IGOR KOPELNITSKY

IGOR KOPELNITSKY

There’s no doubt that news in America is in trouble. Of the 60,000 print journalists employed throughout the nation in 2001, at least 10,000 have lost their jobs, and last year alone newspaper circulation dropped by a precipitous 7 percent. Internet, network and cable news employ a dwindling population of reporters, not nearly enough to cover a country of 300 million people, much less keep up with events around the world. It is no longer safe to assume, as the authors of the Constitution did, that free-flowing news and information will always be available to America’s voters.

It’s time for the public discussion to focus less on what has caused this swiftly escalating crisis–the mass migration of readers to the Internet and the effects of the economic meltdown feature in most explanations–and start talking seriously about solutions. Saving journalism might seem like an entirely new problem, but it’s really just another version of one that Americans have solved many times before: how do we keep a vital public institution safe from the ups and downs of the economy? Private philanthropy and government support are the two best answers we have to this question.

One of the best-known examples of philanthropy’s response to the news crisis is ProPublica (propublica.org), which was founded in 2007 by editor in chief Paul Steiger with retired banking tycoons Herbert and Marion Sandler. The group, which relies mainly on grants from the Sandlers to stay in operation, maintains a staff of thirty-five reporters and editors, who specialize in hard-hitting investigative journalism with a long memory, the kind that cash-strapped commercial media have always been wary of supporting. With stories on Hurricane Katrina and Guantánamo already published in places like the New York Times, the Washington Post and The Nation [see A.C. Thompson, “Katrina’s Hidden Race War,” January 5], the group exemplifies how valuable the nonprofit news sector can be.

The group’s finances and the scope of its operations, however, are a perfect example of why philanthropy can never be the sole answer to America’s news crisis. ProPublica’s annual budget of $10 million is exceptional by philanthropic standards, but it is still less than a single newspaper, Denver’s Rocky Mountain News, was losing per year before its owners shut it down. An army of ProPublicas is needed before America can replace the capacity for good journalism it has already lost.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →That said, the private, not-for-profit news sector is worth paying attention to. Some of the new organizations cropping up might be models for others, if they’re successful. Two representative examples are the Investigative Network (currently a for-profit, with plans to become a hybrid not-for-profit and for-profit entity) and the Under-Told Stories Project. Founded to fill a void in coverage of the multibillion-dollar Texas Statehouse budget, the Investigative Network (pressforthepeople.com) aims to use the revenue it gets from selling subscriptions to niche information streams to fund investigative journalism in the general public interest. The group’s founder, investigative reporter Paul Adrian, hopes that funding will also come from story syndication and philanthropy. Groups with such a diverse mix of support as part of their initial business plans are likely to become more common.

The Under-Told Stories Project (undertoldstories.org) is devoted to increasing public awareness of underreported international topics. The group is funded partly by sale of its stories, most of which end up on public television and radio, and partly by its institutional partner, Saint John’s University in Collegeville, Minnesota. Organizations that get some support from endowed nonmedia institutions might also become more common.

It’s also worth noting that in an environment of diminishing opportunities for young journalists, the Under-Told Stories Project arranges internships. Ensuring that good reporting will be around in the long term is just as important as preserving what we have now, and the private, nonprofit media sector would do well to pursue it more vigorously. (Full disclosure: I am an unpaid adviser to both the Under-Told Stories Project and the Investigative Network.)

Because such fledgling enterprises are potentially so valuable to the health of our media, they should be loudly and publicly encouraged at this stage, even though there will never be enough of them to solve the news crisis on their own. At Harvard’s Hauser Center, I’ve launched a database of nonprofit news efforts (hausercenter.harvard.edu/medialist). Many of the listed organizations are in the early stages of development, and now is the time when publicity and donations can make a decisive difference. If you’re looking for somewhere to donate, or if you know of a group that we haven’t found yet, I urge you to get in touch. But for a nation in the midst of a crippling news crisis, my list is still alarmingly short, and, as a potential replacement for our commercial media, it can never really be long enough.

I would love it if supporting the news were seen as a routine civic obligation–“this month’s city hall coverage adopted by the Elks Club” is easy to imagine–but those days, if they ever come, are likely far in the future, and adopting a stretch of highway is a far cry from building it in the first place.

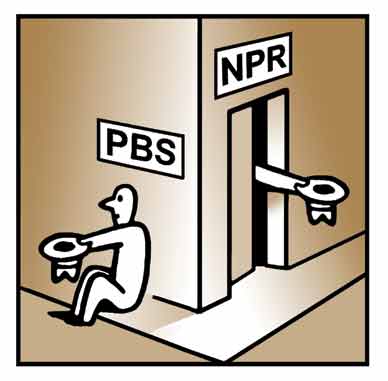

To survive the current crisis, we need bigger, faster solutions. We need to do what other mature democracies have long done: fully fund our public media with tax dollars. Calling in the resources of the central government to bear on any national problem is sure to be obscured by the fog of ideological and partisan distractions permeating the debates about the climate crisis and healthcare. I can already hear the hysterical, clamoring opposition to “socialized media” or “government takeover of the news.”

Better funding for All Things Considered on NPR or NewsHour on PBS will not turn either program into a propaganda outfit for the government. The BBC is not Pravda, and Japan and most of Europe, which have enjoyed extremely well-funded public media for decades, are not a network of totalitarian states. German public television, for example, is amply funded with revenue collected under the aegis of the central government but administered through a decentralized system designed to preserve regional independence. There are numerous democratic nations with public broadcasting systems that are both well funded by their central government and also well shielded from its political influence.

