The Catholic Women Priests Fighting for Reproductive Justice

The church forbids women to become priests, but RCWP-USA believes that they are aptly situated to minister on abortion and offer a new, progressive stance.

A woman receives a cup of wine from Rev. Victoria Rue during mass.

(Gina Ferazzi / Getty)Victoria Rue’s first abortion happened in a hospital in California, after the state legalized abortion just before Roe v. Wade. She was out of college, struggling to find work as an actress, and not in a steady relationship. The man who had gotten her pregnant—another young actor from one of her classes—offered to pay for her abortion. He came with her to the hospital, and was there when she woke up.

Rue’s second abortion was very different. She was still young, still struggling to find work, still not wishing to have a child. It was 1973, just after the legalization of abortion nationwide, but Rue did not have the money to pay for a hospital visit. Instead, she underwent a menstrual extraction, a procedure used to induce abortion in the early stages of pregnancy. It took place inside a storefront, not a hospital, and was much more affordable.

Rue didn’t speak with anyone before undergoing the procedure: She felt too ashamed to tell family or friends, and she had no relationship with the man that had gotten her pregnant. “I remember sitting in my Volkswagen across the street from it in a parking lot, just sitting there looking at the storefront across the street, preparing myself to go in,” Rue said. “And just feeling so alone.”

Many years later, Rue’s life looks quite different: She became a playwright, an activist, and a professor. She is also a Roman Catholic woman priest, part of an organization of women who have ordained themselves in the face of the church’s opposition. Most recently, she has become an outspoken pro-choice voice within the Catholic Church.

The institutional Catholic Church forbids women to become priests, citing the Bible’s record that Jesus only chose male apostles, as well as the nearly 2,000 years of precedent. These women practice as Roman Catholics, but most have been excommunicated by choosing to be ordained.

Roman Catholic women priests come to be ordained in a variety of ways: Several of the earliest—the “Danube Seven”—were ordained by a male bishop on the Danube River in 2002, and since then, many more have been ordained by female bishops across the world. Despite opposition from the Vatican, there are nearly 200 women priests in the United States and others in South America, Europe, Asia and Africa.

The Catholic Church believes abortion is murder, opposing all medical procedures where the purpose is to induce abortion. It has repeatedly affirmed this teaching, from the 1974 “Declaration on Procured Abortion” by Pope Paul VI to Pope John Paul II’s 1992 “Evangelium Vitae.” In response to a statement from 31 Catholic Democrats in the US House of Representatives, the church reaffirmed its opposition again in June. The congresspeople’s “Renewed Statement of Principles” was released on June 24—the one-year anniversary of the ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which allowed many states across the U.S. to severely restrict or ban abortions—arguing for a pro-choice Catholic teaching of abortion based on care for the poor, the priority of informed conscience, and the principle of religious freedom. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) responded by saying that the House statement “grievously distort[s] the faith” and that abortion violates the right to life “with respect to preborn children and brings untold suffering to countless women.”

Jamie Manson, president of Catholics for Choice, attributes this belief to a strong interest in the vocation of women first as mothers within the Catholic Church, and suggests that the church’s teaching is one of the most conservative in the United States. “No other religious tradition has a teaching on abortion the way the Catholic Church does, nor the teaching on contraception,” said Manson. “It’s very radical, even for conservative traditions like Evangelicals and Mormons.”

The Catholic Church’s stance on abortion has varied over time, however: Although the USCCB states that the church has always “distinguished themselves from surrounding pagan cultures by rejecting abortion and infanticide,” only in 1965 was abortion officially considered homicide; before, it was merely a sexual sin. The Catholic ‘right to life’ argument took shape alongside second wave feminists’ calls for legal abortion in the 1970s, leading to their stance today.

Now, abortion is as much a part of the lives of Catholics as anyone else: A majority of Catholics think that abortion should be legal in the United States, and approximately 24 percent of those who obtain abortions identify as Catholic.

