How Capitalism Disordered Our Eating

From Weight Watchers to Ozempic, big business profits off eating disorders and their treatments.

Metaphors for the body abound: a many-horse-powered machine, a delicate ecosystem, a knife-cut sculpture. Eating disorders might skirt the body’s regular rules, but they’re still invested in symmetry and measurements, engineering; the body reimagined as a race car instead of a sensible sedan. Built for speed, stares, grinding to a sudden halt and burning up, sparking gasps.

At first, the hum. A nicotine head high, a purring engine. The numbers going down, the compliments adding up

Eating disorder deaths often happen frighteningly fast, symptoms spiking outside the expected trajectory, bodies rejecting their places on a graph. Eating disorders kill in a variety of ways, despite the image in your mind’s eye: an emaciated girl in a billowing hospital gown, perhaps. In reality, one of the most common causes of death related to eating disorders—although least reported on—is one that takes place when the person is supposedly in recovery. There are rafts of studies on “sudden death” in eating disorder patients. In medical terminology, “sudden death” is defined as an “abrupt and unexpected occurrence of fatality” with no obvious proximate explanation.

About one-third of anorexia deaths are coded as sudden death. Eroding the organs–whether by starvation, laxative abuse, or purging—can cause the heart to skid to a halt in a surprising number of ways. Electrolyte imbalances from purging induce seizures. Gastric rupture occurs between a binge and a purge, when the stomach or intestines burst, leading quickly to necrosis, septic shock, and death. Autopsies carried out on eating disorder patients who died sudden deaths report gut renovations of the body’s core systems, complete rewirings that allowed the body to run faster on far less fuel but came with a high cost to engine life. These documents call this phenomenon “starvation-derived anatomical remodeling of the heart.”

There is a parallel between our attempts to anatomically remodel ourselves into a physically impossible ideal with the capitalistic attempt to entirely remodel the individual into the perfect, productive worker. Both attempts are murderous, and occurring under the cover of moralizing, medicalizing rhetoric. But this is where the metaphors start to break down, which is also the point. We try to adopt a life hack that is also a self-harm practice. The wanting and wasting, boom and bust, binge and purge, expansion and recession. And then the artificial stimulus, the Fed printing money: pills and supplements and powders. We want what we were sold: resets, reinventions, and bailouts.

But the body eventually belies the calorie-counting ethic we’ve been taught, revealing that it is not, in fact, an economic model that can simply be erased, written anew on a fresh whiteboard, and solved for again.

In a society defined by obsessions with both consumption and self-discipline, not to mention self-surveillance, eating has transformed into a math problem and a performance. As the war on obesity met foodie culture, we learned to photograph and post our meals as well as our workout regimens, and eating disorders became ever more prevalent. Is it any wonder we’ve replicated our country’s consumptive contradictions and crises within our own borders, in our bodies?

Bulimia was introduced to the DSM in 1980, the beginning of the “greed decade” that brought us neoliberalism, fast money, Wall Street scams, shopaholism, the “low-fat lie,” the fanaticism for fitness magazines and aerobics, and easy access to bingeable, ultra-processed foods. Extreme diets, anorexic troughs are recessions, an orientation toward austerity: 2008 was both the peak of the Great Recession and the high point of aughts tabloid coverage of starlet skinniness, not to mention the peak of the pro-anorexia Tumblrverse. What followed the aughts’ anorexic aesthetic were the twenty-teens, a decade of grifters and start-up founders lying through their teeth and almost getting away with it, and it was also an era of girls sticking their heads in toilets and exiting bathrooms with minty breath, lying as confidently as any con man.I don’t think I am listing coincidences. Like the start-up billionaires torpedoing their own companies, we were girls heading toward a crash. Like most disruptive technology, the eating disordered person’s full-system reboot has a dark underside. Endless consumption overfills landfills; toxic chemicals leach into groundwater. The seas rise and flood cities. Eventually, we break down, break bones, and break our own hearts.

