The great jazz musicians didn’t write out elaborate scores in private like European classical composers did. Nor did they remain enclosed in their community like the virtuosos of African or Indian music. Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis—they all worked out their innovative sounds in public, onstage with others, under the bright lights of racism and capitalism. And while they all had to master a public performance tradition—including pleasing the toughest crowd of all, ballroom dancers—in the end they were each alone with their unique compositional perspective.

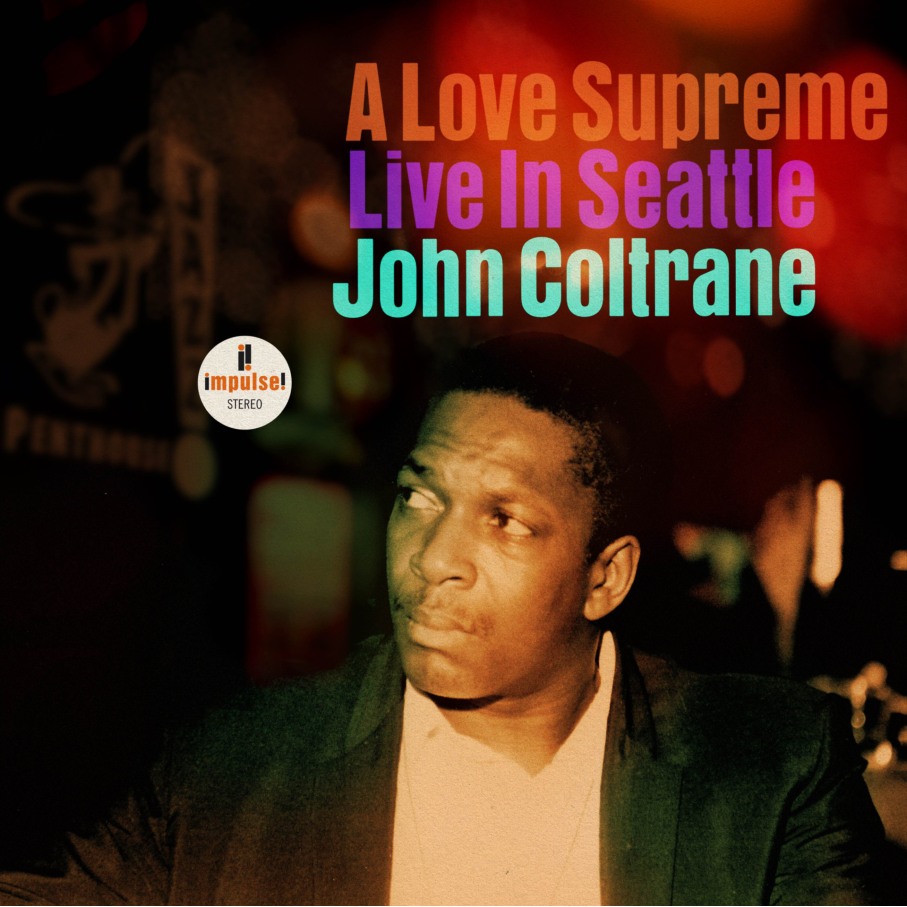

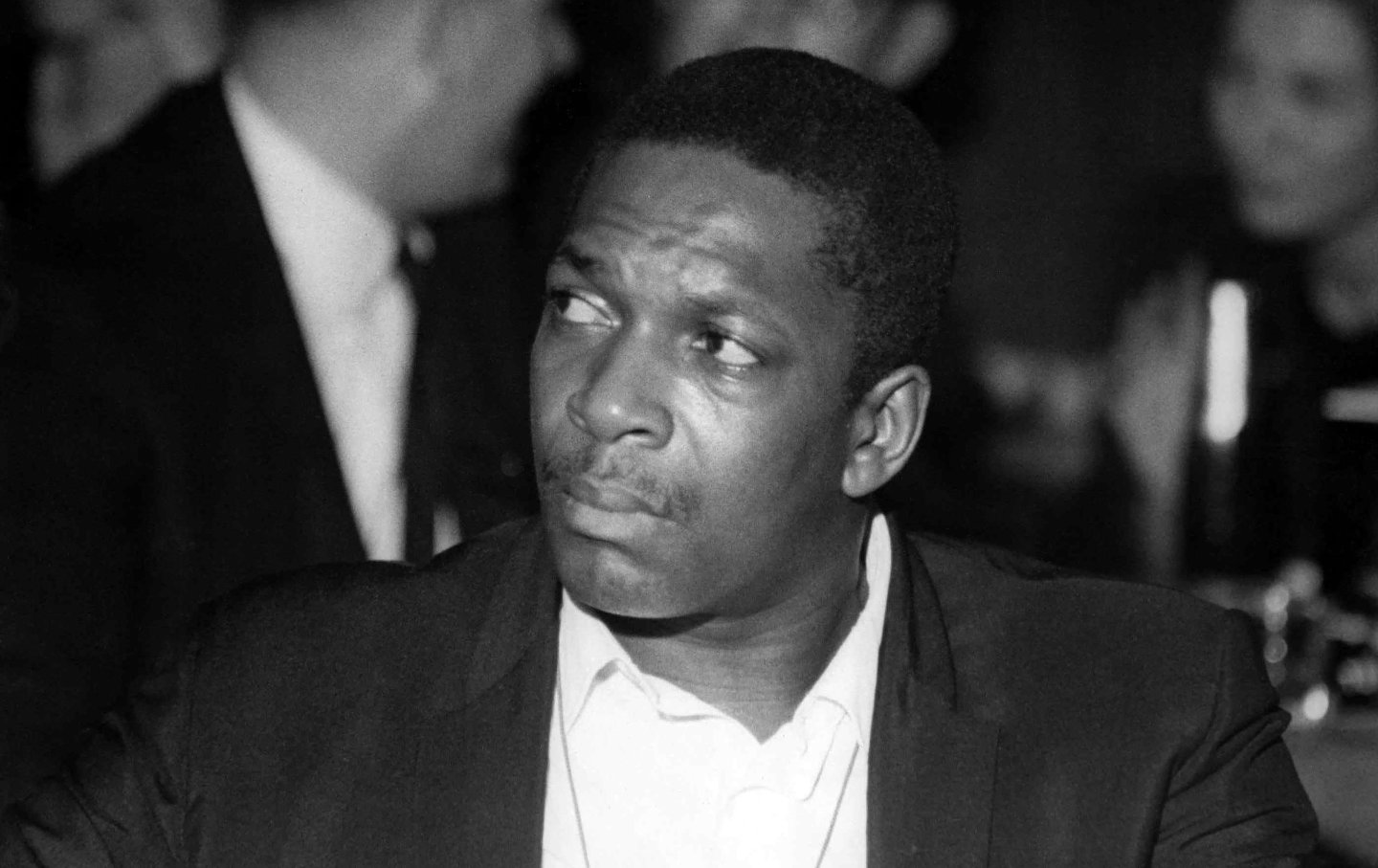

John Coltrane had only a decade’s worth of output as a leader, but he used his time wisely, leaving behind a large discography documenting a continuous dialogue between study and mastery. While that discography is one of the finest achievements in human history, it’s also a messy, mutating, and ever-growing object. Some of the Coltrane posthumous releases are essential, others less so. Certain live tapes are hunted like the Holy Grail. The latest striking addition, available everywhere as of today, is A Love Supreme: Live In Seattle, a recently discovered recording of Coltrane’s most famous composition made 10 months after the studio version. The title alone provokes an excited response from any serious Coltrane fan.

Before deciding the status of A Love Supreme: Live In Seattle—is it the Grail or not?—we should refresh our conception of the original.

