Not a single significant policy or initiative proposed by the candidates for the Democratic presidential nomination is likely to survive a Supreme Court review. Nothing on guns, nothing on climate, nothing on health care—nothing survives the conservative majority on today’s court. Democrats can win the White House with a huge popular mandate, take back the Senate, and nuke the filibuster, but Chief Justice John Roberts and his four associates will still be waiting for them.

If the Democratic candidates are serious about advancing their agenda—be it a progressive agenda or a center-left agenda or a billionaire’s agenda—then they have to be serious about undertaking major, structural Supreme Court reform. That reform is not airy wish-casting by a hard left dreaming of revolution. It is the practical first step toward getting any meaningful Democratic policies through all three branches of government. Either court reform happens or nothing happens. People who focus only on Congress or the presidency are like people who plan a road trip thinking only about their eventual destination. They forget that without gas, nobody is going anywhere.

Court reform can take a variety of forms, some blunt and partisan, others intricate and geared toward balance. But at its core, Supreme Court reform involves shaking up the configuration of the court. And at its core, it is constitutional. That’s because the Constitution provides Congress with wide latitude in structuring the court.

The Supreme Court (and all federal courts) are established by Article III of the Constitution. And Article III has only this to say about the structure of the Supreme Court:

The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour, and shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services, a Compensation, which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office.

That is founding-father-speak for “Whatever. We’ll figure this part out later.”