Girls have long been medical guinea pigs, and our experience as eating disorder patients is just one chapter in a story that starts before the lobotomies and continues today with dangerous experimental weight loss drugs and eating disorder treatments. As an illness class, eating disorders can be understood as guinea pigs for the post-1980 model of mental health care, one aligned with the biological model of mental illness and neoliberal economics. That experiment can almost categorically be deemed a failure, one that turned us into sacrificial lambs.

Eating disorders were first recognized as an epidemic issue in the same decades that market-oriented reforms were remaking Western economies, ushering in the modern era of opaque globalized financial systems, heightening inequality, cyclical economic crises, and consumer capitalism. In 1984, Fredric Jameson published Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, outlining the restructuring of contemporary life around commodification and consumption, and the International Journal of Eating Disorders published a paper investigating the suddenly “widespread” bulimic psyche. The third edition of the DSM had thudded onto doctors’ desks in 1980, heavier than earlier editions. The first two were slim tomes outlining diagnoses in broad strokes, designed to help psychiatric professionals describe their patients’ suffering in the hopes of discovering its underlying, unconscious sources. The third edition heralded a transformation in mental health diagnosis and treatment, a reconception of diagnosis as a concrete taxonomic endeavor. Less an art of description than a process of elimination through checklist—part of the larger reordering of life around counting and calculations, data-based self-surveillance oriented toward optimization.

The new DSM was also part of an effort to create a guidebook for psychiatrists akin to the diagnostic manuals used by physical doctors. Doctor and writer Laura Kolbe describes those as tools for “cognitive rationing and cognitive investment banking” by a medical establishment beset by overworked doctors and overcrowded hospitals. With economic terminology already infecting the way doctors conceived of their time and energy, cognitive rationing quickly became care rationing. During the prior decade, the Nixon administration had aimed to cut skyrocketing healthcare costs by replacing individualized care rooted in long-term doctor-patient relationships with data-driven, widely applicable techniques that could be replicated by any doctor, with any patient. The rise of “evidence-based treatment,” considered cost-effective because it had been studied in large-scale trials, meant that randomized controlled trials replaced individual case studies as the gold standard of psychiatric research.

These turns ushered in an utter transformation in the treatment of all mental disorders, but they uniquely affected eating disorder care because of their timing: right when eating disorders were first widely recognized and standardized, treatments developed. That 1980 DSM was the first to include a stand-alone eating disorder category. As Lester writes, the “shift in the DSM in the 1980s to a more descriptive mode of diagnosis (versus an etiological or interpretive one) emerged hand in hand with economic transitions in healthcare funding that focused on increased efficiency and cost savings and were based on outcomes that could be quantified,” so psychic suffering was reframed “as collections of cognitive, behavioral, or biological symptoms that could be objectively measured.” This set the stage for a collusive cycle between psychiatry and insurance, transforming a person who was once a patient into a math problem meant to be solved using economic formulas.

Throughout the ’90s, for-profit insurance companies and health maintenance organizations—which had emerged in the wake of the Nixon administration’s passage of the Health Maintenance Organization Act, introducing “the concept of for-profit healthcare corporations to an industry long dominated by a not-for-profit” model, according to the National Council on Disability—were consolidated by investment firms. Today over half of the most popular plans are owned by such firms. Profit-driven insurance companies want to pay for proven investments, and it is difficult to prove the efficacy of an extended, intimate relationship between patient and therapist. The demands of insurance rendered the relationship between psychiatrist and patient episodic, transactional, and pharmacological, when it was once long and emotional.

