In one of Teiko Yonaha-Tursi’s earliest memories, she’s on a mission that gets interrupted. Walking barefoot through a lush green field in Itoman, Okinawa, Yonaha-Tursi—then just Teiko Yonaha—stops suddenly and starts jumping up and down. Her little legs were attacked by fat red ants.

“Okinawa is a very hot and humid island,” said Yonaha-Tursi, now a grandmother, retired social worker, reporter, and goodwill ambassador for Okinawa who lives in New Jersey. “So all these dead bodies became fertilizers.” Corpses decaying after the Battle of Okinawa offered extra nutrients, so the grasses were thriving, obscuring the ant colony that she had trampled.

She was out bone-spotting, part of a search group looking for salvageable remains from the three-month World War II battle that killed an estimated 100,000 Okinawan civilians—up to a third of the island’s population. “[The bodies] didn’t bother me,” Yonaha-Tursi said, “because we lived in the caves,” like many Okinawans who evacuated their homes to shelter in cramped subterranean quarters near the end of the war. Japan had concentrated its military forces in Okinawa in hopes that the United States would invade there, avoiding the mainland, and the plan worked. Although devastating, the battle was only one episode in the long history of the island’s abuse at the hands of two empires: Japan and the United States.

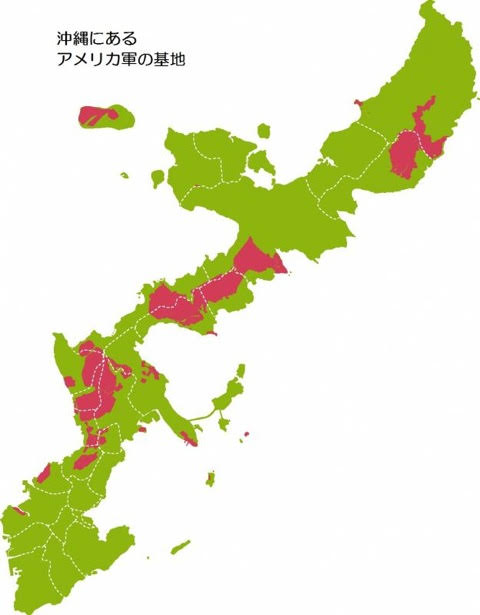

The Battle of Okinawa ended in 1945, but the US military never left. After the war’s conclusion, the United States occupied Okinawa until Japan and the Allied Powers signed the 1951 Treaty of San Francisco, which gave the United States jurisdiction over Okinawa for 20 more years. In that time, the Pentagon established dozens of bases on the island, 32 of which are still operating. At just 877 square miles—about two-thirds the size of Rhode Island—Okinawa Prefecture accounts for just 0.6 percent of Japan’s land mass but contains more than 70 percent of the country’s US-occupied territory.

If it sounds as though Okinawa probably can’t fit any more bases, that’s because it can’t. Nevertheless, a new one is going up in Henoko-Oura Bay near Nago, the town where Yonaha-Tursi was born. The construction won’t add to the already high number of bases but rather replace one: The bay is the relocation site for the detested Futenma Marine Corps Air Station, currently in populous Ginowan and a cause of distress to residents, who have lived with the roar of Futenma’s planes since the end of the war. Because Okinawa is already so full of bases—they cover about 15 percent of the island—the Japanese government, in compliance with the US Defense Department, is extending the island’s eastern edge. In order to do it, landfill is being dumped into Henoko-Oura Bay, where two coral reefs and thousands of aquatic species—nearly 300 of them endangered—currently live.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Dugongs are like manatees, but a little smaller. And rarer: Both are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species, and in Japan, dugongs are critically endangered. They live almost as long as humans (about 70 years), and they reproduce infrequently, with female dugongs typically calving every three to seven years.

In 1997, Japan’s Mammalogical Society estimated that there were fewer than 50 dugongs remaining in the waters surrounding Okinawa. The last official count, based on surveys conducted between 2009 and 2013, estimated that those 50 dugongs may have been reduced to three, at least one of which was a calf. But dugongs are hard to spot. They’re shy and sensitive to sound and light, so in order to find one, an observer needs patience, training, and a keen eye. A general lack of commotion helps.

The Department of Defense knows all about this, as it made clear in a brief submitted to the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in March 2019. It was, in the Pentagon’s own words, “the second appeal in a long-running suit involving plans to relocate a United States Marine Corps air station in Okinawa, Japan.”

