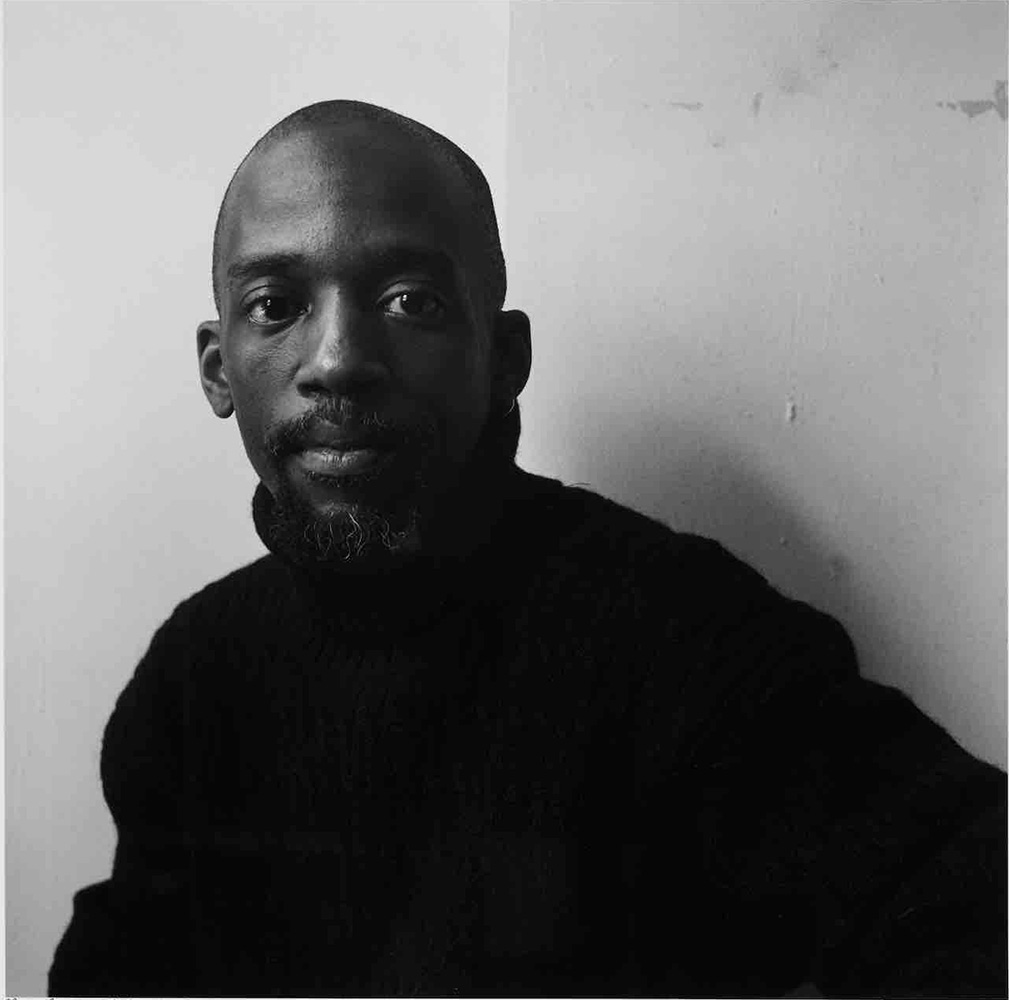

Essex Hemphill’s Poetry of Belonging

He was an artist and activist who found in his verse a tool for both community and agitprop.

It’s never been easy to survive as an American poet, but the late 20th century was especially tough. The popular relevance of the medium waned and the cost of living rose; government funding for the arts imploded. Poets were bedeviled by circumstance, with fewer chances for stability than their peers in newspapers, magazines, and other facets of mainstream publishing.

Books in review

Love Is a Dangerous Word: The Selected Poems of Essex Hemphill

Buy this bookAnd there was a more widespread crisis engulfing America (and the world): AIDS, which killed so many, erasing wide swaths of communities and their mechanisms for remembering themselves. Marginality, mass death—these are just a few of the reasons why the oeuvre of Essex Hemphill, who died of the virus in 1995, has only been available, until now, in snatches.

