Larissa FastHorse’s Comedy Fake It Until You Make It Highlights the Absurdities of Ambition and Authenticity

Larissa FastHorse’s Comedy “Fake It Until You Make It” Highlights the Absurdities of Ambition and Authenticity

It’s a whirlwind of competition, chaos, and comedic discovery.

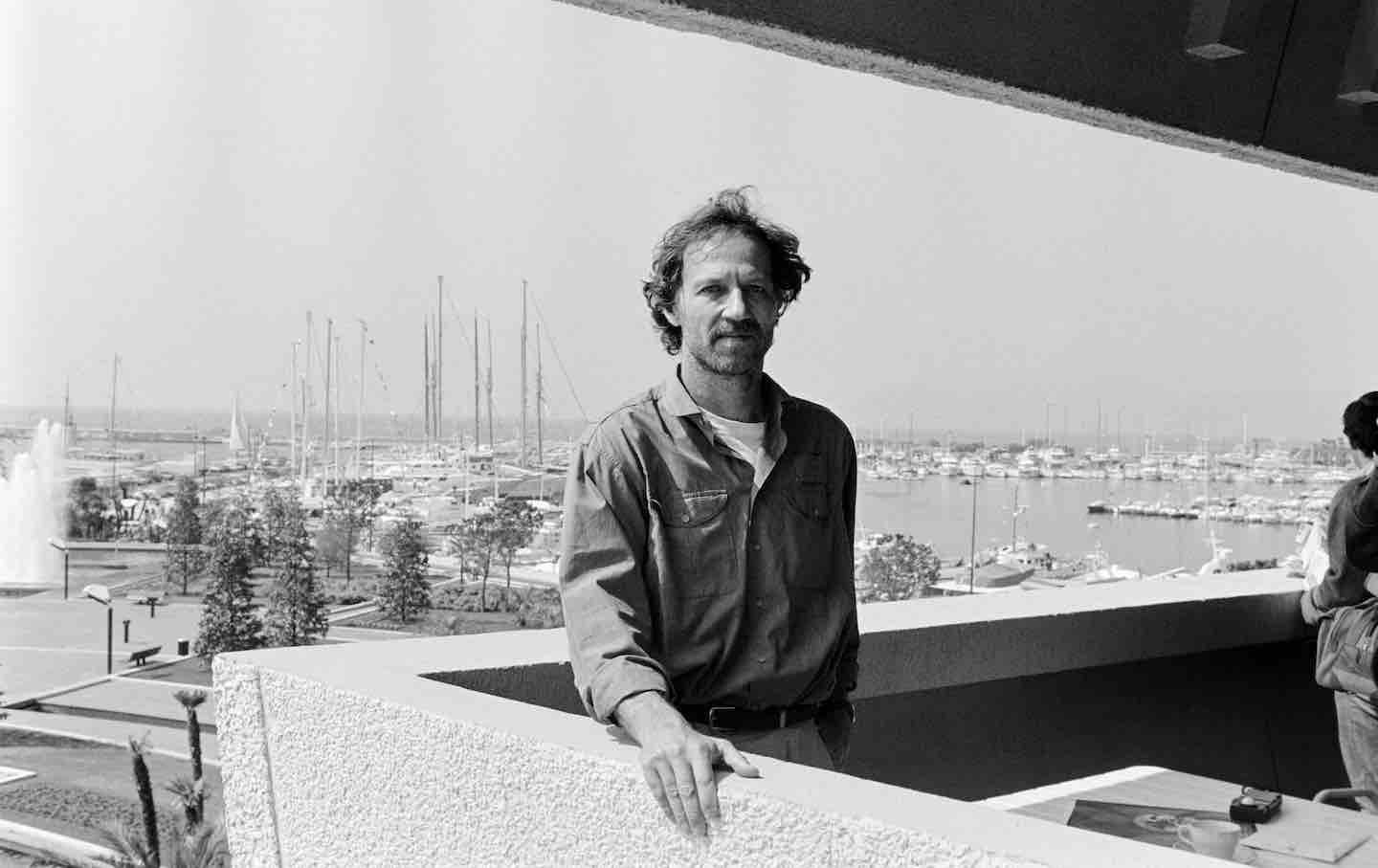

She is arguably the busiest writer of the moment—certainly in the theatre world. Larissa FastHorse just completed entertaining Los Angeles with her newest play, Fake It Until You Make It, which will be opening soon at the Arena Stage in Washington (starring Amy Brenneman). She’s been commissioned to do one for Public Theater in New York and for Broadway’s Hayes Theater, and she’s preparing a one-woman show about her career (which started as a ballet dancer) at the Seattle Rep. “I’m terrified,” she admits. “I’ve never done solo in my life, and my tutu days are behind me.”

We’re not finished. The show that elevated her career, The Thanksgiving Play (the first Broadway show written by a Native American woman), was recently mounted at Chicago’s Steppenwolf. She has also adapted and “Indigenized” (her word) a national touring production of the 1954 Broadway musical Peter Pan, adding more of Wendy and Tiger Lily and removing all red-face performances and demeaning lyrics. Over 300 productions have been done.

Did I mention she’s just sold two projects to television?

Fake It Until You Make It focuses on two nonprofits, sharing office space, competing for Native-American clients and grant money. It is a comedy about race-shifting (those who claim a different identity for personal gain) and wokeism. “I hope people are hearing some new ideas, or ideas in new ways,” FastHorse told me when we met in Santa Monica, where she lives with her sculptor husband. “So much of my work is about these issues, and I like to think this is a next step in the conversation.”

She has become something of a science nerd, fighting for full citizenship for Native Americans. She knows from her genomes. “What the government put on Native Americans was the concept of ‘blood quantum,’” she says, referring to the questionable system that estimates the amount of “Indian blood” in a person’s ancestry. “Meaning you have one native, one white, so you’re a certain percentage.” (FastHorse’s own father was Lakota, and her mother was white.) “It’s not how DNA should work,” she continues, “but we’re forced to live under old white assumptions about what Native Americans were—or were not—capable of navigating as we became a country.”

Interestingly, unlike many theatres of late, asking audiences to “honor those whose land we sit upon,” FastHorse’s current show does none of that. “We take all the announcements out at the theater,” she says. “Even the exit signs. It matters that when you walk in, it’s an indigenous space and an entire indigenous experience.”

“The play is even more timely now,” says Amy Forbes of Los Angeles’s Center Theater Group. “I loved that Larissa spares no one in her sharp and supremely funny take on do-gooders. And at the exact moment the federal government is slashing funds and protections for the kind of marginalized groups highlighted in the play.”

We have seen hope in other mediums. Reservation Dogs was a hit on television. Taylor Sheridan’s near monopoly on Paramount+ (where Yellowstone was birthed) also features Native American story lines. Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann was a big book, then a major film adapted by former Oscar-winner Eric Roth. And some in the theatre community are determined to continue what FastHorse has started.

“There is more and more extraordinary work being done by Native American artists throughout the American theatre,” says Bill Rauch, who runs the Perelman Performing Arts Center in New York. His initial season had a hit with a satirical show about Native Americans called Between Two Knees. “And there is a great hunger for Indigenous work from audiences. Larissa FastHorse brilliantly uses comedy to upend assumptions and to move all of us forward.”

I doubt if the current resident at the White House will attend. Maybe he can go with the senator he calls Elizabeth “Pocahontas” Warren.