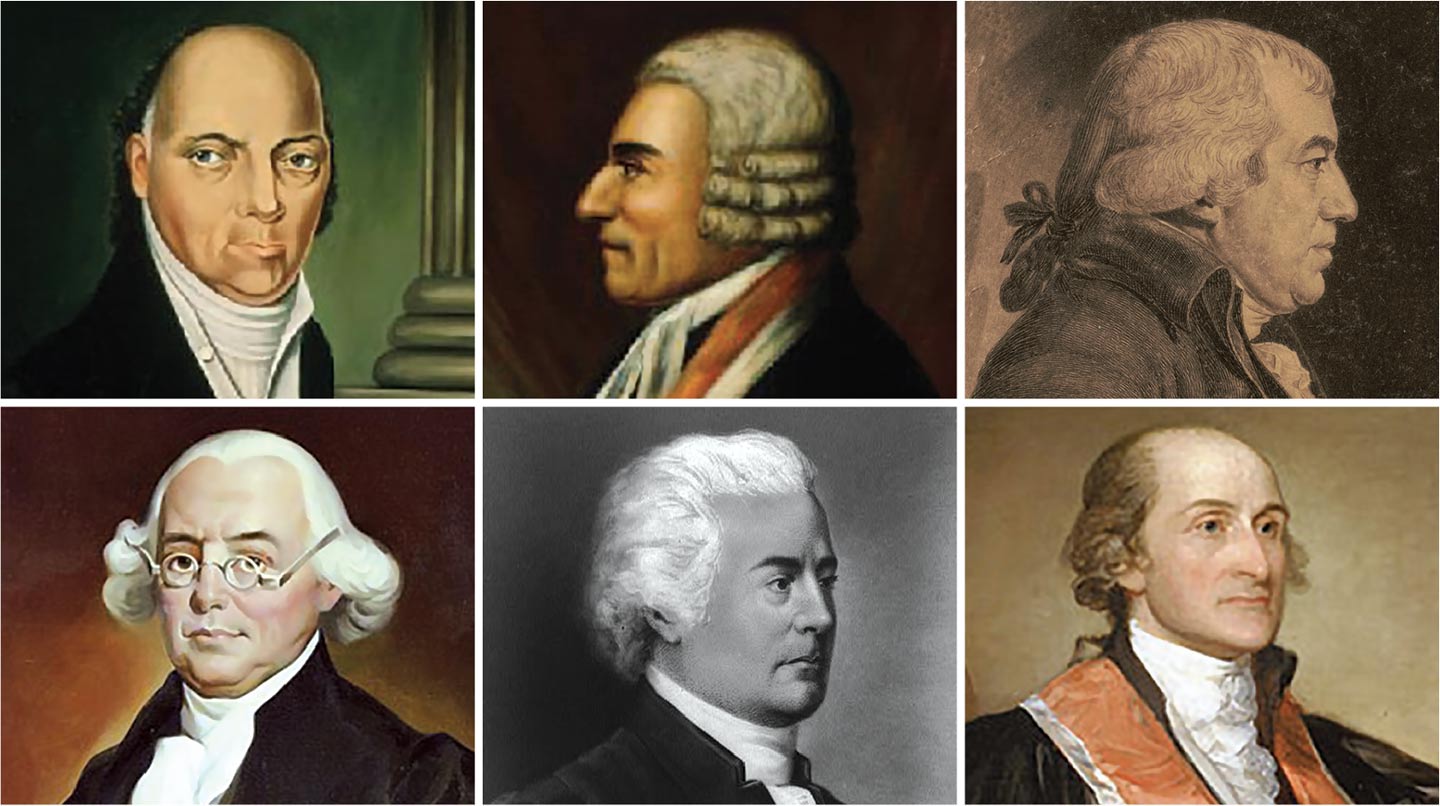

In fact, it took the country a long time to figure out how to structure the Supreme Court. The first version of the court had six justices. John Adams and his congressional allies changed that number to five in the months after his loss to Thomas Jefferson to prevent him from filling a judicial seat. Jefferson quickly repealed that law, putting the number back to six, and later added a seventh justice, because why not? Andrew Jackson pushed the court to nine justices; Congress added a 10th during the Civil War and then pulled it back to seven in 1866 as payback to President Andrew Johnson for, among other things, vetoing the Reconstruction Acts. Then everybody got over themselves. The current number of nine justices has been set since the Judiciary Act of 1869.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

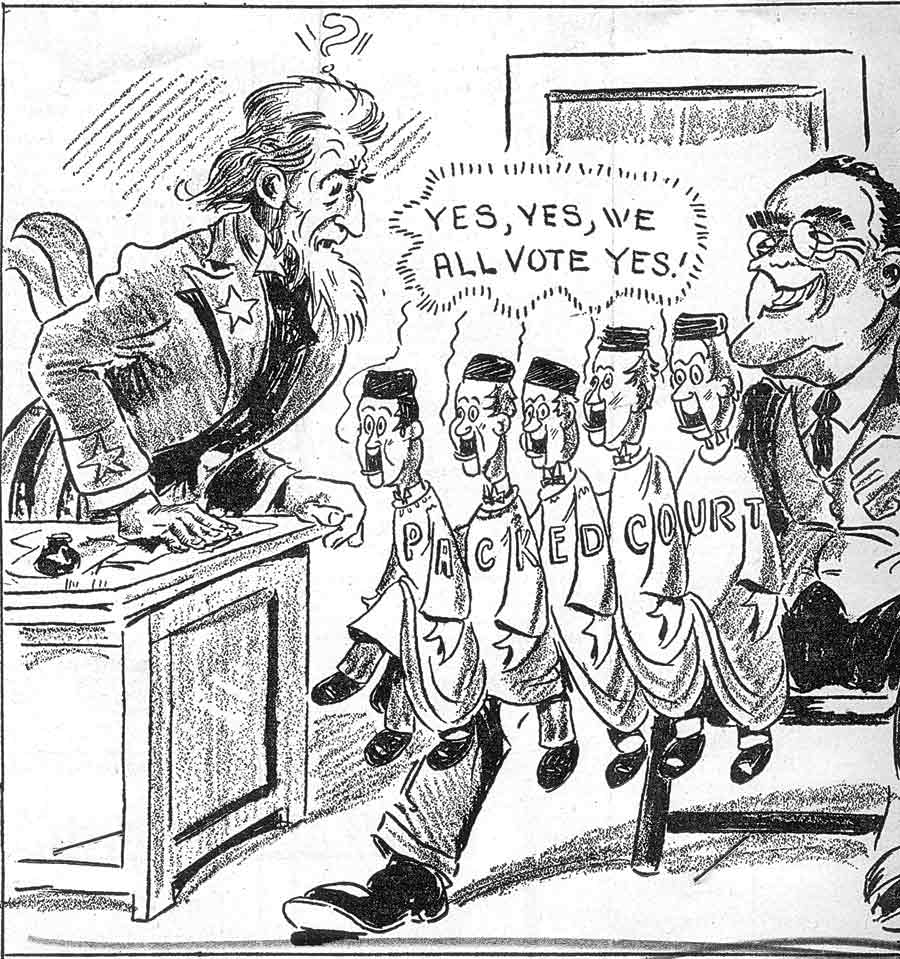

Only one serious effort to change the number of justices has been made since then, and most people have heard about it. Frustrated by a court that stood against his New Deal programs, Franklin Roosevelt proposed the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937. It would have allowed him to appoint up to six new justices to the court, for a total of 15. Democrats and Republicans alike opposed the bill, and it failed miserably. Between the unpopular proposal and an economic downturn, the Democrats hemorrhaged seats in the midterm elections of 1938. In the ensuing decades, nobody seriously attempted to futz with the Supreme Court again.