Roman Catholic women priests believe that they are aptly situated to minister on the issue and offer a new, progressive Catholic stance on abortion, precisely because of their commitment to the religious tenets of Catholicism.

On June 21, 2023, the American branch of the women priests’ formal organization, Roman Catholic Women Priests-USA (RCWP), gathered for a historic forum to discuss abortion and reproductive justice three days before the anniversary of the Dobbs decision. While the topic of abortion was always a foremost concern for a progressive Catholic organization of primarily women, the Dobbs decision marked a renewed interest in advocating for an issue so fraught within the mainstream Catholic Church.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The solutions and ministries these women priests are working for are not traditional political activism. Central to the forum—and to their approach—is what these priests call accompaniment, an individual-focused approach they hope to adopt in order to be nonjudgmental spiritual advisors to those considering abortion or who have already undergone the procedure. The term comes from liberation theology, a Catholic ideology created by Peruvian priest Gustavo Gutiérrez, combining Catholic teaching with class politics. It is frequently invoked by progressive Catholics on matters of public health and social work for the poor. The term ‘accompaniment’ is also used by Latin American feminists to describe the process of being present with and supporting those seeking abortions.

No matter their personal beliefs on abortion—nor the beliefs of those they serve—these women priests’ stated goal is to offer impartiality and empathy, regardless of what the person considering abortion ultimately chooses.

Leading the charge is Rue, who has made it her goal to address the issue of abortion and determine how her organization might be a progressive force for change. Despite growing up religious and spending a year in a Catholic convent, Rue cites the women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s as her church after she drifted from Catholicism. Rue’s activism eventually led her to protest outside St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City as a part of Dignity New York, an LGBTQ+ Catholic activist group formed in response to the 1986 Vatican “Halloween letter,” which deemed homosexuality an “objective disorder.”

At this protest, like many others staged by Dignity New York, a Catholic mass was celebrated. These services were far different from those hosted within the walls of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The words of the service diverged from tradition: Source material included Walt Whitman as much as it did the Christian bible. The sacrament of communion centered around the notion that the bread being broken represented everyone, not just Jesus.

Rue had been asked by members of the group to co-lead such a service with an out gay Catholic priest and agreed. “I began to understand myself to be a priest,” said Rue. “And that I had been ordained by the people in the very act of celebrating mass, as opposed to the laying on of hands.” Years later, after learning about Roman Catholic women priests, Rue was ordained a deacon on the Danube river in 2004, and ordained a priest in 2005 on the St. Lawrence Seaway.

Rue worked as a professor at San Jose State University while also writing plays. In the immediate aftermath of the Dobbs decision leak, she began a project with fellow playwright Martha Boesing called “Voices from the Silenced: Pre-Roe Abortion Stories from Rossmoor.” For the play, Rue asked women in her senior living community who had had abortions to write their stories down for her, and she and Boesing shaped the roughly 30 responses into a play, told by seven women actors and a narrator who is a member of the pre-Roe underground abortion service provider the Jane Collective. The American Medical Women’s Association is showing the play to all of its coalitions including medical school students.

For Rue—and many members of RCWP—the commitment to being a woman priest is a simultaneous commitment to activism. In fact, one region within the RCWP organization is called the “Region for the Holy Margins,” a non-geographical group of women priests who have a particular interest in serving vulnerable communities. They see themselves as more than just female priests, but, rather, activists who seek systemic change within the Catholic tradition beyond just allowing women to be priests.

The Dobbs decision, for many of these women priests, was an inflection point in their activism, a moment in which the many causes they involved themselves in—women’s rights, racial justice, care for the poor, etc.—came to a head around a major political moment.

Despite enthusiasm from its members, the official RCWP organization has been disunited in its activist work, with a lack of consensus over their official stance on abortion and their ministers spread out across the country. The national organization meets only every few years, though the regions meet more regularly. “What RCWP has been unified in its online presence about is simply ordaining women. That’s it. That’s been the clearest ‘social justice’ piece that we’ve done,” said Rue. “We’re advocating for the presence of social justice in the forefront, as much as ordaining women.”

