Political organizing is challenging work. You’re expected to keep up with the metrics and goals of your parent organization while convincing people, one by one, to help you push political leaders to make positive change. All the while, climate change continues, justices and Republicans strip people’s reproductive rights, and the news from Washington is relentlessly bad. It’s no wonder organizers are burning out.

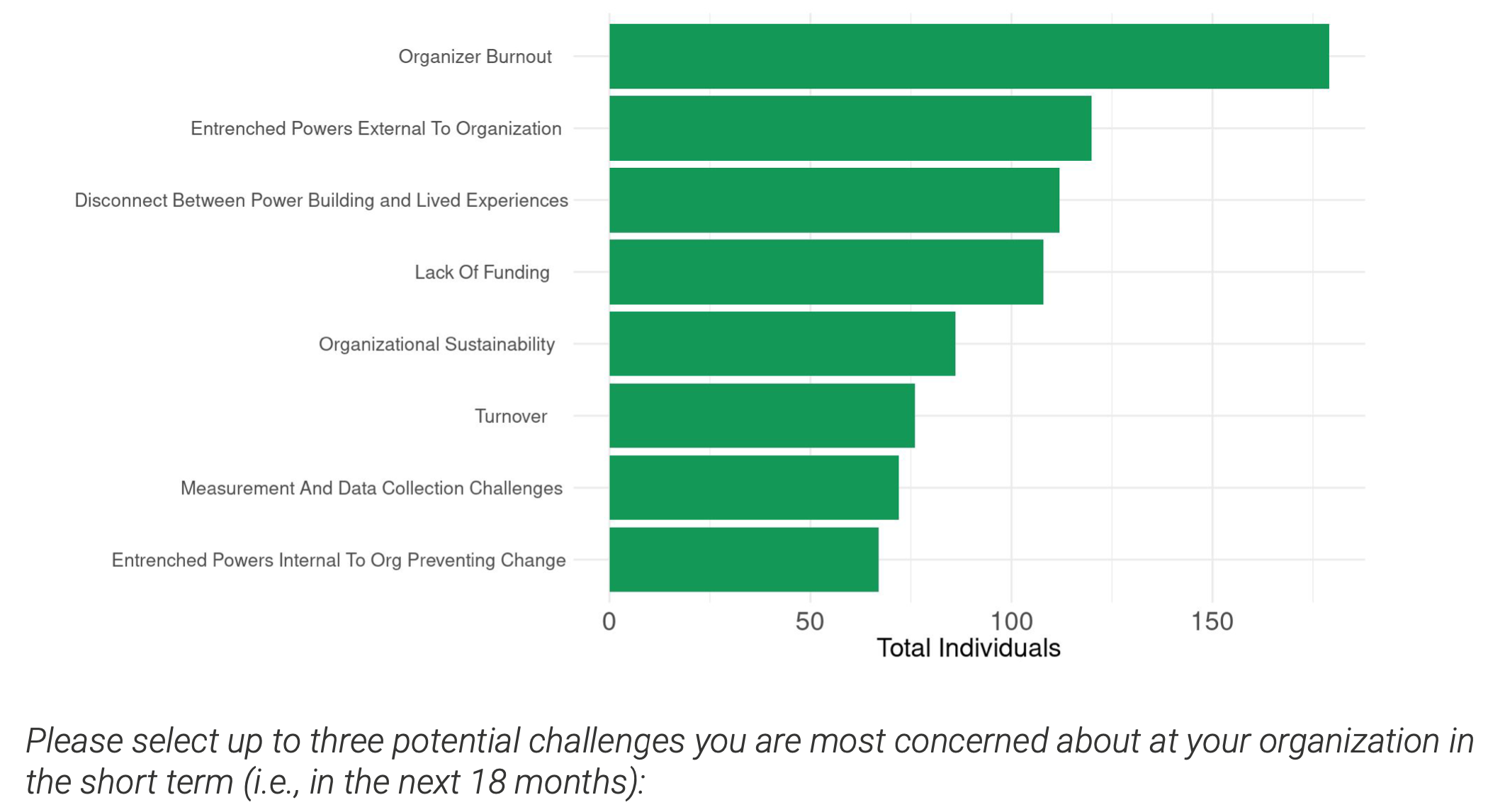

Fatigue is a major challenge facing organizers around the country, according to new polling from the group re:power. The poll, conducted by researchers Sam Gass and Maya Gutierrez, surveyed 349 organizers from across the country, asking them to list short-, medium-, and long-term concerns. The poll found that burnout, low pay, and institutional barriers to seizing power make up a trifecta of issues facing organizers at all time scales.

