In 1905, the dancers of the Imperial Ballet in St. Petersburg went on strike. Their demands: higher wages, a five-day workweek, training in how to apply theatrical makeup, the right to wear their own pointe shoes. They elected a small delegation, which included star pupils Anna Pavlova and Vaslav Nijinsky, to represent them in negotiations. This modest political action at the Mariinsky Theater proved that the spirit of the Revolution of 1905 had seeped into nearly every crevice of Russian society. That year, a crushing defeat in the Russo-Japanese War left Czar Nicholas II vulnerable to the calls for change—calls that were now growing louder and more militant across the country. Russia had become awash in peasant uprisings, labor strikes, and military defections. These revolutionary impulses would soon be quelled—at least temporarily—by liberal reforms, but not before the dancers had staged their own revolt. The strikers were met with retaliation: Some were expelled from the company, others passed over for plum roles. Suddenly the possibility of taking their work abroad, in a nascent ballet company run by an art critic who seemed more preoccupied with set design than pirouettes, did not sound half bad.

This upstart company would sap the Imperial Ballet of its best people. In 1909 in Paris, Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes had its first season. Drawing from the luminaries of Russian modernism, the impresario amassed an unprecedented—and perhaps not since replicated—collection of talent, and not only from the world of dance. In addition to poaching Pavlova and Nijinsky, Diaghilev commissioned Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Rachmaninoff to compose new scores for his ballets. At a time when the set design for ballets revolved around paintings of castles or flowery landscapes, Diaghilev hired artists from the avant-garde to create his backdrops, calling on the Russian Cubo-Futurist Natalia Goncharova and—later—Pablo Picasso. The costumes designed by Leon Bakst were colorful and ornate, made from gauzy, transparent fabrics meant to evoke the Orient. Others were designed by Diaghilev’s good friend, Coco Chanel.

It would be almost impossible to exaggerate the influence that Diaghilev’s company had on modern ballet. The Ballets Russes pulled the medium of dance off its genteel pedestal; it replaced the grace and beauty of fairies and princesses with the religious frenzy and erotic desires of peasant women. At the dawn of a new century, it announced the arrival of the modern age. Virginia Woolf was a frequent attendee whenever it came to London. Ahead of its summer season there in 1912, Woolf invited a friend to come witness the city “all awhirl with Wagner, and Russian dancers.”

Diaghilev was the scion of a wealthy Russian family. As a young man, he took piano lessons with Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, who was part of a collective of nationalist composers known as “the Five,” which sought to create a distinctly Russian style of classical music infused with Slavic folk genres and that celebrated the country’s pre-Christian pagan roots. In 1907 Diaghilev brought the music of the Five to Paris in a special exhibition on Russian music, and the following year staged Mussorgsky’s opera Boris Godunov (replete with dancers in traditional folk costumes imported from the Arctic city of Arkhangelsk).The response was frenetic—all of Paris was enthralled by les russes, or at least Diaghilev’s Russians. Their image was purposefully primitive, that of the wild Slav whose artistic spirit could not be tamed by traditional Western forms or techniques. It was, Diaghilev realized, something he could sell—and sell well. When he applied the same ideas to ballet, after enticing many of Russia’s leading dancers to go abroad, the reaction was identical. As one critic described it: “The entire hall, carried away by the frenzy of the dances of the Oriental slaves and Polovtsian warriors at the end of Prince Igor, was ready to stand up and actually rush to arms.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

As the dance historian Lynn Garafola explained in her excellent 1989 book Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, in the absence of the state-funded imperial theater system, the company had to rely on the commercialization of national identity, which intensified its tendency for self-Orientalism and fed an unabashed willingness to serve as a kind of ethnic intermediary between East and West. While this was no great bother to Diaghilev, it hampered the careers of some of the company’s alumni. When Nijinsky left the Ballets Russes to do a residency at a theater in London, the owners were disappointed that his program did not include any Russian dances. The legendary dancer “did two or three movements from a Ukrainian squat dance,” writes Garafola, and yelled, “Is this what you want to see from Nijinsky?”

