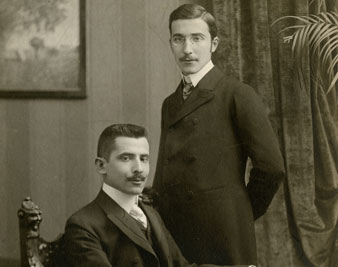

Daniel A. Reed Library at SUNY FredoniaStefan Zweig stands next to his brother Alfred. Vienna, c. 1900.

Daniel A. Reed Library at SUNY FredoniaStefan Zweig stands next to his brother Alfred. Vienna, c. 1900.

Of all the names that ring out from the annals of Viennese cafe society, that storied model for later bohemias, none is more elegiac than Stefan Zweig’s. Hitler destroyed that world, but the Great War had already rung the curtain on its golden age. The greatest names and greatest achievements belong to the three decades surrounding the turn of the century: Mahler, Schnitzler, Klimt, Schiele, Freud. After the war, after the Austro-Hungarian Empire, whose tolerance and multinationalism made Vienna’s cosmopolitan ferment possible, the mood is all of loss, whether nostalgic or disillusioned, Joseph Roth or Robert Musil. But if Roth and Musil come late, Zweig comes last. He wasn’t the youngest or the last to die, but he believed longest in the pan-European culture Vienna represented, and his career embodied the passing of that ideal. Zweig, the most popular author of his day, knew everyone who mattered in European culture, and he seems to have read every thing that mattered. His outpouring of biographical studies–books and essays not only on Mahler, Schnitzler, Roth and Freud but also on Erasmus and Montaigne, Goethe and Nietsche, Dickens and Dostoyevsky, and many, many others–can be understood as a mission, impelled by a growing sense of doom, to preserve European civilization and the humanistic values for which it stood. But though he escaped the camps, he couldn’t escape the sense that everything he cared about was being exterminated. His death in 1942, in a Brazilian backwater, was a suicide.

Zweig’s fiction is also marked by the two catastrophes he witnessed, especially the first. His best-known tale, “Chess Story,” completed, like his memoir The World of Yesterday, on the eve of his death, registers the Nazi hostility to the life of the mind. But two previous stories–he wrote about twenty in all–allegorize the earlier loss. In “Buchmendel” (“Mendel the Bookman,” as it might be rendered), the Great War destroys a living repository of bibliographic knowledge who dared to ignore the political barriers–irrelevant to his universe of culture–the conflict has created. In “The Invisible Collection,” a wife and daughter sell off a connoisseur’s unparalleled assemblage of engravings to stave off poverty during the postwar hyperinflation. The collector is blind by then, and still lovingly caresses the blank pages his family has slipped into his portfolios to conceal the loss. The image is immeasurably poignant, but it is also double-edged: European culture has been erased by history, yet it is still alive in the minds of those who cherish it.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

But nowhere else in his fiction does Zweig confront the legacy of the Great War with as deep a social reach or as detailed a human sympathy as he does in The Post-Office Girl. Zweig completed only one novel, Beware of Pity; The Post-Office Girl was found among his literary remains and published in Germany (as Rausch der Verwandlung, “The Intoxication of Transformation”) only in 1982. Its appearance in English caps a recent spate of republication. Since 2002, Pushkin Press has issued six volumes of fiction, while New York Review Books has published three, all nine of them in attractive editions and many in new, competent translations. Other presses have contributed fresh versions of The World of Yesterday, Marie Antoinette, Zweig’s most popular biography, and another volume of short stories. We have three recent translations of “Chess Story” and two editions of Beware of Pity from which to choose, as well as new versions of some fourteen other tales.