The “chemical imbalance ” theory of mental illness—the notion that a deficit of certain neurotransmitters in the brain causes mental illness had been outlined in The American Journal of Psychiatry in 1965, and it was soon adopted and endorsed by much of the psychiatric community. Credited for reducing the stigma of mental illness, the theory ostensibly deflected shame from the patient, blaming biology instead of personality, and reframed the diseases as treatable with medication. As of 2016, over half of American psychiatrists had stopped practicing psychotherapy completely, opting instead for medication management. Within this scarcity economy, cognitive behavioral therapy has become one of psychiatry’s favorite non-pharmaceutical tools. Aaron Beck wrote the first CBT manual in 1979, arguing that many mental illnesses were not mood disorders but cognitive ones, which he proposed to treat with a universally applicable, systematized protocol provided through a fixed number of standardized, time-limited modules. These teach patients which thoughts are “productive” and “unproductive” and how to replace the latter with the former, according to popular online explainers and CBT handbooks. CBT quickly became the “favorite choice” for companies “looking for cost-effective alternatives to traditional psychotherapy,” according to Evidence Based Mental Health. Elsewhere, Cognitive Therapy and Research reported that “despite the enormous literature base, there is still a clear need for high-quality studies examining the efficacy of CBT,” which “is questionable.” In his book CBT: The Cognitive Behavioural Tsunami, Farhad Dalal argues that CBT upholds a “managerialist mentality” that prizes notions of health rooted in potential productivity. Unsurprisingly, many companies offer CBT to employees, which one provider explained is a smart investment, as “untreated mental health issues can drive costs related to productivity.” CBT is “perfectly suited to capitalism,” as P. E. Moskowitz writes, because “it doesn’t ask you to challenge your place in the world or how you think of things, it just asks you to modify your response.” Under this model, the thin, cisgendered, white, straight patient might be free of stigma and thrilled with their Lexapro prescription and CBT exercises, but it is not shocking, then, that a paper on CBT’s efficacy also pointed out that “no meta-analytic studies of CBT have been reported on specific subgroups, such as ethnic minorities and low income samples,” groups whose psychic struggles under capitalism are difficult to solve with positive thinking.

“If bulimia was the eating disorder of Reaganomics and millennial girlbossery, and anorexia was the eating disorder of aughts-era austerity, these drugs might foster an eating disorder for a new age of technocapitalism.”

While the American Psychiatric Association’s recommendations for treating eating disorders include a range of therapies (including nutritional counseling and psychotherapy), CBT is reliably listed near the top of its suggested treatments for bulimia (paired with antidepressants), binge eating disorder (paired with psychiatric medication), and anorexia. These techniques are considered first-line treatments, according to a 2017 Physiology & Behavior analysis, despite the fact that the same study concluded that “there have been only a few attempts to test the cognitive behavioral theory of eating disorders,” the majority of which have not reported positive results-one found a 44 percent rate of relapse just four months after treatment.

Aside from CBT, pharmacological treatment and genetic etiologies are well-trod realms of eating disorder research. Despite plying patients with everything from SSRIs to antipsychotics and stimulants, researchers have yet to find a drug that reliably helps most patients. The reams of research devoted to genetic studies have thus far mainly revealed that a person is more likely to develop an eating disorder if a parent or sibling has one, a finding that can just as easily be attributed to household environment as genetics. As Dr. Howard Steiger has written, genetic explanations can “relieve blame ” and stigma from the patient, but such shame could just as easily be reduced by externalizing blame on to not chemical imbalances or genes but the misogynistic white supremacist society the patient grew up in, though in that scenario they may not remain a lifelong customer of the mental healthcare system.

Some experts are attempting to question our reigning ineffective treatment models and the disease etiologies they rest on. But while these figures recognize that eating disorders are complicated biopsychosocial illnesses, the result of an interplay between environment and genetics that must be analyzed from many angles, most are still resistant to centering cultural explanations in eating disorder scholarship, unwilling to accept the slim ideal’s pivotal role in the disease. Doing so would destabilize the biological model of mental illness and demonstrate that eating disorders may not be curable with behavioral thought exercises and pharmaceuticals—a revelation that would cost a lot of parties a lot of money. The same parties, incidentally, that are funding many of the studies into those etiologies and treatments, while public institutions neglect eating disorders. One report from World Psychiatry called eating disorders the illnesses with funding “most discrepant from the burden of illness”: Federal funding was $0.73 per ill person in 2015, compared with $86.97 per person with schizophrenia, for example.

