On September 19, a group of cab drivers organized by the New York Taxi Workers Alliance rolled up to the corner of Broadway and Murray Street in downtown Manhattan, parked next to City Hall, and declared they would not leave until the city fixed the crushing debt that had driven many of their fellow drivers to suicide. They held a press conference, hung an SOS banner from the nearby Beaux-Arts subway entrance, set up some folding chairs, and sat down to wait.

I stopped by the encampment at midnight to find eight drivers trading jokes on the lonely concrete of the Financial District. Augustine Tang invited me to join them. Thirty-seven years old, with the characteristic swagger of a native New Yorker, Tang had inherited his father’s taxi medallion—the badge that gives cabbies the right to operate—along with $530,000 of debt. He was one of the group’s most eloquent spokespeople and also one of the youngest. His companions were all older, men who had spent decades behind the wheel—like Mohammed Islam, from Bangladesh, who owed $536,000, and “Big John” Asmah, from Ghana, who owed $700,000. At an age when many people are contemplating retirement, these drivers instead faced a future of 14-hour workdays that would bring them no closer to freedom as well as harrowing financial burdens they would pass on to their kids.

But these drivers also knew a way out, which is why they had decided to camp outside the gates of City Hall.

In late September of 2020, the New York Taxi Workers Alliance had drawn up a plan to cap drivers’ loans and limit their monthly payments. The city ignored it, just as, for years, it had brushed off NYTWA’s protests against medallion debt. This sit-in was an escalation—an attempt to force New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s hand.

Inspired by the drivers’ struggle, I kept coming back, night after night, then week after week. I listened to their stories, drew their portraits, marched in their picket lines, and ultimately joined their hunger strike. Despite their defiant assurances of victory, I could not shake the sense that I was witnessing the doomed last stand of yet another group of working-class New Yorkers who would be crushed by the hedge-fund Bretts who run this city.

Instead, on November 3, NYTWA announced that the city had adopted almost every detail of its plan. The drivers had won.

“This victory means everything. It was beautiful to see the unity between the working people,” Tang later told me. “We’ve had cabbies that don’t own any medallions show their gratitude for our fight. We’ve had strangers outside of the industry crying with us after we won. Working people just want working people to succeed.”

The drivers’ victory was a testament to the unifying power of collective labor action. Ninety-four percent of cab drivers are immigrants, and 95 percent are men, but there are few other commonalities among them. Cabbies represent almost every race, religion, and country of origin, and they speak over 120 languages. They spend their days isolated in their cabs, competing for a dwindling number of fares. Yet for decades, NYTWA—a 21,000-member union of cab, livery, and rideshare drivers—had brought them together around their common plight. Now, through relentless work, shrewd organizing, and ferocious solidarity, cabbies had moved the city.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

This is the story of how they did it.

Taxis are a symbol of New York City. Vivid yellow and topped with ads, they speed down Broadway, queue up at the airports, fill every lane on the Friday night Brooklyn Bridge. There are some 13,500 of them in New York, ferrying passengers day and night. What is our city without its chariots?

For decades, a taxi medallion had been considered a blue chip investment—not only for the city but for the New Yorkers who purchased them. A person could make a living driving a taxi and, when they were old, sell the medallion and retire. What made the medallion valuable—and the job of driving a cab viable—was the cap the city placed on the number of medallions in 1937.

But beginning in the aughts, a number of forces conspired to upend the medallion market and devastate drivers’ lives. The first was a speculative bubble that inflated around taxi medallions, thanks in part to a revenue-generating scheme embraced by Mayor Mike Bloomberg’s administration. To plug holes in the city’s budget, the Taxi and Limousine Commission began an aggressive campaign to auction off new medallions in 2004, ultimately adding 1,000 taxis to New York’s streets. Into this expanded market rushed a ravenous group of lenders and speculators who helped drive up prices. Between 2004 and 2015, the price of medallions rose from $200,000 to over $1 million. The city earned $855 million from sales taxes and income from the auctions during this period, and a small group of bankers, brokers, and credit union bosses made a killing.

