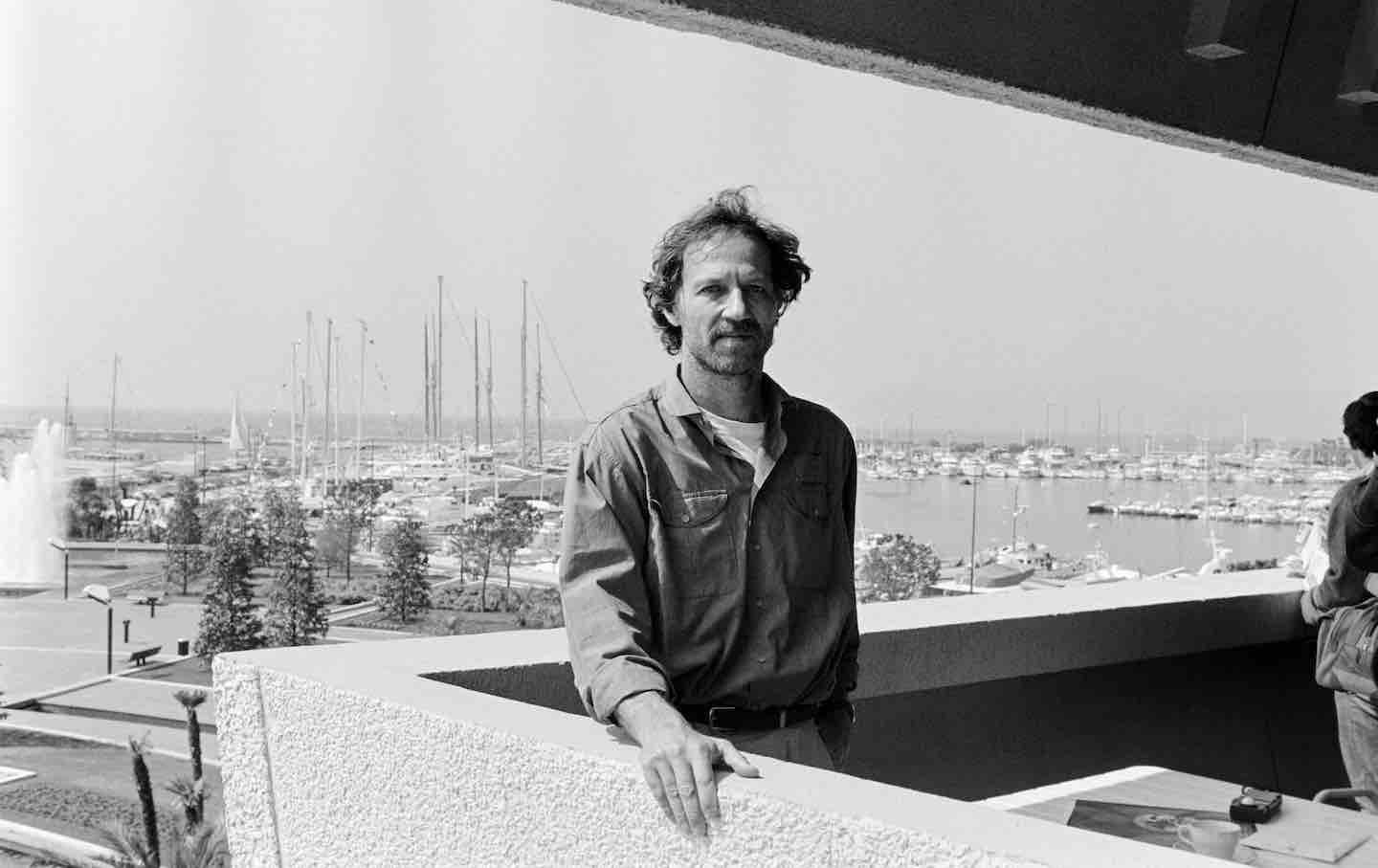

Brian Wilson (1942–2025) Outlived the Times He Helped Define

When the Beach Boys front man died, the obituaries described him as a genius. Which means what, exactly?

Anyone who grew up the 1960s grew up with the Beach Boys. The first time I heard them was on a transistor radio owned by one of the seventh-grade girls who lived in the farm town (pop. 72) where I was then marooned. I was in the second grade, and the song was “Surfin’ U.S.A.,” a rewrite of Chuck Berry’s “Sweet Little Sixteen.” (Berry is said to have first heard the single while he was in prison, serving a two-year sentence for violating the Mann Act.)

