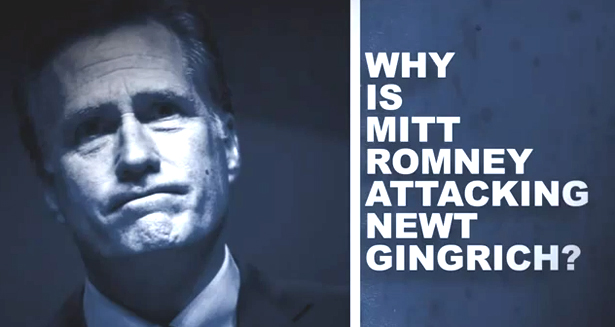

Still from an ad released by Newt Gingrich’s campaign.

We have seen the future of electoral politics flashing across the screens of local TV stations from Iowa to New Hampshire to South Carolina. Despite all the excitement about Facebook and Twitter, the critical election battles of 2012 and for some time to come will be fought in the commercial breaks on local network affiliates. This year, according to a fresh report to investors from Needham and Company’s industry analysts, television stations will reap as much as $5 billion—up from $2.8 billion in 2008—from a money-and-media election complex that plays a definitional role in our political discourse. As Obama campaign adviser David Axelrod says, the cacophony of broadcast commercials remains “the nuclear weapon” of American politics.

We’ve known for some time that the pattern, extent and impact of political advertising would be transformed and supercharged by the Supreme Court’s January 2010 Citizens United ruling. But the changes, even at this early stage of the 2012 campaign, have proven to be more dramatic and unsettling than all but the most fretful analysts had imagined.

Citizens United’s easing of restrictions on corporate and individual spending, especially by organizations not under the control of candidates, has led to the proliferation of “Super PACs.” These shadowy groups do not have to abide by the $2,500 limit on donations to actual campaigns, and they can easily avoid rules for reporting sources of contributions. For instance, Super PACs have established nonprofit arms that are permitted to shield contributors’ identities as long as they spend no more than 50 percent of their money on electoral politics. So the identity of many, possibly most, contributors will never be known to the public, even though they are already playing a decisive role in the 2012 election season. Former White House political czar Karl Rove’s Crossroads complex, for example, operates both a Super PAC and a nonprofit. And Rove’s operation is being replicated almost daily by new political operations aiming their money at presidential, Congressional, state and local elections. “In 2010, it was just training wheels, and those training wheels will come off in 2012,” says Kenneth Goldstein, president of Kantar Media’s Campaign Media Analysis Group. “There will be more, bigger groups spending, and not just on one side but on both sides.”

The 2012 campaign has already confirmed that Super PACs are key players, more powerful in many ways than the campaigns waged by candidates and party committees. But don’t expect commercial media outlets to shed much light on these secretive powers. Newsroom staffs have been cut, political reporting is down and local stations are too busy cashing in on what TV Technology magazine describes as “the political windfall.” The Citizens United ruling and its Super PAC spawn have created a new revenue stream for media companies, and they are not about to turn the spigot off. “Voters are going to be inundated with more campaign advertising than ever,” one investor service wrote in 2011. “While this may fray the already frazzled nerves of the American people, it is great news for media companies.” Indeed, Super PAC ads allow stations to reap revenues from actual campaigns and from parallel “independent” campaigns targeting the same audience with different messages.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Here’s what the next stage of American politics looks like on the screen: WHO, the NBC affiliate in Des Moines, was awash in political advertising the night before the Iowa caucuses. But some ads stood out. One of the most striking was a minute-long commercial featuring amber waves of grain fluttering in the summer breeze, children smiling and a fellow with great hair declaring, “The principles that have made this nation a great and powerful leader of the world have not lost their meaning. They never will.” Then the guy with the great hair announced, “I’m Mitt Romney. I believe in America. And I am running for president of the United States.”

Then came another ad, darker and more threatening, with grainy production values, old black-and-white photos and a blistering assault on the Republican presidential contender who had briefly leapt ahead of Romney in the polling: former House Speaker Newt Gingrich. “Newt has more baggage than the airlines,” the ad warned, before linking Gingrich to “China’s brutal one-child policy,” “taxpayer funding of some abortions,” “ethics violations” and “half-baked and not especially conservative ideals.” Quoting a National Review poke at Gingrich, the ad closed with the line: “He appears unable to transform, or even govern, himself.”

