As I walked along Manhattan’s 11th Avenue one day in late April, the wind seemed as if it were trying to blow the plywood outdoor-dining huts over and rip the spindly trees from the ground. I arrived early to the Gotham West Market food court. My date, Andrew Yang, showed up unfazed by the violent weather, as buoyant as he appears on TV.

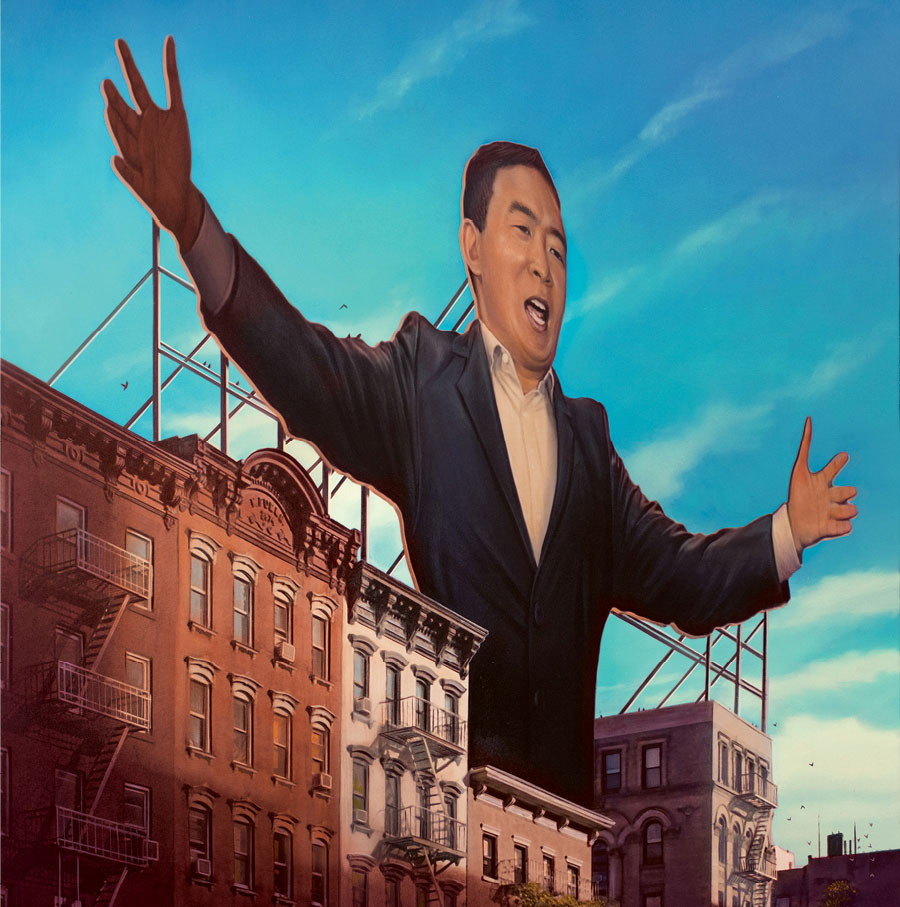

A candidate for mayor of New York City, Yang is a businessman and failed nonprofiteer with no experience governing and a hodgepodge of centrist, liberal, banal, and just plain quirky opinions. He has some potentially interesting ideas—a public bank, for instance—but he also loves solutions involving philanthropy and public-private partnerships. And right now, although Eric Adams, an ex-cop and a more conventional politician, has been pulling ahead recently, Yang is polling well with every demographic, including those identifying as progressive or liberal. With his name recognition, he could easily win a race made less predictable by the city’s new ranked-choice voting system. The former executive of a small test-prep company, Yang may well become the next mayor of the biggest city in the United States. I wanted to know how a Mayor Yang would address the concerns of the progressive movement, from racial injustice to affordable housing to the climate crisis.