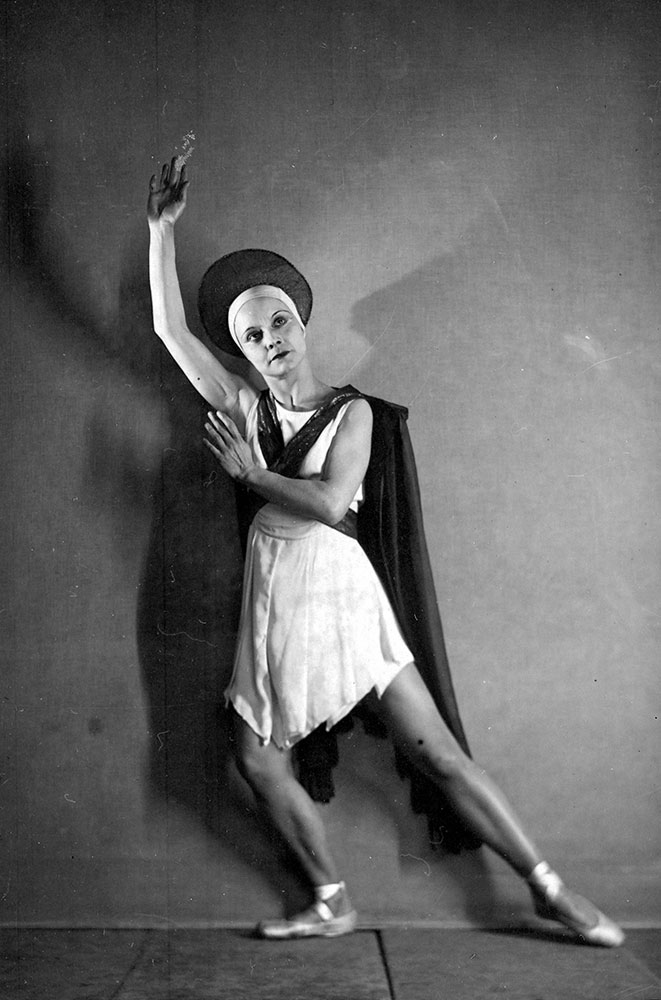

This last anecdote comes from Garafola’s new book La Nijinska, a biography of Nijinsky’s sister, Bronislava “Bronnie” Nijinska, told in rich, fascinating detail. Whereas her more famous brother suffered from schizophrenia, a condition that forced him to stop performing at age 30 and remain in Western Europe, Nijinska was able to travel back and forth between worlds. She returned to Russia in time to see the Bolsheviks seize power and quickly became enmeshed in the revolutionary art movements that were flourishing in a newly socialist Moscow and, later, Kyiv. She began to develop new theories of movement designed to open up dance to the masses. Later, when Nijinska returned to Diaghilev’s company in the 1920s, the market pressures on the Ballets Russes suddenly stood out for her in a way that they hadn’t previously—that is, before she’d seen a real alternative. Most important for Garafola, she also left a paper trail: a series of letters, diaries, and unfinished memoirs that have been stitched together here into an illuminating study—one that upsets the notion that the artists who fled the Soviet Union for the West found untrammeled creative independence. For Nijinska, the market felt anything but free.

Bronislava Nijinska was born in 1890, in Minsk, to Polish dancers who made a living performing in provincial theaters across the Russian Empire. The couple were constantly on the move in pursuit of work, as evidenced by the fact that each of their children was born in a different regional capital (Kyiv, Tblisi, and Minsk). Despite this itinerancy, “it was an enchanted childhood,” Garafola assures us. “As they moved from city to city,” the children “learned their letters in Polish and Russian, listened to balalaikas playing at sunset along the Volga, and began their training as dancers.” Their mother harbored bigger ambitions for them—namely that they would escape her fate and find secure (and prestigious) employment with the state. So she rejoiced when Vaslav and Bronnie were admitted to the Imperial Ballet School in St. Petersburg in 1898 and 1900, respectively. After completing the eight-year course, both were hired to perform in the corps de ballet for the Mariinsky, the leading ballet theater in the country and arguably the world. However, Vaslav, who made no secret of his sexuality, began pursuing the Paris-bound and deep-pocketed Diaghilev, as both a lover and a patron. “By the fall of that year,” Garafola writes, “the impresario had succumbed” and invited Nijinsky to join his Paris company for its opening season. At their mother’s urging, Vaslav grudgingly negotiated a spot for his sister; he used her to test out new choreography, punishing her body with the grueling task of rehearsing the danse sacrale, the scene in The Rite of Spring in which a pagan girl dances herself to death as a human sacrifice. In other words, normal sibling behavior.

Nijinsky was the principal dancer of the Ballets Russes, a role typically held by women. He was praised for dancing “like a girl”—that is, on pointe. Audiences and critics were enraptured by his physical beauty, lithe body, and superlatively high jumps. Others speculated that his allure rested in the racial ambiguity of his people, the Slavs, with one reviewer claiming that his features “suggested the Mongol rather the European.”

Though Nijinsky’s name is synonymous with the Ballets Russes, his tenure there was actually short-lived. Its first season as an independent, year-round company came in 1911, and Nijinsky was kicked out just two years later (when a jealous Diaghilev learned of his marriage to Romola de Pulszky, a Hungarian aristocrat from an illustrious family). Bronnie departed the Ballets Russes to join her brother’s new retinue, Saison Nijinsky, which was plagued by creative differences between Vaslav and his financial backers, not to mention Diaghilev’s attempts at sabotage (he forbade Bakst from collaborating with Nijinsky on costumes and tried to sue Nijinska for breach of contract). Nijinsky had a nervous breakdown and was taken to Vienna to convalesce.

