The Street That Refuses to Die

The Gaza Street That Refuses to Die

What I saw walking one block in Gaza.

The Colorful Block in 2025.

(Ali Skaik)This piece is part of A Day for Gaza, an initiative in which The Nation has turned over its website exclusively to voices from the Gaza Strip. You can find all of the work in the series here.

I used to know this block, the Colorful Block, by the sound of life.

Children’s laughter spilled from every doorway; men argued playfully over the price of tomatoes; my uncle’s supermarket—bright and packed with goods of every kind—glowed late into the night. The refrigerator hummed, the bulbs buzzed, and the air smelled like oranges and detergent.

That was before everything went dark.

When I came back after the ceasefire, I could barely recognize the street. The neighborhood, once painted in pinks, blues, and yellows to chase away the gloom of the blockade, had turned the color of dust. My uncle’s supermarket was only a blackened frame. Where the candy aisle once stood, a twisted shopping cart now lay half-buried in rubble.

A Day for Gaza

-

A Ceasefire in Name Only

-

The Gaza Street That Refuses to Die

-

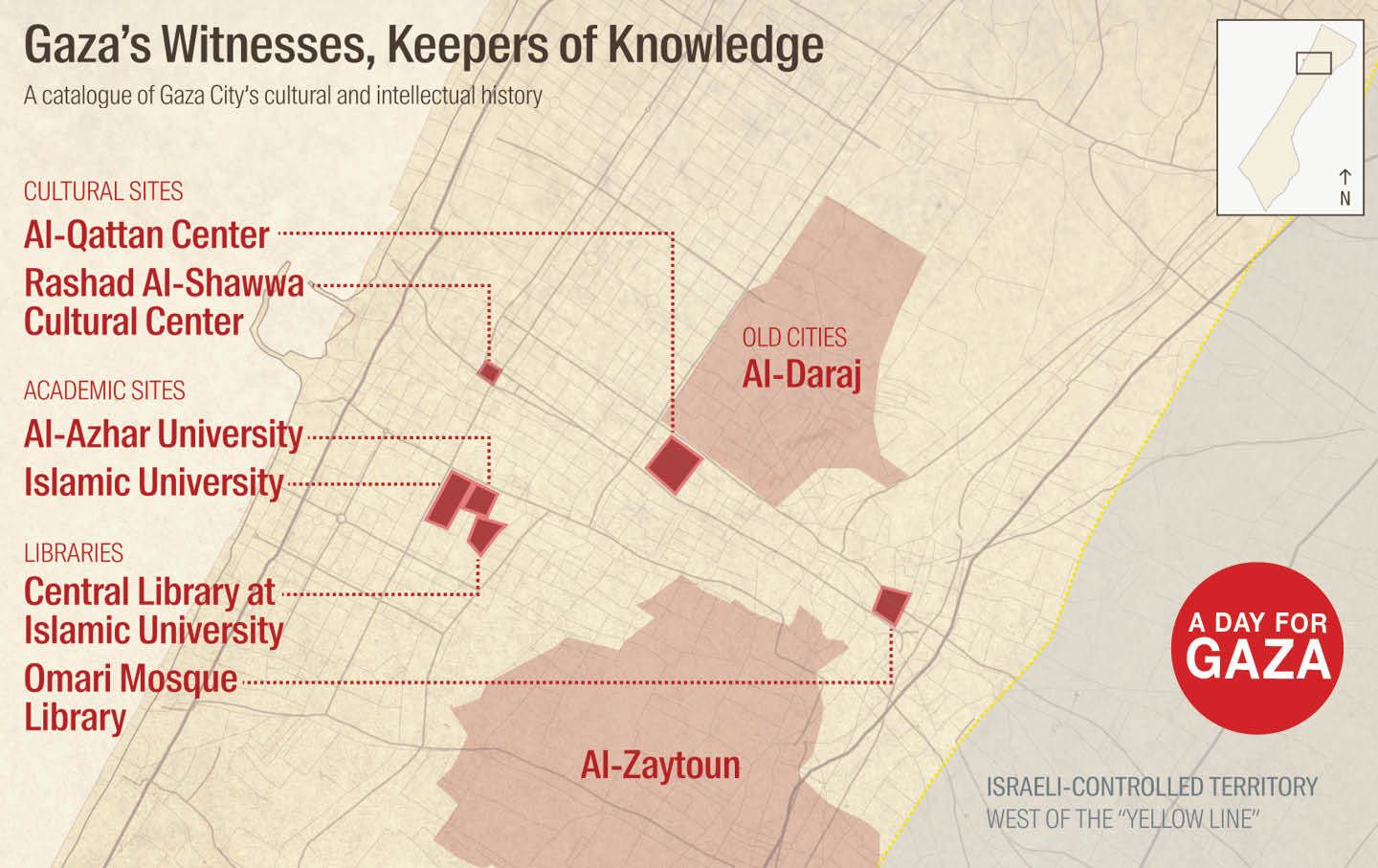

A Catalog of Gaza’s Loss

-

My Sister’s Death Still Echoes Inside Me

-

What Gaza’s Photographers Have Seen

-

How to Survive in a House Without Walls

-

What Edward Said Teaches Us About Gaza

-

What Happens to the Educators When the Schools Have Been Destroyed?