Hemphill does remain quite well-known in certain circles—even if his one full-length collection, the pathbreaking Ceremonies (1992), has long been out of print. He was a noted activist, famous for the compassion he brought to the then-nascent concept of intersectionality, by sounding the alarm of homophobia in the Black community and racism in the gay community. The anthology he edited alongside the late Joseph Beam, Brother to Brother: New Writings of Black Gay Men (1991), assembled Black gay writers and artistic figures in order to imagine a more sanguine future for a population that, already beset by oppression on multiple fronts, was then besieged by a pandemic. The book’s scope, its readiness to address art and politics in the same breath, echoed the 1960s and ’70s Black Arts movement and the Harlem Renaissance; both had queer elements that were often hushed up, if retrospectively evident in the work of writers as varied as Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, and Nikki Giovanni. This suppressed history suggested, to Hemphill and Beam, a hidden latticework in the frame of Black American culture.

Hemphill was one of the major voices in an out-and-proud polylogue. He wrote about the “fragile coexistence” of his cross-section of identity in an introduction to Brother to Brother, though his determination seemed anything but delicate: “Ours should be a vision willing to exceed all that attempts to confine and intimidate us.” For Hemphill, this threat of confinement extended not only to the mutual pigeonholing of the Black and gay communities but to formal concerns—for example, the primacy of the written over the spoken. He formed a music-poetry duo, Cinque, which put on highly rehearsed group performances that bent his verse toward both rap music and the call-and-response traditions that course through Black musical history. The oral element of this work has meant that Hemphill’s poems have been more available on celluloid than in books—his words anchored films like Isaac Julien’s revisionist historical fantasy Looking for Langston (1989) and Marlon Riggs’s Tongues Untied (1989). The latter also features Hemphill as a performer, spinning his poem “Now We Think” into a spectacular, polyphonic verbal performance. Reading it, he seems to stare into the viewer’s soul, his single hoop earring dangling obstinately in the corner of the frame.

Hemphill dragged poetry into an agit-prop, audiovisual age that could seem allergic to the genre’s unhurried charms. Yet popularity was hardly a careerist tool—it was, instead, a political one. Hemphill knew precisely what his public profile afforded him. To be just a poet would have been an inadequate reaction to his times; like Amiri Baraka and June Jordan—Black poets and public intellectuals of the generation before him—he saw himself in the dual role of activist and artist. The extra-poetic dimensions of his practice have meant that the poems themselves are too often viewed as addendums to his politics, or as lyrical threads that he wove into the more commercial forms of cinema and performance—and more rarely as literature alone.

Love Is a Dangerous Word: Selected Poems, a collection of Hemphill’s work chosen by the critic and professor Robert F. Reid-Pharr and the poet John Keene, is an urgent addition to a formidable if spottily recorded legacy. Unlike Ceremonies, which merged political and personal essays, poems, and stories, this new release focuses on Hemphill’s exquisite verse, allowing us to admire him as a stylist while also providing a reminder of why he found it necessary to bring these lingual gifts to bear on politics. Or Hemphill’s weapon, no matter how he reached an audience, was writing.

Reid-Pharr and Keene organize Love Is a Dangerous Word by the various volumes in which these poems initially appeared, though not chronologically. This arc leads readers from the best-known works to those that have been secreted away in archives. First, there’s every poem that Hemphill included in Ceremonies; then selections from his three chapbooks, Plum (1983), Conditions (1986), and Earth Life (1988); after that, the uncollected poems, some published in magazines, others in a seldom-seen graduate-school project, The Essex Hemphill Reader, undertaken by the academic Dadland Maye. The editors don’t provide dates of composition or other background information alongside the inclusions, though, allowing each movement of Hemphill’s career to flow into the next—they want us to experience his poems as a ceaseless wash of verve and conviction, rather than couching them in a particular period or framing them with scholarly debate.