Still, posthumous publication is a dicey business. There’s been more and more of it lately, for obvious reasons. Venerated authors represent established “brands” guaranteed to move product, one of the few sure bets in an increasingly anxious business. Artistic integrity and the writer’s wishes don’t enter into it. Ernest Hemingway and Elizabeth Bishop, celebrated perfectionists both, are only two of the authors lately subjected to the publication of material they had chosen to suppress. New York Review Books, established in 1999 to revive neglected classics, is presumably acting on nobler motives here, but there is reason to question its judgment nevertheless. Zweig nibbled at The Post-Office Girl for years. The NYRB press material claims that the novel was found completed after its author’s death, “awaiting only minor revisions,” but the afterword to the German edition describes a manuscript in considerable disarray. Given that Zweig chose his own time of death, and given that he had just finalized two other works and dispatched them to his publishers, it seems clear that he never managed to hammer the novel into a shape that satisfied him. NYRB, which seems to have gotten a little carried away here with its project of reclamation, should at least have provided the volume with an introduction (as it did in the case of its other Zweig reissues) airing these questions fully and candidly.

Nevertheless, we are lucky to have the book, not only for its devastating picture of postwar Austrian life but also because it represents so radical a departure from Zweig’s other fiction as to signal the existence of a hitherto unsuspected literary personality. No wonder he struggled with it for so long; he was listening to a new voice, and he may never have fully figured out what it wanted to say. The typical Zweig story is a tale of monomaniacal passion set loose amid the veiled, upholstered civility of the Austrian bourgeoisie, the class into which Zweig was born. A wife in a corseted marriage, an army officer stunted by the regimented routines of duty, an aesthete numbed by his meaningless rounds of pleasure–through a chance encounter or a moment of moral daring, each is precipitated into a state of almost demonic possession by guilt or greed or desire. Zweig, whose obsession seems to have been obsession itself–he speaks in “Buchmendel” of “the enigmatic fact that supreme achievement and outstanding capacity are only rendered possible by mental concentration, by a sublime monomania that verges on lunacy”–was alive to both the life-affirming and the self-destructive potentialities of the situation. Repression, released at last, careens past exhilaration toward derangement. Zweig’s newly awakened protagonists finally notice the world and feel its urgency pressing in on them for the first time, but their souls don’t know what to do with so much feeling.

There are whiffs of Dostoyevsky here, and of the nineteenth-century Decadents, and even occasionally of Sacher-Masoch, another Viennese–Zweig was largely uninterested in postwar Modernism, and he can feel like a throwback to the fin de siècle–but the major influence, of course, is Freud. Zweig, who delivered an oration at his friend’s funeral, saw himself as a kind of Freud of fiction, a fellow spelunker in the caverns of the heart. His prose attends not only to the moment-by-moment fluctuations of his characters’ inner turmoil but also to the symptomatology manifested on their bodies: the tremor of a gambler’s hands, the shifts of an adulteress’s gaze. His characteristic method is also Freudian. Nearly all his tales feature a frame narrator, someone to whom the protagonist confesses her secrets. The encounter typically takes place at a continental resort or hotel, one of those cosmopolitan spaces of luxury and mystery. Storytelling bridges the distance between strangers–culture doing its unifying work–but it also marks the distance between the narrator and the volatile emotional material he handles. The telling of the tale becomes a kind of resocializing device, replacing the containing structures that have broken down within the tale, and the narrator becomes a kind of analyst or, indeed, a connoisseur. In “Moonbeam Alley,” the narrator clearly speaks for Zweig when he evokes “the delightful sensation of an experience made deepest and most genuine because one is not personally involved,” a sensation, he says, that “is one of the well-springs of my inmost being.”

By renouncing the pleasures of vicarious feeling, The Post-Office Girl achieves an immediacy otherwise unequaled in Zweig’s fiction. No frame narrator screens us from the title character, 28-year-old Christine Hoflehner, postal clerk in the sleepy Austrian village of Klein-Reifling. The year is 1926. Christine shares a dank attic with her rheumatic mother. Her youth has been stolen by the war, along with her father, her brother and her laugh. But into the gloom of her days a sudden light breaks–a telegram from her aunt Claire, gone to America years before and now come back a rich lady. Claire invites her niece to join her on holiday in Switzerland. With a limpid and sensuous directness, Zweig renders the intoxication of the transformations that follow: the provincial girl’s “first reckless gulp” of “glass-sharp” alpine air as she throws open the window of her train, her newly awakened shame as she creeps into the grand hotel clutching her straw suitcase, the greedy flare of her nostrils as her aunt inducts her into the world of finery. This is Christine in the beauty salon:

Now fragrance from a shiny bottle streams over her hair, a razor blade tickles her gently and delicately, her head feels suddenly strangely light and the skin of her neck cool and bare…. She’s aware of it all and, in her pleasant detached stupor, unaware of it too: drugged by the humid, fragrance-laden air, she hardly knows if all this is happening to her or to some other, brand-new self.