In the June forum, Rue presented a number of suggestions for how women priests might be able to support women considering abortion. They intend to educate and train themselves on reproductive justice teachings and use their national network to serve as clinic escorts, and to create a more formal process for women considering abortion to get in contact with and receive support from a woman priest.

This goal is personal for Rue, who wished she had had a woman priest to support her during her second abortion. Although no one she knew was there to support her, she recalled how the man performing her abortion called in his 12-year-old daughter, who held her hand during the procedure. “She really held my hand,” said Rue. “I’d never seen her before, but boy was I happy she was there.”

Such themes—physical presence, emotional support, and the ability to listen without judgment—came up again and again in the forum. The conversation also included a suggestion to ritualize abortion in order to help women better cope with the experience, as well as an emphasis on following up with the women afterward and continuing to support them. Many of the women priests gathered at the forum also hope to organize around an intersectional approach to abortion rights activism.

Much of the moral justification for women priests’ understanding of abortion and other social justice issues hinges on the Catholic concept of the “primacy of conscience,” the notion that each individual knows their circumstances best and can make moral decisions based on their own situations. During a second RCWP forum in July on reproductive justice, Jamie Manson and the women priest participants pointed to the choice Mary had in the Christian bible to say “yes” or “no” to her pregnancy, grounding her decision in autonomy. This understanding of conscience, they believe, is central to reproductive justice.

In the future, RCWP plans to continue speaking to experts in the field of reproductive justice and to consider the advocacy they hope to do as an organization. One of these plans for the future is to participate in a program spearheaded by Catholics for Choice, the revival of the Clergy Consultation Service, a cross-denominational group of American religious leaders that helped pregnant people obtain abortions before Roe made abortion legal nationwide.

“Faith communities have always been essential to political change” Manson said. “And I think the secular pro-choice movement has made a terrible mistake marginalizing those voices.”

For Rue—and the rest of RCWP—that political work looks very different from secular reproductive justice political activism. A key point Rue stressed over and over was that, in her view, women priests need not agree with abortion on a personal level, but instead merely provide a nonjudgmental, spiritual presence for pregnant individuals, whose beliefs on abortion also may vary greatly.

From the roots of her priesthood in LGBTQ+ activism to today, Rue believes that religious ministry and her activist work are not disparate at all, but intimately connected and mutually reinforcing. “I think the core of the many hats that I have worn and do wear is the body, particularly women’s bodies,” said Rue. “How could one be involved in anything that is anti-body, anti-women? All these issues come to bear, I think, on the beauty, and the grace, and the suffering, and the pain of the human body.”

More from The Nation

The “Save Chinatown” Coalition Goes on the Defensive in Philadelphia The “Save Chinatown” Coalition Goes on the Defensive in Philadelphia

The construction of a new basketball arena threatens to fill the neighborhood with more traffic and raise rents.

Human Rights for Everyone Human Rights for Everyone

December 10 is Human Rights Day, commemorating the anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), one of the world's most groundbreaking global pledges.

