The Covid Revisionists Are Endangering Us All

As the possibility of a new pandemic looms, influential figures are telling us we shouldn’t have been so worried about the last one. This spells trouble.

Passengers on a sightseeing bus wear masks on Thursday, January 4, 2024, in Washington, DC.

(Matt McClain / The Washington Post via Getty Images)We seem to be in the midst of a strange period of Covid revisionism. A peculiarly American mix of narratives has been popping up in different places over the past few months. The thing about these takes, though, is that they are totally at odds with each other.

On the one hand, we’re getting a triumphalist tribute to our performance during the first four years of the (ongoing) pandemic. At the same time, we’re being told we got it all wrong in our response to Covid. Either way, these narratives don’t bode well for our future.

Let me give you four short examples of this trend.

First, we have David Wallace-Wells’s New York Times piece on “Who ‘Won’ Covid.” I mean, OK, it’s a little ghoulish to horse-race this after more than 1.1 million American deaths (a number that is likely an undercount), but Wallace-Wells’s bottom line is that hey, we’re not Uganda, Zambia, Chad, Zimbabwe or Mozambique. Or, as he says, the US is “nevertheless closer to the world’s best performers than its worst ones.”

This “nevertheless” carries a lot of weight for Wallace-Wells, because compared to our peer nations in the G7, there is not much to crow about: We did terribly. He acknowledges this, but assures us that, “nevertheless,” we did good, people. Yay. The piece is designed to obfuscate, not elucidate. After reading Wallace-Wells, I feel like we’re winning so much, I am now quite tired of winning, as the oracle of Mar-a-Lago predicted so long ago.

Next, we have a rehash of Covid’s effect on kids, again in the Times. The piece is full of its own certainty: Closing schools was wrong; it was responsible for learning loss; it did nothing to stop Covid’s spread. I am not going to deconstruct the problems with the piece, since no new arguments are offered up. I’ll just direct readers to Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s “Who’s Left Out of the Learning-Loss Debate” and Tressie McMillan Cottom’s “The Real Roots of the Debate Over Schools During Covid,” which provide needed tonics to the constant diet of this mantra that we’ve heard chanted since 2021. But let me just weigh in from a scientific perspective.

The authors portray Covid’s dangers to children as almost trivial, saying “children were less likely to become seriously ill” and linking to an article that rightly suggests that the elderly have the highest risk of serious disease and death from SARS-CoV-2. But the real counterfactual is what mortality looked like in children before the pandemic, not the death rate among their grandparents in the midst of one.

Let’s put it bluntly. Kids aren’t supposed to die, and yet they did. And while it is true that “opening schools, with safety measures” could minimize transmission, safety measures were not equally available to all. But these details get elided in the narrative that is being pursued here.

Our third revisionist text comes from Uri Berliner, the now-former NPR editor whose critique of NPR as captured by the woke mob has caused such a stir. In his piece, Berliner uses Covid as one of his case studies. He declares that progressive bias is to blame for the broad consensus that Covid spread through a Wuhan wet market, rather than because of a lab leak.

While uncovering the ultimate origin of our current pandemic may be difficult for many reasons, the two hypotheses do not stand on equal ground. In fact, NPR reporter Michaeleen Doucleff, a scientist herself, a former editor at the journal Cell, and part of a Peabody Award–winning team for NPR’s Ebola coverage in 2014, wrote a very good piece about the state of the current knowledge on the virus’s origins back in 2023. But Berliner throws the science desk at NPR under the bus, linking instead to articles by conspiracy-minded advocates for the lab leak theory with little direct expertise in virology, evolutionary biology, or epidemiology.

To me, after reading the papers, the weight of the evidence still supports a natural origin for SARS-CoV-2, amplified through the wet markets in Wuhan. That being said, if there was evidence for a lab leak, I’d have little problem acknowledging it. Indeed, if a lab leak were responsible for the biggest pandemic in a century, we’d all want to know and take steps to ensure that it never happens again. But the implication here is that “wokeness” trumps the importance of lab safety and biocontainment for scientists, even those who work with these dangerous pathogens on a regular basis. If Berliner has a case to make against his employer’s ideological bias, using Covid origins as an example of that seems like a stretch.

