AP Images

AP Images

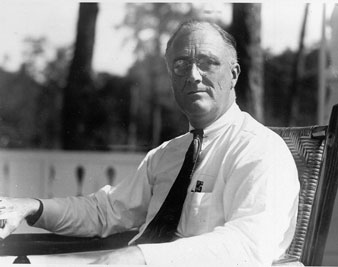

President Roosevelt

As FDR’s administration readies new bills to combat the Depression, Congress is beginning to develop more of a backbone in with the president.

There are signs of a return to normality along the Potomac. Congress is beginning to look more like a legislative body and less like a flock of scared hens. Committees have resumed their functions, and I can testify from personal knowledge that a member of the House this week read a bill all the way through before voting on it. The spokesmen for organized labor and the farmers have injected some discordant notes into the chorus of “Happy Days,” and will inject others before these sizzling sentences see the light. In short, ladies and gentlemen, the honeymoon is over— and a damned good thing for all concerned. By this I do not mean to say that we are about to witness a resumption of the White House-Capitol Hill feud which embittered the latter years of the Hoover Administration. Quite the contrary. Friendly Frank still has his huge majorities in both houses of Congress, and will be able to get from them anything within reason. But it must be within reason, or thereabout— unless, as the vulgar have it, I have misinterpreted my onions. That this turn of events is distasteful to the President is by no means certain; on the contrary, there is credible evidence that he welcomes it. Some things happened during the first two weeks of his Administration which may have taught him that dictatorship has its perils. For example, it is not pleasant to think what might have happened had the Senate emulated the House by passing the emergency bank bill without reading it. No less than thirty-five amendments were adopted for the simple purpose of clarifying its meaning. The President cannot do everything, and this is no time for Congress to abdicate. Its original inclination to do so was largely a reaction to the ignorant and intemperate abuse of editors—who, it appears, have not yet heard what happens to editors under dictatorships.

The first of the bills governing the sale of securities (others will follow) indicates that this Administration does not intend to temporize with the gentry who peddle stocks and bonds in this country. Its provisions are notably more drastic than any heretofore proposed in Congress, and I am informed that succeeding ones will follow the same pattern and disclose the same temper. The blue-sky racket, which reached the zenith of its opulence in the Coolidge-Mellon-Hoover era, is doomed. That it could ever have reached such proportions, and that those who grew rich out of it could have been mentioned as “leaders,” and interviewed and photographed for the newspapers, is but another proof that Americans are the greatest aggregation of suckers ever assembled under one flag. It was only a year ago that Charles E. Mitchell, Otto H. Kahn, Thomas W. Lamont, and the rest were talking down their noses to Hiram Johnson across the table of the Senate Finance Committee, haughtily repudiating the very suggestion that their institutions had done anything improper, and actually proceeding to lecture Congress on its own delinquencies, while the financial writers of the New York papers fawned and scribbled columns of reverential drool. Well, it is satisfying to reflect that if the present bill had been a law during the years when these gentlemen were practicing their art and mystery as it was practiced, several of them would now be occupied with manual tasks behind the walls of Leavenworth or Atlanta. It may not be too late yet. Meanwhile, it develops that not even the Established Church, that is, J. P. Morgan and Company, is to escape the Senate investigation. What is the country coming to? Perhaps to its senses. Incidentally, I cannot leave this subject without remarking on the circumstance that a very large percentage of the Latin American bonds which are now in default, and almost worthless, were issued under dictatorships. Compare their value with that of bonds which have been issued by the democratic governments of the world.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

On the greatest problem confronting it— unemployment— the Administration has made a start, but only a start. Passage of the La Follette-Costigan-Wagner bill, appropriating $500,000,000 for direct relief grants to the States, marks the triumph of a principle for which La Follette and Costigan fought unceasingly but vainly— and at times, it seemed, hopelessly— throughout the last two years. For accepting it and thus insuring its acceptance by Congress, Roosevelt deserves great credit. Its passage in the Senate occasioned some heartburnings. It was difficult to repress a smile when such Southern Democrats as good old Joe Robinson and good old Pat Harrison battled manfully for the inauguration of a policy against which they had battled just as manfully in the past. But in heaven the repentant sinner is thrice welcome, and Robinson in these days might easily be taken for a Progressive. The excellent bill of Senator Black, of Alabama, designed to establish the thirty-hour week in industry, has been favorably reported to the Senate, although its future is not insured.

The rest of the picture, where unemployment relief is concerned, is far less reassuring. At this moment the Administration is toying with two railroad bills, one the so-called Prince plan and the other drafted by a committee headed, incredibly enough, by Joseph B. Eastman of the Interstate Commerce Commission. It is reliably stated that the Prince plan would result in the discharge of 350,000 railroad employees, and that the other would abolish the jobs of about 80,000. If that is any way to relieve unemployment, I’m Herbert Hoover. The situation has produced one good effect: it has virtually forced the railway labor unions to come out for government ownership of the roads. Moreover, although most economists seem to be agreed that a vast public-works program is the only remaining hope of “priming the pump” for economic recovery, the Administration hesitates painfully. The President is confronted with divided counsels, and thus far seems unable to make up his own mind. Liberal members of the Cabinet and Progressive Senators are urging the step; conservative Cabinet members and Budget Director Douglas (who seems obsessed with the notion of being a little Calvin Coolidge) warn against “unbalancing the budget”— God save the mark— as if it had not been out of balance for years. A whisper is current here that New York bankers, being opposed to such a program of public works, would refuse to purchase the bonds which would be necessary to finance it. It is even said they may not buy the securities by which the relief grants are to be financed. I think I can tell my dear friends in Wall Street what will happen if they try any such monkey business. They will witness a bond-selling campaign of the kind conducted during the late war, and they will see about ten million of us rushing up to the counter to sock every spare nickel we own into the new bonds. As a matter of fact, it probably would be an excellent thing for the government to get out of the habit of turning to the bankers when it needs money.Why should our Uncle Samuel be at the mercy of the loan sharks when he has so many relatives willing to stake him?