The Struggle to Save Berkeley’s People’s Park

After a police raid in early January, razor wire was erected and homeless residents removed. “This is, unfortunately, something that’s not unique to Berkeley.”

Protesters during an event at People’s Park in Berkeley, Calif., in 2022.

(David Paul Morris / Getty)Around midnight on January 4, police commenced a military-like operation while much of UC Berkeley’s student body was off campus for the winter break. “Cops!” shouted out a few bystanders—tucked in tents and treehouses—who were tipped off about the move to close off what remains of the landmark People’s Park, minutes away from its university landlord.

Dozens of police had surrounded Luca, 22, and a few other community organizers, who were protesting and locked in the park’s mock kitchen, with hygiene products, cooking supplies, and propane tanks inside with them.

The dismantling of the structure began. A chainsaw was brought out and sparks flew. Smoke filled the area. Luca and their friends shouted to the figures decked out in riot gear with weapons ready to be drawn, hoping to warn them of the hazard the tanks posed—to no avail. Watching was Lisa Teague, a harm reduction advocate at the park. They begged officers to have the fire department “on standby.” The kitchen—tattered with graffiti, rainbows, and ink blots, with the Palestinian flag in a corner—began to see its last days.

“There was no safe way out,” said Luca, a recent UC Berkeley alumni. “We couldn’t go out through the roof because officers were standing at that entrance. It was terrifying.”

“It was a chaotic scene,” said David Snyder, a lawyer and executive director of the Bay Area–based First Amendment Coalition. “It happened very abruptly, and it happened very late at night. Figuring out who did what and when can prove to be a real challenge, and figuring those things out would be important for understanding whether the university crossed the line or not.”

The tensions between local activists and university officials over whether to establish 1,100 units of student housing and 125 units of supportive housing for unhoused individuals at People’s Park have rocked the nation’s most expensive college town, as state officials, Governor Gavin Newsom, and the 10-campus University of California system find themselves on the side opposite to the activist left in disputes over education, housing, and immigration.

Activists defending the park say they’re continuing a long-standing tradition of battling the UC and state to hold on to one of the last parks in the area that has provided community and public green space for decades. The site—whose legacy is steeped in the counterculture of the late 1960s—remains contested in a bitter legal dispute. But the most recent operation has roiled city leaders and galvanized a diverse coalition of younger and older activists who see Berkeley as a flashpoint for other forms of oppression taking place across the country.

In February 2023, a state appeals court halted the university’s project after hearing arguments from opponents that UC Berkeley had not properly conducted environmental reviews mandated by state law. An appeal remains in limbo at the State Supreme Court. The university says it has the right to fence off the property and that the operation and police presence is necessary for safety, citing “violence” by activists in the past like when fences were mounted in August 2022 and subsequently torn down.

The campus newspaper The Daily Californian called the operation on January 4 and the subsequent crackdown “dystopian.” Double-decker shipping containers have been erected around the park, topped off with security cameras and razor wire. Squads from the California Highway Patrol have been called in as well as UCPD, troubling local politicians and activists who worry that they aren’t barred by the city’s tear gas and pepper spray bans. Cars near the messy medley of barricades have been towed without notice. Residents nearby have been forced to show identification to access streets adjacent to their homes, according to news reports from student and local journalists.

Councilmember Kate Harrison—who is also running for mayor and resigning later this month—labeled the university’s shipping container operation a “Trumpian border wall,” alleging that the university deliberately avoided seeking the correct permits because they “did not want people to know they were going to move ahead.” She supports the project in theory.

The university has owned the 2.8-acre park since 1967, and has planned to construct housing and raze preexisting buildings in the past. Soon after the university took ownership, the vacant lot drew the attention of activists and fell into the wave of ‘60s radicalism, as ponds, botanical reclamation, and gardening projects sprung up.

A subsequent showdown in May 1969 between protesters and as many as 2,000 police officers—summoned by then-Governor Ronald Reagan—would cement the park as a battleground for space between activists and the university, when police opened fire on young protesters who shared a similar mission to current park supporters today. Later attempts by the UC to create soccer and volleyball fields, parking lots, and housing would fail. Despite successful efforts to achieve federal recognition for the park, activists charge that the university has persisted in its effort to continue development.

“Cal has the effrontery to accuse us—we who fought for diversity and inclusion—of being retrograde NIMBYs who oppose opening the college’s doors to the deserving underserved,” organizers with long-standing ties to the park wrote in January for The Nation. “Meanwhile, the university has never accepted responsibility nor apologized for its behavior down these five decades—behavior that largely created the problem it now blames on us.”