Meanwhile, eating disorder treatment is understood by business publications like Forbes, TechCrunch, and PE Hub as a growth market. PE Hub called treatment centers one way to satiate investors’ “appetite for high growth scale assets,” an opportunity private equity and venture capital firms have seized, buying up centers and rapidly expanding stand-alone ones into chains. None of this growth has been at all constrained by the fact that mortality rates have remained stable and high through it all, implying that the treatments aren’t working, or the fact that a 2016 editorial by a group of concerned eating disorder doctors calling for “transparency” from private centers reported that equity-backed treatment centers provide scarce, if any, data on their outcomes and often offer treatments with “no documented utility.”

Reflecting larger macroeconomic trends, one of the biggest treatment conglomerates, Monte Nido, received investment money from a venture firm in 2012, after which it tripled in size and was resold. Its facilities have since been reviewed as “very very bad” and “very poorly run with poorly trained staff” by former patients and as “unsupportive, unsafe,” and “understaffed” by former employees. One former employee of a treatment chain, which is part of a conglomerate that also treats other mental disorders, said the company moved staff across wards, sending people “without any training in eating disorders” to eating disorder units to cut costs. They said their program’s wait list “was always bursting, so there was a lot of just cycling [patients] through.” Data-driven standardization leading to decreased quality of care is an unsurprising result of investment-funded expansion: one survey given to investors found that up to 85 percent ranked the “public health impact” of an investment as “not at all or somewhat important.” Eating disorder doctors writing in Psychiatric Services have pointed out that the corpus of peer-reviewed literature includes “very little” collected from residential centers. At the time of a 2020 review, fewer than 20 peer-reviewed studies had been published on them, most of which lacked controls and half of which had no follow-ups. But investment firms have an even stronger thirst for profit than insurance companies, combined with a less risk-averse ethic. They fund the people who move fast and break things, which in the realm of healthcare can be bodies.

Recently, I saw an ad on Instagram for a “medication-assisted weight loss” start-up, encouraging me to “Learn More” about a drug to induce “weight loss…powered by medicine,” and prescribed via video chat.

The company is part of another boom sector for investors: the telehealth industry. Venture capital firms pumped $29.1 billion into online mental health platforms in 2021, nearly doubling their previously record breaking 2020 investment. According to a report published on the APA’s website, these interventions target conditions “including anxiety, depression, insomnia…and a number aim to…improve well-being through mindfulness, meditation, and weight loss.” The APA’s inclusion of weight loss in an article about mental health care implies that dieting can be mental health care, implicitly buying into the fatphobia undergirding many eating disorders. Another article highlights a virtual eating disorder treatment program that has received millions in funding from firms including the Chernin Group, Tiger Global, General Catalyst, and Optum Ventures. Those firms are also invested in yet another overlapping growth market, currently projected to balloon to $725.6 billion by 2032: the weight loss market, which includes the app I encountered. Optum Ventures, Tiger Global, and General Catalyst are all also invested in addiction treatments. Other than eating disorders, addiction is the only mental illness almost exclusively treated in residential centers as expensive as they are ineffective, and therefore profitable for the investors counting on a growing population of lifelong repeat customers from both epidemics. One study found that 59 percent of patients discharged from addiction treatment for opioids relapsed within a week. The average cost of a stay in these centers sat at close to $10,000 in 2022. As a 2023 article in Marketplace put it, addiction treatment is “now seen as a big moneymaker.”

That the same firms are funding eating disorder treatment, addiction treatment, and weight loss start-ups underscores the fact that these aren’t just disturbingly intertwined industries but interrelated gears of one larger economy that profits off pain. The treatment industry, though perhaps not purposely, is currently functioning along an economic model parallel to the weight loss industry’s, creating patient-customers who cycle in and out of treatment for decades. A leaked Weight Watchers business plan explicitly stated the company’s reliance on its product’s failure, which transforms dieters into lifelong customers: Weight Watchers members return to the program on average four times—that’s “where your business comes from,” according to the former CEO. Few treatment facilities publish their readmission rates, but the ones that do suggest that about 45 to 77 percent of their patients are readmitted. They tell the same story as weight loss companies in more mournful terms, emphasizing the disease’s tragic intractability rather than their failing methods. Meanwhile, patients have reported staying in residential facilities more than 10 times in a lifetime of disease, and mortgaging homes or accruing tens of thousands of dollars of debt to pay for it.