Until Mitch McConnell came along.

After Justice Antonin Scalia died in February of 2016, majority leader McConnell and the Senate Republicans unilaterally decided to change the number of Supreme Court justices from nine to eight for the remainder of President Barack Obama’s term. It was a scheme every bit as cynical and partisan as what Adams had tried to do to Jefferson, only McConnell’s gambit worked.

One year later, with the help of President Donald Trump, McConnell was able to replace Scalia with Neil Gorsuch. Then, to spike the football, Trump and McConnell responded to the retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy (a swing voter on the court) by installing a hard-core conservative who was accused of attempted rape, Brett Kavanaugh. We’re now looking at a Supreme Court staffed for a generation with an illegitimate justice and a morally repugnant one.

Because of McConnell’s brazen maneuvers, court reform is suddenly back in vogue. Many of the Democratic presidential candidates have indicated an openness to the idea, while scholars and think tanks are pumping out reform proposals. Some of these favor reform in its rawest, tit-for-tat form: packing the court with two new justices to make up for what McConnell pulled with Gorsuch and Kavanaugh. But the idea of court reform is much broader, more nuanced, and frankly less partisan than what both proponents and detractors of court packing may imagine. There are proposals focused on changing how we choose Supreme Court justices. There are proposals centered on limiting the lifetime power of justices. There are proposals that seek to make the Supreme Court work more like every other federal court. And there are proposals addressing judicial ethics and the simple and noble goal of keeping people who have been credibly accused of sexual misconduct off the highest court in the land.

Some or all of these proposals can work. While reforming the Supreme Court is a legal issue—a number of the plans raise real constitutional questions—it is also, perhaps even primarily, a political issue. As Sean McElwee, the director of research and polling for the reform group Take Back the Court, told Politico, “We have too long tried to take on the court with the tools of law, but if the court is in fact a political branch, then instead of using the tools of law, you need to use the tools of politics.”

The public can be motivated on this issue, but it needs to understand that the fight is not for a Democratic Party Court but a functional one. Court reform is not a revenge fantasy; it is an attempt to restore the Supreme Court to legitimacy and fairness.

There are now three main ideas for reforming the court: adding moderates to its bench, imposing de facto term limits, and enlarging it with more ideologically diverse justices who are bound to ethical guidelines.

Let’s define what those ideas actually mean and stop allowing Republicans to define them for us.

Mandated Moderation

Among the Democrats running for president, former South Bend mayor Pete Buttigieg has stood out as the only contender who has embraced a specific court reform plan. Other candidates, like Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, have indicated that they are open to the idea. Some candidates, like former vice president Joe Biden, simply promise to nominate better judges. But Buttigieg has made court reform a signature part of his campaign.

His court reform plan, colloquially dubbed 5-5-5, is largely cribbed from a Yale Law Journal feature, “How to Save the Supreme Court,” by law professors Daniel Epps and Ganesh Sitaraman (who is a senior adviser to Warren). The core of the proposal is to expand the Supreme Court to 15 justices: five conservatives, five liberals, and five moderates, with each of the last group chosen by a vote of the 10 partisan justices. The 10 partisans would have traditional lifetime tenure. But the moderates, called visiting justices, would serve one-year terms, would be selected two years in advance, and would be chosen from the existing crop of Circuit Court of Appeals or District Court judges. Should the 10 partisan justices fail to agree on a moderate slate, the Supreme Court would lack a quorum and be unable to hear cases that year. As Epps and Sitaraman explain, a key point of this plan is to decrease the partisanship and rancor that now surrounds the Supreme Court:

Finally, the visiting Justices—and the explicit partisan-balance requirements—would significantly reduce the stakes of Supreme Court nominations. Because each political party would hold a set number of seats, and because additional Justices would join the Court no matter what, the fate of issues like abortion would never turn on any one confirmation battle.