The Beach Boys were led by Brian Wilson. Indeed, Brian Wilson was the Beach Boys. He largely wrote, performed, and produced the recordings they made in the 1960s, from “Surfin’” in 1961 to “Do It Again” in 1968—the latter filled with nostalgia for a time in their lives that was then no more than five years in the past (a foretaste of their later career as purveyors of harmless memories)—and his voice, especially his falsetto, was a distinctive part of their sound.

Remembering Brian Wilson

But those facts—his melodies, his work in the studio (when rock gods die, their photographs usually portray them on stage; Wilson was shown at a sound board), even his vision of a distinctively American way of being as exemplified in the guileless lyrics and keening guitars of “I Get Around,” “Fun Fun Fun,” and “Be True to Your School” (my late father’s favorite; he was only seven years older than Wilson)—hardly explain Wilson’s legacy. When Wilson died recently, at the age of 82—when or where is still unclear—obituary writers leaped to describe him as “a genius.”

Which means what exactly?

For Wilson, it meant at least in part that he transcended understanding. In some ways, the music he made was puerile—the lyrics were often contemptible, the instrumental backing either undercooked or overwrought. Even masterpieces like “California Girls” and “Good Vibrations” are faintly ridiculous, more aspiration than achievement. Yet who can listen to “Caroline, No,” the concluding track—leaving aside the sounds of dogs barking and trains whistling—on the Beach Boys’ finest long-player, Pet Sounds, without being deeply moved?

Wilson was strange—probably mad—and it was his strangeness that contributed as much as his music to his reputation as a genius. Even in videos of the Beach Boys performing in the early 1960s, he appears to be searching for an exit. The breakdown that led to his forsaking live performance; the piano in the living-room sandbox; his panicked abandonment of Smile (the intended, and soaringly ambitious, follow-up to Pet Sounds); his wandering the aisles of his very own health-food store, the Radiant Radish, in a bathrobe—all became part of his legend.

And now Brian is dead, far outliving his brothers—the 39-year-old Dennis, who drowned in 1983 after a day of drinking, and the dutiful Carl, who died of cancer, then 51, in 1998—and most of his bandmates. (Of the Beach Boys most will remember, only his cousin Mike Love and his high school friend Al Jardine, survive.) More to the point, he had outlived the times he helped define. Yet the 45s and the best of the LPs—The Beach Boys Today!, Summer Days (and Summer Nights!!), Pet Sounds, even Smiley Smile, which was definitely not Smile—endure. Come summer, the title of one of the Beach Boys’ greatest-hits albums, Spirit of America, never seems truer. It is the music my Gen X wife and millennial daughters (and as one day, I am sure, my Gen Beta grandson will) all demand with their hot dogs and Cokes.

