Battery Ghosts

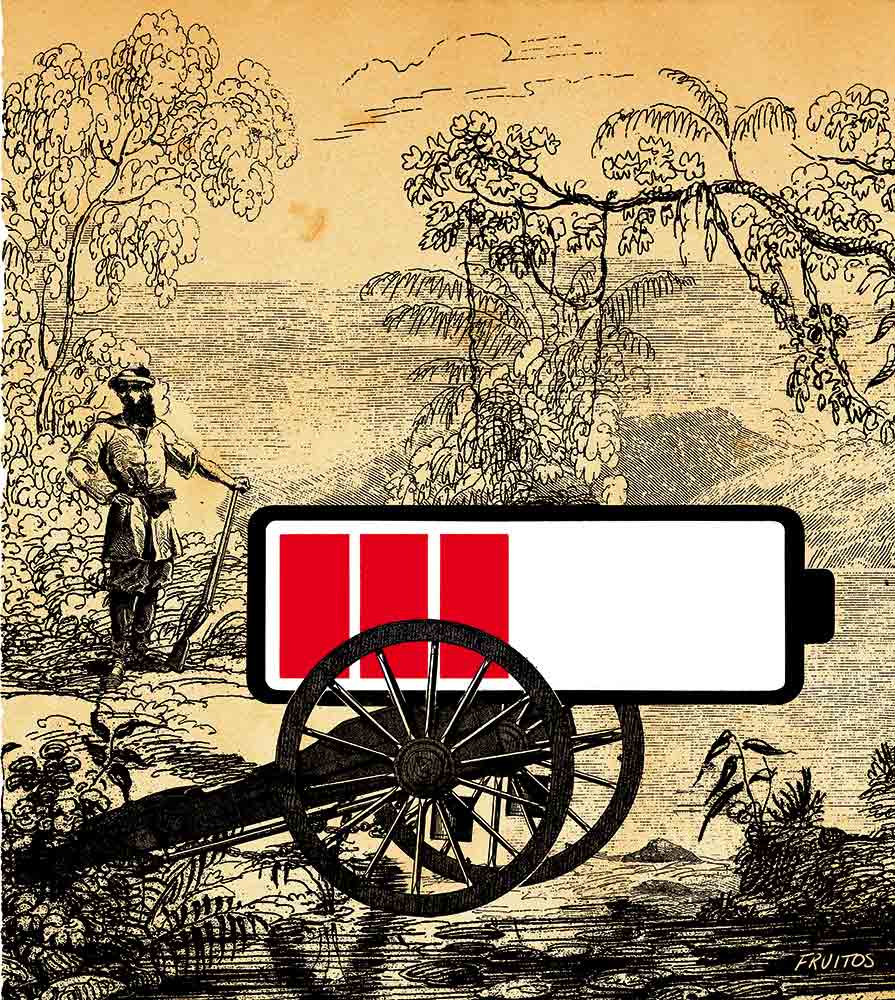

The supply chain for lithium-ion batteries is haunted by the phantoms of colonialism.

The Ghosts of Colonialism Haunt Our Batteries

With its cobalt and lithium mines, Congo is powering a new energy revolution. It contains both the worst horrors of modern metal extraction—and the seeds of a more moral economics.

The 20th century was powered by oil. But in the second decade of the 21st century, we have myriad ways to store power without using fossil fuels. Among these methods, lithium-ion batteries now dominate. Batteries are globalized products—they are built from materials mined in one place, refined in another, assembled somewhere else, and eventually sold in yet another, crisscrossing a multitude of borders in the process. Without globalization, it would be impossible to build them or the computers, phones, and cars that they power.

Understanding these batteries and how they are made is key to understanding how a new form of power is being created, one that is measurable not only in volts but in dollars and strategic influence.

As with oil, battery power can become political power. Lithium-ion batteries have been a major factor in making Elon Musk the richest man in the world. Musk became one of the most influential people in US politics after putting upwards of $288 million into the 2024 election, buying himself a seat at the table of governance—only to flame out a few months into Trump’s second term, partly over disagreements concerning electric-vehicle policy.

At the bottom of this new global supply chain are the workers who toil for pennies to extract the lithium, cobalt, nickel, and other materials without which the batteries that power modern life could not exist. These materials often come from poor countries, where workers are exploited, land rights are not respected, and human rights are violated. So places like Chile, Indonesia, Western Sahara, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo have become the major sources for the metals that power our devices.

This is the story of one of those places: Congo, the site of some of the worst horrors of the modern metal-extraction economy—and where an alternative, and more moral, economics might be identified.

In Congo, perhaps more than in any other country, geology and colonization have been crucial factors in shaping the supply chain that is in use today. Without Congo, which produces 70 percent of the world’s cobalt and has huge lithium reserves as well, the battery revolution would have been much slower.