Given the inhospitable weather, we decided to eat indoors (a pandemic first for me). Yang, wearing his usual dark blue blazer over a dress shirt with no tie, exuberantly assured me that the pizza here—from Corner Slice, an upscale enterprise aesthetically evocative of a vernacular New York pizza shop—is “the best.” I decided to have what he’s having, the “special,” festooned with a suspicious variety of items. Pizza is a risk for any New York City mayoral candidate—when Bill de Blasio ate a slice, inexplicably, with a knife and fork, it was a tabloid scandal—but particularly for Yang, who has drawn mockery for his lack of authenticity as a New Yorker. His social media posts have reflected confusion on points ranging from the meaning of “bodega” to the trajectory of the A train, and he’s been roasted for being a “bandwagon fan” of the New York Knicks. In this light, it seemed bold of him to consume a pricey square slice of pizza with a journalist, but Yang is too confident to worry about such things.

The candidate, who’s 46, grew up in Westchester County north of the city. Raised by immigrant parents from Taiwan, he remembers almost no political discussion in his house. Once, he recalled, his mother looked at the TV and said, “I don’t like him.” Yang is pretty sure “him” referred to “one of the George Bushes.”

Eating pizza with Yang made clear to me why he is popular with New Yorkers. He does not bring up his competitors’ scandals in conversation. He often changes the subject when asked about big, systemic issues, but he knows what most New Yorkers, especially the apolitical, care about: bringing back jobs, returning kids to school, lowering the murder rate, and getting some cash relief.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

He told me he donated to Bernie Sanders’s presidential campaign in 2016. He also said he voted for Cynthia Nixon, the Sex and the City actress turned education activist who challenged Andrew Cuomo for governor in 2018. Still, his politics are largely those of a centrist or conservative Democrat, friendly to school privatization schemes and cops. He did not join any of last summer’s protests over George Floyd’s unconscionable murder by a police officer, though he has met with family members of people killed by police violence and did attend a vigil for the victims at a church, an event he went out of his way to describe as “very peaceful.”

I asked Yang about education. After three decades of struggle and lawsuits by public school parents and community activists, the state legislature decided this year to fully and equitably fund New York City’s public schools. Parent advocates won the court battles years ago: The state was found guilty of underfunding city schools and had been under a court order to allocate billions of dollars to the city’s public schools to enable them to provide “a sound basic education” to their students, most of whom are Black or brown. But it took much more organizing and protesting, and the election of a progressive legislature, to finally put that funding in the state budget this year. The city will also be flush with new federal reopening funds. This seems like an exciting opportunity to address the persistent racial and economic segregation and inequality that has plagued the system. What’s Yang’s plan? He listened politely but a little blankly, as if much of this information was new to him.

“I mean,” he said doubtfully, “I would love to make progress on some of these inequities.” But, he insisted, the most urgent issue is reopening the schools. The topic has become a signature one for Yang, and it shows how attuned he is to the moment: Many parents are, indeed, desperate to have their kids back in school full-time. Not having school, sports, and normal sociability has been devastating for some children’s mental health and for most kids’ development, he emphasized. I’m a public school parent, and it feels good to have our suffering acknowledged by a prominent person.

I pointed out, however, that he wouldn’t be taking office until January 2022. Mayor de Blasio has said that all students can go back to school full-time in the fall. Some elementary school students are already attending full-time, and city officials say more may have the opportunity to do so later this spring. High school sports are back. Teachers have had the chance to be vaccinated by now. Many adults in the surrounding community have, too (at this writing, more than half of Manhattan, more than a third of Brooklyn and Staten Island, and more than 40 percent of Queens has been fully vaccinated). Won’t this be a settled issue by the time Yang takes office? “You’d hope!” he said skeptically, “but I’m really concerned.”

Yang has crusaded against other pandemic measures that are likely to be irrelevant to his mayoralty, calling for fully reopening the bars. A few days before we met, he held a press conference denouncing the Covid rule mandating that food be served with drinks. That’s a matter of policy decided by the state, not the city—and the legislature repealed it the next day.

