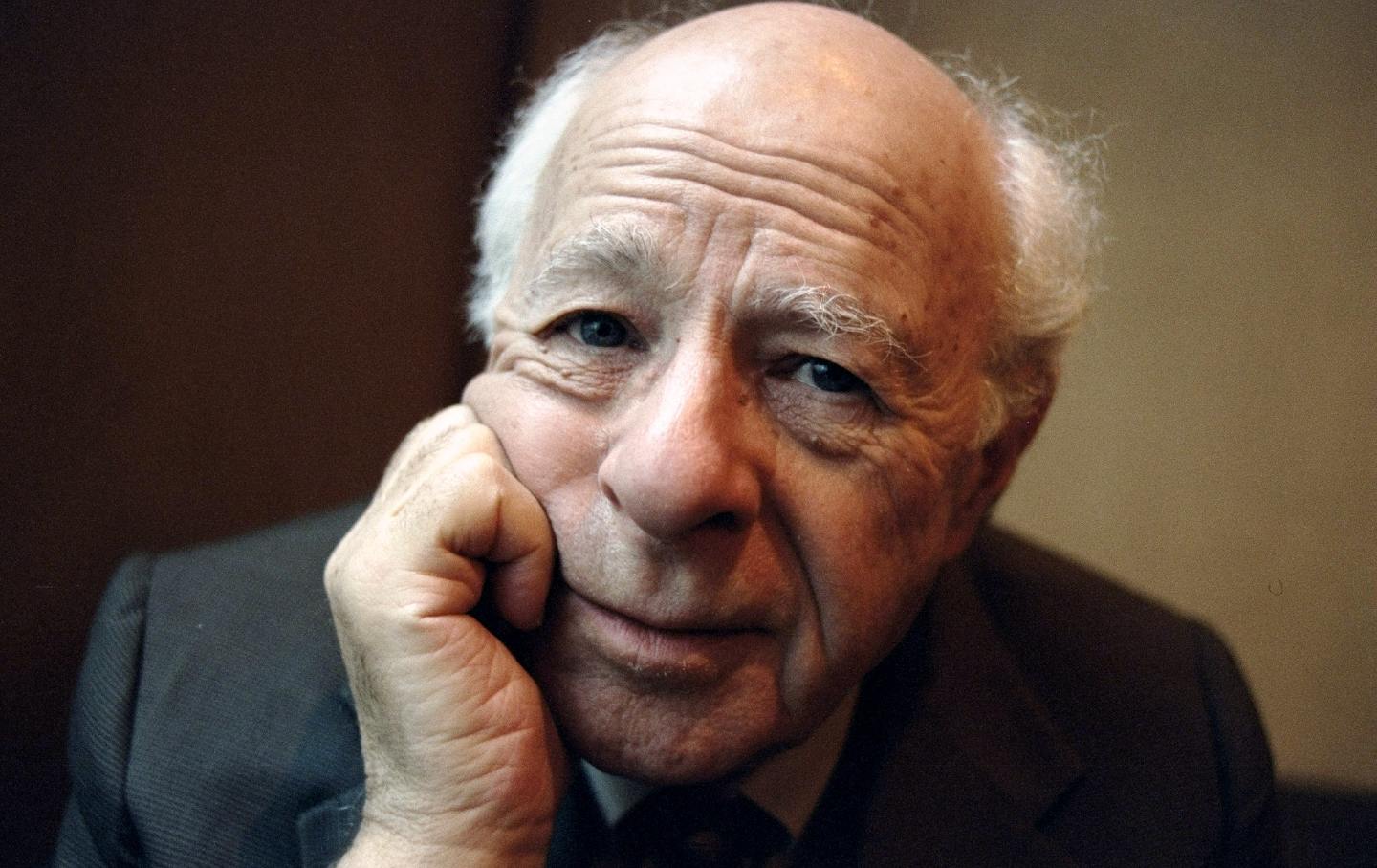

Norman Podhoretz.

(Jon Naso / NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

Postwar Manhattan hosted a tight-knit, disputatious intellectual culture shaped heavily by the sons (and occasionally the daughters) of shtetl-born immigrants. Applying talmudic rigor to secular debates about literature and foreign affairs, they published little magazines whose ideas spread directly from their pages to the highest political offices. While traces of that culture remain—The New York Review of Books, Dissent, and yes, Commentary are all still publishing, as are dozens of other small-circulation journals in the same tradition—its claim on the political zeitgeist has been displaced by a culture that is comparatively dumbed-down, post-literate, and rooted in petty grievances and cheap provocation.

The singular figure who bridged these two sensibilities, Norman Podhoretz, is dead at 95. He was the last canonical New York intellectual, and the first of a now-familiar breed of discourse demagogue.

A star student born and raised in the slums of Brownsville, Brooklyn, to a Yiddish-speaking milkman from Galicia, at the age of 16 Podhoretz took what he called “the longest journey in the world” to the rarefied salons of the Upper West Side, where he studied under Lionel Trilling at Columbia and socialized with the likes of Hannah Arendt, Alfred Kazin, and Susan Sontag. His book reviews, including gutsy attacks on Saul Bellow and Jack Kerouac, earned him early notoriety, and by age 30, he was the editor of Commentary, published since 1945 by the American Jewish Committee, following the suicide of founding editor Elliot Cohen. He held that job for 35 years before handing it off to his like-minded deputy, Neal Kozodoy, who in turn handed it off to Podhoretz’s only son, John.

