What Happens to the Educators When the Schools Have Been Destroyed?

Hamada Abu Layla spent 22 years earning three degrees from Gaza universities. Now they mock him from a garbage dump.

Islamic University in Gaza, October 16, 2025.

This piece is part of A Day for Gaza, an initiative in which The Nation has turned over its website exclusively to voices from the Gaza Strip. You can find all of the work in the series here

“These certificates were supposed to open doors, not remind me of what I’ve lost,” says Hamada Abu Layla, 45, holding his three university degrees.

It is January, 2026, more than 90 days after the ceasefire between Israel and Hamas, and Abu Layla is standing amid piles of garbage bags in Al-Yarmuk, a dump in central Gaza City; it has been his family’s home for the past few months. Unable to return to Beit Lahia, where he once lived, he spent days searching Gaza City for vacant land to pitch his tent on. After finding none, he finally erected it inside Al-Yarmuk.

“It’s very bad—a pure health hazard where all of Gaza’s waste gets dumped,” he says.

Abu Layla lives in Al-Yarmuk with his wife and five children. They share the site with rodents, insects, snakes, and stray dogs that pound the fabric walls at night, terrifying the children and keeping them from sleeping. His children have developed skin rashes from insects.

A Day for Gaza

-

A Ceasefire in Name Only

-

The Gaza Street That Refuses to Die

-

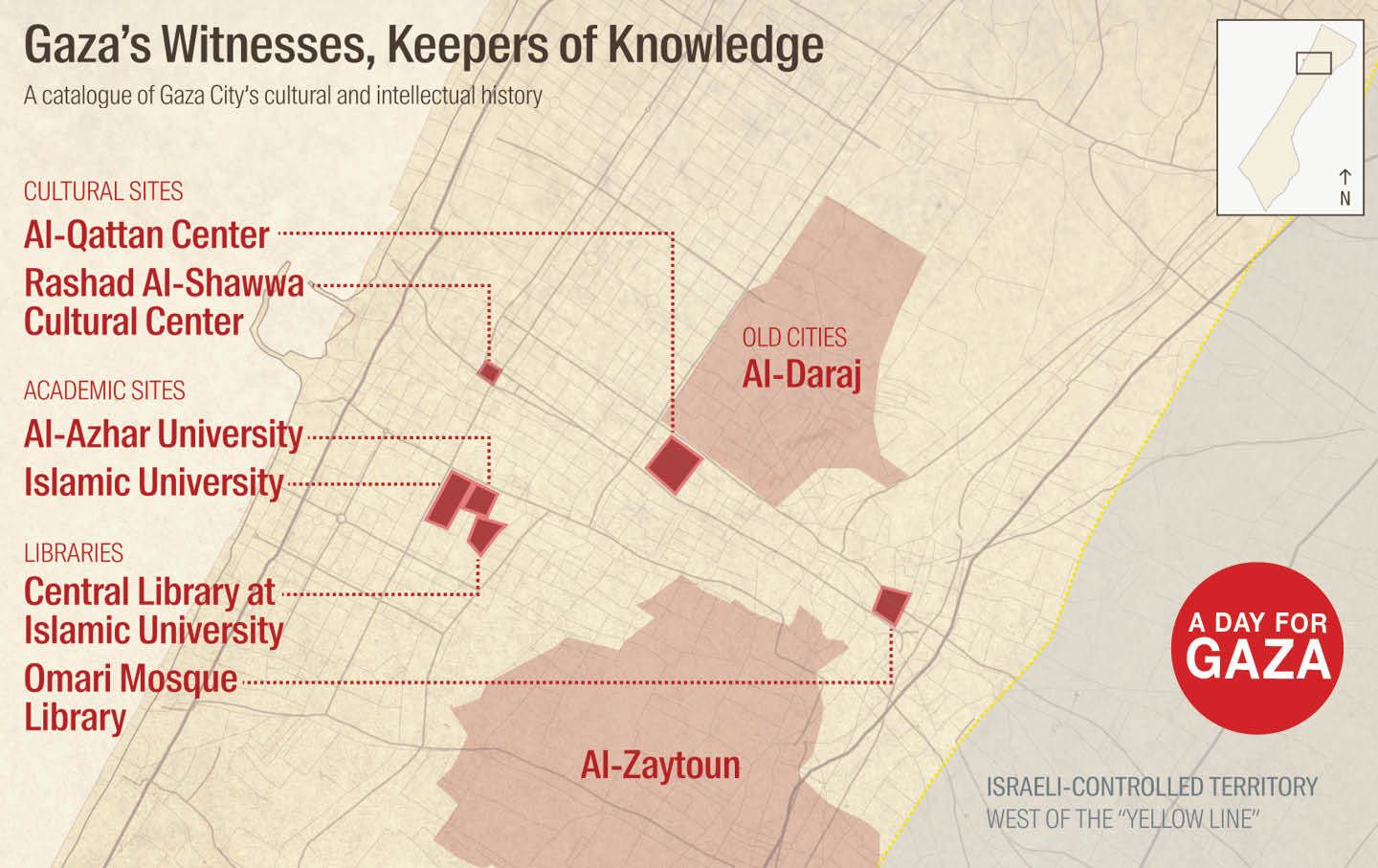

A Catalog of Gaza’s Loss

-

My Sister’s Death Still Echoes Inside Me

-

What Gaza’s Photographers Have Seen

-

How to Survive in a House Without Walls

-

What Edward Said Teaches Us About Gaza

-

What Happens to the Educators When the Schools Have Been Destroyed?