Our last example of Covid revisionism comes from inside the house, in a compilation of essays by Sandro Galea, the dean of the Boston University School of Public Health. His new book, Within Reason: A Liberal Public Health for an Illiberal Time, chastises his peers in a way that seems off the mark.

First, Galea suggests that public health “got political” during the pandemic, in part as an overreaction to “an empowered right-wing and the Trump administration’s frequent hostility to public health.” This is a deeply ahistorical reading of public health, one that fails to recognize that it has always been political. From its roots in the Industrial Revolution, public health has oscillated between a progressive vision, which was represented by pioneers such as Rudolf Virchow and Friedrich Engels, and a far less liberal one, in which, as Yale historian Frank Snowden has said, “urban cleansing took on a figurative as well as a literal sense, and was seen as a potential solution to the threat posed by the ‘dangerous classes.’” This dialectic has persisted in public health since its start; I fear that Galea’s idea of a space free from politics hides a less-than-objective predisposition. It’s meant to claim a specific viewpoint as neutral and true.

I don’t have time to discuss Galea’s book in full. Instead, I’ll point interested readers to a profane, amusing, but deadly serious and detailed takedown in an episode of the Death Panel podcast called “Liberalism, ‘Illiberalism,’ and Public Health.” But one last critique.

Galea has a soft spot in his book for the Great Barrington Declaration, an open letter published by lockdown skeptics in October 2020. He’s fond of it not because, he says, he believes in its assumptions or prescriptions but because the rest of us tried, judged, and convicted the authors in the court of public opinion instead of judging it scientifically. Galea fails to mention that the Great Barrington Declaration was not a scientific manuscript, but a document issued by a right-wing think tank. It was never proposed for scientific review. However, four of us in 2020 tried to address the points covered in the declaration from both a clinical and an epidemiological perspective in The Washington Post. The implications of the Great Barrington Declaration were not academic: They were immediate and dangerous and had the imprimatur of the White House, which included a briefing for President Trump in the Oval Office.

What is going on here? The two Times pieces seem to want to push the idea that Covid in the US wasn’t “that bad” and that the mitigation measures taken were overzealous, likely to have done more harm than good. Galea adds that much of the motivation of public health officials was politically driven. Berliner just wants to both-sides the origin of Covid (a symbol of the false equivalency that he and Galea posit—that ideas should be lifted based on the need for balance rather than any evidentiary requirements).

So much of this, as other writers have said, is about class in America. The Times’ Covid coverage has frequently tilted toward the needs of white and wealthy readers—ones who could sequester away at home or in their country houses during the height of the pandemic, whose kids went to schools with new ventilation systems and Covid testing and for whom the pandemic response was just good enough (we’re not Uganda!). For others like Berliner and Galea, there seems to be a deep need to lean into power in its ascendancy—that is, to show conservatives that they have a friend, with support for the lab leak theory and the Great Barrington Declaration meant trot out their bona fides.

Except this all makes us more vulnerable to the next pandemic, by suggesting that mitigation efforts were overzealous, not supported by the data, did more harm than good, and were “just political,” and that what happened to us was not so bad in terms of international comparisons. And the obsequiousness with which some try to gain the favor of conservatives shows a real misreading of the threats coming for public health from a possible Donald Trump presidency, ongoing attacks on public health at the state and local level, and a willingness to play fast and loose with the data.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →It’s incumbent on those of us in public health to push back against these narratives from the media, from within certain quarters of public health and clinical medicine. Lives depend on it. There is a lot to learn from the past four years, and holding fast to the facts does matter, even if it’s not what some want to hear. With the potential for a new pandemic happening sooner than later, with the specter of H5N1 influenza (“bird flu”) on the horizon, this revisionism needs to be nipped in the bud now.