On Norman Podhoretz’s watch, Commentary was remade twice: at the start of the 1960s, from a somewhat parochially Jewish communal journal to a trendy signifier of countercultural sophistication, and then by the end of the decade into the neoconservative flagship that it remains today. As the runt of the New York intellectual “family” centered on contributors to Partisan Review—the idiosyncratic, anti-Stalinist left-wing literary journal founded in the 1930s—the young Podhoretz was eager to throw off his elders’ tedious, decades-old ideological debates, which had peaked in relevance during his Depression-era childhood. He wanted Commentary to engage with the present, to publish Norman Mailer in opposition to the Vietnam War and James Baldwin on the crisis of the inner city. When the latter defected to The New Yorker for a higher fee for the essay that became The Fire Next Time, Podhoretz responded by penning “My Negro Problem—and Ours,” an unfiltered reflection on his youthful terror of Black bullies that concluded with a reluctant endorsement of mass miscegenation. It was offensive in multiple ways, but it was also buzzy, and so was Podhoretz, who at the height of this era was throwing dinner parties with the newly widowed Jackie Kennedy and making sure everyone knew about it.

Podhoretz was never exactly a man of the left, despite what he would retroactively claim; a decade younger than his City College–educated peer Irving Kristol, he never had a Trotskyist phase in his youth, and while he dallied with the New Left early in his Commentary tenure, that was more about generating attention than any deeper conviction. By default, he was what would now be termed a “Cold War liberal,” but politics was not his guiding motivation. What he sought, quite openly, was literary prestige and the attendant social clout.

In 1967, he published his first original book (he had previously published a collection of essays), the memoir Making It, a shameless bid for greatness that backfired spectacularly. Podhoretz intended to tell his own story as a juicy exposé of what he cast as the dirty little secret of the New York intellectuals—that America’s leading literary critics, despite their high-minded pretense of alienation from grubby capitalism, were actually obsessed with the status hierarchy. To whatever extent that may have been true, insightful, and even prescient, it was also pure projection, and the release of Making It got Podhoretz laughed out of the exact scene he thought he had conquered. It was a critical and commercial flop, and many of the pans came from people he thought were his friends. (In hindsight, it’s a great read, if not precisely for the reasons he intended.) His considerable ego never recovered.

As he drank away this humiliation—his first big failure made a long-standing problem worse—he also began to process the tumult of the late 1960s. Once a skeptic regarding Israel (in a letter to Trilling following a 1951 visit, he wrote, “They are, despite their really extraordinary accomplishments, a very unattractive people, the Israelis. They’re gratuitously surly and boorish.… They are too arrogant and too anxious to become a real honest-to-goodness New York of the East”), in the wake of the 1967 Six-Day War Podhoretz became one of the Jewish state’s staunchest partisans, seeing it as a manly alternative to the allegedly feminized and neurotic culture of his fellow diaspora Jews. This put him at odds with the emerging Black Power movement, which forcefully criticized Zionism. Black Power activists were also highly visible during the monthslong 1968 public school strike in Podhoretz’s native Brownsville, a low point in Black-Jewish relations. Commentary increasingly became fixated on these alleged betrayals, with Podhoretz fulminating against what he deemed the ingratitude of Black America.

In the dead of winter in 1970, alone and miserable in a dilapidated farmhouse he’d purchased in upstate New York with half of a book advance, Podhoretz had a divine revelation—he realized, as he later told his biographer, “that Judaism was true,” and that he was bound to an ancient covenant that transcended the secular world where he had sought material success. He determined that he would henceforth live his life in accordance with a culturally conservative read on Jewish law as he understood it. Returning from a long paid leave, newly sober and with a reinvigorated sense of mission, he rededicated Commentary to war against the left and everything it stood for. His signature editorial tone increasingly prioritized invective and overstatement over rigor and precision and ruthlessly targeted not only African Americans and Palestinians but also feminists, LGBT people, student radicals, and liberals of all stripes.

Within a few years, he was being disparaged by Michael Harrington and others on the left as a “neoconservative” along with peers like Irving Kristol and Daniel Bell who had recoiled from New Left demonstrations on college campuses. Unlike Bell, Podhoretz and Kristol embraced the epithet and made it their own, with Kristol articulating a fuller version of the concept as skeptical of Great Society welfare programs, hostile to the counterculture, and muscular in foreign policy. In 1972, they both endorsed Richard Nixon for president over George McGovern. In 1975, Podhoretz helped draft the speech that his friend US Ambassador to the United Nations Daniel Patrick Moynihan delivered before the General Assembly in which he denounced a resolution equating Zionism and racism; the speech made Moynihan a hero to many New York Jews and helped propel him to the Senate a year later, when he defeated feminist firebrand Bella Abzug in the Democratic primary.