A Love Supreme was recorded for Impulse! records in December 1964 and released to wide acclaim in 1965. As an iconic modern jazz album, A Love Supreme lags behind only Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue from 1959. (The albums share several intriguing details, including a rubato overture, an emphasis on modality, and the presence of John Coltrane.)

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

When asked if he listened to classical music, Coltrane replied, “The term ‘classical music’ means the music of the composers and musicians of the country, more or less, as opposed to the music that people dance or sing along with, the popular music.… There are different types of classical music all over the world.”

The word “jazz,” redolent of jive, sex, and white appropriation, has become contentious among some of the cognoscenti. Following Coltrane’s lead, we might substitute the phrase “American Classical Music,” meaning the New World blend of European classical music (harmony and song form) and African classical music (rhythm, phrasing, sonority, improvisation). To be clear, American Classical Music isn’t Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber, or Leonard Bernstein: Those wonderful composers are working within a European idiom. The true American idiom requires much more African influence: swing, the blues, probably a drum set. In American Classical Music, the practitioners make up much of their own parts.

Long-form composition is rarely suited to American Classical Music—if everyone is making up their own parts, then large-scale structural events are hard to control—but John Coltrane beat the odds. A Love Supreme is the greatest long-form composition of American Classical Music.

Four sections, 33 minutes. Just like famous European symphonies, many of which take about half an hour and are comprised of four movements. “Acknowledgement” is a groovy vamp, “Resolution” plaintive swing tune, “Pursuance” a burning fast minor blues, and “Psalm” a poem over a drone.

In European classical music, long-form composition means a lot of notes on paper. Notes on paper is part of American Classical Music, too, but there were not many written notes for either Kind of Blue or A Love Supreme. One of the saxophonists on Kind of Blue, Cannonball Adderley, said, “Miles’s band is the one band where you had to be able to read but there wasn’t any music.”

We have a basic outline for A Love Supreme in Coltrane’s own hand. It’s bare bones, hard to follow, with only a few pitches for the bass vamp of “Acknowledgement.” It’s unlikely that Coltrane ever handed out this chart to his quartet. Probably he taught the parts quickly to the musicians in the studio.

That’s a key point: A Love Supreme is not the work of one composer. It is the work of four composers. Pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison, and drummer Elvin Jones bring everything to the table. Several peaks are being reached simultaneously: four virtuosos, four composers of innovative and distinctive private languages, four wayward spirits—plus years of road time as one of the top acts in the business, refining a group concept.

How did they actually make it happen in the studio on the night of December 9? Who knows? The following year, a little bit of rehearsal chatter was preserved before the session that resulted in “Dearly Beloved,” where Coltrane tells his band, “It’s probably best if you keep the thing happening, but you can go with what you feel.”

Ah yes, that technical term, “the thing,” and that other technical term, “go with what you feel.”

McCoy Tyner said, “All black peoples of the earth always improvise their music. We never sit down and systemize everything.”

Much of what Tyner plays on the piano defies European-style harmonic analysis. Above all, the music of Tyner is a feeling. But there is also hard-core technical information in Tyner’s sounds, a melding of African pentatonic melody with American songbook standards and the blues. That technical information was crucial to Coltrane. For the big-band album Africa/Brass, Coltrane told his arranger Eric Dolphy to get the harmonies from Tyner. Coltrane couldn’t tell Dolphy himself what those voicings were. Coltrane said, “Tyner plays some things on the piano, but I don’t know what they are.”

The basic polyrhythm of 2:3—simultaneous duple and triple—comes from Africa and was always present in the tradition, but when Elvin Jones sat behind the drum kit, that African heritage was impossible to miss. At the time, Jones’s projection of polyrhythm was innovative; like Tyner, he would prove to be vastly influential. One of the keenest observers of the Coltrane quartet was fellow saxophonist Andrew White, who wrote: “Trane was structuring his music around Elvin. This was the main source of the symmetry in Trane’s music… Breath is life. The music must breathe. Elvin was the breath in Trane’s music.… It was the manipulation of standard devices that established Coltrane as a thorough improvisor as well as a spontaneous creator, but it was the Elvin Jones grammar that brought these elements into clear focus.”

