A Living Archive of Peter Hujar

The director Ira Sachs’s transforms an intimate interview with the photographer into a film about friendship, routine, and why we make art at all.

There is nowhere to hide in a Peter Hujar portrait—not even in the shadows, which the photographer handled with a singular, sensuous grace. He could reach into a subject and find a point of surrender, translating quietude and startling candor into a picture’s tonal contrasts. From the 1950s until his death in 1987, Hujar documented the creative lodestars of downtown New York, many of whom were his friends, lovers, or sometimes both. He photographed the likes of Susan Sontag and John Waters stretched in repose, or the Warholian legend Candy Darling, encircled by flowers and solemn chiaroscuro on her deathbed. He often photographed himself, too, but the rarest shots of Hujar are those taken by others, candid glimpses that divulge some secret relation. One of these is a Polaroid of Hujar from the 1970s, nestled on a couch with his longtime friend, the writer Linda Rosenkrantz, their heads tilted and conspiratorial in the piercing flash.

This image of friendship seems to anchor Ira Sachs’s new film Peter Hujar’s Day, adapted from the transcript of a long-lost conversation between Hujar and Rosenkrantz that took place on December 19, 1974, condensed and published by Magic Hour Press in 2021. Originally part of a broader project to find out “how people fill their days,” Rosenkrantz had asked Hujar to set down all the ins and outs of any 24 hours in his life—in this case, the 18th of December. Recorded in her apartment the following day, Hujar’s account is filled with the names of cultural heavyweights, alongside a whole lot of nothing that language spins into something. There’s a morning phone call from Sontag, another from Fran Lebowitz, and then the day’s central event: a portrait session with Allen Ginsberg for The New York Times. Between these episodes are midmorning naps and sprouted-wheat sandwiches, fleeting erotic fantasies and a freelance artist’s slapdash accounting of payments owed.

In Sachs’s film, December 18 is a phantom we hear about but never see. What we experience instead is that next day in Rosenkrantz’s apartment, as Hujar (Ben Whishaw) fills it with all the textures and trifles of the previous day. From late morning until early evening, he and Rosenkrantz (Rebecca Hall) drift from room to room in the stretch and slant of the changing light. By that winter, the two friends had known each other for almost 20 years. They’d first met in 1956, when Hujar was dating Rosenkrantz’s friend, the painter Joseph Raffael, though their camaraderie would outlast all bar one of Hujar’s lovers. But if the rolling cadence of Hujar’s idiosyncratic voice is front and center in the original transcript, Sachs widens the aperture and brings Rosenkrantz into focus as well, transforming a day of largely solitary recall into a gentle, somatic duet.

Shot on 16-millimeter film, Peter Hujar’s Day conjures a kind of archival realism through its documentary source material and nostalgic grain, as though we’re watching fragments of footage unearthed from a private, dusty trove. The film never introduces the depth of Rosenkrantz and Hujar’s shared history, but we do not need verbal exposition to understand what they mean to each other. Sachs has found a way to foreground what cannot be seen on the written page: the attentive look of the interlocutor while she listens, rapt. The result is a film that centers what Gertrude Stein once wrote of life with her beloved Alice B. Toklas (after whom Hujar and Raffael named one of their cats): “Some one who was loving was almost always listening.”

The Hujar project was partly a way for Sachs to continue working with Whishaw, who first appeared in his previous feature, Passages (2023). There, he played the unwilling third in a queer menage à trois, caught in a maelstrom of desire unleashed by his impulsive husband. Whishaw has the starring role in Peter Hujar’s Day, but there’s no combustive drama with which to flaunt his command of character and pathos. The actor is keyed instead into those minor affects of the everyday, expressions that become arresting despite—or because of—their quietude. Boredom or nervous distraction flits across his face; listlessness drives him to light one cigarette, then another. Whishaw slips into the character with remarkable ease despite his physical incongruities—five-foot-nine to the photographer’s lofty six-foot-three—though it’s perhaps unsurprising that the actor who once voiced Paddington could embody Hujar, a man whose presence was so calming that Nan Goldin once called him “human Valium.”

Set entirely in Rosenkrantz’s apartment—though Sachs has swapped her former Yorkville neighborhood for Westbeth, the artists’ housing complex in the West Village—the central conceit of Peter Hujar’s Day is also its main challenge: This is a two-person chamber drama in which the chamber must supply the drama. But Sachs and cinematographer Alex Ashe understand how a certain shadow or ray of sun can coax out a room’s latent moods. There is the initial lucidity of crisp, midmorning light, when Hujar and Rosenkrantz begin their conversation in the living room, facing each other like proper subject and journalist, a microphone on the coffee table between them. But their postures loosen up as the day unfurls; when the two move into her bedroom, the warm glow of a bedside lamp evokes a scene of late-night confession between close friends. Confined to invitingly furnished interiors, they’re never forced out of their casual languor, slumping or lolling on a sofa and then a mattress, quipping and jesting while supine. Across every frame, their bodies remind us that intimacy is a kind of collaboration, a mutual exercise in physical and emotional closeness.