Consequently, Hemphill’s style takes center stage: His knack for repeating a stanza and varying it just enough that it breaks your heart when it comes around again (for example, his chorus of “I am an oversexed well-hung / Black Queen” in the long poem “Heavy Breathing,” and how in this refrain’s last appearance, he concludes with a reference to the slogan of ACT UP: “Influenced by phrases / like Silence=Death”); his insistent, often implicating employment of the first person; his use of enjambment, and how this leads short, emotionally concentrated lines to barrel into one another. Here, for example, is his poem “O Tell Me, Brutus”:

O tell me, Brutus

with corpses decomposing

in the river,

loved ones keeping fevers

quiet in city hospitals,

the backrooms, locked and chained,

the police with new power to seize

and search our hearts, our kisses,

our mutual consents around midnight.O tell me, Brutus

What are we to do

With all this leather

All these whips and chains?

Hemphill toys with the treachery of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, presenting the play’s themes of betrayal as high camp, as he turns the very concept of blame on its head: Those habitués of the shuttered backroom bars he mentions are neither victims nor culprits but willing lovers. The poem is so powerful because of its momentum, because it can be read in a single breath, because it packs in notes of both primness and defiance. The density of his poems’ allusions are surprising, too: This writing merges cultural worlds, yet its overwhelming impression is that of clear-eyed oration, not heady exploration.

Crossing boundaries, for Hemphill, meant that his message had to be unencumbered by difficulty. If his work could be hard to process emotionally, its form and scansion were hardly ever an impediment to meaning. His rhythms are infectious, like those of the pop songs he coyly references as though to decorate his texts with the sensory experience of a gay bar. His work often has a practiced beat (read aloud, its 4/4 time signature is audible), which gives his free verse a structure that he loved to torque—either through twisting cadences or by luxuriating in a lilting meter. Take the bracing “Sultan”:

He penetrated every chamber,

storing himself inside of me,

in every cell and follicle,

in every pimple and artery,

he established residence

to be recalled in my dreams

or summoned by my hand.

In a different vein, there’s “P.O. Box,” an anti-poem of stats and figures. Here the numbers, rattled off in a list, labor against Hemphill’s rhythms, as though to channel closed-off men who can’t understand their own beauty—who see themselves and their partners as activities and appendages to be offered up with unsparing efficiency. The piece presents sex as cut-and-dried, a salacious CV that prefigures our age of hookup apps:

32 bearded.

37, f/a, g/k passive, 165 lbs.

49 a muscular bottom.

25 uninhibited.

52 prefers french tongues, whippings, hand

beatings.

35 has toys for boys.

22 is uncut and new to the scene

29 needs a little bowl to put some sugar in.

prefer black bottoms, big balls, buns well done.

no s&m, fats, fems, no fist-fucking.

tired of baths bars bushes bookstores beating off.

must be very horny, very hung, very young.

wish to quietly court, date adonis, lick leather.

Dial 338 late at night you can call I’m a number.

Hemphill’s work is unabashedly erotic and also relentless in its solicitude. He saw prejudice—of both race and class—as baked into a gay male sexual sphere that reduced people to physical acts and attractive features, so often stripping sex of its intimacy in the process. He stirred up controversy for decrying the fetish-oriented photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe—an artist who depicted Black models in one of his most notorious works, Black Book (1986), by cropping their heads and focusing on their genitalia, their bent backs and limbs. Hemphill’s broadside pissed off a lot of white queens, in part because Mapplethrope had already died of AIDS when Hemphill mounted his critique. The timing was unfortunate, a reflection of an era that begged for social change even as the devastation of its ongoing pandemic cut every which way. Yet Hemphill would not allow the white photographer to become a sacred cow in his posthumous reception when so many of his Black contemporaries were dying in obscurity. His criticism of Mapplethorpe helped bring new questions of representation to the fore of intersectional discourse. Hemphill tried to redefine sexuality as something to prize in oneself and to give to others as a gift, proffered in good faith. One of his better-known poems, “Rights and Permissions,” begins:

Sometimes I hold

my warm seed

up to my mouth

very close

To my parched lips

and whisper

“I’m sorry,”

before I turn my hand

over the toilet

and listen to the seed

splash into the water.

