What’s Next for the Left in Venezuela?

If revolution is to win again in Venezuela, its backers at home and abroad must first recognize that they lost.

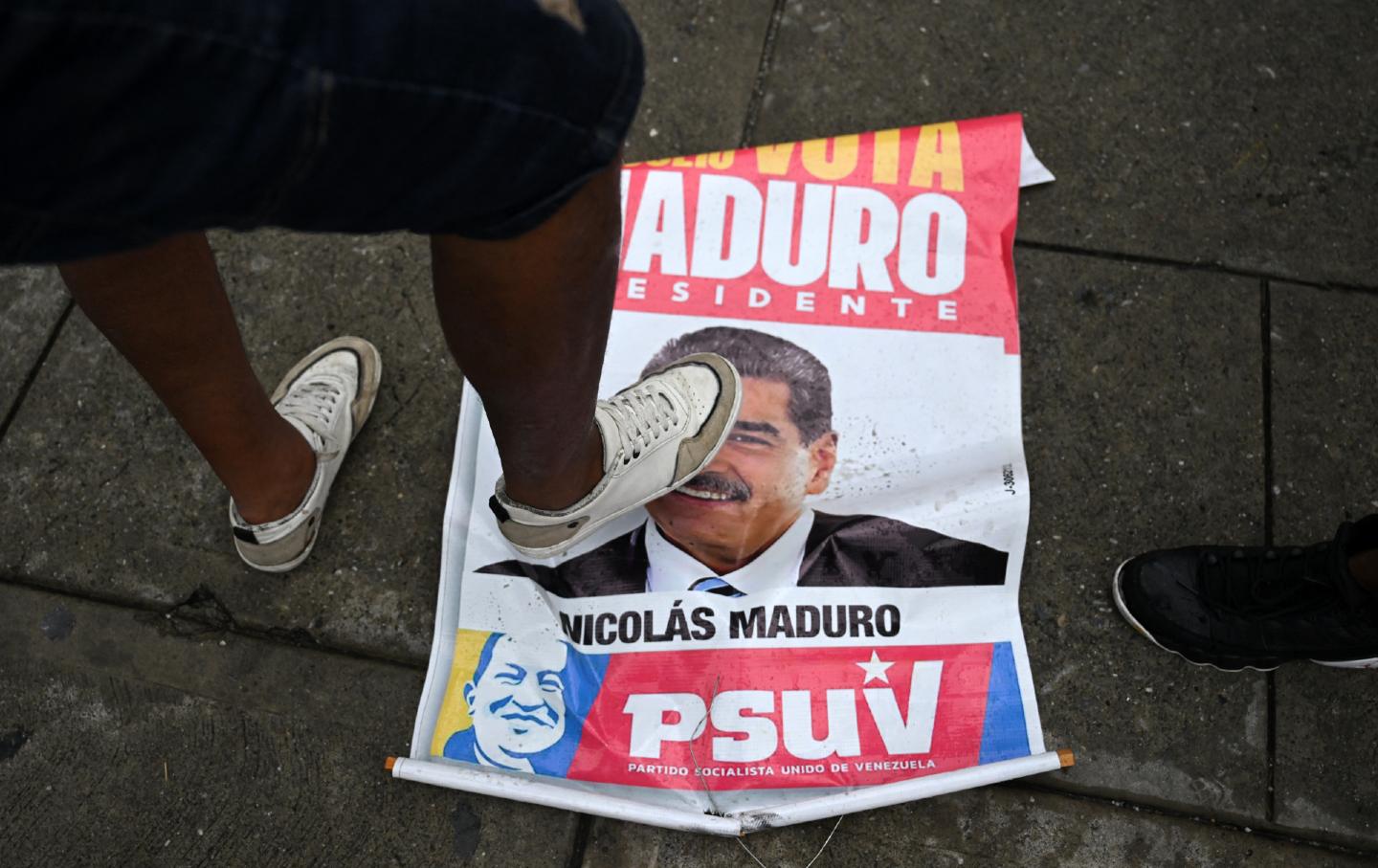

An opponent of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro’s government steps on an election campaign poster with the image of Maduro during a protest at the Petare neighborhood in Caracas on July 29, 2024, a day after the Venezuelan presidential election.

(Raul Arboleda / AFP via Getty Images)

At a glance, it seems all too familiar. Another hotly contested election in Venezuela, another victory for the long-besieged Chavista government, another round of fraud allegations by the US-backed opposition.

It is a well-worn script that has played out repeatedly for nearly 25 years. It did so in 2004 when, following a coup attempt, an oil industry strike, and violent protests aimed at ousting Hugo Chávez, opponents mounted a bid to recall the president only to falsely claim fraud when he won handily. It did so in 2012 when a cancer-ridden Chávez secured another resounding victory despite pre-election polls projecting an opposition win, sparking new, unproven vote-rigging allegations. And it did so in 2013 when, a month after Chávez’s death, his handpicked successor, Nicolás Maduro, eked out a narrow majority to claim the presidency, resulting in protests and more claims of fraud, once again unsubstantiated.