Sachs’s biggest intervention is in the way he builds action—if smoking a cigarette while shelling pistachios or perusing a friend’s bookshelves could be called action—into Rosenkrantz’s transcript, which is nothing but dialogue. The dramaturgy of a mundane task lures us into new reaches of the apartment, creating occasions for the camera to rove. We glimpse a bright kitchen with a boxy TV set when Rosenkrantz prepares a pot of tea, then discover a dining area when she carries out the refreshments. Noisy construction is reason enough to enter yet another room as Hujar rises to close an open window, quelling the unbearable percussion of a jackhammer outside. Even their one-off jaunt to the rooftop is tied to arbitrary action, ostensibly to go outside while Hujar rips a cigarette in gold-rimmed aviators—until we remember he’s been lighting up indoors and with abandon since Rosenkrantz first hit “record.”

But where, exactly, is the tape recorder now? No stray objects are visible up here, just two friends wedged into a rooftop corner and surrounded by the city’s vertical strata. As a framing device, the recorder anchors the film, reminding us of the impetus behind this entire exchange: as documentary material for Rosenkrantz. Early on, Sachs often cuts to close-ups of the machine as it runs, smooth and steady, its presence heightening our experience of voyeuristic intrusion. But as the pair lounge and drift, the tape recorder’s placements grow less practical, nestled in the fuzzy tendrils of a shaggy white throw blanket like something forgotten in the grass, or set impossibly far across a room. When it disappears entirely in the handful of outdoor interludes, we are reminded that, in the end, this exchange is being performed for us.

Occasionally, Sachs punctures the film’s fierce verisimilitude with brief but insistent moments of theatricality. There is the opening shot of a clapboard as Whishaw steps into a lift, and the various jump cuts that signal deliberate elisions in the script. In the latter half, there are close-ups of Whishaw and Hall as they rupture the fourth wall with slow, piercing looks, Mozart’s Requiem in D Minor swelling in the background. These tableaux vivants play like dramatic allusions to Hujar’s intimate photographs, a live performance of the archive.

In some ways, Peter Hujar’s Day might appeal to a broader curiosity about the rituals that scaffold the daily lives of lauded artists and writers, as though the stuff of creative brilliance could be grasped and transmuted into an imitable method. The diaristic impulse behind Rosenkrantz’s initial project with Hujar—and her earlier novel-in-dialogue, Talk—was shared by that decade’s other experimental artists. In 1971, the poet Bernadette Mayer journaled and shot through a roll of 35-millimeter film every day for the entire month of July, collected as the durational project Memory. The avant-garde filmmaker Jonas Mekas combed through years of 16-millimeter footage that he shot on the Lower East Side to assemble diary films, like Walden (1968) and Lost, Lost, Lost (1976), laden with the weight and lyricism of personal memory. As with these works, there is neither routine nor didactic value in Hujar’s account of December 18, but something ineffable is brought out by processing the banalities of an unremarkable winter’s day.

Hujar was attuned to the revelations of process in more ways than one. Among all the prints and papers in his official archives at the Morgan Library, there are over 5,700 black-and-white contact sheets, each documenting the artist’s particular relationship with the printing of his photographs. These contact sheets index the lifespan of a Hujar picture from negative to final print: every exposure test and chemical bath, every manual dodge and burn in the darkroom’s red light. For Hujar, the act of printing itself was another moment of possible transformation, so personal and central to his practice that he never let anyone else make prints of his work.

But in 1987, Hujar’s AIDS diagnosis permanently foreclosed his return to the darkroom. He bestowed the task to Gary Schneider, a former subject and pupil who remains Hujar’s posthumous printer, decades after his passing. Hujar taught him to “make one print at a time,” Schneider writes in a book about his practice, so that “the process of exploration can continue. This keeps the prints alive.” There is a similar exploratory impulse in Sachs’s film: the belief that there is something to be found in the transcript of a long-forgotten conversation, staged half a century later. What emerges is not an elegy, despite the incoming decade of crisis and unbearable loss, but a glimpse of the love between two old friends and the recognition that keeps their world alive.

Support independent journalism that does not fall in line

Even before February 28, the reasons for Donald Trump’s imploding approval rating were abundantly clear: untrammeled corruption and personal enrichment to the tune of billions of dollars during an affordability crisis, a foreign policy guided only by his own derelict sense of morality, and the deployment of a murderous campaign of occupation, detention, and deportation on American streets.

Now an undeclared, unauthorized, unpopular, and unconstitutional war of aggression against Iran has spread like wildfire through the region and into Europe. A new “forever war”—with an ever-increasing likelihood of American troops on the ground—may very well be upon us.

As we’ve seen over and over, this administration uses lies, misdirection, and attempts to flood the zone to justify its abuses of power at home and abroad. Just as Trump, Marco Rubio, and Pete Hegseth offer erratic and contradictory rationales for the attacks on Iran, the administration is also spreading the lie that the upcoming midterm elections are under threat from noncitizens on voter rolls. When these lies go unchecked, they become the basis for further authoritarian encroachment and war.