More from The Nation

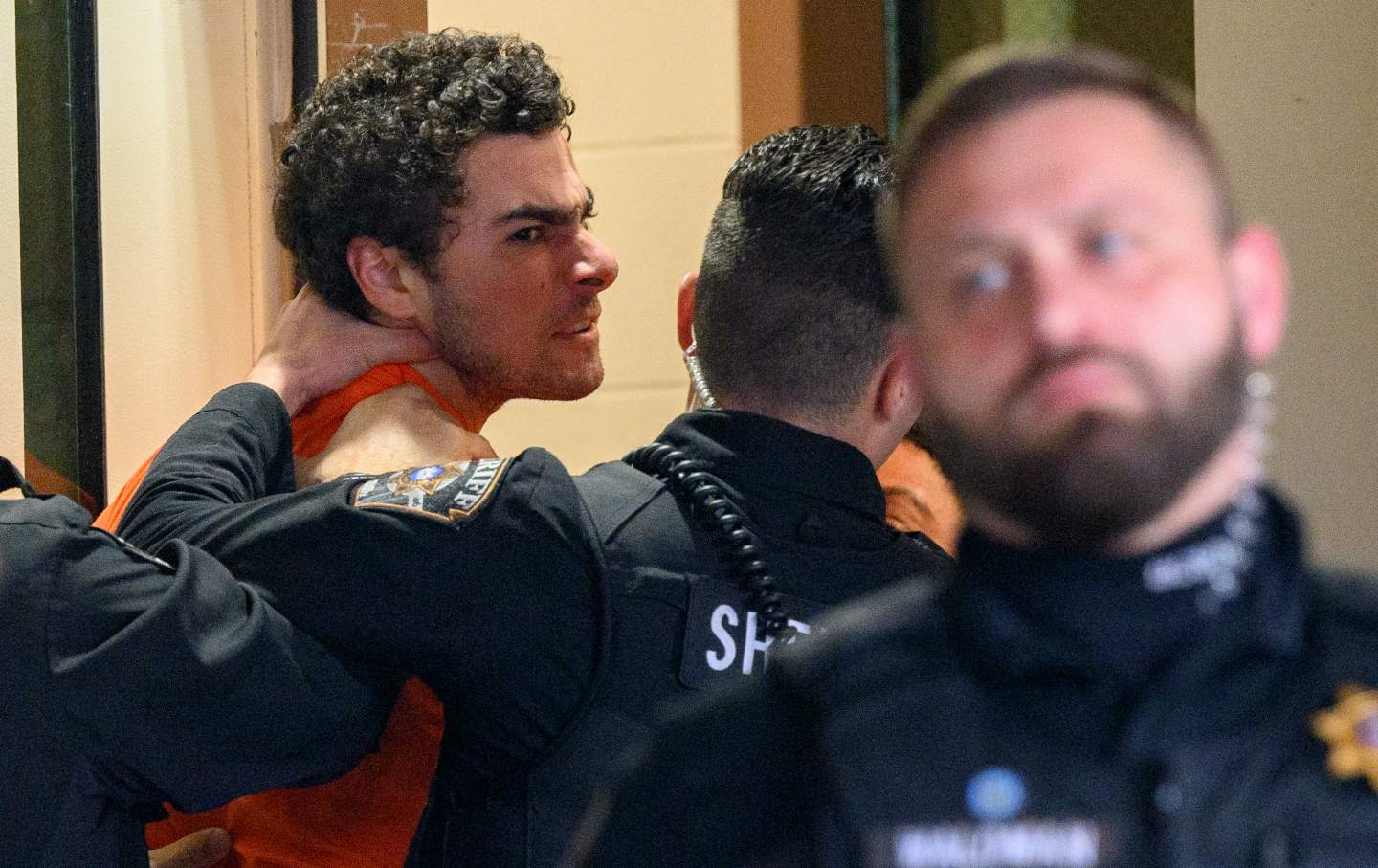

What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America

When social structures corrode, as they are doing now, they trigger desperate deeds like Mangione’s, and rightist vigilantes like Penny.