As medallion prices skyrocketed, the city, lenders, and brokers aggressively targeted the immigrant communities whose members made up the ranks of drivers. “Your chance to own a piece of New York,” touted one pamphlet put out by the Taxi and Limousine Commission. The city dangled promises of steady earnings and secure retirements, and the drivers believed. To pay for the medallions, they took out usurious mortgages whose terms were deliberately opaque. Many of the loans left them on the hook for as much as $4,000 a month, which often included balloon payments, bizarre fees, and dizzying interest rates. Some loans required them to sign over their homes as collateral.

Then, in 2011, Uber arrived in New York. Lyft followed in 2014. Tens of thousands of additional cars flooded the streets, and yellow cab ridership fell by half. In late 2014, the medallion bubble burst. By 2018, medallions were selling for as little as $160,000. Seeing an opportunity to make a profit, Marblegate Asset Management, a Connecticut-based hedge fund, snapped up 3,000 loans—not from the drivers, but from other lenders—for the reported average fire sale price of $110,000.

The drivers, of course, had no such opportunity. They were stuck paying off their original loans, and the crash in medallion prices meant they couldn’t sell. They were caught in a sort of debt peonage, indentured to their creditors and the city.

It was around this time that the suicides began. The first three were among livery drivers, like Douglas Schifter, who had seen their income devastated by the ride-hailing apps. In February 2018, Schifter parked his car outside the gates of City Hall and shot himself in the face. In the suicide note he posted on Facebook, he wrote that, after Uber entered New York, he needed to work 120 hours a week just to scrape by, and that fines, fees, and delays imposed by the TLC had left him deeply in debt. Sixty-one years old and broke, he saw no way out of it.

Schifter’s death shocked the city, finally awakening New Yorkers to the plight of its drivers, but more suicides followed. Over the next nine months, three owner-drivers killed themselves in despair over their unpayable medallion debts: 64-year-old Nicanor Ochisor, from Romania; 56-year-old Yu Mein “Kenny” Chow, from Burma; and 58-year-old Korean immigrant Roy Kim. By the end of 2018, eight drivers had taken their lives.

Given the financial despair that had engulfed most taxi drivers by the late 2010s, it might not seem surprising that they eventually massed to protest the conditions in the industry. Yet despair alone rarely leads to collective action. That requires something else.

When a Bronx community radio station called Bhairavi Desai at the end of 2017 to tell her about the first two driver suicides, she was devastated, but not surprised. As the executive director of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, Desai had intimate knowledge of the problems bedeviling her members. The daughter of Gujarati immigrants who moved to New Jersey when she was 7, Desai started organizing cabbies in 1996, at the age of 23. She spent her days hanging out at gas stations, garages, and South Asian restaurants until, through sheer pavement-pounding grit, she had gotten to know hundreds of drivers. Within a year, she and some friends had formed a union.

A small woman with a breathy voice and an iron will, Desai has become a legendary figure in the cabbie community—one former driver, Paul Gilman, described her as his “idol.” Drivers often turn to her to share their emotional and economic pain, and as far back as 2015, she had begun to sense that something was very wrong. It began when a member of NYTWA, Jaswinder Singh, blanketed driver hangouts with flyers that read: “If you have a loan with First Jersey Credit Union and can’t pay it off, let’s go to the union together so we can fight.” The drivers called a meeting at the NYTWA office and then, with Desai, went to the credit union. Desai found the credit officers obnoxious and disrespectful, but the drivers were ecstatic; this was the most helpful that First Jersey had ever been. “Afterwards, we went to a Dunkin’ Donuts across the street, where we shared hot chocolate and tater tots. I realized how much people were struggling: We were nickel-and-diming what we were able to eat,” Desai said.

At first, much of NYTWA’s work on medallion debt took place behind the scenes. The union was busy pressing an ambitious related campaign—the need for a cap on the number of Uber and Lyft cars, as well as a minimum-wage standard for their drivers—and that effort was the focus of its public protest. (The group succeeded in winning the cap in August 2018.) Even so, Desai and other NYTWA organizers made time to accompany drivers to meetings with lenders. She wrote letters to help them get loan modifications and collected data on their ballooning debts. Still, she hesitated to call her press contacts, even when she learned about the first two suicides. What if no one cared? Wouldn’t that just push more drivers to despair?