-

At the Doorstep of Tomorrow

-

“We Have Covered Events No Human Can Bear”

People say the war has ended. But walking here, amid roofless rooms and doorways that open onto the sky, you understand: The war has only changed shape. The bombs have mostly stopped falling, but the silence that’s followed is its own kind of violence.

So I decided to try to breach the quiet, to walk this block—house to house, neighbor to neighbor—and ask people how they are living, what they are rebuilding, and what they are still carrying from the genocide that tried to erase us.

“The war of fire ended. The cold war began.”

At the corner, Abdel Rahman Jebril, 33, stood beside what used to be his home, leaning on a stick. His left hand was wrapped in cloth, the fingers stiff.

“The suffering got worse after the ceasefire,” he said quietly. “The war of rockets ended, and the cold war began—a war that burns without weapons.”

His house was hit again and again until it collapsed completely, taking his dreams with it. Now he lives in a cycle of displacement—moving from one borrowed room to another—dragging his children and what little he could salvage.

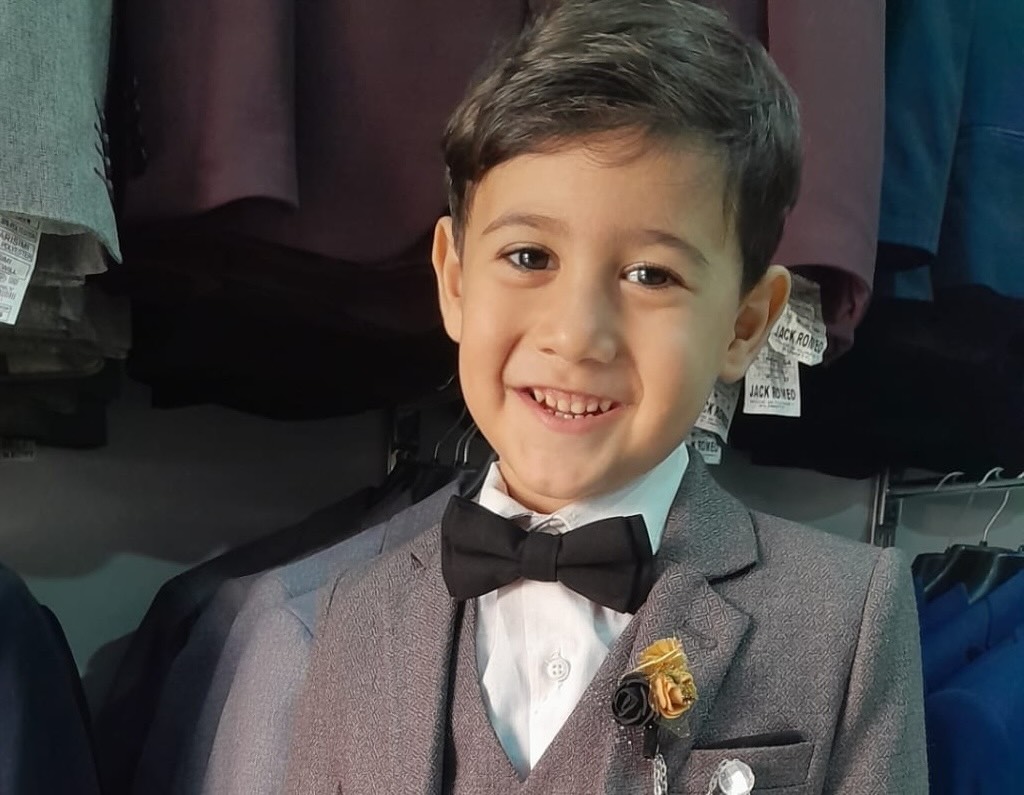

He pointed to a small photograph, edges torn: his son Jude, 6, who wanted to become an engineer, and his daughter Lia, 4, who dreamed of being a doctor. “The genocide took our homes and the futures of our children,” he said.