Weight loss companies inevitably drive some of their customers into disordered eating (a NEDA survey of college students found that 35 percent of diets become “pathological” and up to 25 percent of them “progress” into eating disorders). Once those customers are sick, they might turn to a treatment program that unbeknownst to them is funded by the very same firms funding the weight loss app that led them down this path in the first place. Weight loss companies, in effect, produce customers for eating disorder treatment companies. This is not to say that investors are conspiring to sicken people, but that they have no incentive to invest in treatment that works, or disinvest in treatment that creates lifelong customers for multiple products they are invested in.

On Instagram, where even our dreams get filtered, the squares are filled with beautiful women eating junk food. There is an account called You Did Not Eat That, which calls out women for posing with food the account owner does not believe they actually ate, based on the size and shape of their bodies.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The accused liars are acrobats, attempting to perform the conspicuous consumption our culture encourages while staying small. They are economists, calculating the hours of exercise required to cancel out what they ate, and chemists, mixing pills and powders to flush everything out. Our economy besieges us with dueling imperatives, imploring us to indulge and then preaching restriction. Charts and graphs proliferate, listing “low-calorie high-volume foods” dieters can eat in large quantities.

Twenty-first-century food systems encourage bingeing alongside restriction and purgative restarts. We are expected to engage in bodily self-management, so those who eat along the exact lines the food system encourages end up demonized when they are fat. The rise in obesity has been tracked and correlated with the pivot toward highly processed food–– these changes to our food systems, and, in turn, our economy, can also be traced over the peaks and valleys of the eating disorder epidemic.

A bulimic describes their process as eating something unhealthy, safe in the knowledge that they are gonna go to the bathroom right afterward to erase it. This erasure is at the core of all bulimic behavior, and the impulse to binge that precedes it is provoked by our food systems, our algorithms, and our culture of dieting. Under the cover of late-night dark, we can binge shop online, binge whole seasons of a TV show, swallow thousands of calories, and then change our minds, print a return label, refresh the browser, take a pill, and pretend it never happened.

Lately, Big Pharma has a different fantasy to sell us, a syringe of chemicals that won’t allow us to eat without getting fat, but promises to suck the yearning to consume right out of us instead. Riding the subway recently, I sat in a car covered in photographs of women holding syringes. Bands of abdominal flesh pinched between manicured fingers, syringes pricking skin. The words “a weekly shot to lose weight” floating above it all, and an invitation: “download.” The ads were for an app that prescribes Wegovy and Ozempic, the injectable weight loss drugs approved by the FDA in 2021, which function by disrupting the body’s natural insulin production and slowing digestion, suppressing hunger and inciting extreme nausea if someone taking the drug eats even a normal-sized meal, according to many patients. These drugs are currently projected to make their manufacturers billions and change the face of the weight loss industry, according to Bloomberg and Forbes, despite scant long-term research, alarming side effects, and the fact that patients who come off the drugs report rapidly regaining lost weight. The ads I saw were for a company funded in part by General Catalyst and the Chernin Group, both also funders of an eating disorder e-therapy, and, in GC’s case, Mindstrong and an addiction e-treatment too.

If I logged on to one of these sites, as New Yorker journalist Jia Tolentino did in her reporting on these drugs, I would be prompted to enter my height and weight, be paired with a prescribing doctor who would speak to me via virtual chat, and, after a few minutes and more than a few hundred dollars, have vials and syringes mailed to my apartment. To see if the drugs were accessible to people not deemed overweight, Tolentino joined the app and easily received a prescription (in the article, Tolentino describes herself as wearing a size 4). She didn’t take the drugs, writing that they seemed like an “injectable eating disorder.” I’d agree, and I’d argue that they will also act as steroid injections into existing eating disorders, as ads like the ones I saw and these drugs’ accessibility render it terrifyingly likely they will be prescribed to people with eating disorders, especially the majority of disordered eaters who do not present as underweight.

