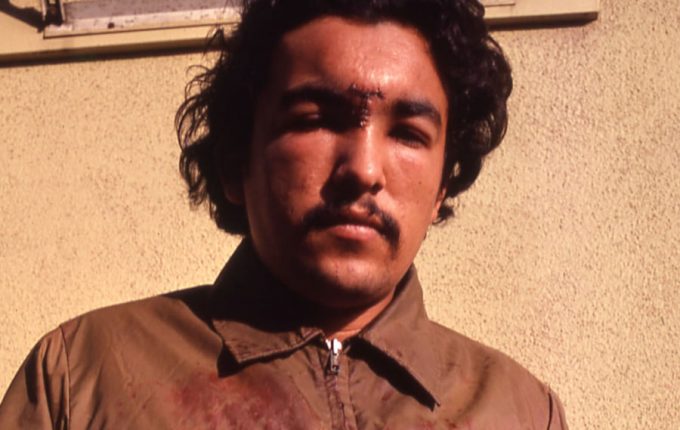

On the night of March 23, 1979, Roberto Cintli Rodriguez lost his ability to dream. Rodriguez, a journalist, was in East Los Angeles reporting for an article in Lowrider magazine about police violence when four baton-wielding LA County sheriffs beat the living dreams out of him.

As he recalls the incident, I remember reading about the 538 mostly young, brown kids arrested that weekend. Their crime? Cruising on Whittier Boulevard—the de facto center of the lowriding world. I have my own stories of official violence going back to the police beatings of local Latino cruisers under San Francisco Mayor Dianne Feinstein in the 1980s. I identified with Rodriguez’s story—a story the city’s main news outlet, the Los Angeles Times, ignored. But I had no idea about the astonishing effects the assault would have on him decades later.

“For years, I literally couldn’t remember my dreams or my nightmares,” he tells me during our conversation last week. “Those parts of me were erased.”

Last May, Roberto, an associate professor emeritus in the Mexican American Studies Department at the University of Arizona, released the latest iteration of one of his most important dreams: the Raza Database Project (RDP), a project aiming to document the nightmarish, violent effects of Latinx erasure. He and a team of volunteer researchers, journalists, and family members of Latinos killed by police produced a definitive report documenting an undercount of over 2,600 Latinos who have died at the hands of local police officers since 2014, a number that’s twice as large as what was previously reported.

There, in the cold anonymity of the statistics, he saw the mark of his old foe: erasure.

“One day,” he says, “I was looking at the ‘Unknowns’—people not identified in any racial or ethnic category—and saw all these names I recognized: Lopez, Martinez, Gonzalez, Ramirez. I asked myself, ‘Why are these people in this category?’ Because the federal government doesn’t keep a comprehensive, standardized count of who’s killed.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

His project and story bring to mind the forgotten names and images encountered during recent drives to numerous California cities and towns: Sean Monterrosa, an unarmed man shot and killed in Vallejo on June 2, 2020; James De La Rosa, a 22-year-old oil field worker shot dead by police officers in Bakersfield (where police officers have killed more people per capita than anywhere else in the United States); Andrés Guardado, an 18-year-old Salvadoran man shot in the back and killed by the same Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department that beat Roberto. While locals know their names, these and thousands of others remain faceless and story-less in the annals of US police violence.

“California,” Roberto adds “is literally a killing field everywhere, but nobody outside our community knows it.”

Roberto’s journey into the heart of darkness of police killings points to an even larger issue: how the systematic deletion of Latinx people by government databases, the media, philanthropy, Hollywood, and other institutions enables not just police violence but a whole host of other ills. From devastating immigration policies and employment discrimination, to reduced government funding and the colonization of Puerto Rico, these and other afflictions all have an element of removing Latinx people from their own stories.

This institutional erasure refers to the ways institutions and society at large suppress or completely silence a group in archives and narratives, as well as in discourse that subtly dehumanizes and sets up Latinx peoples for various forms of oppression.