Aweird thing about Andrew Yang is that everything he says sounds reasonable unless you know anything about the topic. He talks a lot about making New York a hub for cryptocurrency, but as James Ledbetter of FIN, a financial technology newsletter, pointed out, the state’s intense regulatory environment, in which engaging in any virtual currency business activity is illegal without a license, makes that idea ridiculous. “Much depends, I suppose, on the definition of ‘hub,’” Ledbetter told me. “But New York’s reputation among blockchain and cryptocurrency companies is as a place to avoid, and changing that reputation would appear to be largely outside the capabilities of the mayor.” Over lunch I asked Yang about this, and a mush of buzzwords about blockchains and “trust” ensued.

He’s famous for giving more prominence to the idea of a universal basic income, which is intriguing, but his proposal is neither universal nor basic (just $2,000 a year for some of the poorest New Yorkers). Yang, courting the city’s Orthodox Jewish community, has praised the academic quality of the Orthodox yeshivas, but years of research, lawsuits, and testimony by graduates show that many of them don’t meet their obligations to provide even a basic education. He’s floated the idea of a city takeover of its transit system, which seems sensible—if you don’t know that the funding is controlled by the state, a knowledge gap that met with consternation from experts interviewed by Politico.

Yang doesn’t know what he’s talking about. He hasn’t followed the long-term social and economic issues that have consumed the city’s most political people for years. But he does know something that the city’s institutional left seemingly doesn’t: what people who don’t care about politics care about. Getting kids back in school. Having fun again. Being safe on the subway and in the streets. Helping businesses that have suffered. Looking forward to the future.

As the New York City political journalist Ross Barkan has written, “Laugh at him at your own peril.” Yang sounds silly to the knowledgeable, but the idea of a return to better times is a powerful one. His vibe and rhetoric remind me of Ronald Reagan’s “Morning in America,” one of the most successful political appeals in US history. And didn’t the liberal media also laugh at a certain repellent weirdo’s promise to “Make America Great Again”?

Yang benefits from being much more plugged into the zeitgeist than progressives are. The left lacks a clear message on school reopening. Several left-wing education groups even counterprotested Yang’s reopening rally on May 1. You could disagree with the feasibility of the rally’s demand—fully reopen now!—but to counterprotest means what? Don’t reopen school, even as the pandemic wanes and the federal money pours in?

Yang speaks to another visceral issue on most apolitical people’s minds and overlooked by New York’s NGO left: high murder rates. In a time of constant news alerts about shootings and stabbings in the city—New Yorkers may remember the terrifying “A train slasher” this winter—calls to defund the police (though correct), coming from people largely silent about such violence, can seem tone-deaf. In fact, given how often high crime leads to far-right political reaction—please note that Brooklyn and Staten Island Republicans have endorsed Guardian Angels founder and racist madman Curtis Sliwa for mayor—we may be getting off easy with Yang, who speaks in measured tones about stopping both crime and police violence.

So far, no left mayoral candidate is as good at running for office as Yang is. In last year’s state Senate and Assembly races, New York’s left—including but not limited to NYC-DSA—ran charismatic, visionary candidates who addressed broadly popular priorities like taxing the rich, single-payer health care, renters’ rights, affordable housing, stopping police violence, and funding public schools. They won big. In contrast, the progressive candidates for mayor—Maya Wiley, Dianne Morales, and Scott Stringer—have been unremarkable.

Yang is also not vulnerable on the things that trigger the most outrage on the well-informed left, since that is not his base. When Yang was caught awkwardly shrugging off a sexist joke, Wiley took him to task in an Internet ad. Her scolding manner and stern visage offered a bracing reminder of why some voters preferred Trump to Hillary Clinton. Stringer has hemorrhaged endorsements because of a sexual harassment accusation, while Yang has been unharmed by complaints of sex discrimination and anti-Blackness by a few former employees. None of these charges have been proven, but among Stringer’s base of nonprofiteers and political activists, he’s toast even without any evidence, while Yang’s “base”—that is, most people—probably aren’t paying much attention.

