“On Monday, my house disappeared.”

So begins Brian Fies’s new graphic memoir, A Fire Story, a unique on-the-ground portrayal of the aftermath of the Tubbs Fire, which blazed through California’s Napa and Sonoma counties in October of 2017, killing 22 people and decimating 5,636 structures across 36,807 acres. Fies returned to his house six hours after evacuating in the middle of the night. It had burned to the ground. In response, the cartoonist immediately started documenting the charred landscape, processing the wreckage the best way he knew how: through comics. Less than a week after the fire destroyed his home, Fies posted his first piece about the experience on his blog. His webcomics went viral, and an animated version of the cartoons, made for San Francisco’s local PBS station in 2018, garnered an Emmy Award.

A Fire Story combines Fies’s webcomics into a single narrative, following the cartoonist and his wife, Karen, a local social-services administrator, as they evacuate to their adult daughters’ apartment, survey the damage to their home, deal with the bureaucracy of insurance companies, and struggle to start their lives anew. Apart from his own personal fire story, Fies also tells those of a few of his neighbors, using large blocks of texts to describe each person’s experiences—more or less in their own words.

This isn’t the first time Fies has created a graphic memoir from a tragic personal event. His first foray into graphic literature, 2006’s Mom’s Cancer, describes Fies’s experiences coping with his mother’s lung-cancer diagnosis and treatment. (Like A Fire Story, Mom’s Cancer started out as a webcomic.) With an academic and professional background in science and journalism, Fies has his own vision of what a good graphic novel should look like. “I’ve done a lot of different things that try to combine my interests in art, writing, and science,” he says. “I’m very happy doing graphic novels, so I finally figured out how to do it all at the same time.”

I interviewed Fies about his new work. Below is a transcription of our conversation. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

—Elena Goukassian

Elena Goukassian: How are you and your wife doing?

Brian Fies: My wife and I are doing all right. We actually rebuilt our house in the same spot, and we moved in at the end of March. Most of our neighbors are coming back, too. It’s very neat. I mean, we like our neighbors, and if anything, this whole disaster has brought us quite a bit closer together. I really expect that when, a year from now, we’re all in our rebuilt houses and we get together and have barbecues, that we’ll just sit around and tell stories and be burn buddies, you know? We’ve been through this thing together, and it’s hard to really have those conversations with people who haven’t.

