Sexual desire had no better advocate than Amber Hollibaugh. If that sentence lands strangely now, it is because Amber, a self-described “lesbian sex radical Marxist ex-hooker incest survivor rural Gypsy working-class poor white trash high femme dyke” (no commas), spent a lifetime breaking silences around sex, insisting that not only is ecstasy (and the wish for it) fundamental to human being but that any political movement that fails to grasp the totality of people’s complex desiring lives will never achieve the goal of liberation. When she died on October 20, at 77, her mourners spanned generations of freedom dreamers whom she had inspired and for whom the goal remains. But “advocate” is also too narrow a word.

Amber lived a rangy life. She was involved in the civil rights, the anti-war, and the women’s and gay liberation movements. Along the way, she joined a Marxist study group. Along the way, she found that exotic dancing and hooking brought better money, hours, and flexibility to support her activism than scrubbing office floors, picking tobacco, or working the night counter at a doughnut shop. She was present in San Francisco in the heady days of the lavender left, meeting and marching and cofounding the Lesbian and Gay History Project, and discovered her power as a public speaker, debater, and leader during the late-1970s backlash to gay visibility. She was present in early Second Wave feminism, organizing around women’s issues and prison issues, particularly involving lesbians, and developed her incomparable voice as a writer during the internal backlash typified by middle-class feminism’s sex-negative obsessions and Betty Friedan’s excoriation of “the lavender menace.” Her experiences in the grassroots campaign to defeat the Briggs initiative in 1978 (which would have banned homosexuals from teaching in California schools) and at the Barnard Conference on Sexuality in 1981 (which generated the landmark anthology Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality) profoundly shaped her public trajectory.

In the early 1980s, she wrote for the New York Native and The Village Voice, spoke at The Nation’s Writers Congress in a packed meeting on pornography. Her published conversations with other sex radicals—especially “What We’re Rollin’ Around in Bed With,” a discussion of butch/femme experience, with Cherríe Moraga—remain striking for their frankness about erotic imagination and practice. The political has never been so personal.

During the AIDS crisis, her documentary The Heart of the Matter examined women’s vulnerability before that was common. She produced videos and educated about AIDS for New York City’s Human Rights Commission, and founded the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) Lesbian AIDS Project when people said “everyone knows lesbians don’t get it.” She contributed to this magazine’s “Queer Nation” special issue, edited by Andrew Kopkind in 1993; spoke widely on class, race, risk, and the changing face of AIDS throughout the 1990s; engaged with trade unions; was a senior strategist at SAGE and the National GLBT Task Force, discussing sex and aging. In 2002 she cofounded Queers for Economic Justice, explicitly anti-capitalist and centered on the inequities and gender conformism that hit poor queer people hardest. She established a Queer Survival Economies project at Barnard that reflected the multiple strands of experience and identification that her 2000 book, My Dangerous Desires: A Queer Girl Dreaming Her Way Home, handles with bravura.