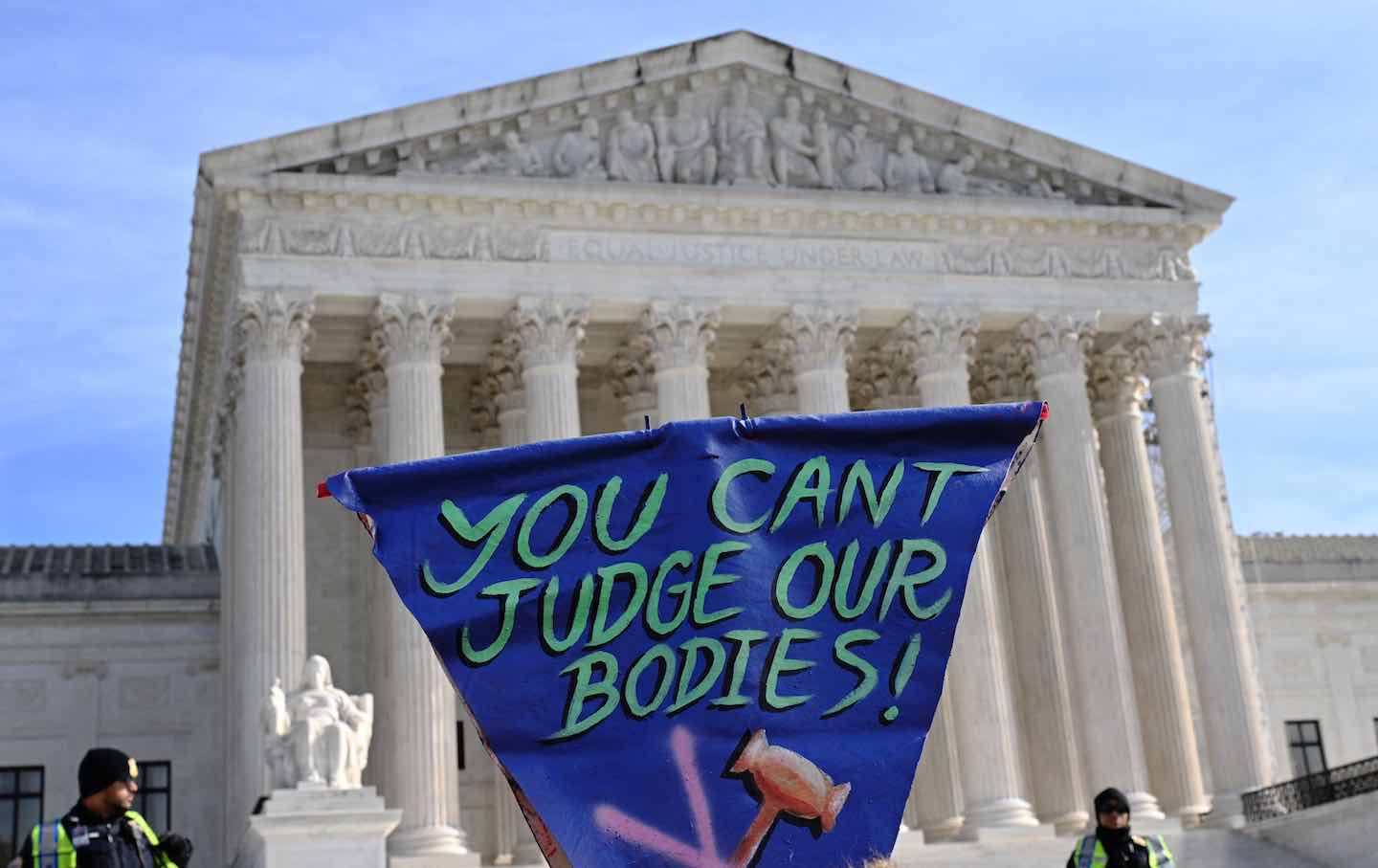

Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm

Contrary to what conservative lawmakers argue, the Supreme Court will increase risks by upholding state bans on gender-affirming care.