The first commercial is an old-school “closing argument” ad, all optimism and light, along with the usual campaign-season balderdash—the empty banalities of a front-running contender appealing to “principles” and a belief in America. The second represents another archetype: the no-holds-barred takedown of an opposing candidate, which politicians and their consultants traditionally avoid running on the eve of a big vote for fear of muddying their own message and appearing too negative. Romney’s campaign paid for the “amber waves of grain” ad. But who was responsible for the “Newt Gingrich: Too Much Baggage” ad? Restore Our Future, a Super PAC that collected $30 million for the 2012 campaign—more than the combined spending of Lyndon Johnson and Barry Goldwater on the 1964 presidential campaign. And when Gingrich shot to the top of the polls a month before the Iowa caucuses, the group steered $4 million into a TV ad campaign that knocked the former Speaker out of the lead and into a dismal fourth-place finish.

Who finished first in Iowa? And a week later in New Hampshire? The guy with the great hair and all the talk about “principles”—Mitt Romney. He also happened to be the guy who appeared before a dozen potential donors at the organizational meeting for Restore Our Future in July 2011. Romney’s former chief campaign fundraiser moved over to Restore Our Future, as well as his former political director and other aides. Romney’s old partner at Bain Capital helped Restore Our Future get off the ground with a $1 million check. Technically there can be no collaboration between Super PACs and the candidates they are supporting. But Timothy Egan of the New York Times stated the obvious: “This legalism of ‘no coordination’ is a filament-thin G-string. Everyone coordinates.”

Gingrich complained about the presumably unethical and potentially illegal level of coordination between the “principled” Romney campaign and the thuggish Restore Our Future project. When Romney pled innocence and ignorance, Gingrich said: “He’s not truthful about his PAC, which has his staff running it and his millionaire friends donating to it, although in secret. And the PAC itself is not truthful in its ads.” But the griping didn’t get him very far.

* * *

By the time the 2012 race formally began, on January 3, Super PACs had already logged $13.1 million in campaign spending in early caucus and primary states, most of it in Iowa and most of it negative. Romney, whose actual campaign spent only about one-third as much money on ads as did the Super PACs that supported him, emerged as the narrow winner. But he wasn’t the only winner in Iowa or New Hampshire, where a similar scenario played out a week later. Local television stations like WHO in Des Moines and WMUR in Manchester cashed in, big-time, as would stations in later primary states. And station managers in battleground states across the country can hardly wait for the real rush, which will come when the Super PACs that have already been positioned to support the Republican nominee and Democrat Barack Obama spend their money in what is all but certain to be the first multibillion-dollar presidential race in history.

The total number of TV ads for House, Senate and gubernatorial candidates in 2010 was 2,870,000. This was a 250 percent increase over the number of TV ads aired in 2002, when the same mix of federal and state offices was up for grabs. Compared strictly with 2008, the amount spent on TV ads for House races in 2010 was up 54 percent, and the amount spent on Senate-race TV ads was up 71 percent. Even before this year’s Iowa binge, it was clear that 2012 would see a quantum leap in spending from 2008, the greatest increase in American history, and most of this would go to TV ads. As Maribeth Papuga, who oversees local TV and radio purchases for the MediaVest Communications Group, says, “We’re definitely going to see a big bump in spending in 2012.”

It’s not as if Americans haven’t already seen big bumps on what is becoming the permanent campaign trail. Consider how politics has changed in the past four decades. In 1972, a little-known Colorado Democrat, Floyd Haskell, spent $81,000 (roughly $440,000 in 2010 dollars) on television advertising for a campaign that unseated incumbent Republican US Senator Gordon Allott. The figure was dramatic enough to merit note in a New York Times article on Haskell’s upset win. Fast-forward to the 2010 Senate race, when incumbent Colorado Democrat Michael Bennet defeated Republican Ken Buck. The total spent on that campaign in 2010 (the bulk of which went to television ads) topped $40 million, more than $30 million of which was spent by Super PAC–type groups answering only to their donors. In the last month of the election, negative ads ran nearly every minute of every day. The difference in spending, factoring in inflation, approached 100 to 1. The 2010 Colorado Senate race is generally held up by insiders as the bellwether for 2012 and beyond. As Tim Egan puts it, “This is your democracy on meth—the post–Citizens United world.”

