A beach at sunset. The sky is streaked peach and mauve, the wind cool and briny. A long line of dump trucks idles at the edge of the waves, each full of plastic—bags and milk jugs and floss containers, hair clips, shrink wrap, fake ferns, toys, and spatulas. Every minute, one of the trucks lifts its bed and deposits a load of trash into the sea.

The dump trucks aren’t real, but the trash is. No one knows exactly how much plastic leaks into the oceans every year, but one dump truck per minute—8 million tons per year—is a midrange estimate. Plastic waste usually begins its journey on land, where only 9 percent of it is recycled. The rest is thrown away, burned, or buried, left to wash into streams and rivers or to blow out to sea. Once in the ocean, the plastic drifts or sinks. The sun and the waves break it down into tiny particles that resemble plankton. Birds and fish and other sea creatures eat it and begin to starve. One analysis predicts that by 2050, the plastic in the oceans will outweigh the fish.

Some of the trash winds up in one of five current systems in the oceans known as gyres, where it forms a slowly circulating plastic soup. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is the largest of these zones, spanning an area twice the size of Texas between Hawaii and California, a merry-go-round of the remains of global consumption. Researchers have found small plastic shards and large objects in the gyre: hard hats and Game Boys and milk crates and enormous tangles of fishing nets, all swirling in a smog of microplastics.

Often inaccurately described as a solid island, the garbage patch has become a potent symbol of the world’s plastic problem, alongside viral photos of a sea horse clutching a Q-tip, a sea turtle with a straw wedged deep in its nostril, and a dead adolescent albatross with a stomach full of jewel-like plastic shards. These images have helped raise the alarm about plastic waste around the world, inspiring responses ranging from weekend beach sweeps to the Ocean Cleanup, a controversial and expensive effort to collect the trash in the Great Pacific gyre. Even the corporations that produce plastics have grown alarmed. In January, dozens of companies including Dow, ExxonMobil, Chevron Phillips, and Formosa Plastics Corporation announced the Alliance to End Plastic Waste, with an initial commitment of $1 billion to fund recycling and cleanup.

But those same petrochemical giants are about to make the plastic problem worse. Companies are investing $65 billion to dramatically expand plastics production in the United States, and more than 333 petrochemical projects are underway or newly completed, including brand-new facilities, expansions of existing plants, vast networks of pipelines, and shipping infrastructure. This is a sharp reversal of fortune for American plastics manufacturers. Just over a decade ago, major plastics makers shed tens of thousands of jobs as cheaper operating costs in Asia and the Middle East lured production overseas. Now, thanks to the fracking revolution, producing plastic has become radically cheaper in the United States, leading to a glut of raw materials for its creation. The economic winds have shifted so profoundly that petrochemical companies have declared a “renaissance” in American plastics manufacturing. In turn, plastic is becoming an increasingly important source of profit for Big Oil, providing yet another reason to drill in the face of climate change.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The expected result of all this investment is a spike in the amount of plastic produced globally, as manufacturers in Asia and the Middle East ramp up their own production—with capacity increasing by more than a third in the next six years alone, according to an estimate from the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL). Most of this new plastic will be sent to developing countries with waste infrastructure ill-equipped to handle it. “If you’re going to increase production of plastics—double it in the next 15 years—you’re going to see an increase of unrecyclable plastic products and packaging going to the more remote parts of the world, where there is still no plan for efficient recovery,” said Marcus Eriksen, a scientist and former Marine who co-founded the 5 Gyres Institute. Against this backdrop, investing $1 billion in trash collection is like trying to empty a bathtub with a teaspoon while the tap is on full blast.

But plastic—and its fossil-fuel precursors—leaves a mark long before bags and bottles and Q-tips scatter across fields or wash into the oceans. Communities all along the supply chain will feel the impacts of the American plastics renaissance. What the industry describes as a bright new economic opportunity, others see as a looming disaster. “For too long, one of the most invisible aspects of the plastics crisis has been the impacts of plastics on communities who live in the shadows and along the fence line of plastics refining and manufacturing,” said Carroll Muffett, CIEL’s president and CEO. “These people are experiencing the impacts of our plastic planet in a way that is more immediate and more severe than just about anybody else in the world.”