Karundi Williams, re:power’s executive director, says the poll should be understood as a devastating critique of the state of organizing. “We’re losing organizers, period, from the movement because of burnout,” she told me. “It’s a big fundamental problem.”

Polls don’t often focus on organizers, and even less on women of color in the space, Williams said. The goal of the survey was to bring their issues to the fore so that organizations can learn how to better serve them. After gathering responses on the online survey, re:power used demographic breakdowns to isolate topics and areas of concern for women organizers of color. The disconnect between power-building work and lived experiences is contributing to the broader burnout problem, she said, and “BIPOC women and Black folks were specifically pointing to the reality that the material and conditions of their lives aren’t changing no matter how much they’re doing this work in organizing the organizing world. So that stood out to us.”

Instability is not just a short-term problem among organizers. It leads to compounding problems with how political organizing works for the public and for staff. While a majority of the re:power poll’s respondents said they expected to still be in the field within six months to a year, only 32 percent believed they’d still be organizing in five years—a serious brain drain. Staff turnover presents organizers with more hurdles to overcome, leading to inconsistency both in the office and on the street. It’s hard to convince people of your mission when the faces of the movement keep changing.

Grueling hours are seldom offset by high compensation. According to data from ZipRecruiter, well over half of people in the field can expect to make between $18,500 and $34,000 annually—or between $9.49 and $17.44 an hour. Brandi Hernandez, an organizer in Wisconsin with the nonprofit Leaders Igniting Transformation, told me that she now works at an organization with adequate pay, but most people in the industry aren’t so lucky. She said organizers, faced with the crush of low income and high costs of living, are often forced to find supplemental jobs.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

“Anyone that’s an organizer needs a livable wage, because it is exhausting work,” Hernandez said, adding, “I’ve met organizers who do organizing, and then on top of that they have a side hustle. They’re out bartending or doing something else too.”

Organizer burnout is also being driven by the general state of things in the US, said Jeniece Brock, the policy and advocacy director for the Ohio Organizing Collaborative. Brock noted that a number of outside strains on communities of color are leading to a build-up of resentment and exhaustion—listing voting rights, redistricting, reproductive rights, environmental justice, and social justice as examples.

“There’s so many things that are coming down rapidly that specifically affect the Black, brown, and immigrant communities,” she told me.