The notation is swift and simple. When Zweig’s characters tell their own stories, by contrast, the prose can be overwrought, the effect distractingly self-conscious. Here, for example, is the protagonist of “Fantastic Night” undergoing an analogous awakening:

No, it was not shame seething in my blood with such warmth, not indignation or self-disgust–it was joy, intoxicated joy blazing up in me, sparkling with bright, darting, exuberant flames, for I felt that in those moments I had been truly alive for the first time in many years, that my feelings had only been numb and were not yet dead, that somewhere under the arid surface of my indifference the hot springs of passion still mysteriously flowed, and now, touched by the magic wand of chance, had leaped high, reaching my heart.

In place of such labored figures, Zweig marks Christine’s discovery of the life of pleasure, and the unfolding of her newfound self, with fresh, unfussy imagery: a carnation in a vase is like “a colorful salute from a crystal trumpet”; her first sip of wine goes down “like sweet chilled cream”; the silk dresses her aunt picks out “glisten like dragonflies,” their “yielding new fabric” a “warm, delicate froth on her skin.” Christine’s body is awakening for the first time, and the language transmits the sensuality of that experience.

Zweig was never shy about making use of traditional narrative models. The main archetype here is Cinderella, of course, but Sleeping Beauty enters in, as well. Christine isn’t just poor and overworked; she’s been in a state of suspended animation ever since the war interrupted her womanhood just as it was getting started. What her fairy-godmother aunt makes possible with a wave of her magic purse is nothing less than Christine’s repossession of her femininity. Within the space of a few days, even a few hours, she learns what it feels like to be beautiful, to be fashionable, to be noticed. She falls in love with the image in her mirror and gives herself a new, more elegant name. She runs in the mountains and shakes the dew from her hair. She dances to hot music, makes out in the back seat of a roadster and stays up late gossiping with her girlfriends. She isn’t particularly admirable at this point, neglecting her aunt in favor of the fast new set she’s fallen in with, forgetting to write to her ailing mother, adjusting all too easily to a life where other people do the work. As usual, Zweig doesn’t make our moral allegiances easy. But the story’s direction seems clear. Christine is pursued by two men, a handsome young German engineer–he’s the fellow with the roadster–and a protective old English general: sexy Herr Wrong and courtly Lord Right, a love triangle in which she seems certain to get caught on the wrong side.

And then, with the suddenness of someone pulling the plug on a carousel, Zweig brings the whole thing to a halt. Christine’s friends discover that she’s not the young lady she’s been pretending to be, and Aunt “Claire (formerly Klara)” fears for the discovery of her own long-buried secrets. After scarcely more than a week, Christine and her straw suitcase are sent packing back to Klein-Reifling. Midnight has struck for Cinderella, but there will be no glass slipper and no prince. If anything, Christine’s life is even worse than it was before, because now she knows what she’s been missing. Suspended animation is one thing, but this feels like death, the death of the new, true self who had only just begun to stir. The village becomes intolerable:

The women seemed ridiculous to her in their full gingham skirts, with their greasy hair piled on top of their heads and their plump hands covered with rings, the heavy-breathing, potbellied men unbearable, and, most repellent of all, the boys with their pomaded hair and citified airs.

The sweet little schoolmaster who had courted her shyly before her departure is now “intolerably lower middle class”–a term that would never have occurred to her before. In moving the novel away from the grand hotel toward a more complex counterpointing of social spheres, Zweig opens his fiction for the first time to a world of economic realities that lies below his own experience. The wonder is that he succeeds in imagining those realities with such an intimate specificity.

