Chile at the Crossroads

A dramatic shift to the extreme right threatens the future—and past—for human rights and accountability.

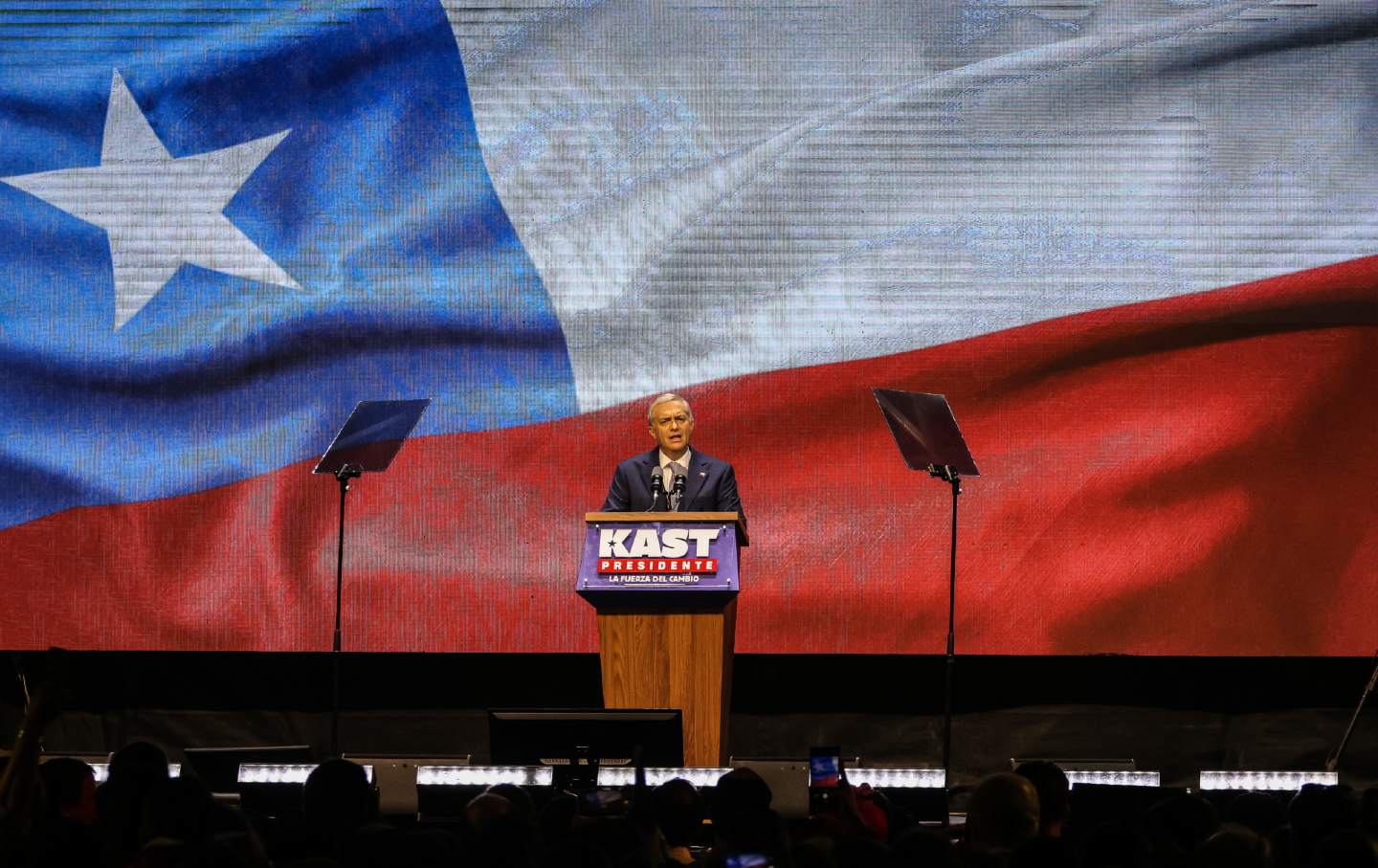

This past Monday morning, Chileans awoke to a new reality. Some 35 years after the return to civilian rule following the infamous Pinochet dictatorship, Chile will soon be governed by a rabid right-wing, pro-Pinochet apologist—President-elect José Antonio Kast. For the 58 percent of the Chilean public sold on Kast’s Trumpian anti-immigration and pro-security populism, that was great news. But for the 42 percent of Chileans who voted for progressive candidate Jeannette Jara, Chile’s swing to the far right is devastating, and a bitter political pill to swallow. As the outcome became apparent on December 14, a meme circulated on Chilean social media: “Paso a paso nos vamos… a la mierda.” “Step by step we are going… into the shit.”