If bulimia was the eating disorder of Reaganomics and millennial girlbossery, and anorexia was the eating disorder of aughts-era austerity, these drugs might foster an eating disorder for a new age of technocapitalism, wherein we try to recast hunger as just another inconvenience we can eliminate with an app. Of fat people who have struggled with self-love, a plastic surgeon told Tolentino that “they’re no longer going to accept that they should just be happy with the body they have,” and will instead be able to buy and inject their way to the one they want, fatness rendered just another archaic fossil, as outmoded as the corded phone. Never mind if Ozempic costs us our enjoyment of food or causes cancer (after being told that these drugs have been proven to cause thyroid cancer in rodents, someone taking Ozempic told New York, “I’m like, Thyroid cancer’s not that bad?”), or if all our bodies start to lose their unique forms and look ever more alike.

The futurists running these companies promise us a frictionless existence, free of life’s inconveniences. According to an online explainer on the role of friction in physics, without it, “it would be very difficult for people or cars to get moving or change direction.” Do we want to keep traveling in the direction Big Tech and Big Pharma have been leading us? What these drugs offer isn’t a full life but one lived in the uncanny valley, where appetite is an outdated relic of a less evolved era. Their boosters want us to imagine that future as unencumbered, but I’m worried that if we unburden ourselves of our drives, we’ll end up empty inside. That frictionless existence will be lethargic and lonely; we ’ll be Barbies entrapped in plastic packaging. Disorientingly numb, with a bit of mild nausea: the body’s muffied scream, a reminder that you aren’t an iPhone-enabled avatar but an animal meant to eat and shout and fuck and even be inconvenienced sometimes by something you can laugh at over a meal with a friend whose body looks unlike yours.

By offering to untether us from our urge to nourish ourselves, the technocapitalists are effectively offering to turn down the volume on our will to live. All that to bring us closer to the slim ideal that has been sickening us all along, and is what, in a better world, would actually be a relic of a less evolved era. Injections of cash from investors, injections of chemicals from corporations, injections of thin fetishism straight into girls’ arteries. Weight cycling and eating disorders alike cause heart attacks, yet we’re feeding coin after coin into the pinball machine, sending girls ricocheting between diets and drugs and diseases. The flashing lights are distracting, just like the artistically shot advertisements, but they’re all versions of the same old sold-out show, which is one we’ve seen before, where the girl ends up beautiful and dead. Capitalism and the thin ideal are shapeshifters: Silicon Valley rose from the ashes of the 2008 recession, the wellness boom brought us orthorexia, and Ozempic and buccal fat removal stole the stage back from body positivity. The stock market rebounds, and the eating disorder numbers tick ever upward. The men in suits continue counting cash.