The militarization of the park and the surrounding area in part spurred Cecilia Lunaparra, a fourth-year student at UC Berkeley, to run for the City Council in a special election in April. She’s been frustrated by city politics, and she and fellow activists see parallels in the city’s treatment of activists, the “Cop City” protests in Atlanta, and the defiance of the Supreme Court by Texas Governor Greg Abbott as he continues to support the installation of barbed wire across the US-Mexico border.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Despite resolutions from the student government defending the park, university officials have brandished polls from late 2021 and mid-2022 that show a majority of the student body in support of building housing at the park. “That didn’t say anything about the literal military occupation of District Seven. It didn’t say anything about shipping containers with barbed wire on the top. It didn’t say anything about the history of People’s Park or the mutual aid that happens right there,” said Lunaparra.

“The militarization of an entire neighborhood that is home to so many unhoused people, especially people of color, queer and trans people, young people, is absolutely awful,” she told The Nation. “This is, unfortunately, something that’s not unique to Berkeley, this is something that happens everywhere across the country that the most vulnerable and marginalized people in our communities are forced to face.”

Meanwhile, supporters of the project—including pro-housing advocates in the community—have argued that vandalism and spiraling crime require a strong police presence. Though activists doubt their commitments, supporters have also cited the UC’s promise to build housing for unhoused individuals at the site and make space for the park to still be honored. “It will be done and we are putting it all on the line with that commitment, no ifs, ands, or buts about it,” Dan Mogulof, a UC Berkeley spokesperson said.

About two hours after the operation had commenced, the site was cleared. The shipping containers were mounted. A ladder connecting a tree house to the kitchen was severed. Seven protesters, Luca among them, were cited and released. A handful of homeless park residents accepted transitional housing.

University officials acknowledged they were trying to “maintain a certain degree of secrecy,” during January’s operation. Mogulof avoided direct questions about whether the local fire department was on-site, but he said they had been involved in security consultations beforehand. Many of the barriers around the shipping containers have since been removed, he said, though concerns about bike lanes and appropriate space still linger in the campus community.

Both Mogulof and People’s Park supporters appeared to share an understanding that Berkeley was changing, losing some racial and ethnic diversity while becoming more affluent. Though his response signaled a key difference between the left’s insistence on remembrance and the university’s effort to change with the times: “With the pandemic, more and more of Berkeley became seen—by particularly sort of upper-middle-class young families—as a place where they could send their kids to public school and therefore save their money for a house.”

“We may be in disagreement about the extent to which the past can and will still be honored and commemorated and celebrated,” he said. “Even in the context of a park that has changed in terms of how it looks, we don’t believe that the best way to honor history is to leave things frozen in time.”

The park is now “almost unrecognizable,” according to one news report, with construction equipment clearing debris and razing the terrain, in a move activists worry goes further than current permits for barriers allow. Luca has had nightmares all of January. “That’s just to be expected,” they said. For now, they’ll continue helping out at the “People’s Free Store,” where organizers pass out donated clothes, allergy medicine, and hygiene kits.

The war in Gaza has also motivated young activists at the site to hold pro-Palestine protests in support of the park, as attendees ate home-cooked meals and broke out in song and chants. Candlelit vigils, memorials and concerts are now a regular occurrence, as supporters mourn the park they have cherished for decades. “The same forces that are attacking People’s Park,” said Jonah Gottlieb, a UC Berkeley student and organizer with the campus chapter of the Young Democratic Socialists of America, “are attacking the left and attacking people’s basic needs everywhere.”

More from The Nation

The “Save Chinatown” Coalition Goes on the Defensive in Philadelphia The “Save Chinatown” Coalition Goes on the Defensive in Philadelphia

The construction of a new basketball arena threatens to fill the neighborhood with more traffic and raise rents.

Human Rights for Everyone Human Rights for Everyone

December 10 is Human Rights Day, commemorating the anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), one of the world's most groundbreaking global pledges.