Already the transition of power has begun. Kast met this week with Chile’s outgoing President Gabriel Boric, adopting a civil tone and vowing respect for those who opposed him. But given his family background—Kast’s father was a member of the Nazi party in Germany, and his brother served as a minister in the Pinochet regime—and his repeated promise to exercise the “mano dura” (the iron fist) once he becomes president, there is a deep foreboding among Chileans still traumatized by the atrocities of the military dictatorship—and still committed to redressing them. “The election feels like a referendum on unfinished history,” one Jara supporter told me.

Indeed, for Chile’s significant human rights community, the election of an avowed Pinochet admirer can only be interpreted as political validation of the former dictator’s reign of terror. When Kast is inaugurated in March, his ultra-hard-line government portends a dire challenge to ongoing efforts to remember and repudiate Chile’s violent, authoritarian past.

Purveyors of Denialism

Since 1990, when Chile’s pro-democracy movement succeeded in pushing the entrenched dictator from power, successive governments, along with Chilean civil society and human rights organizations, have attempted to process the evils of Chile’s past. The Chilean judiciary has prosecuted hundreds of human rights violators from the military era; some 139 former high-ranking military officers remain incarcerated for their human rights crimes and additional cases are pending. The government has built human rights museums, transformed secret police torture camps into educational centers, and established “memory sites” as monuments to the atrocities committed by the Pinochet regime and in recognition of its thousands of victims.

As part of Chile’s nunca mas—never again—campaign, just two short years ago President Boric hosted leaders from around the world to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the US-backed September 11, 1973, military coup. His message: remembering the past and renewing a commitment to a stronger democratic future with respect for human rights and political differences. “Problems with democracy can always be solved,” Boric told an audience of several thousand who had gathered on the grounds of La Moneda palace, “and a coup d’état is never justifiable—nor is endangering the human rights of those who think differently.”

Boric also used the occasion of the 50th anniversary to launch a new government initiative called the “Plan Nacional de Busqueda” (PNB)—the search for the disappeared. More than 1,100 Chileans (and one US citizen named Boris Weisfeiler) remain missing at the hands of Pinochet’s repressors; the State was responsible for disappearing them and the State should be responsible for finding them, Boric asserted as he inaugurated the special investigation. In a recent speech on human rights largely devoted to defending the PNB and the need to continue its investigative efforts, Boric denounced “the insolence and profound error of those who maintain that this matter can be swept under the rug.” The work of the PNB was not only to account for the desaparecidos and bring closure for their families, he emphasized, but to educate the public on the realities of Chile’s dark history “so that this does not happen again.”

But Kast and the members of his extreme-right Republicano party are Chile’s leading carpet sweepers; the Plan Nacional de Busqueda, which operates under the human rights unit of the Ministry of Justice, is likely to be the first victim of the new president’s efforts to close the door on further investigations of Chile’s repressive past. As the leading purveyors of what the Chileans call “negacionismo”—denialism—the Republicanos and the other conservative parties have repeatedly minimized and dismissed evidence of the Pinochet regime’s human rights atrocities.

In the middle of the campaign last September, for example, when news broke that PNB investigators had found one of the disappeared alive in Argentina, pro-Kast legislators sought to discredit all the disappeared, and those seeking to find them. The unique case of former militant Bernarda Vera became a political weapon on the right to imply that there were many other desaparecidos who were not dead and that their families were fraudulently receiving government reparations for human rights victims. The diligent investigative work of the PNB itself came under severe right-wing political attack, leaving its future in doubt. “Kast will shut it down,” one veteran human rights investigator predicted with certainty.

Other leading institutions of Chile’s commitment to memory and accountability for the Pinochet regime’s atrocities are also threatened. Although Kast will not have a conservative majority in the Chilean legislature, his electoral mandate to cut public spending will certainly include defunding major “memory sites” that are part of Chile’s renowned historical landscape devoted to human rights. Chile’s legislature has already passed appropriations for 2026, but thereafter the future of Santiago’s iconic Museum of Memory and Human Rights, which counts half a million visitors a year, will be in jeopardy. So too is the future of the former death camp, Villa Grimaldi, run by Pinochet’s feared secret police, DINA—now a landmark memory site in Santiago.