Over the past six years, I have been investigating the battery conundrum for my new book, The Elements of Power. And I’ve kept returning to the question of Congo: Why is a country so rich in minerals still so poor? How can it be that Congo, the place that people say will power the green, fossil-fuel-free future, remains so defined by its colonial history?

In 1885, Belgium’s King Leopold II colonized Congo. He promised that he would bestow charity upon the country and bring it to “civilization,” but he ended up slaughtering an estimated 10 million people in a drive to extract ivory, rubber, and precious metals.

By the final decade of the 19th century, the invention of the bicycle and the automobile had led to a boom in the demand for rubber. (Synthetic rubber would not be invented until 1909.) Rubber is slow to grow on plantations, but Congo’s forests were full of the vines. Soon, European overseers were press-ganging local men into harvesting rubber. If they refused to work, their wives and children were kidnapped as collateral.

After Leopold colonized Congo, entire villages were enslaved in the quest for rubber, and mutilation and murder were used to enforce loyalty. One particularly haunting image from the period shows a man named Nsala staring at a severed hand and foot on the ground. “He hadn’t made his rubber quota for the day so the Belgian-appointed overseers had cut off his daughter’s hand and foot,” wrote Judy Pollard Smith, the biographer of Lady Alice Seeley Harris, the photographer who took the image. “Her name was Boali. She was five years old. Then they killed her. But they weren’t finished. Then they killed his wife too…. Leopold had not given any thought to the idea that these African children, these men and women, were our fully human brothers, created equally by the same Hand that had created his own lineage of European Royalty.”

The Belgians masterminded the use of corporate structures to carry out this plunder, harnessing not only the greed of their countrymen but that of shareholders in Europe and around the world. As a truly global product, rubber tires were the lithium-ion batteries of their day.

The shareholders’ need for a constant stream of profit is what drove the men who colonized Congo to wipe out its elephants and jungles, enslave its population, and tear open its earth. Companies were created for commerce: There were companies for manufacturing, companies for railroads, companies for mining, and subcompanies for general stores and agricultural products.

Some of the companies founded during this era were the forebears of successful European businesses that still exist today. Umicore, a publicly traded Belgian-French materials technology and recycling company that had a market capitalization of nearly €5 billion in 2026 (and the stated ambition to become a “sustainability champion”), has its roots in Union Minière, one of Leopold’s firms.

A snapshot of Union Minière’s many-tentacled ownership structure in 1960, on the eve of Congo’s independence, shows just what octopuses such corporations had evolved into since their inception in the late 19th century. There was the “General Public,” i.e., the shareholders; Tanganyika Concessions, a British firm that shared an interlocking board with Union Minière; and Société Générale, Belgium’s premier investment bank (which was so powerful at one point that it was called “the uncrowned queen of Belgium”). The structure was designed to be complicated and opaque in order to protect the people who ultimately benefited from the extraction of Congo’s minerals.

After the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, the country’s first democratically elected leader, in 1961, Congo was left in the grip of rulers like Mobutu Sese Seko, who used the country’s immense natural resources as a personal piggy bank and took advantage of the colonial corporate architecture to plunder it. Little has changed since Mobutu fell in 1997: The web of companies that corrupt politicians and businessmen have created in the 21st century in their quest for profits from the extraction of battery metals has an uncanny resemblance to Union Minière’s tentacular structure from the 1960s.

That greed may seem inevitable—as unstoppable as the relentless evolution of cell-phone technology and the profiteering that extends from it.

But could the metals that power the modern age help Congo, rather than condemn it to an endless “resource curse”? Maybe we don’t need to leave Congo’s cobalt in the ground. Maybe, as the green-energy revolution proceeds, Congo’s wealth of resources could actually benefit the country.

Sustainable mining has been demonstrated in plenty of places around the world—in Australia and Tanzania, for instance. And my experience reporting at several mines in southern Congo has shown me how mining can be carried out in a modern manner, with an emphasis on safety, even in the poorest and historically most exploited countries.

A trip to the southern town of Bunkeya in 2022 showed me how Congolese people—and, by extension, people living close to criticalmetals mines around the world—can build better places to live by responsibly developing the resources beneath their feet.

Bunkeya is still governed by a descendant of Msiri, a king whom the Belgians killed in 1891 before invading Congo’s mine-rich south. Remarkably, despite the years of violence and colonialism, Bunkeya has maintained a strong sense of community. And the people of Bunkeya have managed to funnel their portion of the royalties from the nearby Tenke Fungurume Mine (one of the largest copper and cobalt mines in the world) not into some corrupt pockets, but into local agriculture, the construction of infrastructure, and the production of safe drinking water. To be sure, this money is only a small portion of the money made at Tenke Fungurume, but civil-society leaders took me through the numbers and showed me how the local mwami, or traditional king, had ensured that the community would be given its share of the mineral wealth before it could be stolen. According to them, the mwami had accomplished this through a campaign of vigorous advocacy in Kinshasa, Congo’s capital city.

