice of couture fashion—and of the fashion model with her exquisite pose—and the demotic hubbub around it suggests an overlay of different, perhaps opposing perspectives. The effect can be ironic or charmingly befuddling. Klein seems to lampoon the very enterprise of fashion, but in an affectionate way. In one brilliant image, published in Vogue in 1959, a trio of women in immaculate white dresses and gloves and sporting fanciful headgear strike their attitudes on a gritty Manhattan rooftop. One of the skyscrapers behind them is under construction; the city is on the move. Two of the models hold nearly full-length mirrors that seem to multiply the three into six and remind us that the mirror always reflects something a bit different from what the eye shows us directly: The expression on each face—always cool if not cold—appears different depending on the mirror’s angle. An arithmetic progression seems to govern the picture: One woman is not reflected in either mirror, so we see her only once; another is reflected in just one of the mirrors, so we see her twice; and the third is caught by both mirrors, so she appears three times. In this proliferation of figures, there is something as sinister as it is seductive.

Having explored his hometown with his camera, Klein soon turned to his adopted city of Paris as a subject, as well as to Rome, Moscow, Tokyo—wherever opportunity and intuition took him over the next few years. Each of these journeys led to a book, and again, each series becomes a joyously crowded wall at the ICP. In each place, he found something different. In Paris, we sense a similar double consciousness at play as in his New York pictures, but the rhythm of the city is less frenetic—amenable to a more deliberate contemplation. On the other hand, Rome seems to have offered more resistance to Klein’s gaze. The reason, perhaps paradoxically, lies in the city and its denizens’ theatrical flare in everyday interactions—their consciousness of figura (one’s appearance, the impression one makes) somehow keeps the photographer at a distance; whereas his fashion images could play with the contrast of the posed and unposed, this more subtle interplay between the two often seems to baffle him. On the other hand, crossing the Iron Curtain—still a rare thing in 1959—Klein appears to elicit an implicit sympathy, and his gaze singles out individuals (for instance, a bikini-clad young woman in a park who seems overjoyed at being photographed, even as a white-suited old man sitting in the background observes with a look of grumpy mistrust) more than the crowds that drew his attention elsewhere.