In the United States, the front of the plastics boom runs along the Gulf Coast from Texas to Louisiana, and through the upper Ohio River Valley, which spans Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. It’s made up of small communities that often had little say in their role in the new infrastructure build-out, with decisions made largely behind the scenes by politicians and corporate behemoths. Until recently, many people had no idea that their towns would soon become the knots connecting an immense plastic net thrown across the country.

In May 2017, Donald Trump made his first overseas trip as president, to Saudi Arabia. He waved a sword during a ceremonial dance, accepted lavish gifts—including a portrait of himself and a robe lined with white tiger fur—and signed a $110 billion arms agreement. Meanwhile, in a mint-and-gold-colored room within the Saudi royal court, executives struck their own deals. Among them were Darren Woods, the CEO and chairman of ExxonMobil, and Yousef Al-Benyan, CEO of the Saudi Basic Industries Corporation (SABIC), one of the world’s largest producers of petrochemicals. With Trump, Saudi King Salman, and then–US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson (a former Exxon CEO) looking on, Woods and Al-Benyan shook hands on a joint venture to build what will be the largest plastics facility of its kind, on Texas’s Gulf Coast.

Long before the deal was immortalized with glitzy photo ops, it was known as Project Yosemite—a code name designed to keep the initiative secret while its backers scouted sites. What the two companies wanted to build is known as a “cracker,” a facility that uses heat and pressure to crack apart molecules of ethane gas so they can be reconfigured as ethylene and later polyethylene, the building block for a wide range of plastic products, from packaging to bottles. Once an unwanted by-product of oil and gas fracking, ethane flowing from Texas’s Permian Basin and Eagle Ford Shale is now prompting a massive build-out of petrochemical infrastructure—pipelines, crackers, polyethylene plants, tanker terminals—along the Gulf Coast from St. James, Louisiana, to Corpus Christi, Texas.

In 2016, with help from Texas Governor Greg Abbott, Exxon found a site for Project Yosemite on 1,400 acres of farmland north of Corpus Christi. By the time residents of two neighboring towns learned of the massive project, county commissioners had already rezoned the farmland and were eagerly courting the oil giant. Soon Exxon was seeking $1 billion in tax breaks from the county and local school district. “That’s when people woke up,” said Errol Summerlin, a retired Legal Aid attorney who lives a few miles from the Exxon site, in the town of Portland. “Bingo. We started the battle then.”

A trim man with slightly stooped shoulders and a gravelly voice, Summerlin has lived in the same single-story white-brick house in Portland for 34 years. When I met him there in early January, he laid out a large map across his glass-topped dining table. With his finger, he traced the outline of Copano and Aransas bays to the north, where briny waters provide habitat to shrimp and oysters, redfish and black drum, roseate spoonbills and whooping cranes, and where billions of gallons of wastewater from the cracker will discharge. He pointed to an industrial corridor established in recent years on the north side of Corpus Christi Bay, where the flare from a natural-gas plant flickers incessantly. “That’s Cheniere. You’ve got Sherwin Alumina, you’ve got Oxychem, Flint Hills…,” he said, ticking off various industrial sites. Across the water, a narrow shipping channel runs like a vein along Refinery Row, a corridor of round white storage tanks and towers that puff out columns of white and gray fumes.

When Summerlin learned that hundreds of acres of farmland would be turned into an entirely new industrial zone for the cracker plant, he was disturbed. “Industry has been inching itself closer and closer to Portland,” he explained. Plotted on a map, the rectangle of land where Exxon plans to build is nearly as large as Portland and about twice the size of neighboring Gregory, a low-income, largely Hispanic community. While county officials and members of local business groups boasted of some 600 permanent jobs promised by Exxon, Summerlin worried about air and water pollution from the plant. According to Exxon’s requested air permit, the facility will emit sulfur dioxide, volatile organic compounds, and nitrogen oxides, which can combine to form ozone smog; carcinogens, including benzene, formaldehyde, and butadiene; and other particulate matter. The health risks of these emissions include eye and throat irritation, respiratory problems, and headaches, as well as nose bleeds at low levels and, at high levels, more serious damage to vital organs and the central nervous system.

