Should People’s Park Be Consigned to the Ash Heap of History?

Many argue that after five decades of resisting the University of California’s repeated attempts to reclaim the park, it’s time to let go of the past and move on. We disagree.

Berkeley, Calif.—One of the last great battles of the 1960s—the struggle over the iconic People’s Park, founded in 1969—is now all but over. Despite an unresolved, still-to-be-argued lawsuit, now before the California Supreme Court, to prevent the University of California–Berkeley from building a $312 million 1,100-bed student dormitory and 125 units for low-income and formerly unhoused people on the site, the university acted with dispatch to crush any last vestige of opposition. The bells of the university’s Campanile had barely finished tolling the start of 2024 when Cal ordered a midnight operation, while students were away on winter break, to erect a double stack of 160 shipping containers, topped by razor wire on one end of the 17-foot-high metal wall, with multiple surveillance cameras. Hundreds of law enforcement officers, some in riot gear—many drawn from the California Highway Patrol and others from adjacent counties and municipalities—were mobilized to successfully barricade the contested 2.8-acre park from any possible protesters. Bulldozers were deployed. Many of the few remaining big trees were felled. About 60 protesters mounted a vigil overnight until police ordered them to leave, arresting seven for trespassing and failing to disperse.

UC Chancellor Carol Christ, who retires later this year, hailed the move as a “necessary step” in preparation for “when we are cleared to resume construction.” She sees her persistent effort to doom the park and build much-needed student housing on the site as “one of the most important things I’ve done” during her tenure. Of the 10 campuses in the University of California system, the flagship Berkeley campus provides the lowest percentage (23 percent) of student housing. Chancellor Christ has the support of Democratic Governor Gavin Newsom and the state legislature, and of Berkeley’s Mayor Jesse Arreguin—and perhaps most Berkeley residents. Many believe that after five decades of resisting the university’s repeated attempts to reclaim the park, it’s time to let go of the past and move on.

