When Elie Lamadrid, 18, suggested starting an after-school gay youth club in the winter of 1972, George Washington High School, in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, had been a source of trouble for school administrators and city officials.

At the beginning of the 1970–71 school year, the red brick colonial building in a mostly Black and Latinx community was “in a state approaching anarchy,” according to The New York Times. In March 1970, a group of students and parents attempted to commandeer the school’s cafeteria to protest overcrowding, illegal suspensions, and racist tracking. The demonstrators demanded a community-controlled “grievance table” in the lobby, staffed by parents, to address complaints against teachers and give academic advice. Furniture was toppled, lunch trays flung, and students roamed the hallways singing about revolution. The school sent all 4,500 students home early in response to the “large number of disruptions,” as the Board of Education put it. The next school year was a bit calmer, but the unrest of 1970 had been so extreme that the new principal compared the school to “a recovered heart patient or a recovered alcoholic.”

The late 1960s and early 1970s were revolutionary times across New York City. Nine months prior to the uprising at George Washington High, the police had raided a shabby, beloved bar in Greenwich Village called the Stonewall Inn, sparking a 45-minute brawl. What was at stake in the five nights of protest that followed was the right to emerge from the underground of American society without the threat of harassment, institutionalization, or jail.

After the police stormed Stonewall, activist Morty Manford wrote that those without identification or who were underage or gender-nonconforming were “incarcerated temporarily in the coat room.” The irony of locking queer patrons in the closet was not lost on him. The Stonewall Inn, unlike many other gay bars, also catered to a clientele of trans, gender-fluid, and unhoused teenagers who, because of their age, were barred from other watering holes. Trans activist Sylvia Rivera, one of the leaders of the protests, was 17, and had already been living on the street and involved with sex work for six years. While the importance of trans people of color like Rivera to the movement is gaining more recognition, less is said about their youth—or, how the experience of youth itself, with its particular set of vulnerabilities, might also be radicalizing. From its start, the gay liberation movement was also a youth movement—and one of the primary places from which it spread was high school.

Lamadrid, described as a “Third World woman,” or a woman of color, had been inspired by attending an “encounter group,” a kind of unconventional group therapy popular during the 1960s and ’70s. By this point, George Washington had come under Principal Samuel Kostman, who ate tuna fish sandwiches with students in the cafeteria twice a week and approved what might have been the first public gay-straight alliance in a school. A tract the group published in the underground youth press said Kostman belonged to “the minority of enlightened principals of the New York city public education system.” They also found a supporter in teacher Alexander Levie, a “36-year-old middle classer,” as the article described him. Soon, the Gay International Youth Society was born.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

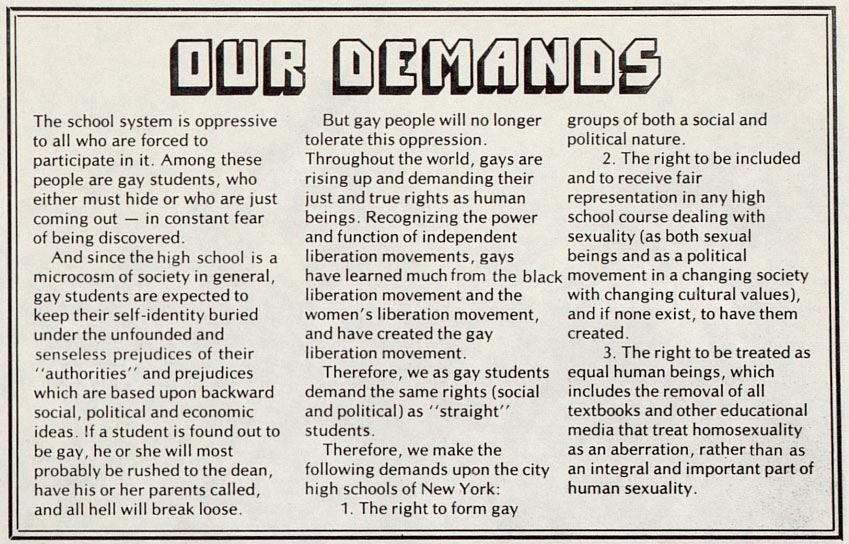

“This present imbalance of student civil rights is political!” the group wrote. The students had three primary demands. They wanted the right to form gay groups. They wanted fair representation in any classes that discussed sexuality. And they wanted to be treated as equal human beings, which they said meant “the removal of all textbooks and other education media that treat homosexuality as an aberration, rather than as an integral and important part of human sexuality.” The students were also organizing on behalf of their teachers, whose jobs were threatened if they were outed. “It is up to these students to create an atmosphere to help them too,” the group wrote. They hoped to form a network of gay student groups in high schools all over New York City. The first order of business, though, was to have what the straight students had always had: a school dance.

Beyond this one piece of writing, little else about their story is documented. As Stephan Cohen writes in The Gay Liberation Youth Movement in New York: ‘An Army of Lovers Cannot Fail’, “Gay liberation school-based groups are an important and largely neglected phenomenon.”

Though most histories trace the first gay-straight alliance to the elite private Concord Academy in Massachusetts in 1989, with Phillips Academy soon following, the George Washington High School club predates this group by 17 years. By the club’s count, there were 20 people in the group, a mix of races, ethnicities, genders, and sexualities that included nine lesbians, six gay men, and five straight allies. They were, as the group wrote, “predominantly Third World,” which is to say part of the global anti-colonial struggle. For Dominique E. Johnson, who discovered the group’s writing as a graduate student researching LGBTQ youth in schools, it was a staggering corrective to the standard narrative. “We still constantly need to say, ‘Whose not at the table? Whose voice is not heard?’” Johnson told me, pointing out how often youth, and especially youth of color, are written out of conventional LGBTQ histories. “We do have the tendency to amplify white cisgender male voices. And that’s definitely not who these young people were.”