Buttigieg understands this challenge implicitly. As he has remarked on the campaign trail, his very right to be married came down to the vote of one Supreme Court justice. In defense of the 5-5-5 plan, he told Vox, “We need to make serious reforms to the Supreme Court to restore American’s trust in the institution and make it less political.”

The 5-5-5 theory is wonderful, but it might not survive contact with reality. The first challenge is that the idea of a moderate judge is largely a myth. A judge who is seemingly moderate in one area of the law might be a whacked-out extremophile in some other area.

Consider former justice Kennedy. On the campaign trail, Buttigieg has held him up as an example of someone who would fit the definition of a moderate under the 5-5-5 plan. Kennedy gets this mantle because he sometimes broke with Republican orthodoxy, at least in the areas of LGBTQ equality and abortion rights.

But Kennedy, a Ronald Reagan appointee, was also a First Amendment absolutist whose extreme positions led him to write the Citizens United decision, which more or less destroyed campaign finance reform in this country. He might not have been the most fire-breathing conservative justice, but he was certainly a justice who sided time and again with cases that supported the Republican or Trumpian agenda. It was Kennedy who provided conservatives with the fifth vote they needed to ruin gun regulations in District of Columbia v. Heller, and he was the fifth vote in Trump v. Hawaii, the case addressing Trump’s Muslim ban.

The legacy of a justice like Kennedy highlights the challenge of finding moderates at any level of the judiciary. But there’s a second, perhaps more serious problem with the plan. The Constitution quite clearly gives the president the power to appoint justices; it says nothing about the members of the Supreme Court getting to choose their own colleagues.

Here is the appointments clause as it appears in Article II of the Constitution:

[The president] shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law: but the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.

That seems fairly straightforward. It says the president “shall nominate” and the Senate can “consent” to the appointments of ambassadors, public ministers, and “judges of the Supreme Court.” Epps and Sitaraman try to get around this by arguing that the visiting justices would be “inferior officers,” and thus their appointments could be delegated by Congress to the Supreme Court.

Perhaps. But here’s the thing to remember when debating the constitutionality of any court reform plan: It’s the current Supreme Court, stacked as it is with conservative appointments, that will make the final decision as to whether a plan is constitutional. Who wants to be the one to tell Roberts that his power should be greatly reduced because his institution is full of partisan hacks and is broken beyond repair?

Buttigieg says that 5-5-5 is just one idea he’s floating and that he’s open to other solutions. This particular reform plan is what a fair-minded Supreme Court would reasonably look like. But we might need better justices, working with politicians who are better humans, operating under a better Constitution, to actually get there.

Forever Is a Long Time

A central goal of 5-5-5 and similar reform plans is to address the partisanship and politicization of the Supreme Court. But there are other proposals that accept the fundamentally political nature of the court and simply try to manage the issue in a fairer, less rancorous way. Term limits would be one way to achieve this, largely by making sure that the randomness of death (and the luck of the party that happens to be in power at the time) does not have generational consequences on our rights and freedoms.

The problem with term limits is our antiquated Constitution. Article III is pretty clear that Supreme Court justices hold their appointments for life: “The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour.” You can tell this line was written at a time when nobody got flu shots and people could die from pissing off Aaron Burr.

Yet there is a solution to the constitutional mandate of lifetime appointments, and it has already been implemented in every “inferior Court” in the country. Lower federal courts are still subject to Article III, but they offer judges the opportunity to take “senior status.”

Senior status is established by statute and has been deemed perfectly constitutional. It’s a semiretirement option offered to judges who reach 65 years of age and have achieved the Rule of 80—that is, their age plus their number of years in service on the federal bench equals 80. Senior judges still take cases, at their discretion or the discretion of the chief judge of their circuit. They still draw a full salary. In fact, over 30 percent of federal Circuit Court judges (just one step below the Supreme Court) have senior status, and those judges handle about 15 percent of circuit cases. But they don’t formally take up seats, which means that a president can nominate others to replace them. When the full circuit sits to review a case, only active judges typically participate.

The Supreme Court doesn’t do this, but it could. Fix the Court, a group dedicated to reforming the Supreme Court, has perhaps the clearest term-limit proposal. New justices would be limited to a single 18-year term. Those terms would be staggered so that no one president would get to name a disproportionate number of justices. When their terms are over, the justices would take senior status at full salary, avoiding the problem of lifetime tenure.