He looked down at his injured hand. “Sometimes I dream that I wake up and it’s healed—that the house is still standing, that the children are back in school.” He smiled weakly. “But then I wake up for real.”

“Don’t let my children become numbers.”

A little way down the block, in a half-plastered room, sat Nour al-Huda al-Nabih, 33. Stacked neatly beside her was a pile of books, all for her PhD research.

She lives alone now with her husband, Arafat. They survived, but their children, Ahmad and Rasha, did not.

“Rasha was 11,” she told me, her voice steady. “She was strong, always looking after her brother. In her little will, she wrote, ‘Please don’t yell at Ahmad.’”

Her eyes softened. “Ahmad was so kind. He used to share his snacks with everyone.”

After the ceasefire, the first thing she did was visit their graves. Then she returned to her doctoral studies, researching trauma in Gaza. “When I help children smile,” she said, “I feel my own children smiling somewhere, too.”

She still finds herself in the market, reaching for the same snacks Ahmad and Rasha used to love. “Sometimes I whisper, ‘If they were here, I’d buy this for them.’”

She gestured around her unfinished room. “I feel like a queen,” she said, “because I have walls. Many people don’t even have that.”

Then she looked straight at me. “My message to the world: ‘Don’t let my children become numbers. Remember their names. Gaza has always stood for the world; now the world must stand for Gaza.’”

“They want a land without people”

On the sidewalk sat Mohammad Mansour, 74, wrapped in a wool scarf despite the heat.

“Since the Balfour Declaration in 1917,” he began, “we’ve been living this occupation. They want a land without people. This genocide is their way of finishing the project.”

He listed what was destroyed: homes, schools, mosques. “They even turned it into a war on faith,” he said.

Before the war, $30 could fill his pantry. During the genocide, one kilo of onions cost $100. “Now prices go up and down like bombs,” he said.

He spoke of two people he’ll never forget: young Aref Abu Laban, who was killed while helping his mother pick lemons, and his old friend Mohammad al-Saidi, who had dreamed up the Colorful Block project that once made these walls bright. “He believed color could defeat despair,” Mansour said. “Now the walls are gray again, but the dream is still alive in my heart.”

“We live as if the war never stopped.”

I met Dunya Ashour, 19, when she was taking some photos of the destruction of the New Ajjami Mosque.

“I don’t feel the ceasefire,” she told me. “At night I still wake up to explosions two kilometers away, in the yellow zones. I can smell the gunpowder in the air.”

She lost her favorite teacher, Arij al-Maydana, as well as her grandfather, Jameel. “I carry their loss every day,” she said, “but I tell myself they’re in a better place.”

Against all odds, she finished her high school exams after two years of delay. “I studied under bombardment,” she said proudly. “I got 92.4 percent.”

Her family is displaced; their house is gone. “We might leave Gaza if the Rafah border opens,” she said. “But I want to come back one day as Dr. Dunya.” She will return, she often says, as the dentist who rebuilt her own smile.

She looked around the ruins. “The genocide taught me not to grieve over small things,” she said. “Every morning I wake up alive is a victory.”

“No place is sacred anymore.”

I talked to Montaser Tarazi, 35, in the Latin monastery church located next to the Colorful Block. Tarazi is a Christian. “After the ceasefire, things became slightly less dangerous,” he said. “I can walk to the market again without fearing I’ll die halfway. But the loss… ” He paused. “The loss walks with us.”

His best friend, Dr. Suliman Tarazi, a dentist, was killed while taking shelter in the Orthodox Church. “That strike broke something in all of us,” he said. “If even the church can be bombed, nowhere is sacred.” Montaser’s house was destroyed. For three weeks, he and his family cleared rubble by hand. “We rebuild with our fingers,” he explained. But without equipment or cement, they gave up. It was like trying to plant a tree in ashes.

Yet he still believes in change. “If a unity government forms, if aid finally enters without limits, maybe Gaza can breathe again,” he said. “After more than 68,000 martyrs, something in us must change forever.”

“Life, even like this, is a gift.”

At the entrance to the block stood my maternal uncle Hassan Skaik, 29, in front of what used to be his supermarket—the same one where I once worked. “I feel both good and bad,” he told me. “Good, because the blood stopped flowing. Bad, because everything else stopped too.”