That changed when Schifter shot himself in front of City Hall. “When Douglas committed suicide, we did a vigil,” Desai said. “We have never left the streets since then.”

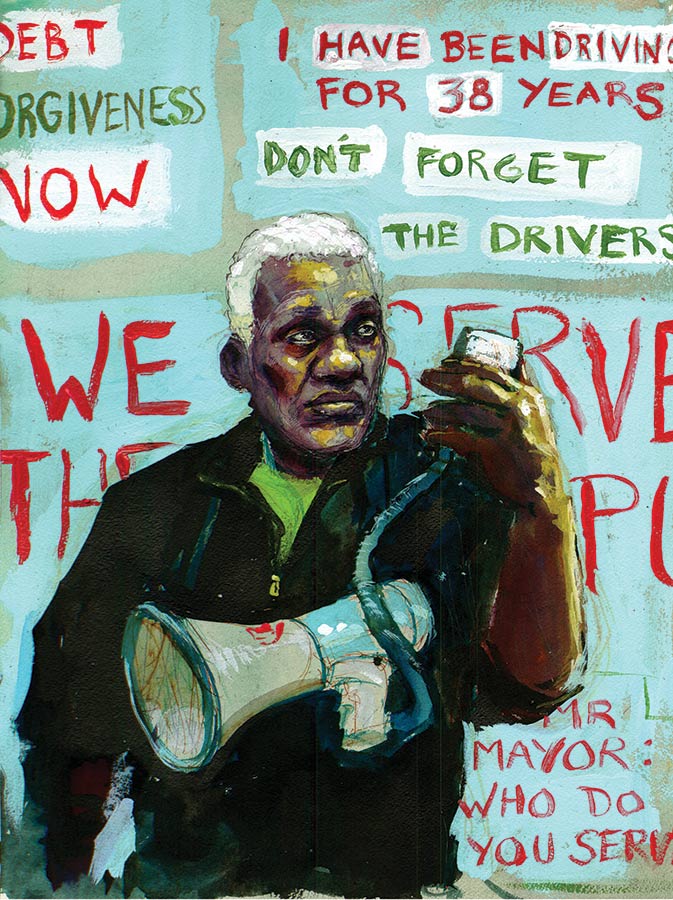

Indeed, between late 2019 and the fall of 2021, NYTWA staged more than 100 protests. I live in the Financial District, and these would become a near-constant backdrop of my days. One day, drivers would shut down the Brooklyn Bridge. The next, they would drive their vehicles in a caravan, honking and holding signs out the windows, and the next they would march in front of City Hall, pounding drums and shouting, “City lies! Drivers die!” as office workers jostled around them indifferently.

If it was the suicides that brought the taxi workers into the streets, it was the arrival of the coronavirus that pushed them to the gates of City Hall. The pandemic decimated the taxi industry. By April 2020, just weeks after New York City shut down, only 982 cabs remained on duty. While taxi drivers had struggled to pay thousands of dollars a month in medallion debt before Covid-19, the prospect of doing so during a pandemic became a farce.

Dorothy Leconte, a 64-year-old driver from Port-au-Prince, was among the many who watched the pandemic shatter the last remnants of what had once been a viable livelihood. In 1987, she had been a single mother with a miserable job cleaning rooms at the Waldorf Astoria, when one of the city’s rare female cab drivers showed her a way out. Within two years, Leconte had bought a medallion. Working 18-hour days and using her medallion as collateral, she was able to earn enough money to send her two boys to private school. She was over $500,000 in debt, but this didn’t become a serious problem until Uber showed up. Her income dropped and her credit card debts rose. Then came Covid. Her ex-husband, also a driver, died of the disease, and her son turned to Leconte for rent. The bills kept coming. She began to work for Amazon Flex, delivering packages with her own vehicle. Unable to afford her taxi insurance, she gave her plates back to the TLC and turned to driving for Uber. “It was pure slavery,” she told me.