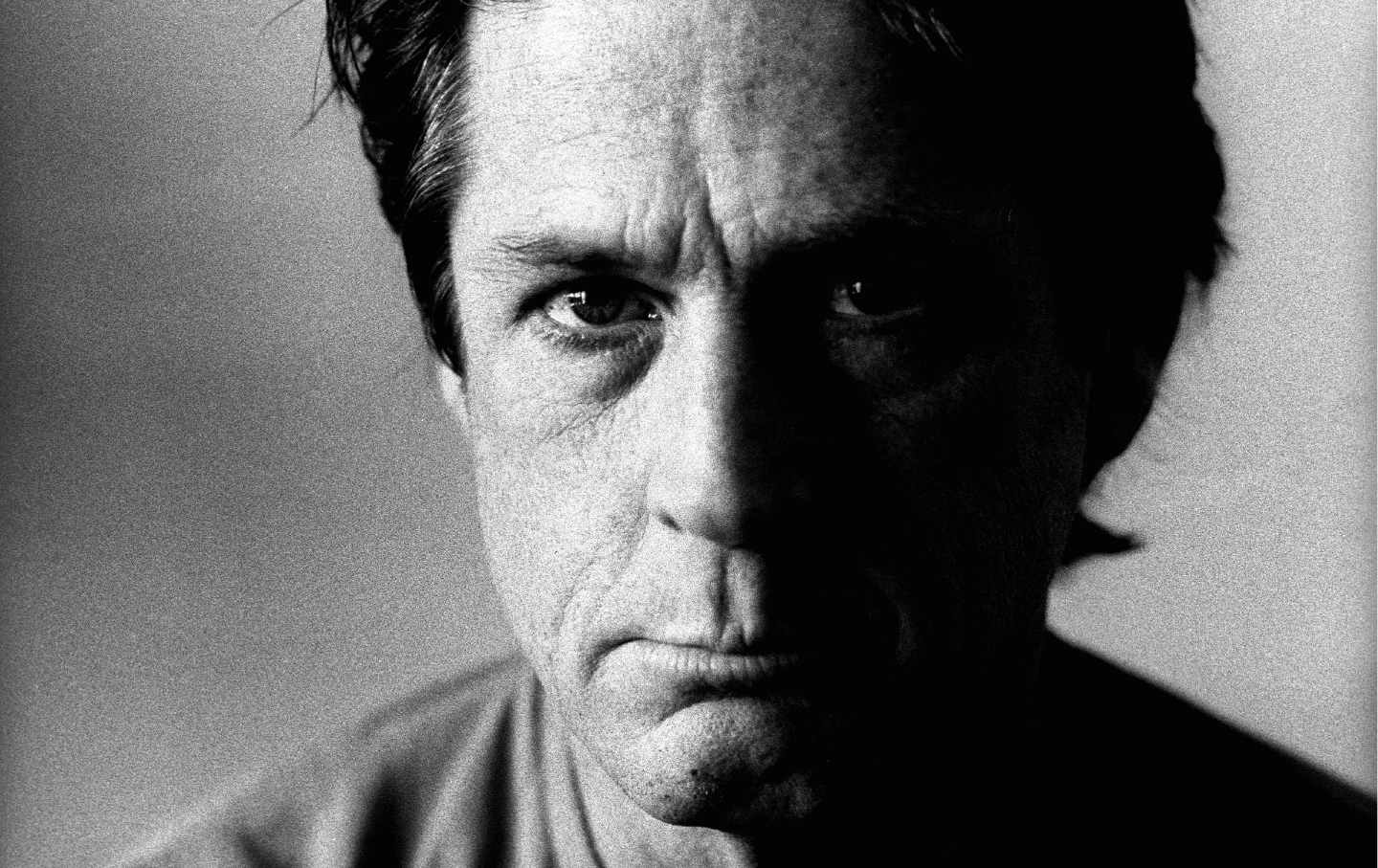

Of course, there was another America even then—as the recent death of another visionary, Sly Stone, serves to remind us. (Stone was also 82, make of that what you will.) Like Wilson’s Beach Boys, Sly and the Family Stone made music in the ’60s—“Dance to the Music,” “Everyday People” and “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)”—that was both joyful and, so baby boomers like me imagined at the time, inclusive. And yet, also like Wilson, there was a strangeness to Sly Stone as old as “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” The evidence was in the grooves of his early-’70s album There’s a Riot Goin’ On—along with Wilson’s “Surf’s Up” (a remnant of Smile released in 1971), a troubled foreshadowing of the failing dream we now all share.

Support independent journalism that does not fall in line

Even before February 28, the reasons for Donald Trump’s imploding approval rating were abundantly clear: untrammeled corruption and personal enrichment to the tune of billions of dollars during an affordability crisis, a foreign policy guided only by his own derelict sense of morality, and the deployment of a murderous campaign of occupation, detention, and deportation on American streets.

Now an undeclared, unauthorized, unpopular, and unconstitutional war of aggression against Iran has spread like wildfire through the region and into Europe. A new “forever war”—with an ever-increasing likelihood of American troops on the ground—may very well be upon us.

As we’ve seen over and over, this administration uses lies, misdirection, and attempts to flood the zone to justify its abuses of power at home and abroad. Just as Trump, Marco Rubio, and Pete Hegseth offer erratic and contradictory rationales for the attacks on Iran, the administration is also spreading the lie that the upcoming midterm elections are under threat from noncitizens on voter rolls. When these lies go unchecked, they become the basis for further authoritarian encroachment and war.

In these dark times, independent journalism is uniquely able to uncover the falsehoods that threaten our republic—and civilians around the world—and shine a bright light on the truth.

The Nation’s experienced team of writers, editors, and fact-checkers understands the scale of what we’re up against and the urgency with which we have to act. That’s why we’re publishing critical reporting and analysis of the war on Iran, ICE violence at home, new forms of voter suppression emerging in the courts, and much more.

But this journalism is possible only with your support.

This March, The Nation needs to raise $50,000 to ensure that we have the resources for reporting and analysis that sets the record straight and empowers people of conscience to organize. Will you donate today?