In 2003, when the dugongs’ numbers were surely higher, a group of plaintiffs including four US and Japanese organizations—the Center for Biological Diversity, Turtle Island Restoration Network, Japan Environmental Lawyers for Future, and the Save the Dugong Foundation—and three Okinawan private individuals sued the DOD to prevent construction in the bay. The surveys from 2009 to ’13 have identified dugong feeding trails in the area designated for the Futenma replacement facility. Construction for the new Futenma Air Base has started, stopped, and started again because of the lawsuit—though the plaintiffs make up only one small faction of local and international opposition to the base.

“I think civilian action has been strong,” said Hideki Yoshikawa, an anthropologist and adjunct lecturer at the University of the Ryukyus, Meio University, and the Okinawa Prefectural University of Arts. Yoshikawa is the international director of the Save the Dugong Campaign Center and the director of the Okinawa Environmental Justice Project, and while he’s not a plaintiff, he got involved with the lawsuit in 2007, working, naturally, on the dugongs’ side.

“Poll after poll conducted by newspapers has constantly shown 70 percent of people oppose the plan,” Yoshikawa said. A referendum in February with an unusually high turnout confirmed those numbers: 72 percent of Okinawan voters rejected the Henoko-Oura Bay construction. “The central government,” The Japan Times reported after the vote, “has said it will ignore the result and go ahead with construction.”

“It’s an injustice,” Yoshikawa said. “The Japanese government wants to keep US military bases in Okinawa, not in mainland Japan. If the bases were distributed equally on mainland Japan, I think it wouldn’t feel that much like discrimination.”

To make sense of the disproportionate concentration of bases in Okinawa, activists invoke a term that many US readers will find familiar. “This is like NIMBY,” said Shinako Oyakawa, a co-director of the Association for Comprehensive Studies of the Lew Chewans. (Lew Chew is another name for the Ryukyu Archipelago, which stretches from Japan’s Kyushu to Taiwan and includes Okinawa.) Like most instances of the phenomenon, NIMBY-ism in Japan is rooted in social inequity. In Okinawa’s case, it’s a holdover from Japan’s imperial past.

The Ryukyu Islands were home to a prosperous independent trading kingdom for centuries, though it was long a member of China’s tributary system and was partly occupied by Japan starting in the early 17th century.

In the 1870s, Japan and China were engaged in a fierce debate over the national identity of the Ryukyuan people, which former US president Ulysses Grant mediated as a private citizen. His judgment legitimized Japanese claims of “ethnic affinity” with the Ryukyuan people, smoothing the process for Japan to annex a large portion of the Ryukyu Islands. In the discussions, “Ryukyuan voices really were not being heard,” noted Mark McNally, a professor of history and a member of the Center for Okinawa Studies at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. Nevertheless, with Grant’s help, the Ryukyu Kingdom became Okinawa Prefecture in 1879.

“Japan has a long history of prejudice against Okinawans,” said Rob Kajiwara, a Hawaiian-born Okinawan-American musician and the director of the Peace for Okinawa Coalition. “It started with the illegal annexation of the Ryukyu Islands.”

After Japan annexed the Ryukyus, a brief hands-off period followed. According to McNally, “The Japanese government [knew] it was going to be very traumatic for [Ryukyuans] to have to assimilate.” But by the time Yonaha-Tursi was growing up, forcible assimilation had long been the norm.

“If we spoke our Okinawan dialects,” Yonaha-Tursi wrote recently, “we were punished, humiliated by having a big wooden tag around our necks. The tag was indicating that we broke the school regulations.… In our textbooks, there was nothing printed about the history of the Ryukyu.”

Oyakawa agreed. “We don’t have a chance to learn our history in the education system,” she said. “The textbook and everything comes from Tokyo, and there’s really little information about Okinawa. Maybe the Battle of Okinawa but nothing of annexation.”

“It was jarring for me when I went back last year,” said Alexyss McClellan, a graduate student in East Asian and Pacific history at the University of California, Santa Cruz, whose mother was born and raised in Okinawa. “People were like, ‘Oh, we don’t even get to learn our own history.’ It’s mind-boggling—academic colonization.”

Oyakawa, McClellan, and three other members of the Okinawan diaspora were in New York for the April 2019 UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, where they publicized demands for recognition as an indigenous people, for Ryukyuan language preservation efforts, for the return of Ryukyuan human remains held by mainland universities, and for an end to the US military presence in Okinawa.