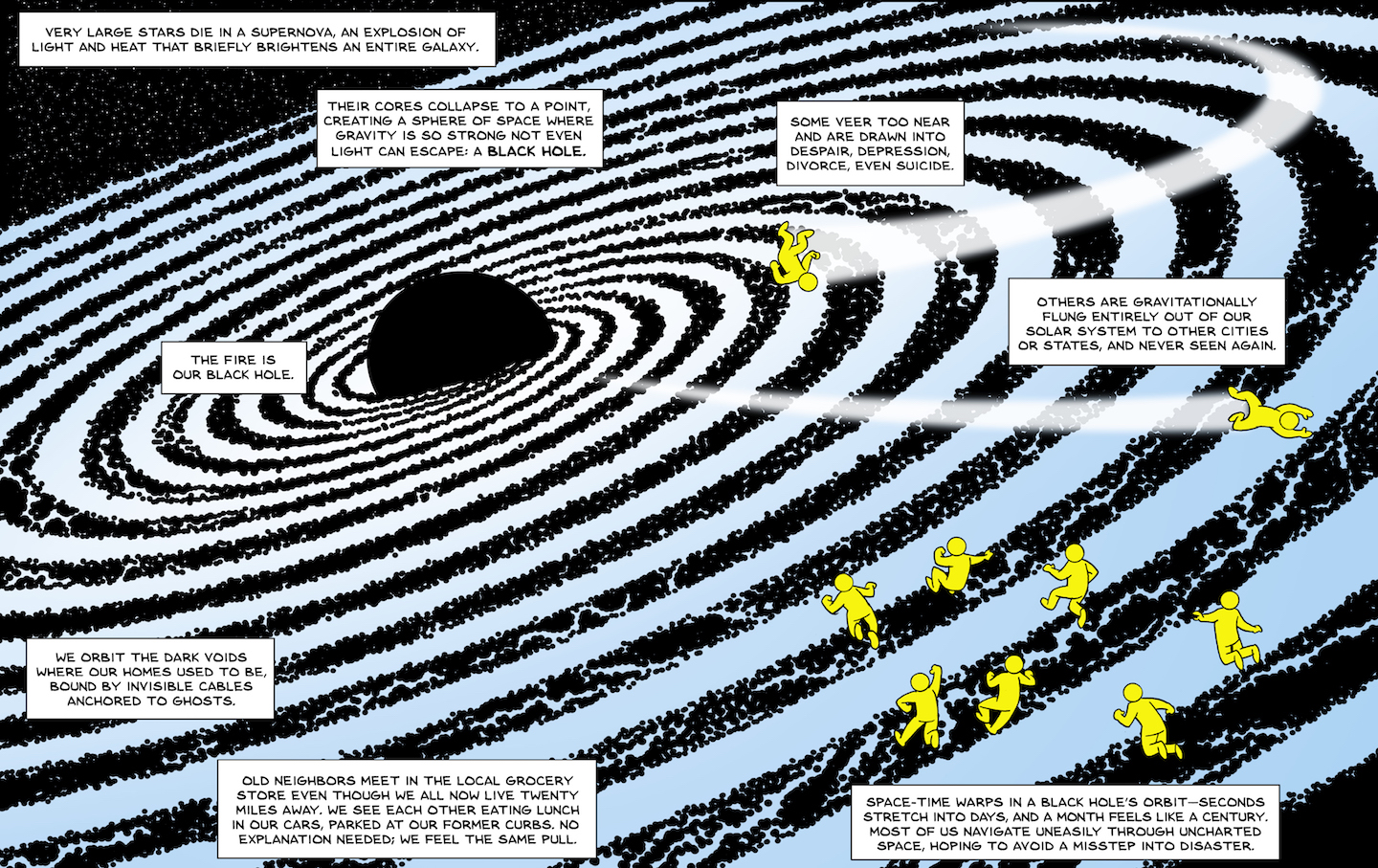

But hardly a week goes by that we don’t bring ourselves up short and think of something we’ll never see again. Or something we don’t remember if we have. Now that it’s been a year and a half, there are a lot of times when we just don’t remember if we have that black-and-white polka-dotted shirt, or that colander. Was it something we had before the fire? Something we bought after the fire? It’s very disorienting sometimes. I don’t think there’s such a thing as closure. I think you just build a new life from that day, and that will always be the dividing line, no matter how old we get or what happens to us, our lives will always be split between before the fire and after the fire.

EG: Your personal story was very important in A Fire Story, but I really liked that you also related some stories from your friends and neighbors.

BF: The sad thing about something like this is you can’t throw a rock without hitting someone with an interesting story. I very much wanted the expanded graphic novel of A Fire Story to be a work of journalism. I wanted to expand it beyond my little bubble of a story and talk about other people’s stories and about the context of geography and climate, socioeconomics. I was very much aware that my experience was a narrow window into this thing. It was bounded by where I lived, how much money I had, my family situation, so I really wanted to go out and find people living different lives. Like Dottie, who it turned out didn’t lose her home in the fire but was still—is still—in dire straits. She is an older woman without a lot of resources, who still doesn’t know how she’s going to get through the day. I talked to a lot of people to feel them out and decided on a few people to interview in depth, because I thought they captured the breadth of the story.

EG: What was it like going back to your neighborhood after the fire?

BF: It looked like an atomic bomb had hit it. I was trying to grapple with the information my eyes were feeding to my brain and it was a very, very weird feeling. I’m standing in front of my house, and I’m seeing it burned down, and even while I’m standing there, I had a little pair of observer’s eyes looking over my own shoulder: “Pay attention, because you need to tell this story.” So I took pictures, I took notes of my surroundings, and I went into reporter mode, and even in this weird, traumatic situation, I started thinking how I was going to turn this into a story.

EG: How did your wife’s job as a civil servant give you a unique viewpoint of the fire?