To respond to the need, NYTWA organized mutual aid. The union got food and medicine to ill drivers, helped them apply for unemployment. Desai started a weekly radio show that attracted audiences of over a thousand. Every Friday night, she held Zoom meetings that went on for hours, where she helped drivers understand the intricacies of their debts.

NYTWA also came up with its debt-relief plan. Lenders would restructure the loans, capping the amount each driver owed at $125,000 (still enough for Marblegate to make a modest profit), and the city would act as a backstop by guaranteeing the loans. Payments wouldn’t exceed $800 a month.

Officials like New York Attorney General Letitia James and New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer backed the plan. Most visible was Assemblymember Zohran Mamdani, a charismatic democratic socialist from Queens who had campaigned on a promise to end excessive medallion debt. Once in office, Mamdani made sure to follow through, bringing up the cabbies’ plight over coffee with Senate majority leader Chuck Schumer. Schumer had worked with the union before and was sympathetic—his father-in-law had been a cab driver, and he had fond memories of sitting with him at the Belmont Diner in Queens, talking with the other drivers. He was also about to give New York $22 billion worth of Covid-19 relief funds. “We decided that I’d tell the mayor that I hoped he would use some of the money to help the cab drivers, which I did early on,” Schumer told me.

But rather than embrace the plan, de Blasio revealed one of his own. In March 2021, his administration put forward a proposal in which the city would set up a $65 million fund to provide cabbies with $20,000 loans that they could use as leverage with the banks, plus up to another $9,000 in relief. That was it.

NYTWA was underwhelmed. “I knew it was going to leave people at $300,000 debts, if they were lucky,” Desai said. “Twenty thousand dollars was never going to give them the leverage they needed to get actual debt relief.”

So the union balked. “Most would have expected us to settle with whatever was being offered, or at the very least…accept [the administration’s] step as some sort of beginning, but we remained adamant that their approach was not sufficient and that we needed a city-backed guarantee to reduce the debts to the point that drivers could survive,” Desai told me.

This, she said, made all the difference.

What gave NYTWA the courage to reject the mayor’s plan was the amount of organizing it had been doing. Over the previous two years, with unrelenting work, research, and events, the union had consolidated a core base of 300 activist-members. With this army in place, NYTWA had the confidence, and the drive, to escalate the fight. “We had to get the attention of the whole city, both those in power and the broader public,” Desai said.

On September 19, NYTWA did just that when it set up its protest camp outside City Hall. Its demands were almost the same as the ones issued in its original plan, and the deadline it gave the city was the end of the month, when the Taxi and Limousine Commission’s rules hearing would take place. If the city didn’t accept the plan, the union would escalate its protest, culminating in a hunger strike.

When I stopped by around midnight on the first night of the protest, there were less than a dozen men, sitting in folding chairs lit by the yellow glow of the streetlights. When I visited a few days later, at least 30 drivers and supporters were marching with picket signs. Each day, the encampment’s infrastructure grew, until it took up half a block. It was bordered on the south by American flags and union banners, on the north by a memorial for the drivers who had killed themselves, and on the east by parked taxis and tables laden with rice and chana cooked by Lakhwinder Sehra, nicknamed Didi (Hindi for “big sister”), whose brother was an NYTWA driver. I’d often arrive in the middle of a picket, where the raucous chants of Mr. Isaac, a Haitian driver who was once an internationally touring musician, mixed with the drumbeats of Mr. Gyatso, a Tibetan driver from Darjeeling who spoke nine languages. Both men were hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt.