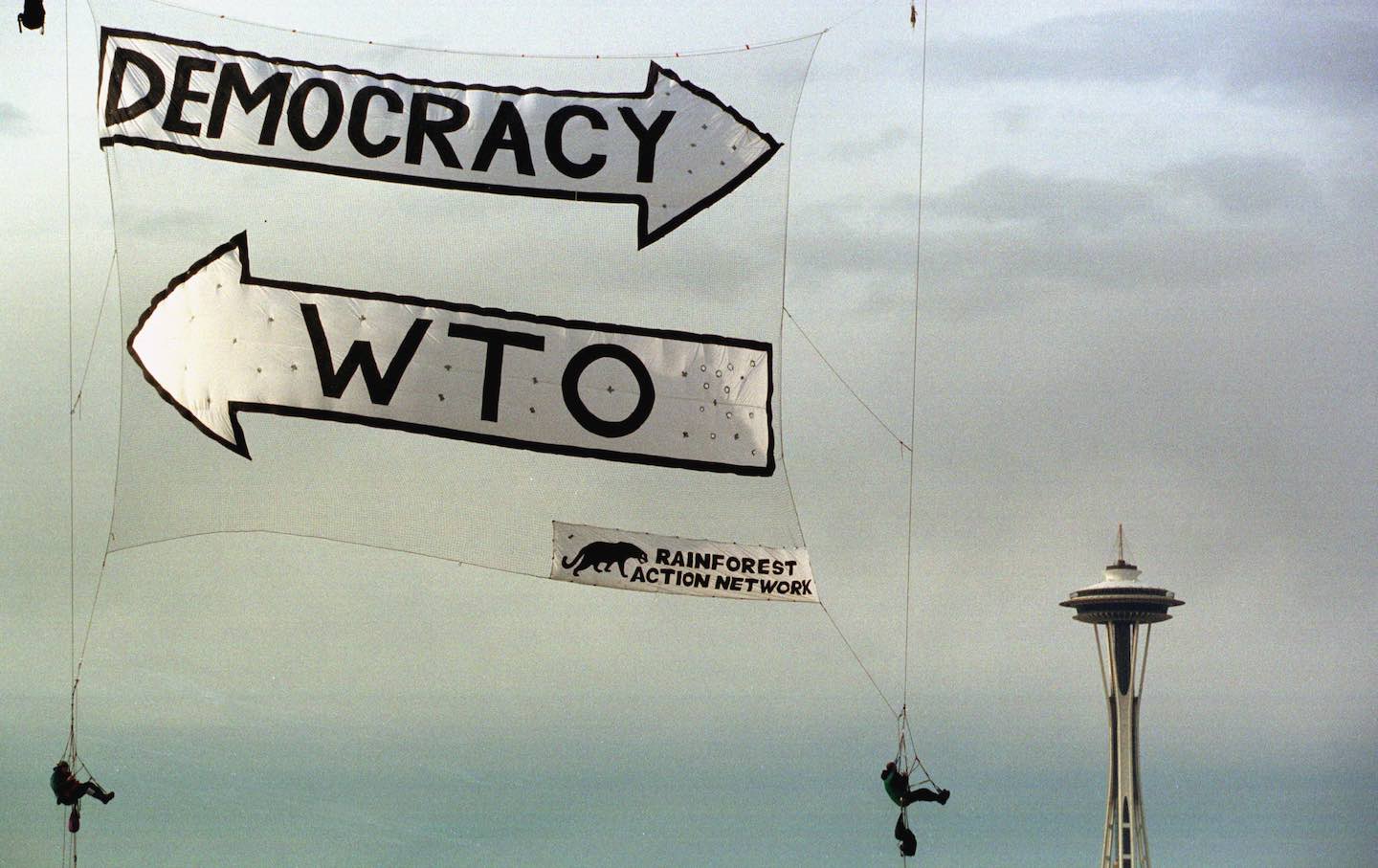

25 Years Ago, the Battle of Seattle Showed Us What Democracy Looks Like 25 Years Ago, the Battle of Seattle Showed Us What Democracy Looks Like

The protests against the WTO Conference in 1999 were short-lived. But their legacy has reverberated through American political life ever since.

Hollywood’s Vocal Actors Union Goes Silent on a Gaza Ceasefire Hollywood’s Vocal Actors Union Goes Silent on a Gaza Ceasefire

Amin El Gamal, head of SAG-AFTRA's committee on Middle Eastern and North African members, has advocated for a statement supporting a ceasefire in Gaza—so far without success

The Mirabal Sisters The Mirabal Sisters

Patria, Minerva, and María Teresa Mirabal were sisters from the Dominican Republic who opposed the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo; they were assassinated on November 25, 1960, und...

What Will a Peace Movement Look Like Under Trump’s Second Presidency? What Will a Peace Movement Look Like Under Trump’s Second Presidency?

An all-hands-on-deck approach to the coming world of Donald Trump and crew is distinctly in order.