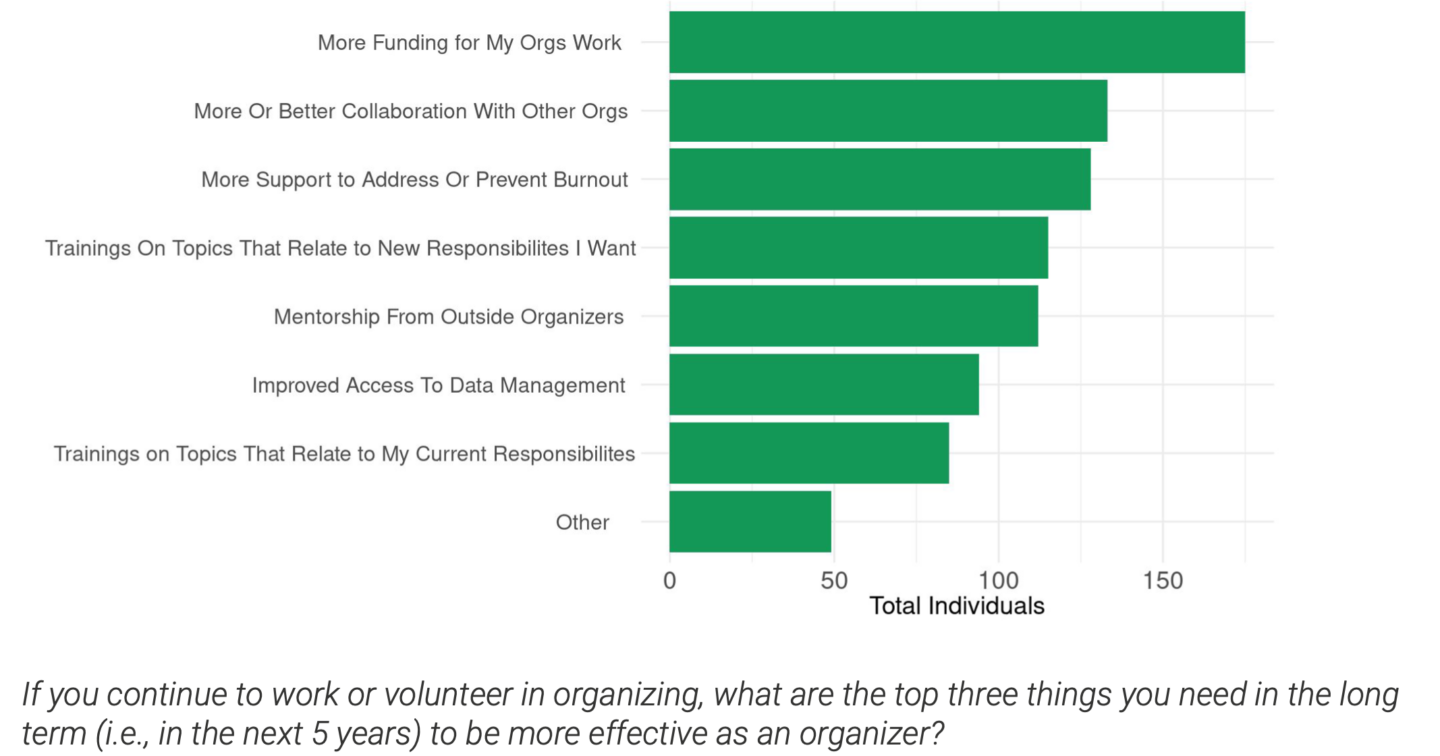

There is an effective path forward, and it’s a simple one: consistent funding. A surge in investment could fundamentally change a lot of the issues around burnout. But there are structural challenges. It’s difficult for organizations to lock in funding for the medium and long term. Funders tend to focus on what Karundi called a “shiny objects” approach to donating, where new organizations and fresh issues alike tend to pull more attention than steady, but unsexy, work. The report notes in its conclusion: “Multiple responses cited the challenges of ‘boom and bust’ funding, which can not only lead to gaps in funding, but can mean that funding comes too late to be of benefit, even during a boom.”

Such a boom-and-bust cycle reflects how funding can rely on—and turn on—short-term goals. This presents challenges, Williams said. While it can result in short-term success that can lead to longer-term donors, there are also the pitfalls of the breakneck speed of this kind of organizing and work. “Sometimes that funding can drive short-term burnout in terms of those sprints,” she told me.

Respondents also cited training and support for new skills as potentially beneficial to the continued work—all a part of the same push to establish a level of consistency in an industry that sorely lacks it. A constant churn of staffers who become organizers full of idealism and hope and then crash because of the onerous demands and low pay creates organizational inconsistency. It also has ramifications for effectiveness and efficiency, as time is constantly taken up to train new hires to do the work of burned-out organizers.

To Hernandez, that need for continuity is built into the work, because breaking down barriers to power takes time, and the results aren’t always tangible and visible at first. “Movements don’t happen within a year. They take a long time,” Hernandez said. “There are a lot of different campaigns that we’re working on.”

Funding often means that the short-term gains are just that. Without the steady, predictable funding of organizers, progress can easily and quickly fade away—and it often does.

“We lose a lot of the energy that was built within that cycle,” Brock of the Ohio Organizing Collaborative said. “We lose a lot of the continuity.”