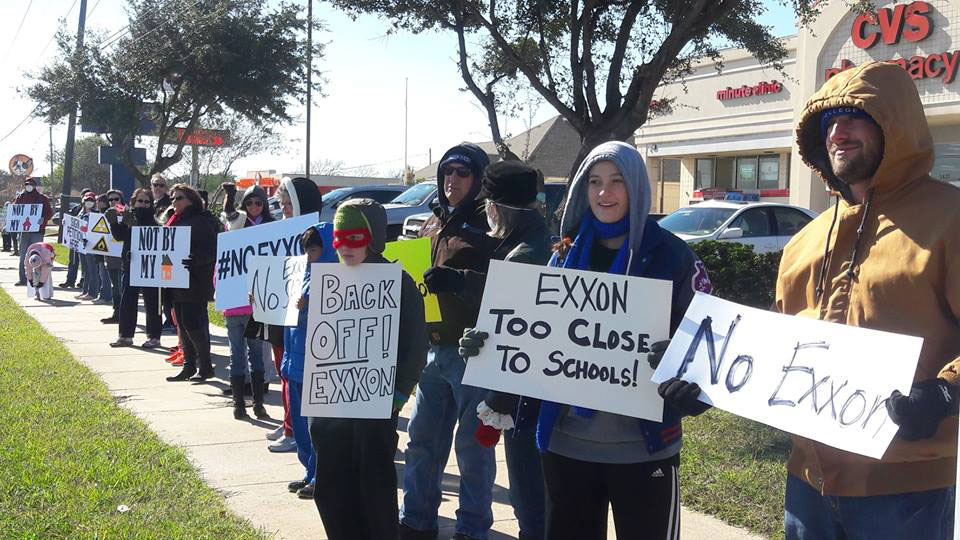

In late 2016, Summerlin and other concerned residents joined a newly formed group called Portland Citizens United, which sought initially to collect information about the proposed plant and later to try to stop the project, or at least convince Exxon to relocate to an area already given over to heavy industry. First they challenged the rezoning, which had been done in violation of open-meeting laws. That set the project back a few months. The Portland City Council unanimously adopted a resolution opposing the site, on the grounds that it was too close to public schools—but because the site lies just outside city limits in unincorporated San Patricio County, the resolution amounted to a toothless plea. Now, the Texas Campaign for the Environment and the Sierra Club, working on behalf of Portland and Gregory residents, are contesting the air-quality permits that Exxon requested from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. Summerlin is not naive about the prospects of this effort: The commission is notoriously friendly to industry and, as far as Summerlin knows, has never denied a permit—certainly not to Exxon, one of the largest employers in the state. Nevertheless, Summerlin said, “I’m doing my best to slow the suckers down.”

We got into Summerlin’s car and drove through Portland’s sleepy neighborhoods, past the high school and middle school, then hooked a left on the straight, flat road that runs next to the site. Once planted with cotton and sorghum, the plot is a weedy brown rectangle two miles long and a mile wide, ringed by a tall wire fence and newly installed power lines. Summerlin drove slowly along the fence line, pointing to the outflow ditches where stormwater will be flushed out to the bays. In the fields stretching out to the north and east, a fleet of windmills stood at attention, arms spinning lazily. We passed a small pasture of Texas longhorns, which raised their heads to look at the car. Sandwiched between houses, with industrial smokestacks looming on the horizon, the cattle appeared lost. Further down the road, limp plastic bags dotted a fallow field of brown stalks like giant tufts of wet cotton.

As Summerlin learned more about the facility, he grew increasingly alarmed by its scale and started to feel like the community had been misled. In addition to the steam cracker, which will produce 1.8 million tons of ethylene every year, Exxon and SABIC are building three units to make polyethylene and monoethylene glycol—which can be turned into antifreeze, latex paints, and polyester for clothing—as well as a rail yard where plastic pellets will be loaded onto trains bound for ocean ports and then shipped to Asia and Latin America. The facility needs a new road to transport components to build the plant, as well as a cargo dock and marine terminal. “They’re all lauding this as a game changer—and it is, in a bad way,” Summerlin said. “It transforms the whole area.”