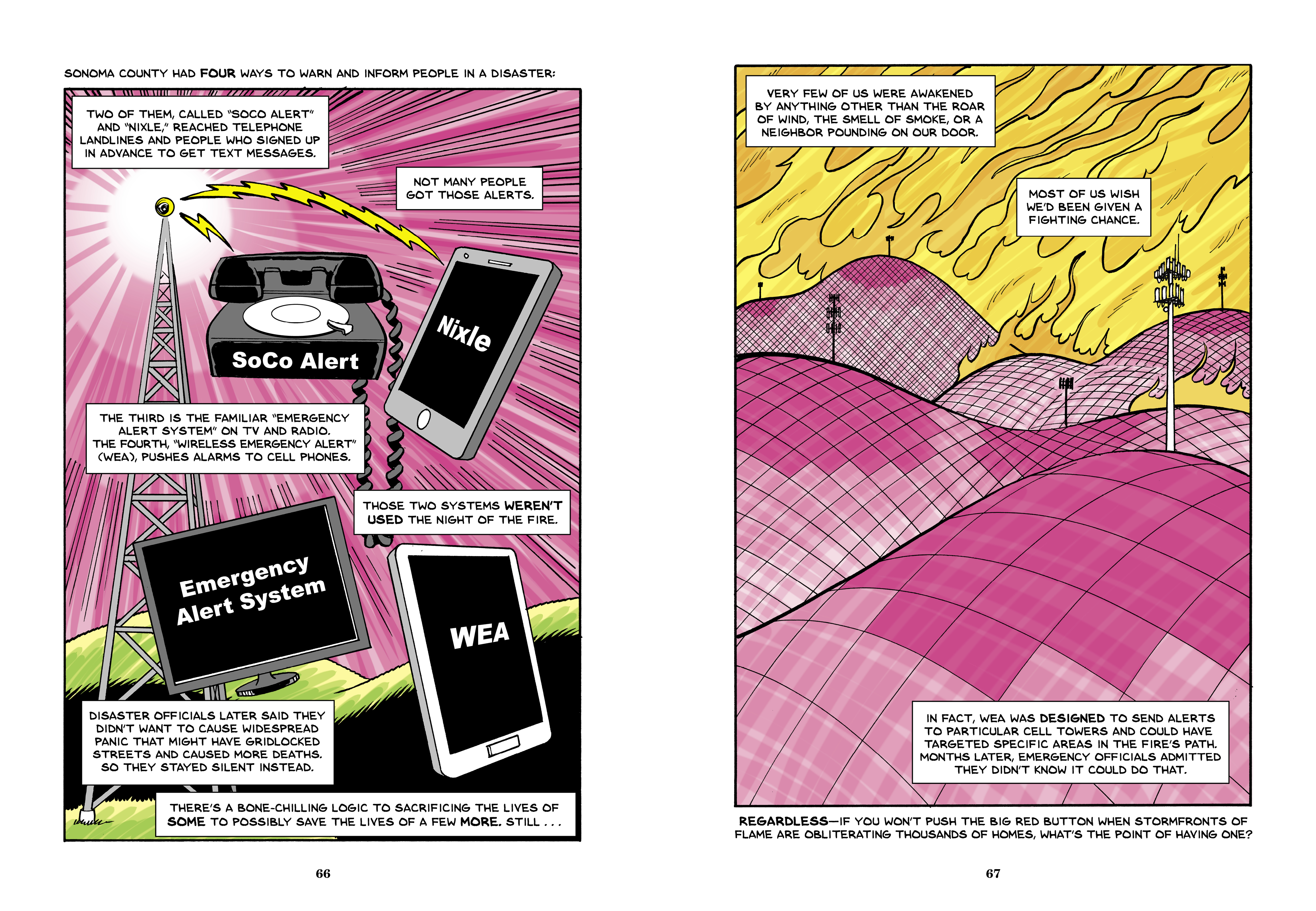

BF: My wife is the director of Sonoma County Human Services, which is basically our social-services department. As I describe in the book, she went right to work that night. Before we knew our house was gone, 20 minutes after we evacuated, she was at work, putting together shelters in high-school gymnasiums, evacuating foster children from a home, and trying to activate phone trees. It was insane, because half her staff didn’t know there’d been a disaster yet, and the other half couldn’t get there because the roads and freeways were jammed and impassable.

It was an interesting perspective, in that I got a sense of how hard she and people like her trying to manage this emergency were working. Nobody had a good idea of how big this fire was, of where it was going, of what had burned and hadn’t burned. It took a good 24 hours before anybody even understood the scope of this disaster. It was just so fast. We went to bed at 10:30 the night before the fire, aware that there was a fire 20 miles away, but we weren’t worried about it. And three hours later it came at 50 miles an hour and burned through our neighborhood.

EG: Do you find making comics cathartic? Is it a way for you to process what’s going on in your life? Or is it more of an impulse?

BF: It’s really interesting you used the word “cathartic.” My wife, Karen, said exactly the same thing to me when I told her I was doing Mom’s Cancer and, later, A Fire Story: “Well, it’ll be good therapy for you.” And, I think that’s true to some extent. The comics give me some illusion of control in a situation in which I have none. I can’t cure cancer, I can’t put out a record-breaking wildfire, but I can control the narrative of what I’m writing and drawing in that little world of the comic.