The idea of staggering justices across presidential terms is key. The obvious partisanship around Supreme Court retirements is one of the worst features of our current system. Kennedy, for instance, retired specifically so that a Republican president could appoint his replacement. He’s healthy, and if Hillary Clinton had won the Electoral College in 2016, he’d likely still be on the bench. Yet we find ourselves in a situation where 86-year-old Ruth Bader Ginsburg has to live until at least January 20, 2021, or women’s rights will be lost. Staggered term limits would ensure that electoral winners shaped the Supreme Court, not the Grim Reaper.

In recent years, the logic of this approach has become more popular. Polls have shown that a majority of Democrats and Republicans support term limits for justices. Fix the Court’s plan was recently endorsed in an open letter signed by 63 legal scholars from across the ideological spectrum. Conservative columnist John Fund has written positively about the proposal in National Review, of all places. Former presidential candidate Andrew Yang is on record as supporting the plan. Bernie Sanders has expressed interest in some version of term limits. Even one current Supreme Court justice, Stephen Breyer, has applauded the idea. “I think it would be fine to have long terms, say 18 years or something like that, for a Supreme Court justice,” he said. “It would make life easier. You know, I wouldn’t have to worry about when I’m going to retire or not.”

But there’s a catch. Just because senior status has been deemed a constitutional option for the lower courts doesn’t mean the same can hold true for the Supreme Court. As Harvard Law professor Laurence Tribe, a proponent of term limits in theory, explained the difficulties to me, “For several years, I was inclined to favor term limits, but I’m increasingly doubtful that the Supreme Court, as currently composed, would agree that Article III can be interpreted the way it would have to be in order to make Supreme Court appointments terminable after a fixed number of years…. That, in turn, suggests that the massive effort and political capital that would be required to get a federal statute enacted limiting the terms of Supreme Court justices just wouldn’t be worth it.”

This is the most difficult barrier for many court reform proposals: the current Supreme Court. While Congress can add justices without the need for constitutional review, the most innovative and nonpartisan reforms require the partisan Supreme Court to agree.

For Tribe, this leads us back to where we more or less started. “That leaves only old-fashioned court packing, which I’m open to discussing but have serious political—though not constitutional—doubts about,” he said.

Supreme Circuit

The most inelegant and politically charged version of court reform is, ironically, the version least likely to be quashed by the Republicans on the Supreme Court. We know that raw, unadulterated court packing is constitutional because changing the number of justices has been done multiple times in our history. With enough political power in the Senate and the White House, Democrats could add two, four, even 100 justices and simply dare Republicans to pull off the same feat the next time they’re in control.

This kind of tit-for-tat might be a satisfying response to McConnell’s manipulation of the court. And it solves, or at least salves, the problem of Gorsuch’s illegitimacy and Kavanaugh’s alleged immorality. But adding, say, two justices is not really a reform. It’s revenge.

There is, however, a way to reimagine court packing as a form of judicial reform instead of partisan reprisal. The reform involves making the Supreme Court operate like the Circuit Courts of Appeal. These courts are partisan, to be sure, but they’re not facing the same legitimacy crisis that we’re seeing on the Supreme Court. That’s because, in addition to the fact that many have more members, they have two things the Supreme Court doesn’t have: panels and ethics.

Once they’re appealed to the circuit court, most cases are initially heard by a three-judge panel. These panels are chosen at random from the members of that circuit. The panel renders a decision, and most of the time, that ruling is final. It takes a vote by a majority of the circuit to agree to have the case heard en banc (that is, in front of a full court). Only a vanishingly small percentage of cases ever make it there. The Second Circuit, for instance, hears less than 1 percent of its cases en banc.

Panels are great for the appearance of legitimacy. The random wheel makes it impossible to predict which judges will get which case and thus the way that a case will go. The court can still overrule a panel en banc, but again, it takes a majority to do so. That’s a significant contrast with the way the current Supreme Court operates. It takes only four votes—a minority—for the court to grant certiorari and agree to hear a case as a full body.