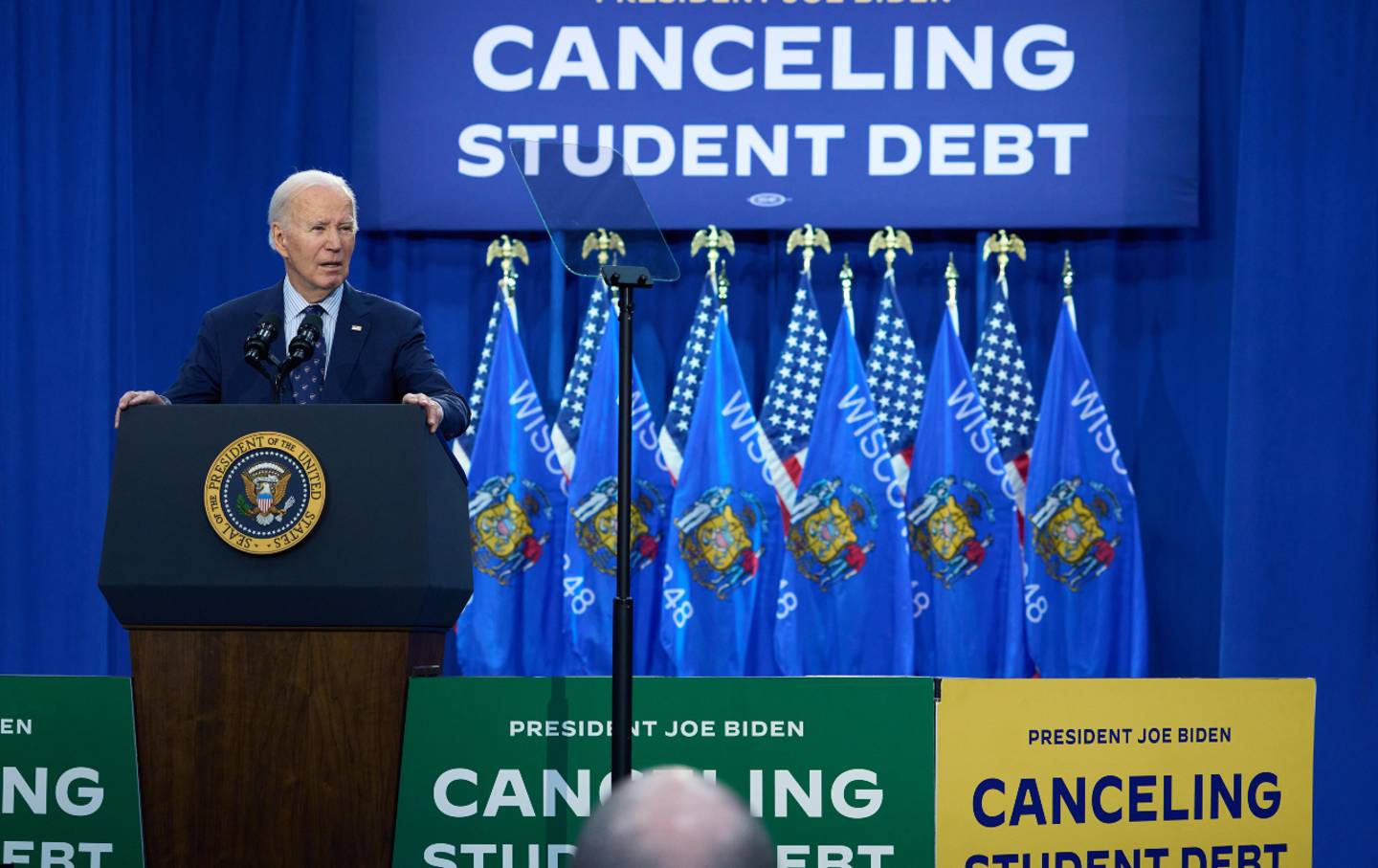

It’s Still Not Too Late for Biden to Deliver Debt Relief It’s Still Not Too Late for Biden to Deliver Debt Relief

Four years after hearing the president promise bold action on student debt, most borrowers are still no better off, and many—especially defrauded debtors—are measurably worse off....

It’s Been a Tough Year. Let’s Help Each Other Out. It’s Been a Tough Year. Let’s Help Each Other Out.

There may be a dark shadow hanging over this year’s holiday season, but there are still ways to give to those in need.

Prison Journalism Is Having a Renaissance. Rahsaan Thomas Is One of Its Champions. Prison Journalism Is Having a Renaissance. Rahsaan Thomas Is One of Its Champions.

Thomas and his colleagues at Empowerment Avenue are subverting the established narrative that prisoners are only subjects or sources, never authors of their own experience.

Luigi Mangione Is America Whether We Like It or Not Luigi Mangione Is America Whether We Like It or Not

While very few Americans would sincerely advocate killing insurance executives, tens of millions have likely joked that they want to. There’s a clear reason why.