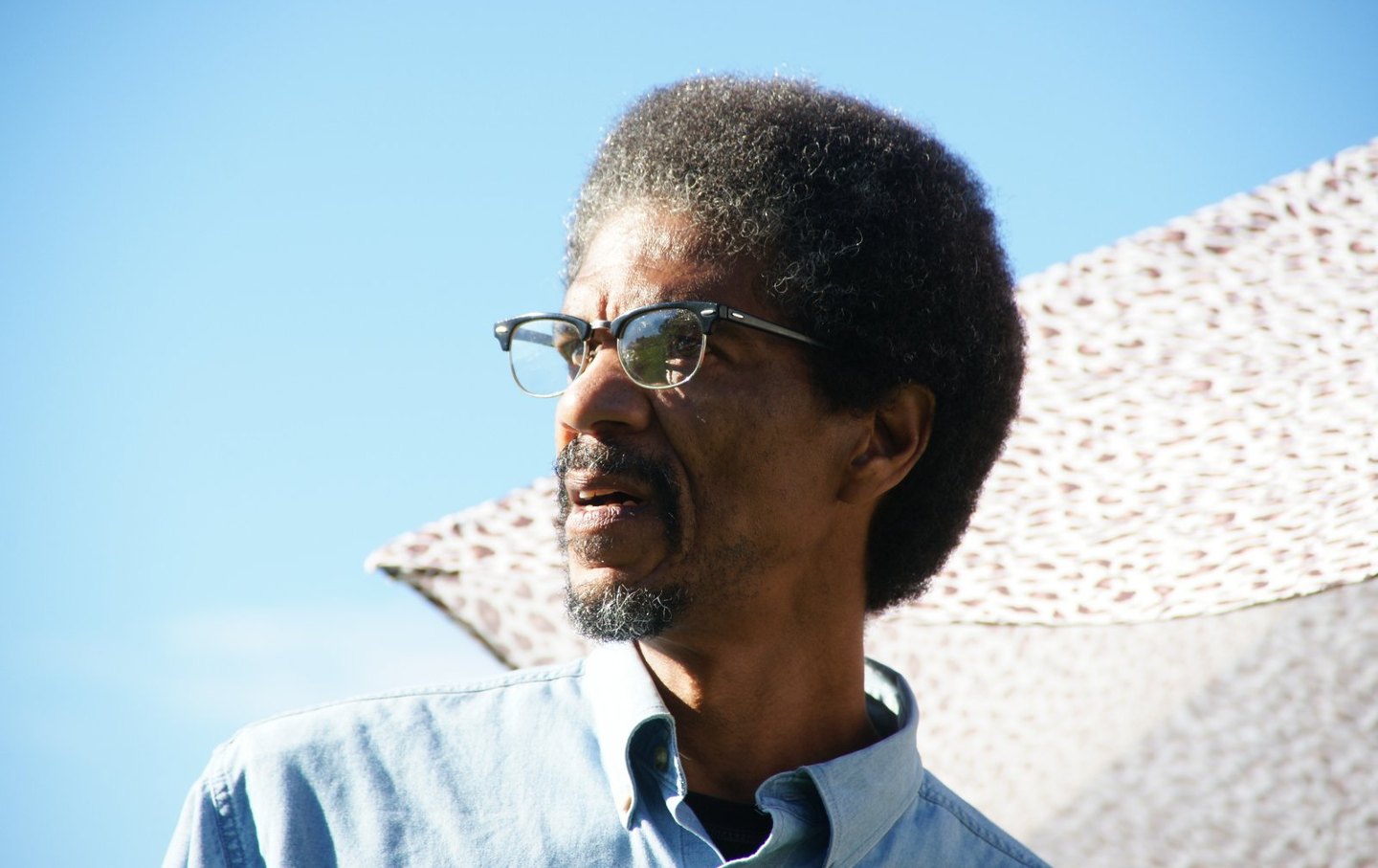

A rich radical life, which only hints at the woman Amber was and her luminous presence in the world: “relentless.… maddening.…dazzling,” as her partner, Jenifer Levin, wrote after her death.

Amber’s laugh was like a thunderclap in the sun, a bright, sharp “Ha!” In salutation, she’d say, “Hi, doll!” Stylistically, she said, she felt most akin to drag queens. She spoke with her hands, beautiful, manicured. Her voice could glide from solemn to raucous in the service of a deep political and emotional intelligence. “She was one of the warmest and most savvy activists in the movement,” Richard Goldstein, who’d been her editor at the Voice, recalled, “someone who led with empathy rather than ideology, though her commitments were evident in everything she wrote. Not an easy balance to maintain.”

Amber Hollibaugh was born in Bakersfield, Calif., in the summer of 1946, to an Irish mother and Romany father whose life’s only constant was poverty. Complicated, crafty people—respectively, a seamstress and Avon lady (among other jobs) and a construction worker and mechanic (among other jobs)—they were survivors, who bore slights for their mixed-color union, nourished a bitter humor, told fabulous tales, reveled in the speed and leather scent of racing motorcycles, loved their daughter, hurt and scared her too, and ultimately made it possible for her to imagine a different future. Many of Amber’s stories returned to the well of growing up. A memorable one is of her mother spotting an ad for boarding schools in a women’s magazine, furiously writing applications, winning Amber a scholarship for “low-achiever/high-IQ” students to the American School in Lugano, Switzerland. Amber learned great books there, and class humiliation. She lasted a year, but before she left, her favorite teacher, the son of Lebanese immigrants, counseled that her sorrows were not just personal, and gave her The Communist Manifesto. She returned home with books and questions, and then, while still a teenager, she ran away.

“I wanted everything—differently”, she wrote. Ecstasy, yes. Love, yes. Possibilities in a world that offered too few to so many, yes. A break from shame and fear, yes. Safety, yes. Liberation from the binds that had constrained her mother, brewed her violence and griefs, yes; from the structures that exhaust people, steal their time, diminish their bodies, try them for their color or affections, deform their own wanting and joy, yes. Revolution, hell yes.

The Switzerland story she told not as the dramatic turning point in a heroine’s romantic saga. Rather, it’s a parable of fluky encounters and life-as-struggle: Amber was out of place at that school, in her family, in her own fantasies, which terrified her. She would be out of place in left groups, where she kept her sex work a secret; in middle-class circles, where she masked the extent of her wanting; in lesbian and feminist political meetings, where butch/femme couplings were derided as parodies of heterosexual gender roles. Her earliest lesbian lovers were working-class butch women who belonged to an older world of bars and pleasure scenes. In their embrace, she started to find herself, to construct her high femme identity in the play with power and surrender, a woman loving women in a “gender-fuck” utterly “extraordinary.” Her most revealing writings are about becoming… a woman, a confident sexual person, a femme whose desires and butch partners evidenced multiple ways of being a woman, a pasionaria who recognized heterosexism, with its command—Here is a woman; here a man—as one in a constellation of oppressive systems that blare: No way out. It took a while, she wrote, but fathoming herself allowed her finally “to chart my life and comprehend the lives of others,” including her parents. Hence the empathy. Hence the desire to change the world.

I remember our first meeting, to talk about working-class girls in sex trouble. No one spoke like her. She let the light in.