In these dark times, independent journalism is uniquely able to uncover the falsehoods that threaten our republic—and civilians around the world—and shine a bright light on the truth.

The Nation’s experienced team of writers, editors, and fact-checkers understands the scale of what we’re up against and the urgency with which we have to act. That’s why we’re publishing critical reporting and analysis of the war on Iran, ICE violence at home, new forms of voter suppression emerging in the courts, and much more.

But this journalism is possible only with your support.

This March, The Nation needs to raise $50,000 to ensure that we have the resources for reporting and analysis that sets the record straight and empowers people of conscience to organize. Will you donate today?

More from The Nation

The Fictitious Capital of HBO’s Industry The Fictitious Capital of HBO’s "Industry"

In the show’s fourth season, everyone has a story to sell and very few are true.

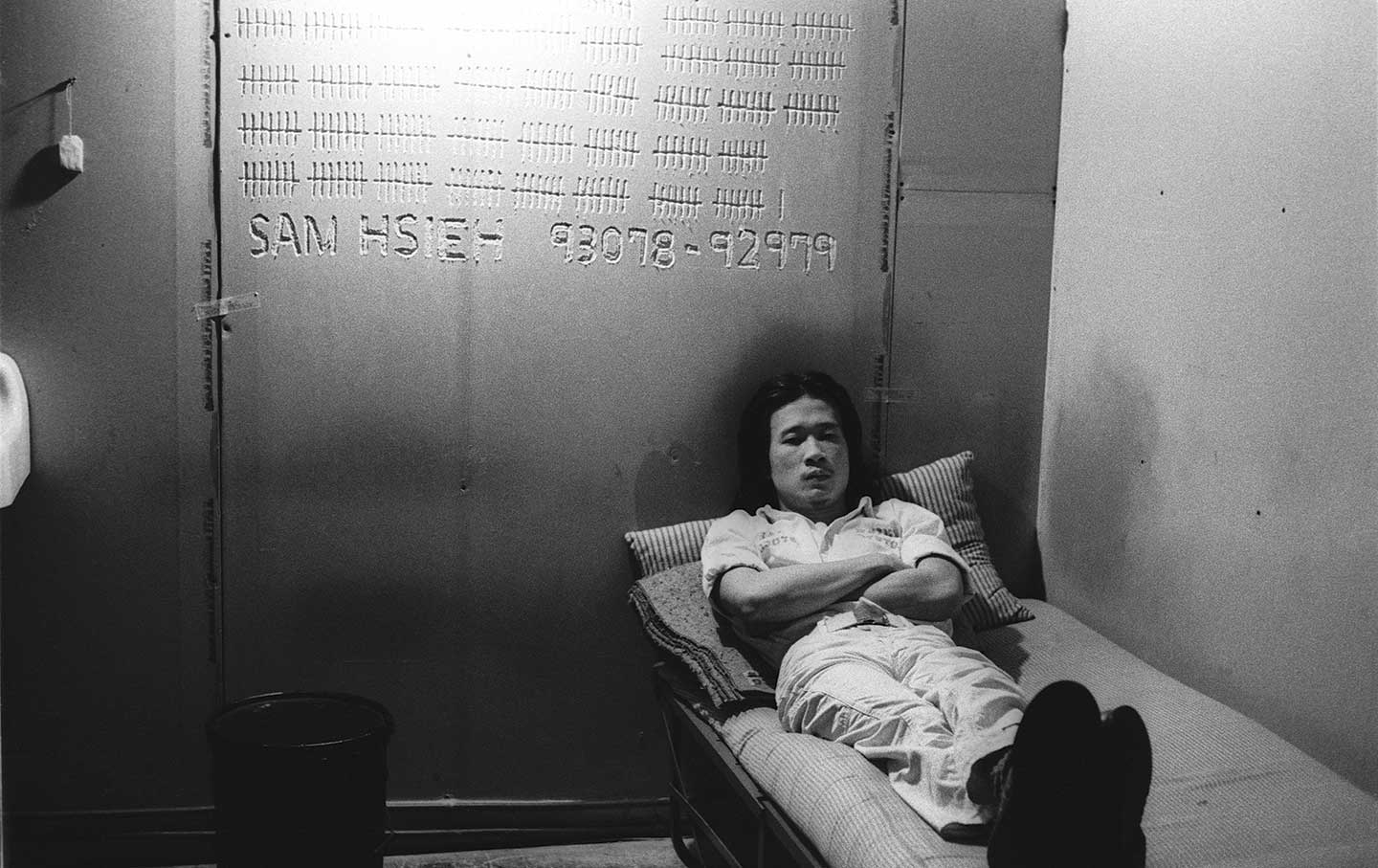

Tehching Hsieh—an “Artist Without Art” Tehching Hsieh—an “Artist Without Art”

In his performances, he questioned whether or not an artwork needed to supply a specific meaning in order to generate a feeling.

George Packer’s Liberal Imagination George Packer’s Liberal Imagination

What happens when liberalism’s crisis is made into a fable?