His supermarket is destroyed: the refrigerators crushed, the shelves twisted. “Before, it was full of lights and laughter,” he said. “Now I only hear my own echo.”

He lost nine friends from the Al Saqqa family in one air strike. “It still feels unreal,” he said softly.

At night, he dreams of running from fire belts. “Every night,” he said, “the same nightmare.” But he’s learning to be grateful for survival. “We’ve started from zero before,” he said. “We’ll do it again…life, even like this, is a gift.”

“Finding water is our new war.”

At the far end of the street, Mahmoud Haddad, 38, stood by a cracked water tank, his shirt soaked from work.

“The only thing that changed after the ceasefire,” he said, “is that the bombs are quieter.”

He and his neighbors cleared debris from a collapsed saltwater well, trying to make it usable again. “The municipality doesn’t work,” he said, “so we do it ourselves.”

They ration water by the liter. “Drinking water costs $2 for 20 liters, if you find it,” he said. “Sometimes we share one liter for two days.”

His friend and coworker Diya Hammam was killed in the war. “He made everyone laugh,” Haddad said. “Now the whole street is silent.”

He believes the only real solution begins with education. “If the schools reopen, Gaza will start breathing again,” he said. “Without education, we’re just surviving.”

“The crisis is in my heart.”

Khaled Al Saqqa, 28, is one of the few survivors of his family. His mother and seven siblings were killed.

“I’m the dead one,” he said. “They’re the ones alive.”

Every morning he visits the rubble of his house. “I touch the walls,” he said. “I talk to them. I tell them I’m still here.”

He recently married. He is working on setting up a tent over the rubble of his home to live in with his wife, Dareen. “Rebuilding isn’t about cement,” he said. “It’s about learning to live again.”

He looked at me with tired eyes. “The crisis isn’t in the ruins,” he said. “It’s in my heart. But every breath I take here is for them.”

“Only faith remains.”

Beside a torn canvas tent, I found Jamal al-Aklouk, 64, sitting on a plastic chair.

“I retired three years ago,” he said. “Bought my dream home. Thought I’d die in peace there.” The home is gone now; he lives in this tent.

The destruction of Gaza’s mosques wounded him deeply. “I prayed near the rubble of the Great Omari Mosque,” he said. “Right then, I got a call—my grandson Ahmad was martyred. He was 7.”

He still carries the pain in his legs from running 17 hours from tanks. “I can’t sleep from the ache,” he said, “but I remind myself—if I can feel it, I’m still alive.”

He gazed at the sunset. “Everything passes,” he said. “Only faith remains.”

“From prisoner to builder.”

At the end of the lane stood Saeeh Al Haddad, hammering nails into a wooden frame. He was in Israeli prisons for 19 years and was released in the prisoner exchange deal in January 2025.

“In prison, I lost my freedom,” he said. “But at least there, I was still alive. Out here, freedom feels like rubble.”

He refused to flee during the war. “When the genocide ended, a new battle began—the fight to adapt.” He lost his brother, Mohammed, his brother’s wife, and his sister’s family. “I carry them with me every day,” he said.

Now he’s rebuilding what he can and planning his wedding. “One day,” he said, “Gaza will be rebuilt more beautifully than before. People will say, “Is this the same Gaza that was turned to dust?”

He smiled, eyes glistening. “The world needs Gaza,” he said, “to learn how people can build hope from nothing.”

When night falls in the Zeitoun neighborhood, the street glows again—not with electricity but with firelight. Families cook lentils on makeshift stoves; children chase shadows with tin cans for toys. The scent of smoke mixes with sea air and memory.

I stop at the ruins of the supermarket. The tiles are cracked, but if I close my eyes, I can still hear my uncle calling, “Cold slash! Come before it’s gone!”

He was right. Everything is gone.

And yet, somehow, everyone is still here.

Each neighbor carries a piece of Gaza’s story—a mosaic of grief, faith, and stubborn hope. They are rebuilding not just homes, but the meaning of life itself.

In this neighborhood, the war may have paused, but it has not ended. Still, the people refuse to disappear.

Before I leave, I see a boy running through the rubble, barefoot, laughing, a kite made from a plastic aid bag fluttering behind him. It catches the last light of the setting sun.

For a second, it feels like color has returned.

The street is broken, silent, waiting.

But it refuses to die.

Your support makes stories like this possible

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.