Yang sometimes floats ideas that are absurd and terrible—a casino on Governors Island, a crackdown on street vendors—and then backs off from them amiably. He issued an appalling statement in support of Israel, then walked it back after criticism from Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and his own staff. Despite his “bro” reputation, he doesn’t exude toxic masculinity; he can change course when he’s wrong. To follow his campaign statements, then, is to constantly oscillate between alarm and relief.

The week before our lunch, on Earth Day, I met Yang for the first time. I went out to see him give a press conference in the Rockaways, a coastal area of Queens that was devastated by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. It was a cold day, and the area felt gray and deserted. From the A train I saw buffleheads, cormorants, and a couple of egrets. Rockaway Community Park, the site of the press conference, is at the base of what used to be the Edgemere Landfill. The area is owned by the city, but only a small portion of it is clean enough to use as a public park. Yang is here in support of a proposal to install solar panels on the still-toxic part of this property. When I got there, I met Tina Carr, the policy director of AC Power, a group that promotes and develops solar energy projects on landfills and brownfields. She called the idea a “no-brainer” and was thrilled to have Yang’s backing.

Yang, sporting the cheery orange and blue striped scarf he always seems to wear in cold weather, praised the project quickly but sincerely, then expounded a bit on getting rid of burdensome red tape. He meant this to be in support of helping the environment, but this kind of language is, of course, beloved by polluters and libertarians.

A TV reporter asked about a letter signed by hundreds of prominent Asian and Pacific Islander American progressives declining to support Yang because he is not progressive enough. Yang was on surer ground here. He’s clearly aware that his base is the apolitical: “I take exception to, frankly, trying to categorize people in various ideological buckets. Most New Yorkers are not wired that way.”

A journalist who lives in the Rockaways asked about ferry service to the area. Yang has criticized the New York ferry service, since it is heavily subsidized by the city and its ridership is low. “It’s heavily subsidized, but we need it,” the man said. “This is a transit desert.”

Yang wasn’t sure about that one. He said he’d look into it.

If you’ve ever knocked on doors or made phone calls for a political campaign, you’ve probably encountered that guy who doesn’t know the issues but won’t commit to your cause because, he says, he has to do his own research. “Andrew Yang is that guy,” said Susan Kang, a political science professor at John Jay College and a cofounder of NO IDC NY, which successfully ousted a group of conservative Democrats from the state legislature in 2018. (Kang is also one of the signatories to the anti-Yang letter.) If you’ve encountered that guy, you may have suspected that he isn’t, in fact, planning to do any research.

Who wouldn’t love the idea of turning toxic municipal properties into solar farms? But the rest of Yang’s climate plans are vague compared with the lengthy specifics that some of his mayoral competitors, especially Stringer and Kathryn Garcia, have provided. And when I interviewed Veekas Ashoka of the Sunrise Movement NYC, along with some of his colleagues, Ashoka asked why Yang’s climate plan accepts the Biden administration’s climate targets: As one of the richest and most progressive cities on earth, shouldn’t we aspire to do better than the federal government, to be leaders on this issue? Another youth climate activist I interviewed separately made the same criticism.

When I raised the climate activists’ exhortation with Yang over our pizza lunch, as angry winds continued to batter Gotham West Market, he beamed disarmingly. “I love that point!” he exulted. “I would love to drive past those goals.”

I asked if he’d ever researched the matter of the Rockaways’ ferry service. He admitted he hadn’t.

Yang’s press secretary told him it was time to go. As we stood up, a man in a Columbia Sportswear fleece waved him down, shouting, “Mr. Yang, we’re behind you!” He got a selfie with the candidate. The Yang fan was Jay Underwood, a principal at George Jackson Academy, a private school for gifted, mostly low-income boys. I asked Underwood why he’s so excited about Yang. He praised the candidate’s “connectivity” and reflected on what a role model Yang would be for his students, many of whom are Asian American. Underwood acknowledged sheepishly, “I don’t know much about policy issues.”