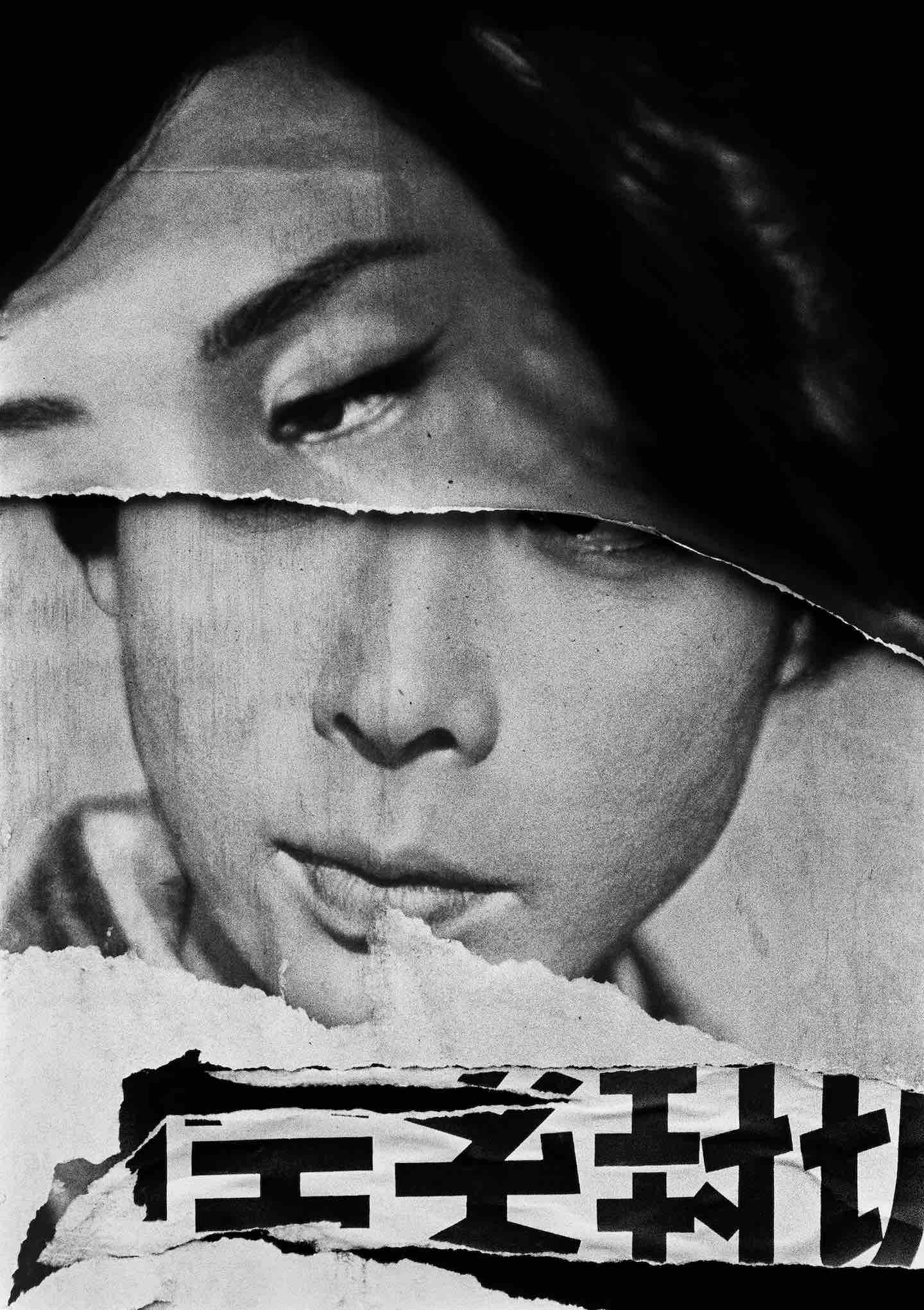

But the most fascinating of Klein’s city cycles, after that first series from New York, is the one he made in Tokyo in 1961. According to him, it was his biggest challenge, given the linguistic and cultural barriers involved, “the first time I was photographing unknown scenes and objects” and trying to make sense of them, “depending on my feelings and obliged to make photographs of the nonidentified, of another world. I guess this was the test of photography.” He passes the test with flying colors—or perhaps I should say, with flying black-and-white. As is his wont, he makes his way through the city by heedlessly throwing himself into its rhythms. His goal is not to clarify, not even to understand what he sees, but simply to register what’s there. Again, mirrors sometimes play a part: In his photographs of a woman’s hair salon, they multiply the handful of beauticians and customers into a seething crowd. The salon becomes a self-contained hallucinatory world of its own. Curiously, the intensity of Klein’s outsider view of Tokyo helped spark the remarkable school of Japanese photographers who were about to emerge in the 1960s—for instance, the great Daidō Moriyama, who (as Campany informs us) has said he “tirelessly browsed through the pages of Klein’s photographs, which ultimately helped me determine the direction of my own endeavours.”

Having become a hero to his fellow photographers around the globe, Klein was ready to try something else. He continued his fashion work to pay the bills and later made many television commercials as well, but his own deeper inclinations led to cinema. And the times led him to a passionate plunge into the political upheavals of the 1960s—anticolonial uprisings, the movement against the war in Vietnam, the struggle for Black liberation in the United States and around the world—all of which became his subjects. He’d already made a remarkable short film in New York in 1958, Broadway by Light—a lyrical meditation on neon, a medium, like photography, for transmuting advertising into beauty. But from the early 1960s through the mid-1980s, he was above all a filmmaker. His oeuvre in moving images includes three wildly imaginative fiction features, close in spirit to Pop art, among them Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? (1966), an affectionate send-up of the fashion world itself. But his genius was for documentaries, of which he made many. In the ICP’s galleries, the 10-minute Broadway by Light is shown in full, while a few others are aptly presented by way of brief excerpts, along with stills, storyboards, and the like. My recommendation is to go online and seek out as many of Klein’s documentaries as you can find.

The improvisational flair evident in Klein’s fleet, dynamic style of documentary filmmaking also gave him a knack for serendipitously finding his subjects. In Algiers to film the Pan-African Cultural Festival of 1969, he discovered that one of the most prominent American revolutionary activists, having jumped bail and fled the country, was also there; so the trip produced two films rather than one, The Pan-African Festival in Algiers and Eldridge Cleaver, Black Panther. In 1964, Klein was interested in filming the heavyweight championship boxing match between Sonny Liston and the up-and-coming underdog Cassius Clay, who had already joined the Black Muslims but had not yet changed his name to Muhammad Ali. Flying down to Miami to see the fight, Klein ended up sitting with Malcolm X, who smoothed his entrée into the Clay camp—enabling a far more intimate view of the preparation for and aftermath of the bout than he’d otherwise have had. In 1974, Klein filmed the so-called “Rumble in the Jungle,” the match in Kinshasa between Ali—who had been absent from the ring from 1967 to 1970 because of legal troubles stemming from his refusal to be drafted into the Army—and George Foreman, adding this color footage to his earlier black-and-white footage from 10 years earlier to create a new film, Muhammad Ali, the Greatest.

What Klein’s best films have in common (along with the one on Ali, I’d add The Pan-African Festival in Algiers and 1982’s The French, which is not, as the title might imply, about the French people but rather about a tennis tournament, the French Open) is that each one immerses the viewer in spectacle: Each film, in its own way, is about being caught in the crowd, absorbed in events—and about the pleasure and texture of that engagement.

Fellow filmmaker-photographer Chris Marker, with whom Klein had worked (along with Jean-Luc Godard, Agnes Varda, and others) on the 1967 collective film Far From Vietnam, said that a Klein film, paused anywhere at random, yields “a Klein photograph with the same apparent disorder, the same glut of information, gestures and looks pointing in all directions, and yet at the same time governed by an organized, rigorous perspective.” I’d simply reverse the statement: Klein’s films teach us that his photographs have always been incipiently cinematic, dynamically constructed with a kind of kinetics that always points forward in time, to an imaginable “next frame” in which things have moved along in an unpredictable way; they were never composed according to the criteria of stability and balance that photographers had inherited from painting. And for Klein, this dynamism always had an implicitly political charge, due to his desire to be drawn into the same energy as the collective rather than standing apart from it. “I’ve always done a kind of action photography, cramming bodies and looks into the frame that end up, somehow, falling into place,” he once said. But there’s probably something else. “When I photograph a march, almost any one, I find myself wanting to take part, even Chinese New Year’s…. It’s normal to want to join in a political demonstration that I relate to.” The feeling is infectious: Seeing Klein’s show might make you want to go out and join a demonstration too.