Having witnessed her brother’s collapse from the stresses and expectations of commercial theater, in the spring of 1914, Nijinska returned to Russia. At first she danced in Petrograd (St. Petersburg’s less Germanic wartime name), in Narodny Dom, a government-run theater that offered opera and ballet at affordable prices. This was followed by a stint at the Kyiv City Theater. Eventually, in August of 1917, Nijinska made her way to a Moscow on the edge of revolution. She embraced the moment fullheartedly, becoming “a key figure of the choreographic avant-garde,” Garafola writes. Nijinska saw in socialism an antidote to the commercialism of Western Europe that had left her brother exploited and artistically compromised. She became convinced, Garafola notes, that the “intoxication with fame, celebrity, and the cult of the new was turning ballet into a marketplace” and dancers into “salesmen.” She dreamed of establishing a school of her own that would focus on the development of “spirit” rather than skill. “If the spirit is highly developed,” she explained in a treatise, “one won’t need the framework of socialism.” Spiritual awakening was not something that could translate into professional advancement, and such was the point. “Professionals should be destroyed” she declared.

Not long after the October Revolution, civil war broke out in Russia between the Red Army of the Bolsheviks and the Whites—an armed, ad hoc alliance of counterrevolutionaries. The fighting led to surging fuel prices and food shortages in Moscow, so by October 1918, Nijinska had fled to Kyiv. Amid the city’s relative calm, she was finally able to open her School for Movement. Her “curriculum,” Garafola writes, “differed significantly from other ballet schools. It offered no pointe, partnering, or variations classes, that is, classes designed to instill mastery of ballet technique.” In this political environment, technique was arguably elitist.

In Kyiv, Nijinska also found like-minded collaborators, working as a choreographer for Marko Tereshchenko, the leader of an experimental theater studio for proletarian youth called Centro Studio. Collective art forms were of central importance to the ascendant Soviet culture and ideology, and Centro Studio offered a perfect model. Open to everyone, regardless of skill level or experience, it was a manifestation of the idea, Garafola explains, “that socialist culture should be proletarian and collective.” Nijinska threw herself headfirst into the Soviet cultural apparatus, becoming a member of the Art Workers Union and helping to form the First Mobile Concert Troup “to introduce Red Army men to art in Kiev.”

No matter how committed they were to revolutionary ideals, however, artists like Nijinska found themselves being investigated by the secret police in the early 1920s. The Russian Civil War had bred a culture of paranoia, and Nijinska’s studio had come under surveillance for reasons that seem opaque even to Garafola. Whatever the reasons, the overall atmosphere in Kyiv grew increasingly intolerable. As the fighting moved closer to the city, the blasts became louder, so much so that Nijinska suffered a hearing loss that lasted for the rest of her life. Furthermore, her brother’s illness had become more serious, and she wanted to see him again.

In 1921, Nijinska paid to be smuggled out of Kyiv. Using old czarist rubles, she bribed her way across the Polish border and made her way to Vienna. Almost as soon as she arrived, she began to have regrets. She signed a lucrative contract with one dance hall, but it was only short-term. The following months were marked by poorly paid work and long hours. “She endured penury,” writes Garafola. Nijinska sank into depression, feeling that she had traded in the political pressures of art-making under the Soviets for the even more limiting ones that came with selling a commercial product. She became increasingly desperate to reconnect with the Ballets Russes, hoping it would give her a creative lifeline. As she wrote in her diary at the time, “Pregnancy with creativity is making me heavy and sick. I want to see Diaghilev; he is my ninth month; he could become the midwife of my creativity. He could become the father of my child.”

Still based in Paris, Diaghilev’s company had continued its run, but it now catered to White Russian émigrés who, like his own family, had lost their wealth and status in the revolution. Even so, Diaghilev invited Nijinska back into the company, asking her to help choreograph its new production of Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty, a politically reactionary choice for the time. With its depiction of “the splendor of French court culture under Louis XIV and his successor,” Garafola writes, the ballet was meant to satisfy a “conservative segment of the Russian émigré community.” Nonetheless, Nijinska took the job, believing that the creative spark that had first ignited the Ballets Russes could never be fully extinguished.

Three years later, when Diaghilev produced Le Train Bleu, based on a scenario by Jean Cocteau, Nijinska took on the role of lead choreographer. The ballet, Garafola writes, was about young, athletic, well-to-do Parisians who frolicked at “fashionable resorts” in “hand-knitted Chanel swimwear, bare legs, rubber bathing caps, and sandals.” One of the main characters was modeled on the popular tennis player Suzanne Lenglen. Yet while Nijinska had spent much of her career among wealthy aesthetes like Diaghilev, who catered to the tastes of the fashion-forward, she never considered herself part of that world. She approached the choreography for Le Train Bleu with a politically motivated stubbornness, consistently dismissing Cocteau’s suggestions to build in gestures and poses that connoted frivolity and excess; she had a “mulish determination,” Garafola writes, “to ignore the high life details knitted into Cocteau’s imagined ballet.”