The George Washington gay group benefited from other gay liberation and student rights organizing. In 1970, after a massive student mobilization, New York City instituted the Student Bill of Rights, which promised, as Cohen writes, “freedom of expression, end to ‘illegal use of police,’ counseling on abortion, contraception, and the draft, and elimination of racist and sexist tracking.” Donald Reeves, one the school movement’s leaders, wrote in his 1972 autobiography: “The educational system is involved in a conspiracy to miseducate masses of Black and Puerto Rican students…to crush and penalize those individuals who even before birth are doomed to failure.”

The George Washington students in the gay-straight alliance said that the terms set by the Bill of Rights allow students across to city to form their own political organizations. They saw the existing student government as an exercise stripped of any real agency, “a sham” that “acted as puppets” for the adults in power.

Three weeks after the club was formed, the Gay Activist Alliance (GAA), which had already started recruiting in high schools, addressed the George Washington high schoolers in an open forum. Gay rights advocates Manford and Jean O’Leary, from the GAA Speakers Bureau, answered questions and gave advice to the students, whom O’Leary described as “dynamite people.”

If early gay rights groups like the Mattachine Society were afraid to organize with young people for fear of being labeled sexual predators by straight homophobes, post-Stonewall groups saw youths as comrades. In his book, Cohen describes the work of groups like Gay Youth, a subset of the Gay Liberation Front; and the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), led by Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson. Other queer youth organizations—many whose existence Cohen pieced together from listings in the underground press—formed across the country. (Especially notable were the street youth group Vanguard, the lesbian girl gang Street Orphans, and the raucously named Sodom Radical Free Bisexual Communist Youth, all in California.) It was rumored that there were gay groups organizing in high schools around New York City, but the George Washington High School was the first to come out publicly. They advertised throughout the school.

By the end of the 1972–73 school year, the gay liberation movement had fractured. Some lesbian feminists, embattled by sexism in the movement, began to splinter off and would not accept trans women. (Jean O’Leary, for instance, was a vocal critic of trans women, though she later recanted.) When Rivera charged the stage in a zip-up jumpsuit at Washington Square Park for the annual Christopher Street Liberation Days rally—what would become Pride—to the jeers of the crowd, it was a critical moment. In Rivera’s incendiary speech, her voice hoarse, she yelled to the crowd, “I have been beaten. I have had my nose broken. I have been thrown in jail. I have lost my job. I have lost my apartment for gay liberation, and you all treat me this way? What the fuck’s wrong with you all?” On that day, Cohen argues, the gay liberation movement ended.

What happened to the Gay International Youth Society in the wake of such schisms is unknown, but it seems their story, too, is part of the larger forgetting of radical histories, particularly the contributions of people, as Rivera put it in her speech, outside “the white middle-class club.”

By the ’80s and ’90s, Cohen writes, the radical aims of the school gay groups had been eclipsed by a more “incremental civil rights approach promoted by the National Gay Task Force and the Human Rights Campaign Fund.” Los Angeles’s Project 10, formed by a school counselor in 1984, for example, promoted support groups, and advised how to avoid drugs and alcohol, stay in school, and go to college—all necessary badges of the “white middle-class club.” While these groups brought important visibility to queer students during the AIDS crisis, the goal was more assimilationist than revolutionary. Just as the Black Panther Party’s free breakfasts became co-opted by state-sponsored programs, school groups shifted to more of a social services model, based in charity instead of liberation, with adults in the role of “helping” youth, rather than youth autonomously organizing themselves and, as in the case at George Washington, their teachers.

Many of the later queer youth groups, organized around single issues or identities, lost the dream of solidarity that had once brought many together. While the Gay International Youth Society denounced their school as “oppressive to all who are forced to participate,” the later GSAs instead wanted to create safe spaces within it. “In a lot of ways, I think that [groups like Gay International Youth Society] are more radical and more in touch with the present-day queer movement than a lot of the groups were in the ’80s and ’90s,” Cohen told me. “Because one thing that was really clear for all of these groups, high school and otherwise, is that the movement was still understood as a movement.” That was how members of STAR could march alongside the Young Lords, how members of the Gay Liberation Front could stand weekly vigil outside the Women’s House of Detention where Black Panthers were jailed, or Huey Newton could write of the gay and women’s liberation movements that “we should unite with them in a revolutionary fashion.” In theory—if not always in practice—the struggles of queer people, women, and people of color, Cohen said, were seen as interconnected, subject to the same constellation of oppressive institutions that required not just reform but a complete reinvention of society itself.

In classrooms across the country, American history is under attack. But even before the GOP assaults on critical race theory, the stories of queer youth of color were at risk of erasure. Much of queer history is community memory, and many stories were lost during the AIDS epidemic. This is why the story of the Gay International Youth Society is so important. How many other school groups like the Gay International Youth Society, who fought not only for individual rights but collective freedom, were in San Francisco, Boston, Louisville, or Detroit? Many of the stories of underground organizing by queer youth are lost or endangered. And part of what we lose is the idea of gay liberation, which was a liberation for all where the object was not just pride but power.

Fifty years later, the vision of the George Washington students is now a reality, with thousands of queer student groups across the country. The next-generation GSAs—now called Genders & Sexualities Alliances—have expanded beyond the safe spaces of the ’80s and ’90s to focus on building a movement for racial and gender justice in schools. “The youth always lead,” Johnson said. “They always lead, and we always have to listen to them. They’re going to tell us what the future is because they live it.”