Such infrastructure is just a small part of what oil and gas companies have planned for the Gulf Coast. Across Texas in recent years, more than 8,000 miles of pipeline have been laid down to carry oil, gas, and natural-gas liquids (which include ethane) from the Permian Basin and the Eagle Ford Shale to the coast, where dozens of new petrochemical projects are in the works. Exxon alone is planning to spend some $20 billion over a decade on its “Growing the Gulf” venture, a suite of petrochemical projects that includes the cracker outside Portland; another cracker at the company’s chemicals complex in Baytown, near Houston; and an expansion of its plastics plant in nearby Beaumont. Other development is being driven by Congress’s lifting, in 2015, of 40-year-old restrictions on crude-oil exports. With oil and natural-gas production surging, companies are eager to get their products overseas. Recently, the Port of Corpus Christi put forward plans to build new terminals for massive oil tankers, which raised hackles in Port Aransas, a beach town close to the proposed site that depends on tourism and fishing, both of which could be disrupted by ships nearly the length of four football fields coming and going.

All of these new facilities will require water; Exxon’s cracker alone will consume 20 to 25 million gallons per day, more than all the water currently used each day in San Patricio County’s water district. But the area is prone to drought. The Port of Corpus Christi has plans to build a seawater-desalination plant on Harbor Island near Port Aransas, which could lead to discharges of extremely salty water back into the bays that serve as nurseries for shrimp and fish. The development is also vulnerable to hurricanes. When Hurricane Harvey swept across Houston in 2017, many chemical plants shut down, releasing an estimated 1 million pounds of excess toxic emissions that drifted into neighboring communities.

But with little resistance from regulators, companies are plowing ahead with new development. Recently, the Port of Corpus Christi purchased 3,000 acres to the west of Portland, which Summerlin expects will be leased for other petrochemical projects. “We know what’s going on,” he said, “but nobody’s telling us.” A recent planning document showing the port’s new tract of land listed code names for two new undisclosed proposals: Projects Falcon and Dynamo.

About 80 miles up the coast from Portland in Point Comfort, tiny translucent pellets the size of lentils burrow into the muck and weeds at the edge of a sluggish creek. Further out, the pellets mingle with aquatic plants, floating together in whorls like confetti. Oystermen and anglers working in bays nearby find them inside oyster shells and in the guts of fish.

Diane Wilson has been collecting these pellets for years. The “nurdles,” as they’re often called, have taken over her barn, which is stacked with bags of them, and 30 years of her life. A former commercial shrimper, Wilson is locked in a protracted battle against the source of the pellets: Formosa Plastics, a Taiwanese company that manufactures polypropylene, PVC, and other petrochemicals at a 2,500-acre complex along Cox Creek. In 1994, Wilson tried to sink her shrimp boat in a nearby bay to protest the chemical-laden wastewater discharges from the plant. Almost daily over the past four years, she and a handful of volunteers, some of them former Formosa employees, have gone out in kayaks and waders to collect evidence of the ongoing pollution. Although the US Environmental Protection Agency and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality have fined Formosa repeatedly for various air- and water-quality violations, the nurdles continue to wash into the creek. Wilson is currently suing Formosa, asking a federal judge to fine the company $173 million and order an end to the dumping.

In Louisiana’s St. James Parish, a majority-black community that spans the Mississippi River west of New Orleans, Formosa’s plans to build a $9.4 billion plastics complex have drawn outrage from residents already hemmed in by dozens of chemical facilities and refineries. Cotton, sugar, and indigo plantations once lined the river; more recently, lifetime resident Sharon Lavigne remembers, her grandfather caught shrimp in the Mississippi River and picked figs and pecans from the trees in their yard. Now, St. James hosts more than a dozen industrial sites—part of a corridor stretching from Baton Rouge to New Orleans that is often referred to as “Cancer Alley.”