* * *

Local TV stations across the country have come to rely on the booms in political advertising that come during critical election contests. In the ’70s, political ads were an almost imperceptible part of total TV ad revenues. By 1996, according to the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB), they had edged up to 1.2 percent. A decade later political advertising was approaching 8–10 percent of total TV ad revenue. For many stations, political advertising in 2012 could account for more than 20 percent of ad revenues, and in some key states far more than that. As former New Jersey Senator Bill Bradley put it, election campaigns “function as collection agencies for broadcasters. You simply transfer money from contributors to television stations.”

The 2010 election season saw record spending on broadcast advertising: as much as $2.8 billion. And that wasn’t even a presidential election year. Wall Street stock analysts can barely contain themselves as they envision the growing cash flow. Eric Greenberg, a veteran broadcast-industry insider, says, “Political advertising and elections are to TV what Christmas is to retail.”

Broadcasters aren’t about to give away the present they have received from the Supreme Court. The NAB has a long history of lobbying to block any campaign finance reform that would decrease revenues for local television stations, such as the idea of compelling stations to provide free airtime to candidates as a public-service requirement. The NAB’s prowess in Washington was summed up by former Colorado Representative Pat Schroeder, who said, “Their lobbying is so effective, they hardly have to flick an eyelash.” After the Citizens United ruling, the NAB actively opposed key provisions of the DISCLOSE Act, a measure supported by Congressional Democrats and a handful of reform-minded Republicans to roll back elements of the decision. But that’s not all. The group has even opposed steps toward the transparency that Supreme Court justices who backed the Citizens United ruling agree is vital but that might shame (or at least expose) the excesses of Super PACs.

In Iowa, where the race was delayed by wrangling over the caucus date, there were fears the money would not flow. But once the timeline was set, WHO, the NBC affiliate, along with another Des Moines station, took in nearly $3.5 million in the last weeks of 2011. A local station manager admitted he was prepared to interrupt his New Year’s Eve dinner to upload new political ads. In all, more than $12.5 million worth of advertising was purchased in the Iowa race, and December 2011 revenues for WHO were up more than 50 percent from December 2010. The driver in the frenzy of last-minute TV advertising in Iowa and New Hampshire was the Super PACs.

Super PAC advertising is not like traditional campaign advertising. As the scenario that played out in Iowa illustrates, Super PACs allow allies of candidates with the right connections to the right CEOs and hedge-fund managers to pile up money that can then be used not to promote that candidate but to launch scorched-earth attacks on other candidates. The scenario is particularly well suited to negative advertising. This warps the process in a perverse way, creating a circumstance where a candidate who is not particularly appealing to voters but who is particularly appealing to a small group of 1 percenters can, with the help of well-funded friends, frame a campaign in his favor.

The threat to democracy plays out on a number of levels. Candidates without the right connections may prevail in traditional tests—as Gingrich did with strong debate performances and Rick Santorum did with grassroots organizing and a solid finish in Iowa. But they are eventually targeted and taken out by the Super PACs, and the candidate with the right connections, in this case Romney, enjoys smooth sailing. In Iowa, roughly 45 percent of all ads aired on local TV stations: thousands of commercials, one after another, attacking Gingrich.

Negative advertising can be effective even if it does not generate a single new voter for the candidate favored by the Super PAC placing the ad. If negative ads simply scare off potential backers of an opponent, that’s a victory. Moreover, negative ads often force targeted candidates to respond to charges, no matter how spurious. And our lazy and underresourced news media allow the ads to set the agenda for coverage, thereby magnifying their importance and effect.

The most comprehensive research to date concludes that between 2000 and 2008 the overall percentage of political TV ads that were negative increased from 50 percent to 60 percent. And 2008 is already beginning to look like a tea party. The percentage and number of attack ads in 2010 were “unprecedented,” and they are increasing sharply again in 2012.

“I just hate it, and there’s so much of it,” Sarah Hoffman complained to a reporter at a Gingrich event in the Iowa town of Shenandoah. “Anytime they do anything negative, I just turn it off.” Gingrich emerged as a born-again reformer for about ninety-six hours during his Iowa free-fall, telling voters like Hoffman: “It will be interesting to see whether, in fact, the people of Iowa decide that they don’t like the people who run negative ads, because you could send a tremendous signal to the country that the era of nasty and negative thirty-second campaigns is over.”