“A first step could be being recognized as an indigenous people,” Oyakawa said, “so we can talk about language and land rights.” Currently, the Japanese government does not consider the Ryukyuan people an indigenous group or even an ethnic minority. Japan legally recognized an indigenous people in its territory for the first time in February, when the government approved the designation of the Ainu people of Hokkaido—previously recognized as the country’s first ethnic minority—as indigenous.

“As an anthropologist, I see that the Okinawan situation and characteristics fit perfectly into the category of an indigenous people in the context of the UN,” Yoshikawa said. “But at the same time, the word ‘indigenous’ is taken by many Okinawans themselves as a negative term.… Some would say they prefer to be treated as Japanese.”

Oyakawa and McClellan recognize that indigenous rights are a complex and at times controversial issue, a difficulty compounded by Okinawa’s tangled history. Allegiance to Japan surged after the reversion of Okinawa to Japanese jurisdiction in 1972, because US control had allowed American Marines and naval officers stationed there to act with impunity—harassing, raping, and even murdering Okinawan civilians with no consequences.

“They would just hit somebody, and when they drove back to the base, through the gates, it was the same as going back to the USA,” Yonaha-Tursi said. “It’s so frustrating. You rape and kill or run over somebody and just go back?”

Though there is greater accountability now, such episodes have not ended. On April 13, for example, a Navy corpsman with a known history of domestic violence and sexual assault stabbed his local-resident girlfriend to death, then killed himself. The painful memories of US military abuses have inspired a wave of activism, especially by the elder generation, which experienced the worst of it. Now, Okinawan senior citizens engage in routine civil disobedience to show their disapproval of the foreign military presence.

“On a daily basis, the people doing sit-ins and trying to blockade the construction trucks are older people,” Yoshikawa said. “They usually end up being carried away by Japanese riot police.”

Yoshikawa lives in Nago, so he’s on the front lines of the fight over construction of the base at Henoko. “Maybe if you live in the US, it’s hard to imagine,” he said, “but living on a small island like Okinawa, the physical reality is there. We have a beautiful environment, but in the same area, we also have military bases. Environmental protection is part of the peace movement. If you want to create a peaceful world, you have to protect the environment.”

In the shallow waters of Henoko-Oura Bay, nearly 1,500 acres of seagrasses sway with the tides, offering the remaining dugongs a feeding ground. In its brief this March, the DOD asserted that the landfill will bury an insignificant 13 percent of that seagrass, which grows along only 10 percent of Okinawa’s coastline. But in the Pentagon’s view, it doesn’t matter anyway, because the department claims no legal responsibility for protecting the dugongs’ natural habitat.

To comply with an earlier decision in the lawsuit, the DOD commissioned its own review of the dugong population and presented it in 2014—but without any of its own scientific findings. The DOD’s 2019 brief explained that a biologist named Thomas Jefferson “comprehensively reviewed available literature” to assess the dugong population and the project’s potential impact. In light of the Jefferson report, the DOD wrote that the Japanese government’s dugong population surveys “fell short of ‘currently accepted’ methods for determining overall populations” but maintained that “this acknowledged data gap—and DOD’s related inability to make an overall finding on population numbers and viability—does not render Japan’s survey data, which cover years of dugong sightings, insufficient for all purposes.” In other words, although the DOD knew Japan’s environmental impact assessment was neither conclusive nor reliable, it offered no better alternative. While the assessment claims “no adverse effects” on the dugongs, the Nature Conservation Society of Japan declared in 2014 that it had discovered 150 new feeding trails for the dugongs in the affected area.

The four NGOs and three individuals are suing the DOD under the National Historic Preservation Act, the only case in which the US law has been levied internationally or on behalf of an animal. It may sound strange, but the grounds are simple: “In 1954, the Government of the Ryukyu Islands (then under US jurisdiction) adopted a law for cultural properties…. The Ryukyu Government designated the dugong a ‘natural monument’ in 1955,” the DOD stated in its brief. The dugong is one of at least 14 species under such designation in Japan. The DOD seems to scorn the classification, arguing that the dugong does not qualify as a “property” to be preserved, so “DOD had no duty—under NHPA Section 402—to assess the impacts of the Futenma Replacement Facility on the Okinawa population of dugongs.”