Ejaculate returns at the end of the poem: “Sometimes I hold / my warm seed / up to my mouth / and kiss it.” “Rights and Permissions” treats sex like a revelation of pleasure and connection, encouraging us not to reduce it to some sterile routine imbued with either implied self-disgust or rote disinterest. This poem about semen has a jarring sensitivity, turning the act of orgasm into something sacrosanct.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In Hemphill’s poetry, affection was always equal-opportunity. He pined for a meaningful hookup the same way he might wish for a better relationship with a father or sibling—an earnestness that could be saccharine in the hands of a less capable poet, though Hemphill was able to convey biological families as weights in an earnest if complicated balancing act. “So when I am with you, my friend,” Hemphill asked in the poem “Fixin’ Things,” “and we open our hearts to one another, / I wonder why I have never / Done this with my own blood brother?” He dreamed of a reality in which openness and receptivity could shave down decades of emotional callouses. The vehemence of his voice—as if he’s upset or infatuated but doing his best to keep everything in equilibrium—is one of its most enduring qualities.

What Hemphill’s poetry achieved, which his contemporaries and forebears continued to wrestle with, was how to make ardent pleas that entreated readers—Black, gay, and otherwise—to consider themselves in the context of a community, while insisting upon the need to make art that was aesthetically gratifying. He did this by harnessing a forward-thinking, first-person voice even if his work wasn’t confessional, no matter how much it felt as though it was. Hemphill’s liberationist spirit was enmeshed in the experience of “I” as a speaker, in the excitement of recognizing the intricacies of the self amid the cacophony and coldness of modernity. Yet his “I” was most often fictionalized, assuming the role of a character. Or else he exploded it in order to contain whole provinces of experience—to address his hometown of Washington, DC, for example, or Black queer allies worldwide. To be a poet in the late 20th century was harrowing—for Hemphill as for anyone—yet from the perspective of reaching people, he succeeded more than just about everyone.

Hemphill siphoned the core of his epoch’s difficulties and shaped them into a theme, one of the central motifs of his work: the necessity of communication. The inability to communicate is, in his view, the greatest barrier to collective possibility. “How can we share the future / if we can’t be instructed by our grief?” he asks during a particularly haunting moment in Love Is a Dangerous Word. To learn from grief is to comprehend that bereavement can help people appreciate the tenuousness of life—that we can be made more understanding of our mutual humanity. Hemphill’s words, not just his death, are a guide. And meanwhile, the world still waits for us to sort out how to share it.

Support independent journalism that does not fall in line

Even before February 28, the reasons for Donald Trump’s imploding approval rating were abundantly clear: untrammeled corruption and personal enrichment to the tune of billions of dollars during an affordability crisis, a foreign policy guided only by his own derelict sense of morality, and the deployment of a murderous campaign of occupation, detention, and deportation on American streets.

Now an undeclared, unauthorized, unpopular, and unconstitutional war of aggression against Iran has spread like wildfire through the region and into Europe. A new “forever war”—with an ever-increasing likelihood of American troops on the ground—may very well be upon us.

As we’ve seen over and over, this administration uses lies, misdirection, and attempts to flood the zone to justify its abuses of power at home and abroad. Just as Trump, Marco Rubio, and Pete Hegseth offer erratic and contradictory rationales for the attacks on Iran, the administration is also spreading the lie that the upcoming midterm elections are under threat from noncitizens on voter rolls. When these lies go unchecked, they become the basis for further authoritarian encroachment and war.

In these dark times, independent journalism is uniquely able to uncover the falsehoods that threaten our republic—and civilians around the world—and shine a bright light on the truth.

The Nation’s experienced team of writers, editors, and fact-checkers understands the scale of what we’re up against and the urgency with which we have to act. That’s why we’re publishing critical reporting and analysis of the war on Iran, ICE violence at home, new forms of voter suppression emerging in the courts, and much more.

But this journalism is possible only with your support.

This March, The Nation needs to raise $50,000 to ensure that we have the resources for reporting and analysis that sets the record straight and empowers people of conscience to organize. Will you donate today?