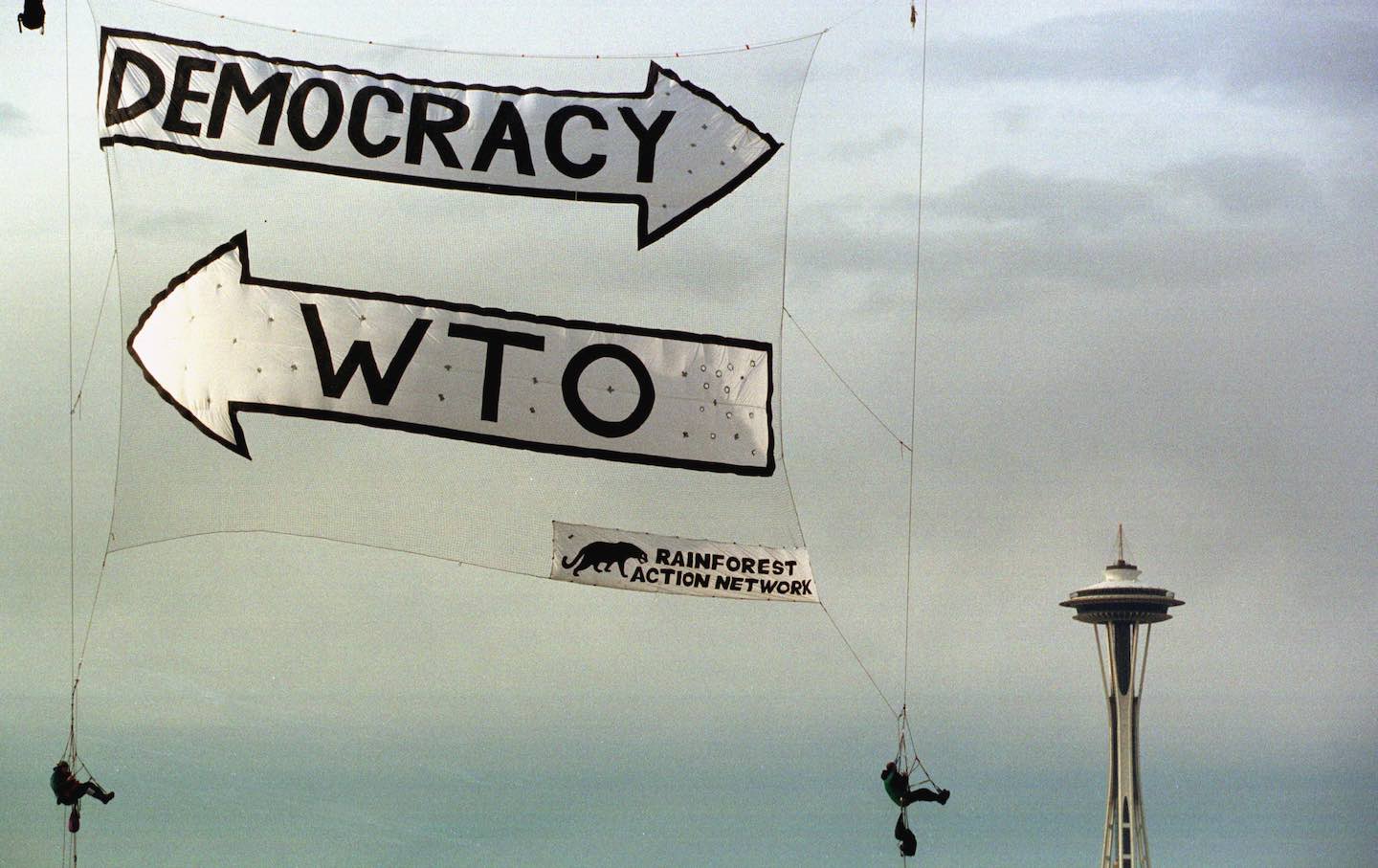

We disagree. What’s at stake is history and who gets to make and write it. For years, Berkeley, a small American hamlet, has been a harbor for upstart students who won for it an outsize international reputation as a magnetic pole of rebellion. The San Francisco Bay Area more generally was engulfed by multiple and successive student protests. The most notable included the anti-HUAC protests of 1960, the great civil rights sit-ins of the spring of 1964 at the Sheraton-Palace Hotel in San Francisco, and the Auto Row demonstrations seeking an end to racial discrimination, which began in late 1963 and continued through the spring of 1964.

The Free Speech Movement erupted here in the fall of 1964, followed by one of the nation’s first teach-ins, organized by the Vietnam Day Committee in May 1965; and, three months later, the efforts to block troop trains passing through Berkeley. In 1966 came the founding of the Black Panther Party in Oakland followed by the riotous anti-draft demonstrations in Oakland in 1967, then the use of tear gas to disperse the May 1968 demonstrations in solidarity with striking French students, followed by the violent effort to break the Third World Liberation Front strike at Cal in February 1969. All this culminated in the ruthless suppression of People’s Park protesters in May 1969.

People’s Park, at its best, was an expression of the utopian yearnings of a generation that sought to make a better world. The National Trust for Historic Preservation supports the park’s preservation, and notes that it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and believes People’s Park to be “nationally significant for its association with student protests and countercultural activities during the 1960s.”

The housing issue is a red herring. The university has always had the option of building needed dormitories on campus, as UCLA is doing, but it steadfastly refuses to do so. Thirteen other sites, suitable for building dorms, are also owned by the university, including one just a block west of People’s Park. Because Cal insists on building on People’s Park, which is listed on the National Register of Historical Places and refuses to submit to federal protocols governing construction on such sites, no federal funding will be forthcoming for supportive low-income housing—funding that would be available for alternative sites not on the register. With respect to student housing, the fight over the future of the park is as needless as it is divisive.

Once, in 1967, there were rental homes on the lot that became People’s Park. But the university razed them to rid itself of the student occupants whose radical politics the university detested. Cal then abandoned the lot, which became a muddy eyesore and a de facto parking lot, and stayed that way, by virtue of the university’s indifference, for nearly two years. When a group of mischief-makers and radicals, including ourselves and hundreds of others from all over Berkeley, began to build a park, the university surrounded the space with a chain-link fence in the dead of night and a rebellion erupted. Cal’s overseers, with the encouragement of then-Governor Ronald Reagan who’d been elected in part on his promise to “clean up that mess in Berkeley,” then attacked those of us seeking to defend the park, using hundreds of armed police, firing shotguns with live rounds of buckshot, killing one bystander (James Rector) and blinding another (Alan Blanchard), arresting hundreds (and beating them while in jail) on bogus charges that were ultimately dropped. The date was Thursday, May 15, 1969, and would be remembered as Bloody Thursday.

Martial law was declared. A National Guard helicopter indiscriminately sprayed military-grade tear gas over the campus, causing elementary schoolchildren to sicken and vomit many blocks away. Then, for the next 50 years, Cal allowed the plot of land to languish, becoming a site of the unhoused, the deranged, and the forlorn. Today, Cal has the effrontery to accuse us—we who fought for diversity and inclusion—of being retrograde NIMBYs who oppose opening the college’s doors to the deserving underserved. Meanwhile, the university has never accepted responsibility nor apologized for its behavior down these five decades—behavior that largely created the problem it now blames on us.

We have models elsewhere in Berkeley of how public and community greenswards thrive without the problems that have plagued People’s Park. Just look to Willard Park, a few blocks away, or to the Ohlone Park along Hearst Avenue below Martin Luther King Jr. Way, both largely free of open drug use, crime, and homeless encampments. But the university has steadfastly blocked the City of Berkeley from curating the park. The university is clearly guilty of bad faith. Yes, we may lose—not least because the university can outlast our generation, now bent by age, who built the park. We are no longer as physically able to fight for it as robustly as we wish. But do not doubt that a grave wrong is being committed against the past in the name of a future the university wishes to dominate.

Finally, to add insult to injury, the university says it will put up plaques, perhaps even exhibits to adorn the new dormitory so students will know the park’s history. We may well lose the fight to preserve and revivify the park—after all, Berkeley has always been the Republic of Lost Causes, and this is one of the great ones—but we’ll be damned if we also cede to Cal the right to tell the story of our rebellion. A struggle for memory and against forgetting is at the heart of the battle over People’s Park. A half century after Bloody Thursday, its legacy is still not well understood. A more subtle sense of what a historical moment contains is needed. Perhaps such an understanding will mean that the moment of exhausted possibilities is not yet at hand.