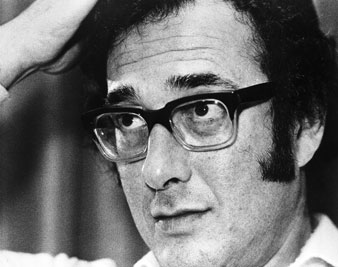

AP ImagesHarold Pinter in New York, 1973

AP ImagesHarold Pinter in New York, 1973

When Harold Pinter died in December, a curtain fell not only on a life of profound artistic achievement but on an era in the English-speaking theater. As Pinter’s life and work were chewed over in obituaries and retrospectives, the disjunctures of the dramatist’s life and work forced themselves into view. A quick temper bubbling over the surface of a deep reservoir of generosity. A messy and devastating midlife crisis and divorce–mined for the stage in Betrayal (1978)–that settled into a deeply devoted second marriage. A playwright celebrated for his audacity and mystery who championed (and directed) the work of Simon Gray–one of England’s most traditional modern playwrights. A devotee of cricket who tirelessly lashed out against US military interventions, from Latin America to Iraq to Kosovo.

Whatever his controversies and contradictions, his legacy as a writer is assured. Pinter is among the few writers one can point to as decisively influential on a genre. (Among fellow Nobelists, one would have to cite Hemingway on fiction, perhaps, or T.S. Eliot on poetry.) There is not a playwright working in English after 1968 or so who doesn’t owe something to the stripping down and refurbishing of theatrical language in Pinter’s early masterworks–a meld of poetry, jargon, slang and strategic silences.

Just as crucial, however, was the way Pinter unhitched English-speaking drama from its most-treasured certainties–clear narrative, defined character. Beckett and Kafka are obvious wellsprings for works such as The Caretaker and The Birthday Party, but Pinter’s innovation was to root existential dilemmas in the quotidian. His early plays are set in dingy flats and seaside resorts, filled with junk and servings of corn flakes for breakfast. When Pinter finally pulls away the threadbare rugs of those same rooms, the audience sees that there is no floor at all–but rather a moral and temporal abyss. There’s shock and awe in this magic act but also palpable surprise and comedy. It’s breathtaking writing–especially when acted well and seen for the first time in performance.

These arrows are in every dramatist’s quiver now. But such an outsized influence as Pinter’s provokes as much resentment as gratitude among playwrights. A shadow so pervasive is, in its way, oppressive–particularly when Pinter’s early plays (and his statements about them) are so slippery, fiercely resistant to ascribing specific meanings and focused resolutely on the search for truth within the process of staging the play.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →The terms of Pinter’s achievement are the central problem of his influence. His knotty and unexpected crises and epiphanies (or are they?) in narrow rooms are an inescapable helix of our theatrical DNA. His plays offer fruitful challenges–and precise choreography–for actors and directors. But they carry the considerable benefit of being much easier to stage in the desiccated economy of today’s theater than the complex Brechtian political epics of, say, Tony Kushner or Howard Brenton. Or even Caryl Churchill’s epic disjunctures of gender and politics in time and space.

As a practical influence, Pinter resembles one of his greatest dramatic creations: Max, the bullying patriarch of The Homecoming. Max enters with a stick from the kitchen, bellowing for the scissors. Pinter’s early vision of a more clipped and less overtly political theater has largely won the day, and decisively so. Even back in 1970, in a speech accepting the German Shakespeare Prize (and printed as a foreboding introduction to the fourth volume of his Complete Works), Pinter’s notion of the rightness of that position is uncompromising: “I am not concerned with making general statements. I am not interested in theater used simply as a means of self-expression on the part of the people engaged in it. I find in so much group theater, under the sweat and assault and noise, nothing but valueless generalizations, naïve and quite unfruitful.”

But any examination of Pinter’s career after the triumph of his most haunted and thorny play–No Man’s Land (1975)–leads inevitably to the knottier question of his political turn in the ’80s. It is a story quite different from the one I have just related–a tale of a writer’s intense artistic and political self-expression, shifting gradually from the specific to the general, and, while rarely naïve, often unfruitful.

Great artists possess political capital–to agitate, if not legislate. And after an early career spent battling critical attempts to pin down the provocative ambiguities of his work, the early plays gradually took on topical meanings as Pinter offered increasingly high-profile statements on politics–and, in particular, American foreign policy. And his later plays, such as One for the Road (1984) and Mountain Language (1988)–both of which deal explicitly with torture–were quite comfortable in their topicality. These plays still possess the power to shock, but they also lack the awe-inducing revelations of mysteries and depths of Pinter’s early work.

Writing in the Observer shortly after Pinter’s death, Nick Cohen spoke eloquently about the numerous contradictions into which the dramatist’s strong indictments of US foreign policy led him–including strong support for Slobodan Milosevic in the 1999 NATO bombing of Kosovo and Serbia. But I am also interested in the effect it had on Pinter’s art. In later years, he increasingly eschewed writing plays in favor of quite didactic and unsuccessful poetry–in which the acid of his invective against the United States corroded his language.

The public forum afforded by the Nobel Prize gave Pinter his most prominent platform to articulate his views on art and politics. Pinter’s brutal onslaught against American foreign policy got the headlines, of course: “The crimes of the United States have been systematic, constant, vicious, remorseless, but very few people have actually talked about them,” he said. Invading Iraq “was a bandit act, an act of blatant state terrorism, demonstrating absolute contempt for the concept of international law.” But look deeper and one sees just how fiercely Pinter was grappling with the questions that his early work had for politics and art. Seeking to clarify the distinctions between truth in art and truth in political art in this address, he only muddies them. Truth in art remained elusive and pursued in the process of writing and staging works. But truth in political art, he argued, can be fixed:

Political theatre presents an entirely different set of problems. Sermonising has to be avoided at all cost. Objectivity is essential. The characters must be allowed to breathe their own air. The author cannot confine and constrict them to satisfy his own taste or disposition or prejudice. He must be prepared to approach them from a variety of angles, from a full and uninhibited range of perspectives, take them by surprise, perhaps, occasionally, but nevertheless give them the freedom to go which way they will. This does not always work. And political satire, of course, adheres to none of these precepts, in fact does precisely the opposite, which is its proper function.

By Pinter’s own definition, much of his later political theater fails. And he elides his poetry by essentially defining it out of the frame. One can only imagine what the 1965 Pinter would have made of the 2005 playwright. But the fact that such a profoundly great and transformative writer grappled so tenaciously with overt engagement with politics and theater is a signal of just how high the bar is for success, and not a warning that it should not be attempted. As I read through much of the coverage of his death and legacy over the past few months, I was struck by this quote from actor Thomas Baptiste, who was directed by Pinter in The Room in 1960, on the Guardian website: “He once told me: ‘Dare to hope, and remember you have the right to fail.'”