-

At the Doorstep of Tomorrow

-

“We Have Covered Events No Human Can Bear”

Once, less than two-and-a-half years ago, Abu Layla had his own apartment—in a building where his parents and siblings also lived—and spent his days lecturing at Gaza’s Islamic Da’wa College. As a younger man, he graduated first in Palestine in Islamic Sharia from this university, and then went on to earn diplomas in information technology and mathematics.

But the war has taken all of this from him. The Israeli army bombed his Beit Lahia apartment building, killing both his parents and his siblings, and only Abu Layla, his immediate family, and one brother survived. They fled without burying the dead, who remained under rubble, and have not been able to return. Beit Lahia, which lies behind the “yellow line,” is now under Israeli military control.

Also lost to the rubble are Abu Layla’s professional dreams: the days he spent lecturing to students, passing down his knowledge to the next generations. His credentials, earned over 22 years, mock him from a trash heap.

Now, instead of teaching students, Abu Layla’s work consists of survival: “I stand in water lines and charity kitchens for food. It’s mentally and physically exhausting, but I must do it to keep my children alive.” It’s the same routine that most Gazans are forced to perform.

“I imagine I’m living inside a nightmare and can’t wake up,” he says. “Before the war I had a house, family, good social and economic situation. That’s the past now.”

Abu Layla is among the survivors of Gaza’s devastated intellectual class. Before the war, Gaza was known as a famously education-focused society, with a literacy rate of nearly 97 percent and a storied intellectual tradition. Seventeen universities and colleges sprawled across the Strip, many with multiple campuses, educating the next generation of Palestinians. For these students, as well as for their teachers, college wasn’t just a way station on the way to a career but a commitment born out of the deep conviction that learning is a tool of resilience—a means to preserve national identity, a fundamental investment in human development, and a promise to the future despite poverty and blockade.

But the war destroyed much of that, silencing some of the brightest intellectual minds while knocking down the institutions that had once nurtured them. Of the 5,102 people who worked in higher education before the war, at least 1,112 (or 22 percent)—including 345 women—were killed, detained, or injured, according to a November 2025 UNESCO assessment. Israel’s bombs also obliterated 22 of Gaza’s 38 campuses, while damaging almost all of the remaining ones. The attacks on these institutions of higher education were so unrelenting—and appeared so targeted—that as early as April 2024, experts from the United Nations were warning that they might constitute scholasticide.

“These attacks are not isolated incidents,” more than 20 UN experts said in a statement. “They present a systematic pattern of violence aimed at dismantling the very foundation of Palestinian society.”

Now, amid the slightly lessened horror of the ceasefire, those educators who survived the worst of the war are tasked with figuring out how to rebuild that foundation. And they are tasked with doing so in a landscape in which survival itself remains a struggle.

Death is still a constant threat in Gaza—death from Israel’s bombs as well as from bitter weather, dangerous living conditions, and an enduring health crisis. And rebuilding remains stalled as Israel continues to control the borders into and out of Gaza, restricting the flow of aid and construction materials. Palestinian government statistics show Israel has permitted only 43 percent of the 60,000 aid trucks required to meet Gaza’s actual needs. With so few resources, subsistence, let alone building back Gaza’s treasured education system, is a challenge.

“Higher education in Gaza today fights for survival, not development,” says Abdel Hamid Al-Yaqoubi, an official at Palestine’s Ministry of Higher Education.

Amid so much privation and instability, Abu Layla’s situation is far from unusual; suffering extends across Gaza’s academic community.

When the war escalated, most universities placed staff on unpaid leave, meaning that most received no salaries. With students unable to pay their tuition fees, the universities were unable to pay their faculties and administrators. And many still cannot.

Tawfig Abu Jarad, director of public relations at Gaza University, says he knows of professors who were forced to sell vegetables to provide for their families. “Imagine a university professor accustomed to standing in lecture halls before students, now standing behind a vegetable stand with one of his former students shopping in front of him.”

As the situation has stabilized slightly since the ceasefire, there have been modest attempts at returning to in-person and hybrid education at some institutions. The Ministry of Education and Higher Education has been working with international partners like UNESCO to reorganize education through digital systems like the Virtual Campus, and the ministry held meetings with Gaza university presidents to support education continuity and overcome challenges. UNESCO has also created Temporary Learning Spaces in Khan Younis and Deir Al Balah, where students can access digital resources—many lost their computers during the most extreme phases of the war, and Internet access remains spotty—as well as psychosocial support.

These are crucial efforts to get a generation of students back to college, back to graduate programs. But even amid this progress, the challenges remain overwhelming. “Online education doesn’t meet students’ aspirations, especially in engineering and medical specializations requiring laboratories and in-person instruction,” says Abu Jarad.

Moreover, even these limited efforts reach only a fraction of Gaza’s 88,000 higher-education students—and put only a limited number of professors back to work.

So far, Abu Layla has not been one of them.

As he stands in Al-Yarmuk dump, looking at his certificates earned through two decades of study and effort, he feels a pummeling sense of loss. “I spent my money, sweat, and effort to reach a respectable position in society, not to live next to a trash heap,” he says.

He tries to retain hope, imagining a time when “the beautiful days will return, when I see myself in my rebuilt house, and my children going to their schools.” But he’s not naïve, and he knows that time is still a ways off. He understands the present,

“As long as we live in tents, haven’t returned to our homes, our children’s schools are destroyed, we feel no security or stability, the army occupies Gaza areas, and crossings remain closed,” he says, “the war hasn’t ended.”

Your support makes stories like this possible

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.