Formerly designated for agricultural uses, the land for Formosa’s new plant—which sits in a district that is more than 85 percent black—was redesignated as a “future industrial” zone in a planning document published in 2014, a decision that residents and environmental groups say was made with inadequate community input. A section of the planning document focused on the parish’s history quotes a 1950s-era historical account that describes the early 1800s in St. James as an “era of fabulous plantation life” and “luxurious living,” during which “acreage was counted by thousands and slaves by hundreds.” Aside from demographic figures, that is the report’s sole mention of the area’s black communities. Anne Rolfes, founding director of the environmental-justice group Louisiana Bucket Brigade, called the planned development in the area one of “the most disgusting racial situations I’ve ever seen.”

Like many St. James residents, Lavigne can list a number of friends and relatives who have died from cancer or been sickened by respiratory conditions. After she learned about Formosa’s plans to build yet another facility, Lavigne, a teacher who lives about a mile and a half from the proposed site, started a group called RISE St. James. At first, it consisted of 10 people meeting at her house. The group has since grown to a few dozen; they’ve held marches and shown up at public meetings to oppose Formosa and other plants. “We go to the meetings, we express our concerns, and people just look at us as though we’re nothing,” Lavigne told me. In December, activist Cherri Foytlin brought a permit hearing for the facility to a standstill when she told government officials, “You don’t give a shit about brown and black people.” A single mother of three who lives in St. James Parish because she can’t afford a home closer to New Orleans told regulators, “I feel like I’m trapped. I feel like I don’t have anywhere to go. I can’t get away from the pollution. I’m surrounded by it.” Two months later, the state approved one of Formosa’s critical permits.

For a long time, communities like St. James and people like Diane Wilson fought lonely battles against the petrochemical industry. The Break Free From Plastic movement, a coalition of more than 1,400 organizations, is working to connect these various localized struggles, from communities in West Texas impacted by fracking to neighborhoods in the Philippines that are awash in plastic trash. Carroll Muffett of CIEL, which is a member of the coalition, said, “They realize they’re all fighting different aspects of the same industry and the same problem.”

The story that the petrochemical industry tells about its products is not about pollution. It’s a story of an innovation-driven manufacturing comeback, one that will create jobs at home and provide essential products to meet a growing demand overseas. “We are using new, abundant domestic-energy supplies to provide advantaged products to the world,” Exxon CEO Darren Woods said at a 2017 energy conference regarding the company’s planned $20 billion investment in petrochemical infrastructure along the Gulf Coast. “The advent of plastics has benefited the world,” Graham van’t Hoff, executive vice president of Shell’s chemicals division, wrote in January. Solar panels, wind turbines, and electric vehicles all use plastic components, he continued. The plastic products that account for the bulk of rising demand in developing countries, however, are not life-saving medical devices or specialized vehicle components. They aren’t even really products in their own right. According to the International Energy Agency, “the single largest source of plastic demand” is packaging—the shrink-wrapping around a box of mushrooms, the tiny sachets containing a single wash of shampoo—much of it thrown away as soon as it is removed. This has historically been the plastic industry’s profit model: “The future of plastics is in the trash can,” Lloyd Stouffer, the editor of the trade journal Modern Packaging, declared in 1956. Now, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, about a third of packaging ends up as trash. The environmental damage it causes and the greenhouse gases emitted during its production together cost some $40 billion annually—“exceeding the profit pool of the plastic packaging industry.” The petrochemical industry sees this largely as the fault of waste-collection systems in poor countries. “I find the issue of unmanaged plastic waste deeply concerning,” van’t Hoff wrote in January. But, he added, “The challenge is not with plastics themselves. It is what happens after people use them. In some places, waste and recycling infrastructure is inadequate…. As a producer of petrochemicals and plastic resin, we cannot directly control the amount of plastic waste that gets into [the] environment.”