If a signal was sent from Iowa, it was that many voters would rather switch off than try to sort out the attacks. With no competition on the Democratic side, and with conservatives supposedly all ginned up to choose a challenger for President Obama, Republicans confidently suggested that caucus turnout would rise from 119,000 in 2008 to as much as 150,000 in 2012. Instead, turnout was up only marginally, to around 122,000. If the maverick candidacy of Ron Paul had not attracted thousands of new voters to the caucuses—many of them antiwar and pro–civil liberties independents unlikely to vote Republican in the fall—the turnout would almost certainly have fallen to pre-2008 levels. “If all people hear are negatives, a lot of them are just going to ask, Why bother?” says Ed Fallon, a former Democratic legislator and local radio host in Des Moines who caucused this year as a Republican. “And they’re even more frustrated by the fact that the money for the negative campaigning comes from all these unidentified sources on Wall Street.”

The research of scholars Stephen Ansolabehere and Shanto Iyengar demonstrates that the main consequence of negative ads is that they demobilize citizens and turn them away from electoral politics. This fact is a “tacit assumption among political consultants,” they explain, arguing that the trend is toward “a political implosion of apathy and withdrawal.”

* * *

Were national and local broadcast media outlets to cover politics as anything more than a horse race and a clash of personalities, they might be able to undo much of the damage. But stations across the country—and the newspapers they often depend on for serious coverage—have eviscerated local reporting in recent years. Surveys suggest that news programs now devote far less time to political coverage than they did twenty or thirty years ago. To the extent that campaigns are covered, the focus is on personalities and the catfight character of the competition. So it was that when Gingrich complained about the battering he was taking from the Super PACs, the story was portrayed as a dust-up between a pair of candidates rather than as evidence of a structural crisis. In part, this is the fault of the candidates, who for the most part do not want to speak too broadly about Super PAC abuses in which they are engaging or in which they hope to engage.

Once it became clear that the media had no real interest in examining the problem, Gingrich quickly got with the program. Rather than make an issue out of campaign corruption, Gingrich’s own Super PAC, Winning Our Future, corralled a $5 million donation from the spare-change drawer of Las Vegas casino mogul Sheldon Adelson (listed by Forbes as the eighth-wealthiest American, with a $21 billion fortune) just before the New Hampshire primary. The plan was to launch a blitzkrieg against Romney. Here we finally get the proper metaphor for post–Citizens United elections: mutually assured destruction, with citizens and the governing process the only certain casualties.

Unfortunately, the media outlets that could challenge this doomsday scenario tend to facilitate it. The elimination of campaign coverage is masked to a certain extent because the gutting of newsrooms also encourages what sociologist Herbert Gans describes as the conversion of political news into campaign coverage. As campaigns have become permanent, so has campaign coverage. Such coverage is cheap and easy to do, and lends itself to gossip and endless chatter, even as it sometimes provides the illusion that serious affairs of state are under scrutiny. To someone watching cable news channels, it might seem that presidential races have never been so thoroughly exhumed by reporters. But the coverage is as nutrition-free as a fast-food hamburger. After a panel of “experts” finish “making sense” of Rick Perry’s debate performances, political ads don’t look so bad.

With the little news coverage that remains focusing overwhelmingly on the presidential race, Congressional, statewide and local races get little attention nationally or even locally. Not surprisingly, research suggests that political TV advertising is even more effective further down the food chain. “In presidential campaigns, voters may be influenced by news coverage, debates or objective economic or international events,” the Brookings Institution’s Darrell West explained in 2010. “These other forces restrain the power of advertisements and empower a variety of alternative forces. In Congressional contests, some of these constraining factors are absent, making advertisements potentially more important. If candidates have the money to advertise in a Congressional contest, it can be a very powerful force for electoral success.”

West’s point is confirmed by a simple statistic from the 2010 races: of fifty-three competitive House districts where Rove and his compatriots backed Republicans with “independent” expenditures that easily exceeded similar expenditures made on behalf of Democrats—often by more than $1 million per district, according to Public Citizen—Republicans won fifty-one.

To the extent that media outlets cover campaigns, they highlight the “charge and countercharge” character of the fight as an asinine personality clash between candidates. But the real clash is between money and democracy. And the media outlets that continue to play a critical role in defining our discourse are not objecting. They are cashing in. Meanwhile, citizens are checking out.

You can access all of The Nation‘s coverage of Citizens United by clicking here.