Other former DINA torture centers that have been transformed into educational museums are also likely to end up on the Kast administration’s human rights chopping block, as are the publicly funded monuments to the disappeared and executed political prisoners at the National Cemetery. “If Kast becomes president, we are all in a panic,” one leading human rights official told The Nation before the elections.

Pardoning Pinochet

Kast’s ascendency comes on his third electoral attempt; four years ago, he was defeated by a 12 percent margin by Boric, who rode a wave of public discontent with Chile’s staggering inequality to become, at age 35, the youngest president in Chilean history. But Boric’s agenda of redressing his country’s socioeconomic disparities has been overwhelmed by a dramatic shift in national preoccupation to rising violent crime linked to immigration, mostly from Venezuela. “The issue is security, security, security,” a taxi driver told me during a recent research trip to Chile.

In many ways, Kast’s brand of “security populism” mirrored Donald Trump’s own winning electoral strategy a year ago. Like Trump, Kast promised to build a border wall, along with digging trenches, to keep migrants from crossing into Chile from Peru and Bolivia. He has threatened to deport hundreds of thousands of undocumented immigrants. “If you don’t go on your own, we’ll detain you, we’ll expel you, and you’ll leave with only the clothes on your back,” Kast declared in one campaign video. “Chile First” became a familiar campaign slogan. Kast supporters wore the Chilean version of MAGA hats and T-shirts—Make Chile Great Again. “Under his leadership, we are confident Chile will advance shared priorities to include strengthening public security, ending illegal immigration and revitalizing our commercial relationship,” US Secretary of State Marco Rubio stated in a congratulatory message to Kast.

In his campaign against Boric four years ago, Kast broke a taboo of post-dictatorship Chilean politics and openly endorsed the Pinochet regime. Pinochet “would vote for me if he were alive,” Kast famously declared. Perhaps more ominously, he made a political point of visiting Pinochet’s convicted henchmen in the special prison, Punta Peuco, that was built to house convicted human rights violators—and promised to pardon them for their atrocities.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Although Kast has been more circumspect about expressing his admiration for the Pinochet era during his victorious 2025 campaign, his commitment to pardon those convicted of human rights atrocities remains controversial. During the debates with Jara, Kast was questioned about the pardons for seemingly unpardonable crimes; due to their old age, he responded, the torturers and executioners deserved to be released. “We learned that the same candidate who speaks of using the iron fist against delinquents…now wants to use pardons to liberate some of the worst criminals of our history,” noted one of Chile’s leading journalists and commentators, Daniel Matamala. “If there is something that distinguishes the delinquents of Punto Peuco, it is the sadism and cowardice with which they committed their crimes.”

But just like Trump pardoned the January 6 insurrectionists to rewrite the history of his criminal efforts to instigate a coup, a Kast pardon of Pinochet’s duly convicted officers will signal a mendacious attempt to whitewash the terrorist history of the military dictatorship—and, in effect, provide a posthumous pardon to Pinochet for his crimes against humanity.

That is the ultimate danger of Kast’s hostility toward ongoing efforts to pursue legal and historical accountability for the victims, and the survivors, of the military era—a danger that conscientious Chileans, including those who led the struggle to restore democracy to their country, will no doubt resist. “Without memory, without truth, without justice, there is no certainty that there will not be a repeat of the past,” President Boric warned in his final International Human Rights Day speech on December 10, just four days before Chile’s fateful election. “And without guarantees that it will not be repeated, the future will not be peaceful.”

Your support makes stories like this possible

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.

More from The Nation

What Edward Said Teaches Us About Gaza What Edward Said Teaches Us About Gaza

On Palestine and the geography of vanishing.

A Day for Gaza A Day for Gaza

Today, The Nation is turning over its website exclusively to stories from Gaza and its people. This is why.

What Happens to the Educators When the Schools Have Been Destroyed? What Happens to the Educators When the Schools Have Been Destroyed?

Hamada Abu Layla spent 22 years earning three degrees from Gaza universities. Now they mock him from a garbage dump.