Plastics producers have responded to growing public pressure by offering some support for cleanup efforts. “We believe we have a role in fixing it,” said Steve Russell, vice president of plastics for the American Chemistry Council, which represents petrochemical companies, speaking of the plastic-waste crisis; he added that current funds for the industry’s Alliance to End Plastic Waste are “a start point.” But many environmental advocates see these efforts as greenwashing. Marcus Eriksen of the 5 Gyres Institute said that many of the solutions put forward by the industry require costly technology that will take years—if not decades—to scale. “They’ve been very effective in making the public think that recycling is key, and that it’s the burden of the citizen, of the community, of the government to manage waste,” Eriksen continued. “Globalization is still going to send unrecyclable materials to more remote parts of the world that can’t employ the solutions that industry proposes, because they’re expensive.”

Environmental groups like those in the Break Free From Plastic movement are increasingly calling for a prevention-focused strategy, in which companies stop making materials designed to be used only once and pay the full cost of collecting and recycling plastic products. NGOs, academics, even the corporate consulting group McKinsey have embraced the concept of a “circular” plastics economy, in which products flow through a closed loop rather than “leaking” out. The circular model depends on improving the economics and technology of recycling and on fundamentally redesigning materials to replace single-use plastics with biodegradable or recyclable alternatives. A true circular model also requires reducing and eventually eliminating the amount of plastics created from fossil fuels—by developing alternative feedstocks from renewable sources, and by supplanting virgin feedstocks with recycled content.

Running in the opposite direction are the major oil companies, who have placed big bets on their role as plastics producers. For oil giants like Exxon and Shell, plastics and other chemicals represent an increasingly significant source of profit—one that a circular-economy approach would threaten. “While increased recycling of plastics represents a gain in circular-economy terms, it is less good news for oil-resource-holding countries and oil companies, which will lose part of a source of future demand growth,” McKinsey analysts wrote recently. According to the International Energy Agency, “petrochemicals are rapidly becoming the largest driver of global oil consumption,” picking up the slack as efforts to curb emissions and increase efficiency limit other sources of demand. In 2015, while only 10 percent of Exxon’s revenue came from its chemicals division, chemicals accounted for more than a quarter of its profits.

As climate change forces a reckoning with fossil-fuel consumption, plastics offer another incentive to keep drilling. “Investing in chemicals is part of our strategy to thrive through the energy transition,” wrote Shell’s van’t Hoff. The billions invested in new petrochemical infrastructure and local markets for ethane could help keep shale drillers—many of whom have been bleeding money—afloat. (According to the US Energy Information Administration, the high content of ethane and other natural-gas liquids in “many shale plays has made it economical for operators to continue to aggressively develop…shale gas resources during periods of low natural gas prices.”) The boom in plastics “will perpetuate a fossil fuel economy that underpins both the climate crisis and the plastics crisis,” concludes a 2017 CIEL report, “while impacting frontline communities and the wider public at every stage of its toxic lifecycle.”

Early one morning last September, a gas pipeline near Terrie Baumgardner’s home in western Pennsylvania exploded, turning the sky the color of dirty orange sherbet. Flames shot 150 feet into the air, destroying a house and sending several families scrambling to evacuate. Driving down the interstate days later, Baumgardner could make out a patch of scorched earth where the gas had burned itself out.

Two days later, officials in the nearby township of Independence voted to repeal a rule mandating that pipelines be built at least 100 feet away from homes and 500 feet from parks, schools, and hospitals. Eliminating the ordinance eased the way for the Falcon Pipeline, a 97-mile project that will carry ethane from the Marcellus Shale to a new cracker being built by Shell on the banks of the Ohio River in Beaver County. To Baumgardner, a retired college instructor and member of a local nonprofit called the Beaver County Marcellus Awareness Community, the elimination of the pipeline-setback rule was yet another example of state and local officials’ rush to accommodate Shell.

The cracker, slated to start operating in late 2021 or early 2022, will be the first to open outside the Gulf Coast in decades. But it’s just one of several projects underway in the Ohio River Valley as corporations, state officials, and members of the Trump administration look to transform the region into a brand-new petrochemical corridor. A Thai company has proposed a cracker farther down the Ohio River in Belmont County, Ohio, and the industry and its political allies want to build a massive storage hub to hold as much as 100 million barrels of ethane and other natural-gas liquids beneath West Virginia, and possibly Pennsylvania and Ohio as well. The US Department of Energy is considering a $1.9 billion loan for that project, which Energy Secretary Rick Perry has described as a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for this country.”