The expansion of Christine’s consciousness, and the novel’s, is only just beginning. Visiting her sister Nelly’s family on a trip to Vienna, she meets Ferdinand, her brother-in-law Franz’s comrade from the war. Whatever reasons Christine has for resentment, Ferdinand has many times over, and whatever awareness has started to break in on her, he has articulated long ago. Ferdinand spent years in a Siberian prison camp, only to return to a country that no longer had any use for him. His dreams of becoming an architect have been dashed by poverty, his chances for even decent employment wrecked by injury. His family wealth evaporated in the hyperinflation. He has beaten on the doors of ministries, climbed the stairs of government agencies, and has nothing to show for his talent and drive but the sense of a wasted life.

When Ferdinand’s bitterness comes pouring out in a torrent of savage eloquence, Christine recognizes a kindred spirit. Unlike the priggish Nelly or the paunchy Franz, here is someone who refuses to accept the radically diminished expectations imposed by the war. A potent system of imagery links the two. Christine feels “like a severed finger still warm yet without feeling or strength.” A finger is exactly what Ferdinand has injured, but, he says, “you wouldn’t believe what a dead finger does to a living hand.” But that is not his only disability. “Once they’ve cut six years out of your body…you’re always a kind of cripple.” This is what it feels like to be dispossessed, to be marginalized, to be cheated out of the life you could have had and the person you could have been: it feels like you’ve been cut in half. Zweig is again tracing the commerce of body and soul, and the sensuousness of his earlier, happier descriptions pays off double here, because he renders the life of deprivation with equal immediacy. “The smell is suffocating,” Christine thinks of her attic room, “the smell of stale cigarette smoke, bad food, wet clothes, the smell of the old woman’s dread and worry and wheezing, the awful smell of poverty.” “Poverty stinks,” Ferdinand echoes her, “stinks like a ground-floor room off an air-shaft, or clothes that need changing. You smell it yourself, as though you were made of sewage.” Poverty isn’t just doing without; it is also shame and impotence and self-disgust. War isn’t just bullets; it is also what happens afterward.

All of this represents an immeasurable advance over Zweig’s other fiction. Instead of a single emotion intensively examined within a narrow social frame–a fair description even, as its title suggests, of Beware of Pity, though that work is considerably longer than The Post-Office Girl–Zweig gives us fully rounded lives rooted in a broad historical context. This, he is telling us, is what the war has done to people. This is what history has made of their bodies. This is the fate of a whole generation. The question of historical luck, and thus of the possibility of alternative lives or selves, is everywhere at issue. Franz made it home right after the war; Ferdinand got stuck in Siberia for an extra two years. Klara was sent off to America; her sister Maria, Christine’s mother, spent the war working in a damp hospital basement. The postwar generation of girls is bold and shameless, but everywhere Christine looks she sees women like her, who have missed their chance at life.

The affair she begins with Ferdinand, two souls clinging together for friendship more than anything else, is no less immune than they to the withering circumstances of their lives. The couple contemplate suicide, then conceive a plan that will enable them to escape a different way. And that’s where the novel breaks off. Did Zweig intend to end it there? He might have. The narrative terminates at the conclusion of a scene, and on a thematically significant word. But it would have taken an even greater departure from his normal practice than any other the novel exhibits for Zweig to have suspended the story on such a radically Modernist note of openness, before even a climax, let alone a resolution. Zweig’s own death involved a suicide pact–he was found lying hand-in-hand with his second wife–and perhaps he simply never succeeded in imagining what a different ending could have looked like. On the other hand, by 1942, Christine and Ferdinand’s future would have been all too clear. The rage, the feelings of betrayal, the sense of wasted talent: the Great War’s toxic human residue, expressed so starkly in Ferdinand’s long denunciatory speeches, would fuel the politics of the 1930s. A million Ferdinands, roused by such tirades, would put on shirts of brown or black and dance the death march of Old Europe.