What made it even more remarkable was that, elsewhere, that money was being stolen. In August 2021, the government in Kinshasa began an investigation into Tenke Fungurume to ascertain the true size of the reserves and whether China Molybdenum, or CMOC, a behemoth Chinese mining firm, owed the state money. After Congo suspended the firm’s mining rights in 2022, CMOC agreed to a settlement in April 2023. The firm had to pay $800 million over six years and a minimum of $1.2 billion in dividends over the mine’s operational life and said that it expected the money to “play a stronger role in promoting economic development and job creation.”

Yet a senior US official, who asked that his name not be used because he was not authorized to speak on the record, told me that whatever was being paid was being poorly spent or “put into pockets” and stolen.

Ihad arrived in Bunkeya in July on the anniversary of the mwami’s coronation, one of two yearly celebrations in the territory. I parked outside in the town square, crossed the main street, Boulevard Msiri, and walked through the red-and-white-painted gates of the royal enclosure of Mwenda Bantu Kaneranera Godefroid Munongo Jr., the current mwami. Unusually for Congo, there were few beggars. I heard drumming and gunshots ahead of me as I passed a series of miniature thatched huts—homes for the spirits of each of the mwami’s ancestors.

In a tented courtyard, Munongo sat on a throne wearing white robes as his ceremonial bodyguards, in red tunics, fired ancient muskets into the air. Someone told me that the guards’ guns date back to the colonial era. Traditional chiefs from around the country and African aristocrats—a sultan from Chad, a king from Ghana, and a chief from the Republic of the Congo—lined up to salute the mwami and give him gifts.

Afterward, a foreign agriculture expert explained to me how farming had been improved by the king, how he’d constructed clinics and roads, and that he was even thinking about building a model mine on a hill outside Bunkeya. Here was a community that stood in stark opposition to what was happening in many other places in southern Congo, where big companies and anarchic profit seekers were tearing the social and physical fabric of towns apart—a community that showed that money from cobalt could benefit the poorest in the country.

In a way, Bunkeya has been lucky: There are few mines in the immediate vicinity of the town, which means there are fewer opportunities for the kind of gangsterism that has plagued other parts of southern Congo, where minerals mined in appalling circumstances are trafficked by Congolese and foreign groups. What’s more, the people there have retained a strong sense of their own culture, something that has been stamped out elsewhere in the region.

This is not coincidental. European colonialists sought to deny the history of Africans and encouraged a view of the continent’s populations as people in need of civilizing influences. As the development scholar Kevin C. Dunn has written of Congo, “External actors have frequently attempted to characterize the country as divided, chaotic, and lacking the ability of self-articulation, which in turn has allowed external actors to speak for it.”

Such characterizations allowed the slave trade to flourish along the coast of West Africa and later allowed explorers to claim huge swaths of land for European monarchs. The parallels with today are plain to see, in the condescension with which Westerners speak about Africa and Africans, in the ignorance of African affairs that is demonstrated by US and European powers, and in the treatment of African workers by their Chinese bosses.

Writing for The New York Review of Books in 2018, the journalist Howard W. French noted that one of the key rhetorical moves among supporters of colonialism has been “emphasizing the civilizational virtues that are being shared with less fortunate or explicitly inferior peoples, while minimizing one’s own self-interested objectives and downplaying the violence and dispossession that are usually essential to the subjugation of others.” The deletion of African history was essential to this project, French said, to establish mastery over people in the colonies. Any evidence of ancient civilization was ascribed to external influences. “To accord local agency in such matters would have undermined a long-standing narrative about the inherent inferiority or even subhuman nature of Africans, which was vital in giving Europeans license for their actions.”

What I saw in Bunkeya flies in the face of such license. In some ways, the community always has: Msiri resisted colonial rule there in the 1880s (even though, as scholars like Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja have pointed out, Msiri was not native to the land; he came from central Tanzania). These days, under his distant descendant, Bunkeya is trying once again to break free, resisting the control that has been foisted upon it since Msiri was murdered.

To be sure, most places in southern Congo aren’t like Bunkeya. Most places have been built on the buried dreams of miners and a painful history of exploitation. Sometimes, they have literally been built on human bodies.

On one of my early trips to Congo, I spoke with Charlotte “Maman Ocean” Cime Jinga, a jovial parliamentarian who once served as mayor of the city of Kolwezi. She complained about how corruption was crippling her country and how cavalier the government was with miners’ lives—and their deaths.