Nijinska pushed forward, but she was horrified by the turn the Ballets Russes had taken. It was a “degradation of everything I expected to find here,” she wrote in her diary after working on Sleeping Beauty: “One should only do what one loves. One mustn’t sell one’s creativity. God give me strength. I want to go back to Russia so much.” Unlike the artists and other dancers around her, who had either remained abroad during the revolution or fled it straightaway, Nijinska had seen firsthand the flourishing of creativity and experimentation that was taking place in those early years of the Soviet Union. She knew what ecstatic art could be produced by committed thinkers keen to reject the staid traditions of the past and the hierarchies of the academy. However, as Garafola is careful to note, had Nijinska stayed in the Soviet Union through the 1930s, she would have encountered the repressive creative atmosphere ushered in by Stalin. Yet Garafola also outlines the many other obstacles Nijinska faced in capitalist Europe. “One can only wonder,” she writes, “how different her work might have been had she reopened her studio in Moscow of the 1920s, allowing her once again to choreograph in an environment free of commercial pressures.”

Wonder is all we can do. Nijinska spent much of the next decade in Europe, save for a brief stint in Buenos Aires, before eventually making her way to an environment certainly not known to be free of commercial pressures: Hollywood. She was there on the invitation of the theater director Max Reinhardt, who asked her to choreograph the dances for the 1935 film version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The big-budget production starred James Cagney, Olivia de Havilland, and Mickey Rooney. Sometime later, she opened Nijinska’s Hollywood Ballet School, where she trained actresses and aspiring ballet dancers, including Joseph Rickard, the founder of the First Negro Classic Ballet. Despite these accomplishments, Nijinska receded into the background relative to another ex-Soviet choreographer, who had become the darling of American dance: George Balanchine.

In 1917, Balanchine was in the middle of his training at the Imperial Ballet School when the Bolsheviks came to power and seized the institution, eventually renaming it the State Academic Theater for Ballet and Opera. In 1924, while on tour in Western Europe with the Soviet State Dancers, Balanchine and his wife decided to defect. He was hired by Diaghilev as a choreographer (succeeding Nijinska) and is often credited with remaking the company’s signature style into neoclassicism, a movement that transplanted 19th-century forms and techniques into pared-down, minimalist settings. In the 1930s, the staunchly anticommunist Balanchine came to New York City, working with wealthy patrons like Lincoln Kirstein, who together with the dancer opened the School of American Ballet. Balanchine’s career was also helped along by critics like Edwin Denby of the New York Herald Tribune, who believed that politics had no place in the world of ballet.

Balanchine, a dissident aesthete, made for the perfect Cold War cudgel. Nijinska, though she had her admirers, could never fulfill such a role. In 1944, she was invited to New York City by the Chilean-born ballet director George de Cuevas to choreograph the dances Brahms Variations and Pictures at an Exhibition. The music and narrative for Pictures, composed by Modest Mussorgsky, was “programmatic,” Garafola notes: “With ten episodes, each the remembrance of a painting…it imagined a spectator strolling through an art gallery and contemplating [the] works.” However, Nijinska completely abandoned the theme and choreographed scenes of Russian peasants at work in the fields, a kind of labor ballet. In his review, Denby mocked her “pseudo-Soviet ballet,” calling it “a stylization of Russian folk steps and village games with a good many chain gang huddles.” Nijinska hadn’t intended to stage anything like a protest or political commentary. What she had not fully appreciated, however, was that for an artist from the Soviet bloc, everything she did would be interpreted through that prism. Her crime, as far as her critics went, was not stripping the dance bare of popular spirit.

Nijinska returned to Los Angeles, where she lived until her death in 1972. Though there were frequent revivals of her work, including in New York, her theories of dance and movement never left the same kind of cultural imprint that Balanchine’s did. How could they? Balanchine had played the part of the anticommunist Soviet dissident to perfection. He publicly downplayed the importance of state funding for the arts: “America should always remain capitalistic,” he said, adding that “subsidies make you too relaxed, too serene.” His dancers, optimized to peak performance, were compared by Kirstein to IBM computers, “streamlined metal boxes.” He embodied the American ethos as only a defector from the Soviet Union could.

Though she had fled from the same place, Nijinska was escaping a political crisis, not abandoning her politics. As a choreographer, she would never fully acclimate to the strictures of the supposedly free world. Her spirit never left Kyiv, the city where she taught workers to move together as one.