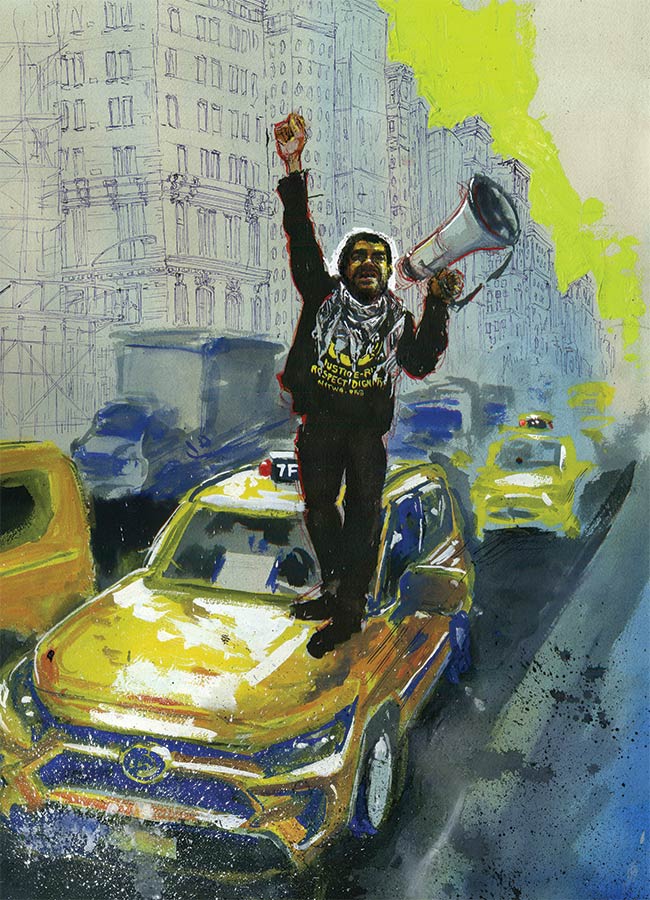

At the head of most marches stood NYTWA organizer Mohammad Tipu Sultan, a slim wire of energy in a keffiyah, bullhorn always in hand. A former driver from Bangladesh, he was proud to share a name with the 18th-century ruler of Mysore, a legendary warrior against the British, and came from a tradition of activism: His father had supported leftist student organizations during the British era and was jailed for protesting against Pakistan’s repression of Bengalis. “We want justice!” he shouted from atop a parked cab. “Talk to the union!” the drivers responded.

The camp had a family atmosphere, with Didi’s home-cooked lunches and the easy banter of people who have fought together for a long time, but this covered a deep tragedy: Drivers had lost their health and were on the verge of losing their homes. At a press conference on October 18, an older Ethiopian driver named Berhane Girma limped up to the microphone. He was frail and on the edge of tears. His right leg dragged behind him: the result of a stroke, he said, brought on by stress over his debt.