Panels don’t remove partisanship from the lower courts. There’s a reason Democratic state attorneys general rush to the Ninth Circuit and the Republicans rush to the Fifth. But that’s why adding justices is a critical part of reform. Packing the court could mean more diversity—more ethnic diversity, more gender diversity, more diversity of thought and experience. That diversity itself would be a moderating influence on the court.

While I said earlier in this piece that moderate justices don’t really exist, moderate opinions are written all the time. They come into being when judges write opinions as narrowly as possible in order to attract a majority of their colleagues to sign on to them. The Ninth Circuit operates with 29 active judges, the Fifth Circuit with up to 17. In the case of en banc hearings, it’s almost impossible to imagine a string of 15-14 or 9-8 cases on those circuits that would have the same sweeping impact as the torrent of 5-4 opinions we can expect from the Supreme Court this June.

Moving the Supreme Court to a panel system is an idea that reformers, scholars, and even some judges have suggested. But to finish the job of making the Supreme Court act like a real court and less like the enforcement arm for whichever party holds a majority, we need to add one final condition: ethics reform.

The Supreme Court is the only court in the land whose judges operate under no ethical guidelines. The Constitution says the justices hold their positions while in “good Behaviour,” yet nobody has defined precisely what that entails for these nine people. I’d argue that sexual harassment is not good behavior. I’d argue that attempted rape and lying under oath are not good behavior. I’d also argue that holding a meeting and taking a picture with people who have active business before the court is textbook unethical and, as on any other court, should require justices to recuse themselves from that active matter.

Yet we live in a world in which Kavanaugh and Justice Samuel Alito can and do meet with a member of the National Organization for Marriage, an anti-LGBTQ group that has filed an amicus brief in a case that the court is considering on whether gay and transgender workers are protected under the Civil Rights Act. We live in a world in which Justice Clarence Thomas regularly hocks himself out to partisan Federalist Society events. Nobody can stop them from doing this, because the ethical rules that govern a random traffic court judge in Peoria do not apply to the Supreme Court justices.

Simply subjecting the justices to the same ethical rules that govern all other lifetime-appointed federal judges would be a sea change in terms of how the court operates. The partisan bias that is now so open that it threatens public faith in the court would at least have to be tamped down. Even more important, ethics reform would open the door to the kind of accountability that’s been needed since long before the Me Too era. A lifetime appointment cannot be a license for past or present sexual harassment.

Roberts has long resisted ethics reform (though he has recently been alleged to be studying the issue). That’s how I arrive at my preferred number for court packing: 10 additional justices, to overrule the nine others who may consider themselves beyond ethical accountability. A 19-member Supreme Court, hearing most cases in panels and subject to ethical standards, would look, feel, and act more like every other federal court. It would still be a partisan institution, and it could still be manipulated via deaths and retirements, but uplifting the Supreme Court to the standards in place for the lower courts would still count as meaningful reform.

There’s one final advantage to coupling court packing with ethics reform. If the Democrats win the White House and take back the Senate, adding 10 justices would give them the political leverage to make the Republicans an offer they couldn’t refuse: If they agreed to bipartisan support of a judicial reform package, then the 10 new justices could be evenly split between Democratic and Republican nominees—allowing Republicans to maintain their current, ill-gotten, one-vote majority. Reducing Kavanaugh to one of 19 and subjecting him to ethical strictures are bigger long-term goals than expanding the court to 11 and hoping Republicans never win the presidency again.

History has shown us that purely partisan court packing doesn’t work or is easily overcome by the next administration. Nonetheless, court packing might be the only tool for court reform the Constitution currently allows. Most reformers want a scalpel, but the Constitution has perhaps provided only a hammer. Still, in the right hands, a hammer can be used to build something.

Supreme Court reform remains a nascent preoccupation, limited largely to wonks and advocates, but some kind of reform must happen under the next Democratic administration, whenever that is. Republicans have changed the rules when it comes to Supreme Court appointments. We can’t just go back to the way things were before Kavanaugh, before Gorsuch, and before McConnell.

The Republicans didn’t win the Supreme Court in one day or in one election. They spent a generation figuring out how to take control of it. They poured money and political resources into promoting their vision, and they built an entire infrastructure to help them pull off a full-scale heist of the Supreme Court in broad daylight.

Democrats must battle back. These court reform proposals are the first wave. They’re good. They’re nonpartisan. If Democrats can’t win cases at the Supreme Court, winning anywhere else won’t really matter.