Though Podhoretz spent the 1970s attempting to roll the Democrats back to the Kennedy era via the failed presidential campaigns of Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson, his 1979 memoir Breaking Ranks formally declared him a man of the right. By the 1980 election, Podhoretz and his wife, fellow neoconservative Midge Decter—at least as gleeful a left-baiter as her husband, and with a particular disdain for the New Left’s sexual proclivities—were ensconced in the Republican camp. Along with Kristol, they had mentored a large brain trust that would occupy many offices in the Reagan administration—notably including their son-in-law, Elliott Abrams, who narrowly dodged prison for his role in the Iran-contra scandal and implicated himself in what is now understood as a genocide in Guatemala.

Podhoretz’s cantankerous personality and zeal for war eventually put him at odds with the Reagan White House; when the once-hawkish president turned to diplomacy with Mikhail Gorbachev that ultimately led to the peaceful end of the Cold War, Commentary cried appeasement and warned that America risked being turned into a passive, neutral Finland as a resurgent Soviet Union conquered the world. Podhoretz was wrong, of course, but that didn’t stop him from declaring victory for neoconservatism as he stepped down from his editorship in 1995. He also declared neoconservatism over, having fully transitioned from an essentially liberal intellectual critique of the New Left into an integral part of the mainstream conservative movement.

He was at least partly wrong about that, too; neoconservatism would prove to be very much a living ideology just a few years later. After the 9/11 attacks, the foreign policy-centric neoconservatism represented by The Weekly Standard, cofounded by Kristol’s and Podhoretz’s sons, played a central role in shaping George W. Bush and Dick Cheney’s response, with catastrophic results for Iraq and for the US’s global stature. It could have been even worse, though—Podhoretz, who cast the War on Terror as a sweeping crusade he called World War IV (the Cold War was World War III), personally advised Bush and Karl Rove to attack Iran as well, but they demurred.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Unlike essentially every other major contributor to Partisan Review, Podhoretz lived long enough to see Donald Trump take over the GOP, and unlike second-generation neoconservatives like Bill Kristol, Robert Kagan, and David Frum, he came to welcome it—at first with reservations, but later with real enthusiasm. “His virtues are the virtues of the street kids of Brooklyn,” he told the right-wing Claremont Review of Books in 2019. “You don’t back away from a fight and you fight to win. That’s one of the things that the Americans who love him, love him for—that he’s willing to fight, not willing but eager to fight.” Where the younger Kristol saw Trump’s boorish behavior as an affront to republican virtue, the elder Podhoretz saw a kindred spirit.

It’s fitting, then, that Podhoretz’s final piece of writing, published this April, landed at The Free Press, Bari Weiss’s latter-day neocon website. It was a valedictory, one last retelling of the heroic Brooklyn-to-Manhattan journey that had already formed the basis of four memoirs and an authorized, hagiographic biography. There was little new in the text itself, but its venue signaled that Podhoretz’s strain of neoconservatism remains alive in spite of being pronounced dead many times over. Just months before Podhoretz’s death, one of the wealthiest families in history purchased The Free Press for $150 million and then installed Weiss at the helm of CBS News, with the apparent aim of winning favor from Trump. Meanwhile, Podhoretz’s son-in-law, Elliott Abrams, is now the chairman of the right-wing Zionist Tikvah Fund, which just received a record-setting $10 million grant from the Trump-controlled National Endowment for the Humanities.

One must imagine Norman Podhoretz happy.

More from The Nation

The Trump Administration Arrested Don Lemon Like He Was a Fugitive Slave The Trump Administration Arrested Don Lemon Like He Was a Fugitive Slave

Lemon’s arrest is not only a clear violation of the First Amendment but also a blatant throwback to the Constitution’s long-discarded Fugitive Slave Clause.

Want to Support the Fight Against Fascism? Boycott Trump’s World Cup. Want to Support the Fight Against Fascism? Boycott Trump’s World Cup.

In this week’s Elie v. U.S., The Nation’s Justice correspondent urges soccer lovers to stay away, takes on the attacks on Alex Pretti, and warns of a dangerous anti-voting bill.

ICE Brutally Dragged This Disabled Woman Out of Her Car. What Happened Next Was Just As Chilling. ICE Brutally Dragged This Disabled Woman Out of Her Car. What Happened Next Was Just As Chilling.

“They laughed at me and told me this wouldn’t have happened if I was a ‘normal’ human being,” Aliya Rahman tells The Nation.

Manhattan Republicans Get a Lesson in Mamdani-Era Self-Defense Manhattan Republicans Get a Lesson in Mamdani-Era Self-Defense

A New York Republican club hosted a seminar dwelling on vigilante fantasies in one of the nation’s safest cities.

The Smug and Vacuous David Brooks Is Perfect for “The Atlantic” The Smug and Vacuous David Brooks Is Perfect for “The Atlantic”

The former New York Times columnist is a one-man cottage industry of lazy cultural stereotyping.

How Online Frat Mobs Target Sexual Assault Survivors How Online Frat Mobs Target Sexual Assault Survivors

A video documenting an alleged gang rape in Florida drew a flood of harassment, threats, and doxxing