More from The Nation

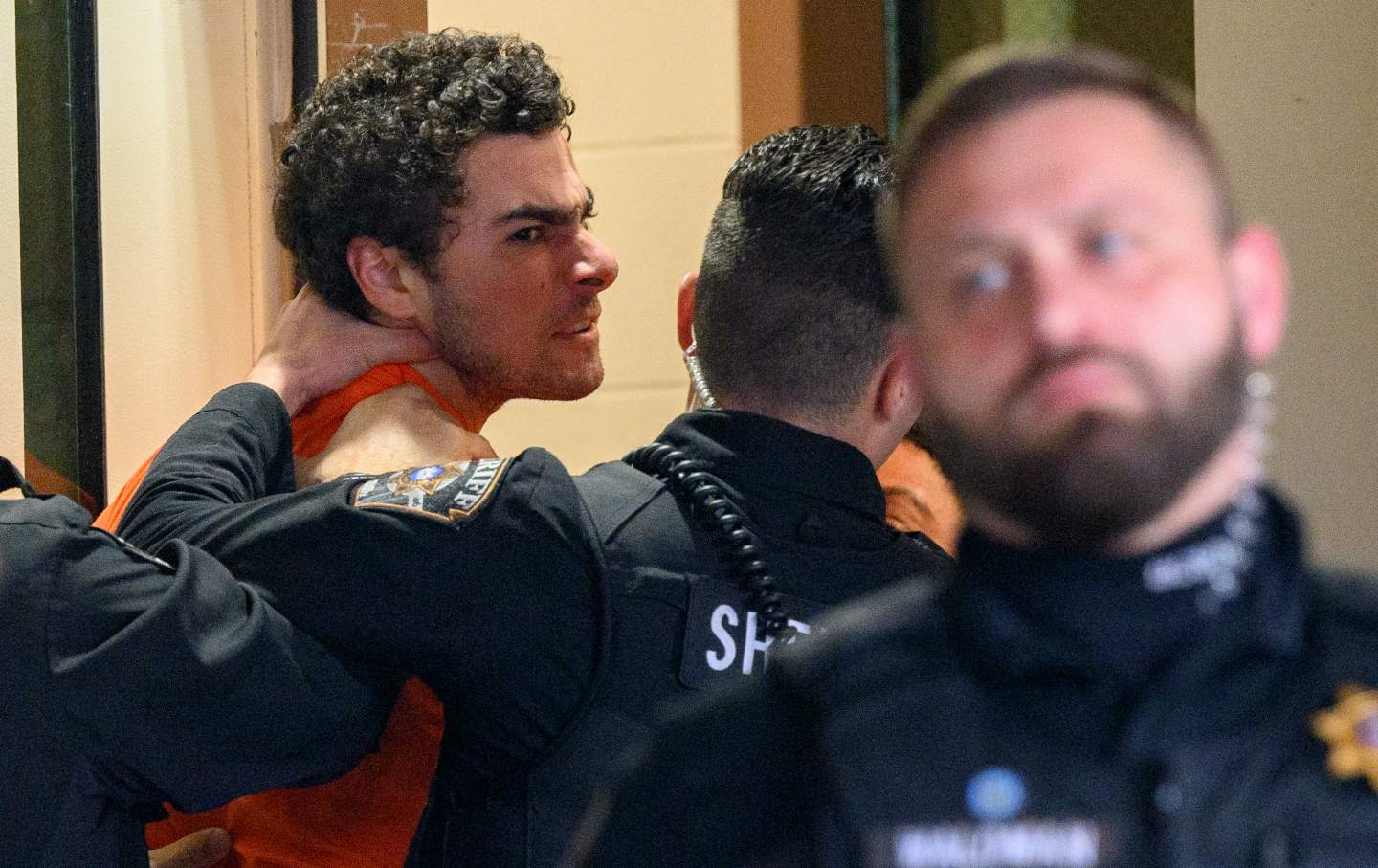

What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America

When social structures corrode, as they are doing now, they trigger desperate deeds like Mangione’s, and rightist vigilantes like Penny.