In America, more robust public media won’t weaken or constrain our commercial media. No matter how well funded PBS and NPR become, American cable news will still be free to devote 22 percent of its total coverage to stories like the death and burial of Anna Nicole Smith, as it did in February 2007.

Even though it goes against habits of American governance, and even though the Obama administration and its allies are mired in the slow advance of other ambitious projects, now is the moment to advocate greatly expanding our public media. The rapid corrosion of our commercial news demands that something be done soon, and it is still early in the administration of a popular, progressive president, when sweeping changes are possible.

John Nichols and Robert W. McChesney have correctly deemed efforts to solve the news crisis a national infrastructure project [see “The Death and Life of Great American Newspapers,” April 6]. We don’t leave it up to private nonprofits to maintain our roads and bridges, outfit the Army or provide public transportation. Volunteer militias and private fire departments rightly did not survive the progressive reforms of the nineteenth century. You can still hire a private security firm or travel in a private jet, but the government also assures a basic measure of protection and mobility to every taxpaying citizen. Why shouldn’t it be the same for the news and information whose circulation the founding fathers saw fit to protect in the First Amendment?

Total federal support for American public broadcast media in 2007 was about $480 million. That might seem sufficient or even impressive until you compare it with the BBC, which serves a nation with one-fifth the US population but which received the equivalent of $5.6 billion in government money in 2007. When it comes to public media, the United States is decisively outspent by the governments of most other major democracies. Japan, whose population is less than half the size of the United States’, spent the equivalent of $6.8 billion for public broadcasting in 2007; Germany, with one-third the size, spent about $11 billion; and Canada, a tenth the size, spent $898 million. Even Denmark and Ireland, with populations smaller than New York City, far outspent the United States per capita, with respective budgets equivalent to $673 million and $296 million.

The amount the government now sets aside for public broadcast media is about what it costs the military to occupy Iraq for two and a half days. Taking into account the hundreds of billions lavished on the interim survival of our elite financial institutions, funding our news infrastructure won’t be a hardship. Just a small fraction of the $45 billion–that’s billion with a “b”–Citigroup alone has received since October 2008 would give NPR and PBS all the money they need.

Unlike the benefits that come from bailing out investment banks and insurance conglomerates, a stronger investment in public media would give all citizens a concrete and valuable service. Turn on cable TV news to find out about an event overseas, and you are likely to see a panel of well-coiffed pundits sitting in a studio in New York, Washington or Los Angeles debating what might be happening on the other side of the world. Switch to the same story on the BBC, and you are likely to see a correspondent on the ground where the event is actually taking place. The BBC’s forty-one permanent foreign bureaus are more than twice the number maintained by ABC, CBS, NBC and PBS each. This isn’t a difference of national character; it’s simply a matter of money. For commercial TV, paying pundits is a lot cheaper than doing the real work of reporting. And for public media, chronically small budgets often make extensive original reporting too expensive, even for respected shows like NewsHour.

To discern the real view the American people hold toward public media, it is necessary to pay attention to one fact: voluntary viewer donations provide the biggest chunk of the money that keeps public media in business, and have done so for a very long time. The phrase “supported by viewers like you” is more than a marketing bromide. Except for stalwarts like the Ford and MacArthur foundations and Mutual of America, and in years past Exxon and AT&T, foundation and corporate giving has never provided as much to public television as small individual pledges. But despite its reliability, voluntary public subscription is no way to fund a major public service.

Throughout the two decades I was president of WNET, New York’s PBS station, I spent a lot of time standing in front of cameras asking viewers for money, so I don’t feel ashamed or unqualified to say that even though it has essentially saved the medium and mobilized millions of Americans, the drawn-out, droning pledge drive may finally be reaching a point of diminishing return. After factoring in the salaries of development departments, the costs of direct mail and on-air solicitation, premiums, thank-you letters and the requisite tote bag, a sizable portion of every dollar that comes in to public television is already spent. There is also the less quantifiable cost in viewers who, when faced with a pledge drive, simply change the channel.

For more than fifty years the American people have shown, through their generous donations, that they support the idea and the reality of public media. The government should acknowledge those decades of widespread support by funding NPR and PBS both more extensively and more efficiently.

By increasing direct allocations to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which is responsible for disbursing funding to public TV and radio affiliates across America, the inherent inefficiencies of fundraising via public appeal would be eliminated, and countless hours of airtime would be liberated from pledge drives. It would also mean that Americans would get more in return for the money they already pay to maintain the public media distribution network, which delivers NPR and PBS to 100 percent of the country.

Perhaps most important, pumping more money into our public media infrastructure could fortify the eroding foundation of print journalism, on which the rest of news media depend. News shows on PBS and NPR already routinely call on newspaper and magazine reporters to provide coverage. Expanding this practice could mean jobs for the rapidly growing number of unemployed print journalists, or even the survival of entire newsrooms in cities with closed or downsizing papers.

Once a newspaper or magazine is lost, its particular blend of institutional history, editorial and reporting expertise, and its ties to the community are never fully recoverable. But an expanded public media network, capable of deploying reporters across the nation and around the world, would at least make sure that someone is always available to gather the news, and keep government and business responsible to the public interest.

The costs of letting our journalistic institutions decay aren’t visible like collapsed bridges or tent cities, but they’re just as dire. A thriving news media, which America is in real danger of losing, is the unspoken assumption behind not only the First Amendment but the whole idea of self-government. It shouldn’t seem radical to expect the same government that recognizes the freedom of the press to also ensure the survival of the press.