Against this backdrop, it may be tempting for those who backed or still back what Chávez called a Bolivarian Revolution—a movement that aims to make Venezuela and later the rest of Latin America more responsive to popular needs—to dismiss opposition claims that Maduro stole elections for a new six-year term of office. All the more so when the US government has announced that it will recognize the opposition victory even as most countries in the region withhold making that call. (The US’s own efforts to oust Chávez and later Maduro have ranged from targeted sanctions to funding a fictitious government-in-exile to launching a “maximum pressure” campaign aimed at isolating Venezuela and strangling its economy.)

But the reality is that this time is different. Ten days since the vote, there can be little doubt that Maduro lost his bid at reelection and that his government intends to remain in power, defying the will of Venezuelan voters. The evidence is partly in the continued refusal by electoral authorities to release precinct level data for public scrutiny, as it has speedily done in previous elections and as the law requires, or to offer proof of what it claims is a “brutal hacking campaign” targeting its election system. Evidence also lies in the opposition’s own online platform’s hosting copies of what appear to be over 80 percent of precinct returns giving opposition candidate Edmundo Gonzalez a two-to-one margin of victory. And it lies in public statements by governments otherwise friendly to Chavismo—in Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico—conditioning recognition on an independent audit of the results announced by the National Electoral Council.

But perhaps the strongest evidence is in the streets. In the days since Maduro’s putative victory, sometimes violent but more often peaceful protests broke out throughout Venezuela. Unlike prior rounds of post-electoral unrest largely involving stalwart opposition supporters among the country’s middle classes, these protests began in areas where Chavismo has long held sway, in the barrios and popular sectors at the heart of Chávez’s political project. To date, clashes with security forces have claimed nearly two dozen lives and led to more than 1,000 arrests.

Officials blame outside agitators trained in Texas. But to believe that is to willfully ignore what the last decade has wrought in Venezuela and what it has meant for Chavismo’s once powerful, majoritarian popular appeal. In the years since taking office, Maduro has diverted dwindling resources from declining oil prices to an inner circle of supporters, especially in the military and security apparatus, to shore up government control. That has meant slashing or outright eliminating social programs and participatory mechanisms that were hallmarks of Chavismo.

As discontent from grassroots Chavistas grew into protests, Maduro responded with special police operations nominally aimed at fighting crime and that targeted urban youth, resulting in thousands of extrajudicial killings intended to keep barrios at bay. More recently, in a bid to combat hyperinflation and capitalize on remittances from over 7 million Venezuelan migrants abroad, Maduro dollarized the country’s economy, leaving those with minimal access to meager state support or remittance income to fend for themselves.

To be sure, US sanctions have exacerbated Venezuela’s crisis. But they are not its cause nor do they explain why sectors loyal to the government for 25 years turned away from it at the polls. Instead it is the combination of austerity, corruption, repression, and dollarization under Maduro, all of it hitting Chavismo’s historic bases of support, that for the first time swung the presidency to the opposition.

But whether this is the end of Chavismo is a different question, one that left solidarity will play a critical role in answering. Even if the opposition has at last won the presidency, it will face gargantuan challenges in power. After remaking the state, Chavismo controls all government institutions, including the National Assembly, most governorships and mayorships, the military and police. If it is to be, as it has long claimed, a democratic alternative to Chavismo, the opposition will need to operate within rather than purge the Chavista state. Moreover, even as it maintained remarkable unity on the campaign trail, the opposition consists of a wide range of ideological actors. The strongest voices have called for implementing an orthodox neoliberal agenda, privatizing the state oil company and public education and dismantling what remains of social safety nets in favor of private enterprise and foreign capital. Whether that agenda will carry the day or fracture the opposition coalition remains to be seen.

More on Venezuela:

Above all, an opposition in power will need to contend with its major weakness: taking popular sectors for granted or worse, dismissing them outright. Yes, those sectors have turned against what has become of Chavismo. But to assume they have given the opposition carte blanche is a stretch at best. So too is assuming they have turned against all that Chavismo once stood for. Helping to rebuild rather than dismantle social programs and participatory mechanisms will be crucial in any political scenario that follows. Supporting that work and defending the people who were once Chavismo’s core should be the centerpiece of left solidarity. But if it is to have any credibility in doing so, the left must first defend popular sovereignty.

For the left, the choice is between supporting a person or a process, a choice Chávez himself understood. Facing a difficult reelection in 2012, what proved to be his last, he spoke candidly to the press about his prospects. “If I lose…I would be the first to admit it and hand over the government, and I would call on my followers, civilian, military, from the most moderate to the most radical, to obey the will of the people. As we should, because it wouldn’t be the end of the world for us. A revolution doesn’t play out in a day, it plays out every day.”

On July 28, Maduro lost. If revolution is to win again in Venezuela, its supporters at home and abroad must first recognize defeat and the many missteps that led here, then begin the work of supporting Chavismo in opposition, not in power.