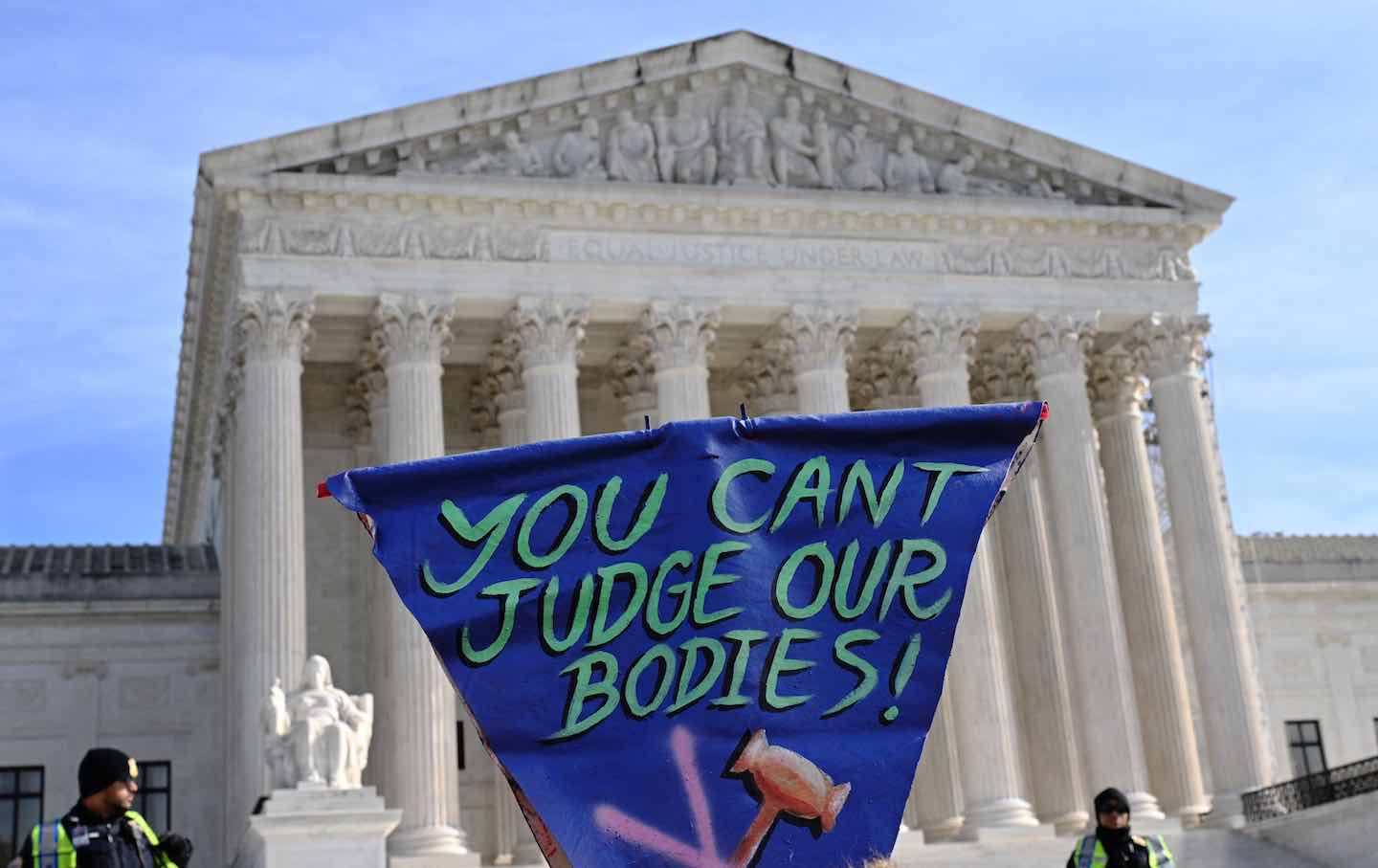

Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm

Contrary to what conservative lawmakers argue, the Supreme Court will increase risks by upholding state bans on gender-affirming care.

It’s Still Not Too Late for Biden to Deliver Debt Relief It’s Still Not Too Late for Biden to Deliver Debt Relief

Four years after hearing the president promise bold action on student debt, most borrowers are still no better off, and many—especially defrauded debtors—are measurably worse off....

It’s Been a Tough Year. Let’s Help Each Other Out. It’s Been a Tough Year. Let’s Help Each Other Out.

There may be a dark shadow hanging over this year’s holiday season, but there are still ways to give to those in need.

Prison Journalism Is Having a Renaissance. Rahsaan Thomas Is One of Its Champions. Prison Journalism Is Having a Renaissance. Rahsaan Thomas Is One of Its Champions.

Thomas and his colleagues at Empowerment Avenue are subverting the established narrative that prisoners are only subjects or sources, never authors of their own experience.

Luigi Mangione Is America Whether We Like It or Not Luigi Mangione Is America Whether We Like It or Not

While very few Americans would sincerely advocate killing insurance executives, tens of millions have likely joked that they want to. There’s a clear reason why.