My Sister’s Death Still Echoes Inside Me My Sister’s Death Still Echoes Inside Me

Rewaa was killed by an Israeli bomb. Her absence has broken me in ways I still cannot describe.

“We Have Covered Events No Human Can Bear” “We Have Covered Events No Human Can Bear”

Journalists in Gaza have bartered their lives to tell a truth that much of the world still doesn’t want to hear.

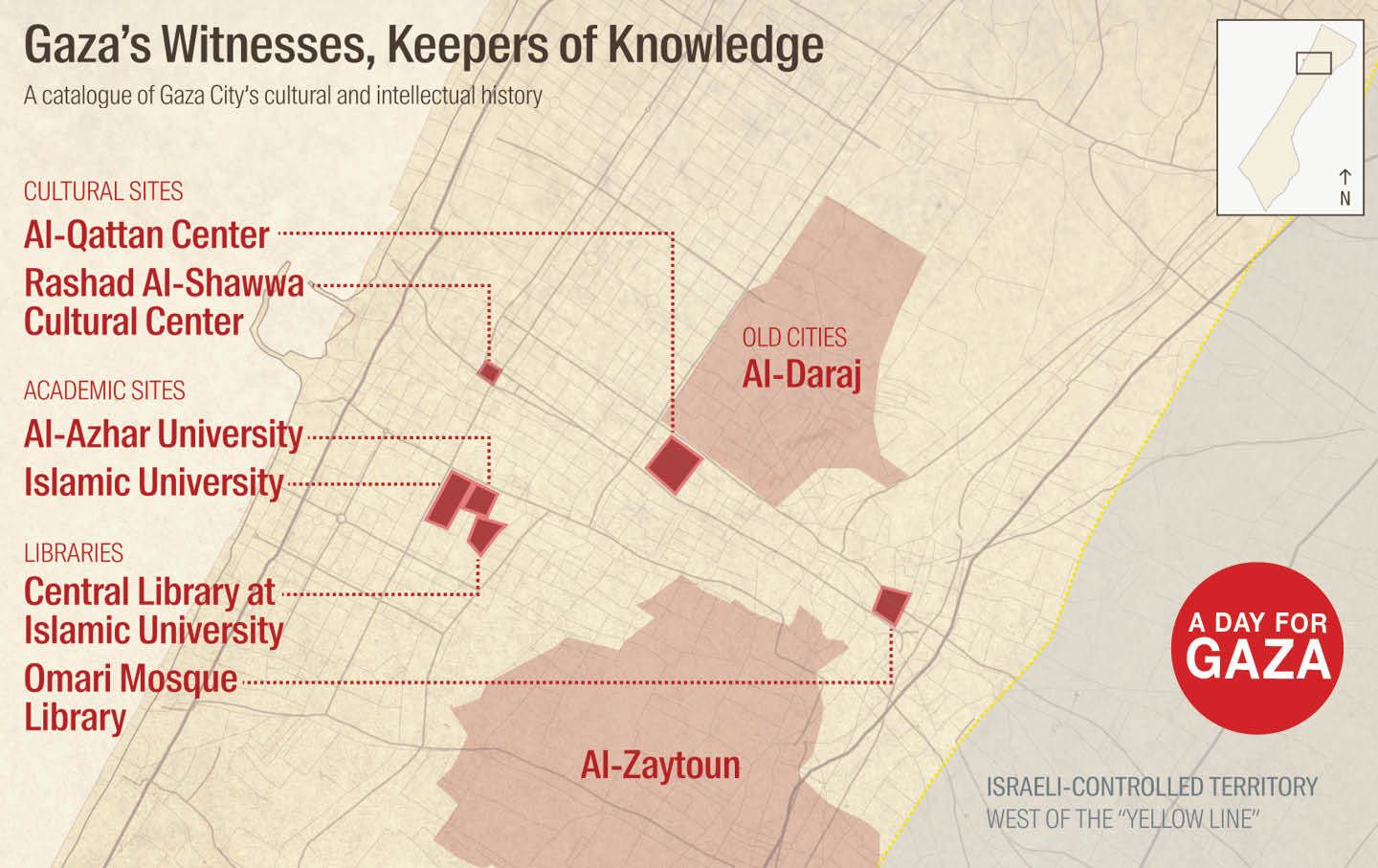

A Catalog of Gaza’s Loss A Catalog of Gaza’s Loss

Recording what has been erased—and making sense of what remains.