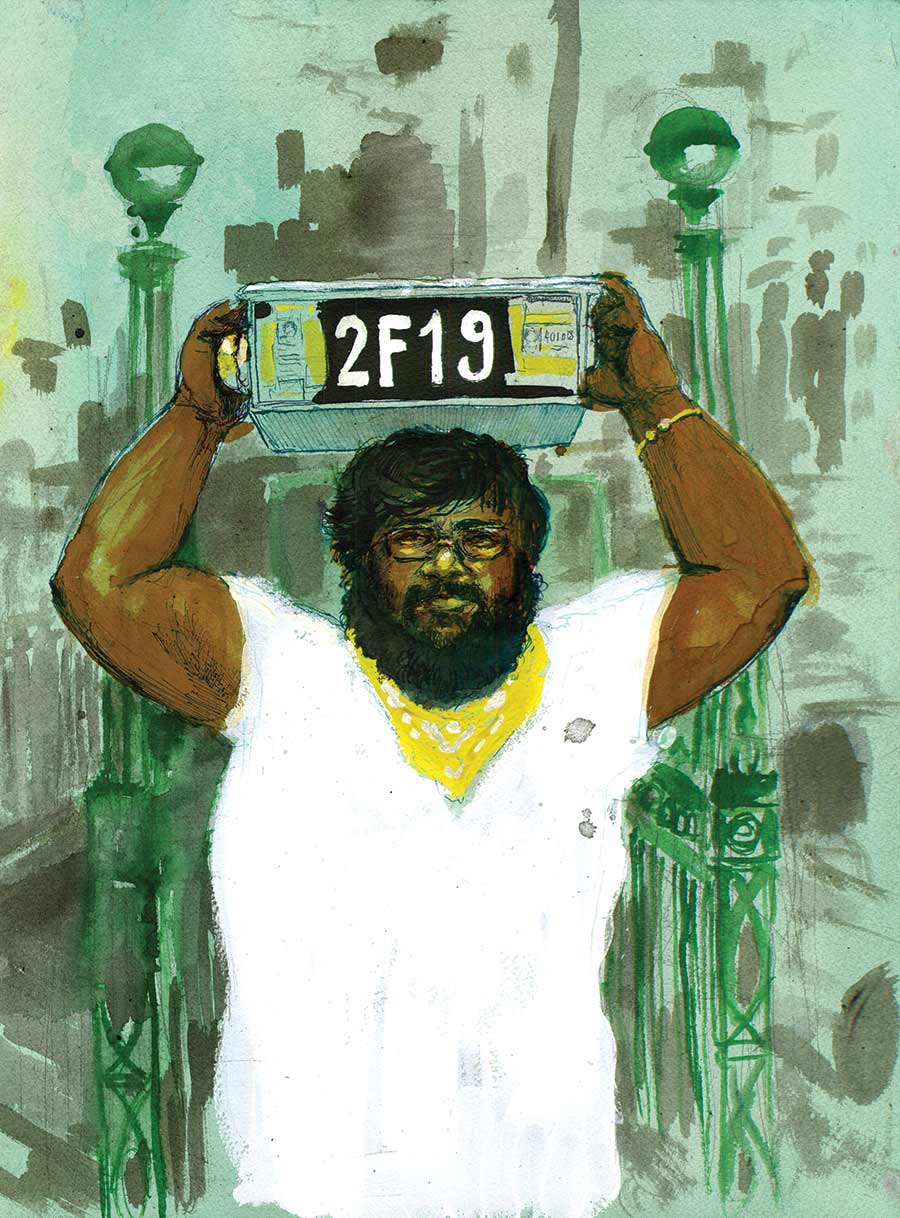

He was followed by Kuber Sancho-Persad, the 26-year-old son of Trinidadian immigrants, who held his father Choonilal’s taxi light over his head like a standard. With his medallion in foreclosure and his wife battling cancer, Choonilal had died of an aneurysm in 2017. His son, now a cabbie himself, inherited the debt and still owed $570,000. “It was supposed to be the American dream, but it became the American nightmare,” he told the crowd. “They took my dad’s pride.”

As the protest continued, more politicians came out in support of the strikers. While it’s not uncommon for New York pols to pop up at protests, their support has felt different in recent years, as a rising cohort of progressive electeds has embraced a more activist approach. Seventy-four New York elected officials signed a letter backing NYTWA’s debt-relief plan. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who had been an early champion, stopped by the camp. Schumer and Mamdani took a ride with Richard Chow, a quiet cabbie from Burma whose brother Kenny had been driven to suicide by the exorbitant debt from a medallion he bought for $750,000. They then shared a video of their trip on social media.

Mamdani was always there, delivering fiery speeches and trying to pitch the story to journalists who felt the issue had already been covered to death. “The grief, trauma, suffering, exploitation, the predatory nature of this entire crisis—that wasn’t new,” Mamdani told me. “The real struggle was how do we break through that.” To draw more attention, he stopped going to his office and did his work from the protest camp. “If someone wanted to meet me about any concern, they’d have to first come and see and hear the sound of the taxi drivers’ struggle.”

Even so, the city refused to negotiate with NYTWA, eventually tripping the deadline for the union’s hunger strike. The night before the strike, I sat drinking deli coffee with Tipu Sultan. He had just led another march around City Hall, and when he spoke, his words still had the cadence of a protest chant.