The bodies of the artisanal miners who died after a recent cave-in had been unceremoniously dumped, she told me. “There is a mass grave, unmarked,” she said. Officially, 43 people had suffocated or been crushed to death, but she contended that there had been many, many more. To lower the reported death toll, officials had ordered trenches to be dug at the city cemetery, and the bodies of those whose families hadn’t come to claim them were hastily buried.

After my meeting with Maman Ocean, a Congolese colleague and I made some inquiries and found out that such a mass grave does, indeed, exist. It lies in a remote section of the Mwangeji cemetery.

We arrived there in the early afternoon. Mwangeji occupies a giant plot in the middle of town, next to a group of shops that sell wooden coffins.

Marcel, a 19-year-old IT student in a blue suit, was heading for his lunch break. He worked as a gravedigger to make some extra cash, he said. He knew where the unknown miners were buried. There were about 30 of them, he said.

Marcel ushered us into the cemetery, which was quiet and huge and overgrown. Graves were everywhere in the soft soil, and only a few paths wended their way through them.

At the yard’s southern wall, two men were digging. They shouted that I should get out and that I needed authorization to be in the cemetery, even though it was a public site and I was a fully accredited journalist.

Marcel led me away, taking me on a roundabout route through wooden crosses staked into the ground. “Mwangeji is full,” he said. “There is no terre vièrge”—no virgin ground.

The empty areas only appeared empty, because the tall grass and bushes that covered the cemetery were burned at the end of the dry season to free up space for more graves. The wooden crosses would also burn in the flames.

Marcel brought us into an area of thick bush. After a few feet, the foliage thinned out. The mass grave was here, he said, and pointed at a patch of scrub. This is where the bodies had been dumped after the tunnel collapsed.

There were no markings. Reed grass had grown from the soil, and it was long and red and feathery. It shuddered in the breeze.

Thirty bodies lay in the ground beneath our feet. They belonged to men who had been digging out the metals that keep our world powered, and they had been crushed, deep under the earth, in Congo.

To meet the climate goals that will make a dent in global warming, we need to make massive investments in environmentally responsible mining. At the same time, there is still much that needs to be done to focus the world’s attention on the devastation wrought by many forms of mining—to our shared planet, to local lives and livelihoods—and how to mitigate it.

Perhaps what the power-storage sector suffers from the most is a lack of imagination. Many mining companies seem uninterested in the possibilities provided by clean energy. “The big miners haven’t invested in critical-metals projects because they’re too small,” said Brian Menell, the CEO of TechMet, an investment company that specializes in such projects. “One billion dollars barely moves the dial.” But he also thought that few people have woken up to the opportunities offered by critical metals. “There is still a degree of naïveté,” Menell said. The problem, he continued, is that businesspeople and politicians in Europe and the United States don’t look beyond the short term and invest in projects that are important for the future. “You need political will, which you don’t have,” Menell argued. “We should have autoworkers in Detroit demonstrating for more mining; we should have students demanding that their universities invest in clean mining. If investment doesn’t happen, we won’t make our climate-change goals over the next 20 years.”

One way to reconcile the goals of this new energy revolution with the terrible toll it is taking on communities is simple: We should listen to the people who live in the places where we get our minerals. We must listen to them about the pollution in their communities and the exploitation of their laborers and consider their dreams for a healthier, more balanced world.

Such people are commonly excluded from the decisions about how their land is to be used, thanks to the big-stakes financial dealings and the complex, often deadly geopolitical games in the cutthroat competition for resources. But the citizens of wealthy countries cannot simply hope that innovation will save the planet or ignore the horrific suffering that has come to be accepted as the unavoidable price for cleaner cities. To do so risks entrenching a system of cruelty and environmental ruin that will eventually, in ways we are only just beginning to understand, prove as destructive as any hydrocarbon.

Your support makes stories like this possible

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.

More from The Nation

How Heidi Reichinnek Saved Germany’s Left How Heidi Reichinnek Saved Germany’s Left

The co-leader of Die Linke helped rescue the party and make it into a political force. But can she beat back Germany’s ascendant far right?

Gaza Is Still Here Gaza Is Still Here

Despite a “ceasefire,” Israel’s killing has not ended. Neither has the determination of the Palestinian people to survive.

Inside Ukraine’s Underground Maternity Wards Inside Ukraine’s Underground Maternity Wards

Four years after Russia launched its full-scale invasion, Ukrainian health workers are shoring up maternity care to protect the most vulnerable—and preserve Ukrainian id...

1933 Revisited 1933 Revisited

Trump’s ICE agents terrorize American citizens unchecked.

“We Are All Passengers on the Titanic” “We Are All Passengers on the Titanic”

An interview with Grigory Yavlinsky.