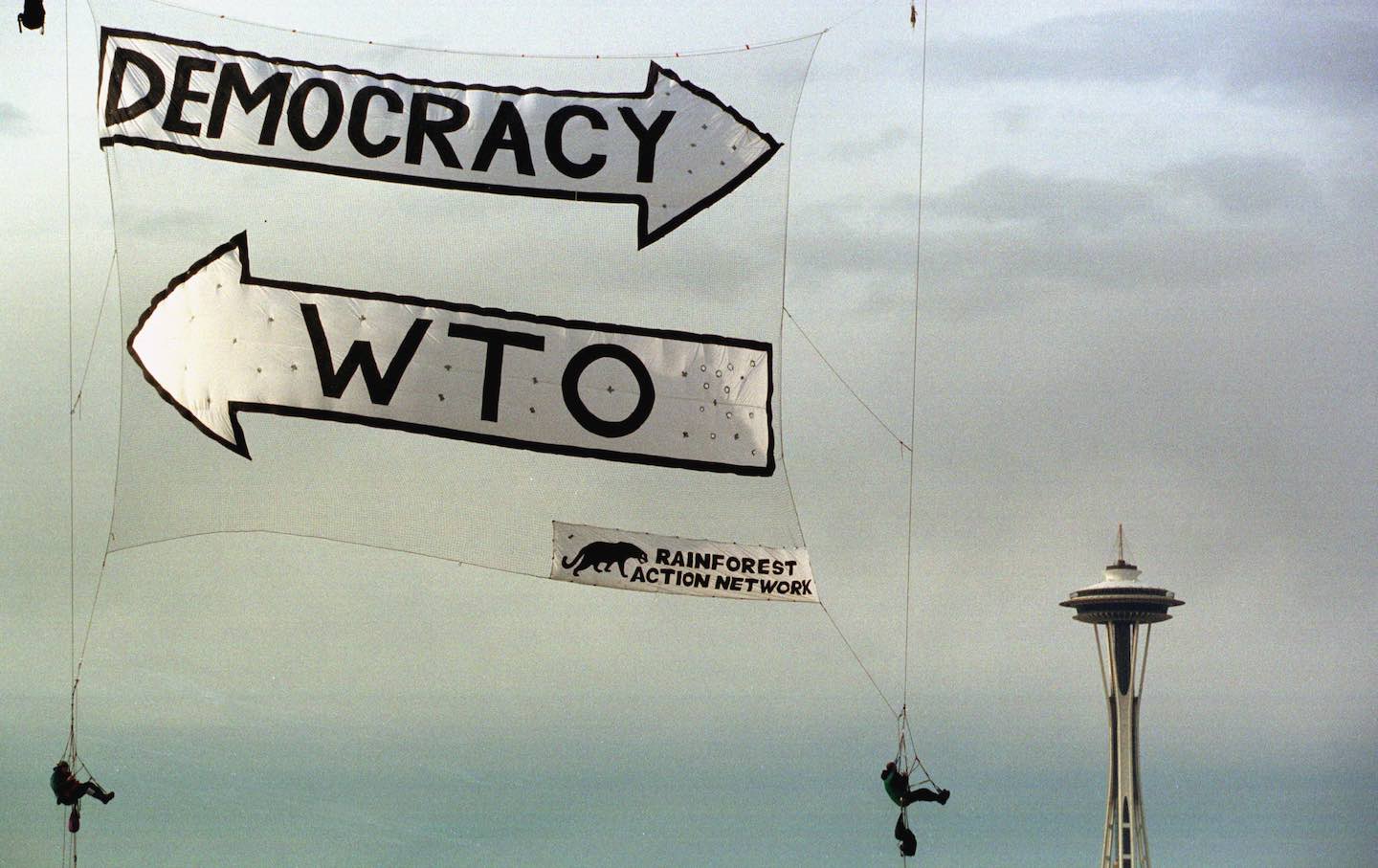

25 Years Ago, the Battle of Seattle Showed Us What Democracy Looks Like 25 Years Ago, the Battle of Seattle Showed Us What Democracy Looks Like

The protests against the WTO Conference in 1999 were short-lived. But their legacy has reverberated through American political life ever since.

Hollywood’s Vocal Actors Union Goes Silent on a Gaza Ceasefire Hollywood’s Vocal Actors Union Goes Silent on a Gaza Ceasefire

Amin El Gamal, head of SAG-AFTRA's committee on Middle Eastern and North African members, has advocated for a statement supporting a ceasefire in Gaza—so far without success

The Mirabal Sisters The Mirabal Sisters

Patria, Minerva, and María Teresa Mirabal were sisters from the Dominican Republic who opposed the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo; they were assassinated on November 25, 1960, und...

What Will a Peace Movement Look Like Under Trump’s Second Presidency? What Will a Peace Movement Look Like Under Trump’s Second Presidency?

An all-hands-on-deck approach to the coming world of Donald Trump and crew is distinctly in order.