The DOD’s brief framed the plaintiffs’ suit as far-fetched, but the department already halted construction once. In 2008, the US District Court for Northern California ordered the DOD to comply with the NHPA by assessing the impact of the construction on the dugongs. In April 2014 the DOD submitted the Jefferson report and related findings, stating that an assessment was completed and no impact was found. Construction started three months later. The plaintiffs filed an appeal, which the court rejected, but in August 2017, the Ninth Circuit Court reversed the lower court’s decision, halting construction for a year. During that time, the suit returned to the district court, and in August 2018, the judge again ruled in the DOD’s favor. After further appeal, the case is back in the Ninth Circuit. Though it commissioned a scholarly review of the dugong’s cultural significance, the DOD admitted to “not consulting directly with local Okinawans or otherwise proceeding in accordance with regulations under NHPA Section 106.”

The dugong is just one—albeit one critically endangered—creature being threatened, and likewise, the lawsuit is just one private effort to halt the base construction. Henoko-Oura Bay also contains coral, which environmental scientists think is worth preserving. Japan’s Defense Ministry stated that it would transplant any coral colony threatened by the base construction if it exceeded a meter in length but claimed that in Henoko-Oura Bay, “no single colony larger than 1 meter was identified.” But according to Tokyo-based consultant Ecoh Corp., in a report submitted directly to the ministry, the base of one of the bay’s coral colonies measures 1.6 meters, and another measures 2.9 meters. The government maintains that there’s a break between the living coral cells, meaning that the corals do not count as continuous organisms, while local biologists and geographers note that those corals each share an exoskeleton and “coral is normally deemed as belonging to a single colony if the same external skeleton is shared.”

Beyond that, freedom-of-information requests filed by local residents revealed that the seafloor in Oura Bay is as “soft as mayonnaise,” according to a March 2016 report commissioned by the Defense Ministry. Accounting for about 60 percent of the area designated for construction, the fragile seafloor puts any landfill placed on top of it at risk of sinking back into the earth. The ministry kept its analysis of this obstacle quiet until it was obligated to disclose the report in July 2018, having likely anticipated that increased scrutiny would follow the revelations.

“The ministry has confirmed that the problem of the soft seabed can be overcome through an existing construction method, which has been routinely used, and, thus, the landfill project will proceed in a stable manner,” Defense Minister Takeshi Iwaya told The Asahi Shimbun in May. The ministry plans to use the sand compaction pile method, which will involve driving an estimated 76,000 packed sand pillars into the seabed. While Japan used the same strategy to stabilize coastal seafloor in the past, the government’s work vessels are equipped to drive sand only to 70 meters below sea level, while in Oura Bay, the soft seafloor reaches at least 90 meters under the water’s surface.

“Having been involved with these issues for a long time, on the environmental front, I come to have this opinion,” Yoshikawa said. The “US government and US people should be more angry with the Japanese government for providing such a bogus environmental impact assessment.”

The US DOD and the Okinawa-based US Marines in the Asia-Pacific Region said they were not authorized to comment and suggested contacting other involved governmental organizations. The government of Japan, the Japanese Defense Ministry, and the US Navy did not respond to requests for comment.

“What I want Americans to realize,” said McClellan, “is that this concentration [of bases] would be unacceptable anywhere that we would call home.” The week before she and Oyakawa were in New York, Kajiwara and Yonaha-Tursi were in Washington, DC, meeting with foreign-affairs advisers to congressional leaders and imploring them to call out President Donald Trump for not acknowledging a White House petition launched by the Peace for Okinawa Coalition last December. The petition, which asks the White House to stop the base construction, quickly gathered over 200,000 signatures, more than double the minimum needed to warrant a response. According to Kajiwara, they also proposed a resolution to have Washington recognize Ryukyuans as an indigenous people, because “a US resolution would put a lot of pressure on Japan.”

“The fact that the Japanese government now recognizes the Ainu as an indigenous group but not the Ryukyuans is interesting historically,” McNally said, “because the efforts to assimilate the Ainu actually began before the efforts to assimilate the Ryukyuans.” But, he added, the Ryukyuan and Ainu situations are very different. Despite the long legacy of discrimination, the Japanese “make these claims of ethnic affinity with the Ryukyuans. In my view, this is what Grant found to be most compelling about the Japanese statement.” Even today, most US leaders regard Okinawa as just another part of Japan.

In Okinawa, Oyakawa knows that the fight for justice will be difficult, even on the local front. “We have two colonizers,” she said. Fighting one is hard enough.