I think there’s something special about putting it on the page and memorializing it, capturing it in that act, but at the same time, when you do a graphic novel, you’re in that headspace for usually more than a year. You have to wallow in it. I’ve talked to other people who’ve made graphic novels in the health-related fields, and I’m not at all sure it’s healthy. We’re not sure it’s cathartic.

It’s very hard, because I had to talk about the fire long after it was over. I had to remember what it was like to be standing in front of my burned-out house six months after the fact. It may feed the PTSD rather than resolve it, but at the same time, I had to deal with it, understand it, analyze it, and ask myself why I felt that way when I was in that situation. It’s difficult, tricky, and strange. A lot of people have said, “I don’t know how you were able to do that, start making a comic after your house burned down,” and I just don’t think I had any choice. I felt like it was something I had to do.

EG: How do you translate grief and trauma into a relatable comic form?

BF: I try—as clearly as I can, with as little pathos as I can—to explain what happened, and how I felt about it. I don’t want to be a sentimental writer. These situations are so extreme that the pathos is baked into the story, so I don’t have to turn the knob up to 11.

This is what I like about comics and why I work in comics: They are extractions of reality that encourage empathy. Comics are text and graphics down to their essence. They are great at symbolism and metaphors. They don’t just speak the comparison; they can actually illustrate the comparison you’re trying to make with your metaphor. I think our memories are like cartoons, too. We don’t remember a photographic version of an event. We don’t remember all the dialogue carefully recorded. What we remember is our impression of it. We remember the important people who were there, a sketch of the environment, how it made us feel. That’s a cartoon. Comics are naturally attuned to how people remember things. People are primed to fill in the missing detail from a cartoon with details of their own lives, and you put that together and it makes comics an outstanding medium for provoking, invoking empathy. I think this is why many successful examples—like Maus, Fun Home, and Persepolis—are memoirs. When a comic’s really working, when it’s firing on all cylinders, a good comic is like a direct tap from the author’s brain into the reader’s brain.

EG: Do you tailor your drawing style to the stories you tell?

BF: Something I learned in Mom’s Cancer was that when I sat down to write a comic about cancer, my first instinct was to make it very dark, gothic, cross-hatch, and scritchy-scratchy. Gloomy drawings. I can draw like that, but I realized very quickly that I wanted to go the other way. I didn’t want to repel readers; I wanted to draw them in. And so, with Mom’s Cancer I drew in a very clean, light, kind of like a 1950s comic-strip style. I thought of Mom’s Cancer as The Family Circus in hell.

I felt very much the same way with A Fire Story. I wanted it to be accessible. If you grew up on newspaper comics or comic books, my style will feel very familiar to you. And that’s deliberate. If the reader has to stop to figure something out, I’ve failed. I strive for clarity of image, clarity of ideas. My ideal comic would be one line on a perfectly blank piece of paper that perfectly captures what I want it to say. I’ll never achieve that, but that’s my Platonic ideal.

EG: What have the reactions to A Fire Story been like?

BF: I’ve gotten two types of reactions that are very gratifying to me. People who went through the fire tell me I got it right. They tell me that my pictures captured thoughts that they had that they didn’t know how to express. That means the world to me. And the other reaction is people who weren’t here say that, while they saw the disaster on TV, and they saw the footage and the mushroom cloud rising up over the plains of California, my story was the only thing they read that made them understand what it was like to be here, on the ground. I appreciate that very much. That means I did something right.

EG: What are the most common misconceptions that people have about wildfires, the damage they do, how they’re handled—all of that?

BF: I think what people underestimate is the importance of the wind. I describe what hit us as a “napalm tsunami,” and that was because of the wind, a front of hot air moving at 60, 70 miles an hour that drove that fire to consume a football field of terrain every three seconds. The problem wasn’t the fire. The problem was the wind. Fire was burning sideways, and it was skipping terrain that would’ve otherwise been an ideal fire break. It went right over a six-lane highway like it was nothing. And then it flew two miles past that freeway and burned down a neighborhood without burning anything in between. I didn’t know a fire could be this big, hop this fast, move like this. As we evacuated our neighborhood, I was looking at the sky, and we couldn’t actually see any flames, but I could see this glow that looked like a sunrise at 1:30 in the morning, and I could not conceive of how a fire got into our neighborhood. There’s nothing you can do to stop it. I don’t think anything would have mattered—like clearing the underbrush of the forest, constructing our home out of different materials. This thing just burned everything in its path.