To many people in northern Appalachia, petrochemicals look like the answer to the economic problems created by the collapse of steel and coal. Shell has helped drive that narrative, commissioning a study that predicted the cracker would produce $15 to $19 billion in regional economic activity in southwestern Pennsylvania over four decades. Although some economists have disputed the methodology that produced this rosy projection—for instance, it assumes that every job created at the plant will lead to 13 elsewhere, and omits the cost of a historic $1.65 billion tax break the state gave Shell—it was welcome news in Potter Township, where Shell is building its facility: 500 jobs there vanished when a zinc-smelting facility closed in 2014, leaving hundreds of acres contaminated with lead and arsenic. Shell promised to clean up the site and pledged hundreds of thousands of dollars for local historic-preservation projects.

But to others, including Baumgardner, whatever economic benefits the cracker provides are far outweighed by the risks of large-scale petrochemical development. Pennsylvania has a long history of damage related to extractive industries, from the Donora smog of 1948, when a poisonous air inversion killed 20 people and sent some 6,000 others to the hospital, to the fragmented disasters of fracking: toxic-waste ponds, ruined property values, lingering illnesses. “This area of the Ohio River Valley, and other areas that have had a lot of experience with resource extraction, they follow this boom-bust cycle. When you’re in a bust phase and you lose jobs, there’s a lot of momentum: ‘Well, we need to attract industry to bring these jobs back,’” said Jennifer Baka, an energy geographer at Penn State. “We can’t think outside of the box and think about what an alternative-energy future might be, because we’re so familiar and accustomed to the existing fossil-fuel economy.”

Southwestern Pennsylvania suffers from some of the poorest air quality in the nation, according to Matthew Mehalik, the executive director of the Breathe Project, which works on air-pollution issues. “If you consider that backdrop—[that we] already have a serious air-quality problem—the potential to add more burden to our airshed will only make things worse,” he added. One estimate puts the health-care impacts over a 30-year period from the Shell plant and two other crackers proposed in the region at $616 million to $1.4 billion in Beaver County alone, and up to $8.1 billion nationally.

Critics of the projects also argue that regulators and communities are unprepared for the scale of development that is now underway. Lisa Graves-Marcucci, the Pennsylvania coordinator for the Environmental Integrity Project, is particularly worried about what she describes as “piecemeal, egg-slicer” permitting, in which projects like Shell’s cracker are considered in isolation, obscuring the web of industrial infrastructure—drilling sites, compressor stations, storage hubs, pipelines—that goes along with them. Even some people in the industry have suggested that communities might not be fully aware of what’s coming. “I think the magnitude of some of these projects that we’re talking about here is hard for a lot of us and a lot of our communities to wrap their heads around,” said Chad Riley, the CEO of the Thrasher Group, an engineering firm with projects in oil and gas fields, speaking at an industry conference in 2018 that was attended by reporter Sharon Kelly.

Ultimately, the fate of a facility that will affect the whole region was largely decided by three supervisors in tiny Potter Township, population 496. “Decisions have been made at higher levels of government, or sometimes in these small communities…that will forever change our region,” Graves-Marcucci said. “Does that mean we’ve signed over our entire future to this constant need to drill more and frack more? Are we stuck on this treadmill of plastics?”

Pennsylvania’s northeastern neighbor has taken a different approach. New York banned fracking in 2014 and, a year later, unveiled a clean-energy initiative that established some of the most aggressive energy-transition goals in the country. In 2018, Governor Andrew Cuomo announced a $1.5 billion investment in renewables projects across the state, with a goal of creating 40,000 clean-energy jobs by 2020.

For a long time, Terrie Baumgardner didn’t think much about what would come out of Shell’s ethane cracker. Early on, she heard that the plant would produce plastic pellets, perhaps to fill stuffed animals. “But I don’t think we realized at that point what a hazard plastic was for us and for the planet,” she said. “It’s only lately become a ‘for what?’ question—why are we doing this?” She continued: “Our leaders said, ‘Here comes an industry and it can get people jobs.’ And it was a backward-looking industry, but they didn’t see it that way.”