Roberto’s talk of California as a “killing field” is familiar to me. I recall the silences that preceded the mass murder of hundreds of thousands of Central American peasants ignored before and during and after the war of the 1980s.

Since then, I have watched and documented how the nefarious workings of the removal of Salvadorans and other Central Americans from our own stories have extended across 2,500 miles of migration, mass graves, gang and narco violence and other symptoms of unstoried and devalued life. In 2018, I wrote for the Columbia Journalism Review about how most of the national coverage—on-the-ground reports, think pieces, features, op-eds—about the child refugee “crisis” in print and electronic media made it seem as though the crisis was “new,” as if the mass caging and separation of thousands of child refugees didn’t begin in 2014, during the Obama years.

Two researchers and I also found that the only representations of the Hondurans, Guatemalans, and Salvadorans who are at the center of this story were two-dimensional images of pain and soundbites of suffering. No Central American scholars, lawyers, nonprofit leaders, or journalists were included in any of the stories from any of the major media. Not one. And the pattern continues, as documented in a recent study by the media watchdog Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting.

The effects of this selective official silence are hardly lost on Central Americans like Ana Luna, a Salvadoran refugee who fled gang violence only to be imprisoned with her son in the Karnes Family Detention facility by the Obama administration in 2014. When I asked her about the massive news coverage of Trump’s “border crisis” in 2018, she responded, “Only those imprisoned by Trump matter. It’s like the thousands of us jailed by Obama never existed.” Many fear that a similar erasure awaits the Central American refugee children and mothers being imprisoned by Biden.

Columbia University scholar Frances Negrón-Muntaner listens to these stories of physical and cultural violence against Latinx peoples and hears the workings of official amnesia.

“Power always has archives,” she says. “Police, the state, hospitals, schools, Hollywood, the news media. Any institution that exercises power generates an archive of its founding, its operations. One of the ways Latinos are erased is that the data and stories generated by these institutions are not collected into their archives. The other form of erasure is that the materials may be there but the narratives are not there and are not incorporated into the larger narratives of the country. Latinos have both, and this creates all kinds of profoundly disturbing problems.”

In 2015, Negrón-Muntaner and a team of researchers found that while the Latinx population makes up almost 60 million people—over 17 percent of the United States—they represented only between 2 and 8 percent of the leading actors, directors, showrunners and all other key positions in the television and movie industry. A recent LA Times series on Latinx inclusion in Hollywood found that the situation has actually gotten worse since Muntaner’s study. Statistics on employment in the news media show a similar trend: Latinos as the least represented group in the US news industry proportional to their population. (Disclosure: Her report includes a 2009 campaign I led to remove Lou Dobbs from CNN.) It’s a fact that Muntaner sees as demanding activism. “Ending this means confronting white supremacy.”

Though grounded in white supremacy, the practice of erasure is not just a white phenomenon, a fact Roberto knows well.

“As I started sharing the research,” Roberto Rodriguez tells me, “some Latinos actually asked me, “Why you doing that? That’s not our issue. Our issue is immigration, not violence.”

He and Muntaner see these responses as forms of colonialism reinforced by the selective memory of physical, psychic, and other violence. Lacking any memory of the history of killing and catastrophe that has shaped different Latinx identities in, say, the colonization of Puerto Rico or the pillaging and state terrorism (see the lynchings and murder of thousands at the hand by Texas Rangers during the Matanza in the Lone Star State) of the parts of the United States that used to be Mexico, different Latinx groups lack any serious explanations for either the current violence or the discrimination and racism we experience. A very recent example of this is the deletion of Afro-Dominicans from Lin Manuel Miranda’s In the Heights, despite the fact that they are the great majority of Latinx people living in Washington Heights.

Roberto wakes up every morning to the sight of the big T-shaped scar between his eyes left by the Sheriff’s beating, but remains undaunted in the pursuit of his dream of ending erasure, as if the “T” stood for “Truth.”

“For a time, they made me lose my ability to dream,” he says. “But I never lost the ability to remember.”