“My brother Douglas Schifter’s blood is right there. He killed himself with a shotgun,” Tipu Sultan said, gesturing toward the locked gates in front of City Hall. “How does [the mayor] enter there?” His voice rose with emotion. “The system has been failing drivers for over a decade. They start the fight; we’ll finish it. We run this city. This is our city. We run these streets.”

The hunger strike began on October 20. Gatorade replaced Didi’s rice and chana, and doctors set up shop. Each day, NYTWA held a ritual to welcome new hunger strikers: Sitting in folding chairs and surrounded by picketers, the strikers would get up one by one to receive a blessing from Didi, who would then hand them coconut water and pin a red ribbon to their chests.

Over the next two weeks, 78 people joined the hunger strike at various points, six of whom fasted from the beginning till the end, a total of 14 days. About half the strikers were NYTWA members, including Desai, Leconte, Tang, Sancho-Persad, and Chow. The others included family of the cab drivers, like Jaslin Kaur, a member of the Democratic Socialists of America who received its endorsement when she ran for the City Council in 2021; elected officials like Mamdani and fellow assemblymember Yuh-Line Niou; and members of organizations like the DSA, Jews for Racial & Economic Justice, Rise and Resist, and DRUM (Desis Rising Up & Moving).

Wrapped in blankets, the hunger strikers maintained their vigil outside City Hall. The days grew colder, the strikers grew weaker. Still, de Blasio refused to meet. And still the strikers refused to eat.

Each time I passed through the camp, I felt a rising dread. Despite everything NYTWA had done, most New Yorkers knew nothing about the strike. They did not know that aging immigrants were starving themselves to avoid a future of debt peonage. The union tried harder. They got support from the New York chapter of the Sunrise Movement and the actor Kal Penn. On October 25, after five days on hunger strike, Mamdani joined five other elected officials in a sit-down protest in the middle of Broadway and was arrested with them for disorderly conduct.

Meanwhile, Schumer was working behind the scenes. “I came to the conclusion that the previous TLC head, who the mayor sent to negotiate, was not sympathetic and stuck to the old way of doing things. When they went on hunger strike, I decided, working with Zohran and Bhairavi, that I would call the mayor and intervene,” he said.

This, said Desai, finally “brought the mayor to the table.” Schumer was, she explained, the “one voice the mayor would both trust and respect in order to hear us through all the opposition coming from the Taxi and Limousine Commission.” And de Blasio seems to have heard. On October 27, he finally met with NYTWA over Zoom. In an in-person meeting on November 1, representatives of the city sat on one side of the table, Desai and the union members on another. Representatives from Marblegate, the hedge fund that owns the majority of medallion loans, were on a third.

On November 3, NYTWA announced that the city had adopted nearly every detail of its plan. Loans would be capped at $170,000, the monthly payments at $1,122, and the city would act as a guarantor of the debt.

The corner of Broadway and Murray exploded. The strikers broke their fasts with dates and slices of avocado, and Mamdani wrapped Tang in a fierce hug. His voice cracking with emotion, Mamdani grabbed a mike and shouted, “This is just the beginning of solidarity. We are going to fight together until there is nothing left in this world to win.”

That night, I visited the camp. The protesters had hauled out speakers and were blasting bhangra, and the drivers, their supporters, and their families were dancing, applauding, hugging. Tipu Sultan’s daughters were chasing each other through the celebratory crush, while he posed for a photo with his mother, a “revolutionary woman” who held the family together after his father died at a young age. Everyone was snapping selfies. Everyone gave an impromptu speech. Whatever the words, the message was the same: Congratulations. We did it. This victory is ours. We are free.

In a world where left victories are few and the bickering constant, there is much to learn from NYTWA’s success. So when she was recovered from her 14-day hunger strike, I spoke to Desai. What was her advice?

“You have to have the core elements of an organized base of members, a policy, direct action. It needs to be equally creative and militant so it can speak to universal values, as well as capture people’s imaginations,” she told me. “Throughout this thing…we wanted people to know we are going to win. Failure was not an option. So much of the left internalizes defeat. You cannot lead with that. You have to be able to balance the moral high ground with a confidence you can win.”