Jimmy Garrison could swing as hard as anyone, with a pure guttural thump on the bass, but Garrison also knew a whole spectrum of music. Somewhat surprisingly, this most bluesy of bassists apprenticed with the decidedly non-bluesy piano geniuses Lennie Tristano and Bill Evans; he also worked comfortably with the avant-garde avatar Ornette Coleman. In time, Garrison’s a cappella bass solos would be a highlight of Coltrane’s groups in concert; his cadenzas on A Love Supreme must be the best-loved solo bass moments in all of recorded history.

Again, Coltrane didn’t give Garrison those notes. Coltrane barely gave anyone any notes. Everyone one in the quartet brought their own notes.

Because this is a capitalist society, Coltrane gets sole composer credit for the suite. He also got an advance from Impulse! and later royalties. The sidemen did not get an advance or royalties: For December 9, Tyner, Garrison, and Jones each made flat fee of $142.33. (On the following night, which included other musicians and alternate tracks that were not released, they made an additional $101.66.)

It is also true that Tyner, Garrison, and Jones were deeply inspired by Coltrane. The very night before A Love Supreme, the trio was in the same studio laying down McCoy Tyner Plays Ellington, which is a fun listen… but it ain’t no A Love Supreme.

From a 2021 perspective, it is difficult to comprehend what that creative/economic/sociological/historical moment was like. If Tyner Plays Ellington marked one boundary, then something like Albert Ayler’s Spiritual Unity from six months earlier furnished the other. No matter how innovative they were, Tyner and Jones remained committed to the community tradition of swing, song, bebop, and the blues. But Coltrane and Garrison were swayed by the upcoming ranks of avant-garde players, especially Ayler and Ornette Coleman, young firebrands who discarded tempo and harmony. Coltrane took on the techniques of Coleman and Ayler as easily as he had taken on the techniques of those he’d apprenticed with, such as Johnny Hodges, Dizzy Gillespie, Tadd Dameron, Miles Davis, and Thelonious Monk.

As Coltrane advanced, the sounds became more extreme—not that Coltrane could ever have been considered conservative. His expressionistic, almost abrasive sounds drew audible boos from a French concert with Miles Davis in 1960, and in 1962 he and Eric Dolphy sat down for DownBeat to “answer the critics” about their “anti-jazz.” Still, up to and including A Love Supreme, the swinging rhythm section remained intact. No serious person could say that Coltrane didn’t have the most swinging rhythm section around.

That particular Rubicon was crossed in late June 1965, when Coltrane added a second bass and a bevy of noisy horns for Ascension. After two long takes, Elvin Jones furiously hurled his snare against the wall. It’s a wonderful album, but we can also understand the frustration of his core quartet: Why was Trane giving up on the perfect chemistry of the four members alone together? By the end of the year, Tyner and Jones would leave the band.

Everyone involved in this story was still quite young and willful. The core quartet didn’t seem to talk about the music much; they just did it. Another live recording of A Love Supreme, from Antibes in the summer of ’65, shows quite a bit of uncertainty; they can’t even agree on the downbeat of the opening vamp. It doesn’t seem like there was any rehearsal; Coltrane probably just called it on the spot, and the band does their best to remember the forms. A Love Supreme was not then the iconic record everybody knew every note of; it was just a night in a New Jersey studio the previous December, during a period of almost frenzied activity.

During the earlier years of Coltrane’s quartet, they played familiar standards and song forms, but later in the game, Coltrane could just pick up his horn, play a few notes, like a call to arms, and away they’d go, off on the magic carpet of collective wailing (yet swinging!) improvisation. That’s what the live Antibes A Love Supreme sounds like, except that—if you know the studio version, which everyone does—a seasoned listener yearns for just a shade more control from the primary composer.

What may be most impressive about A Love Supreme: Live in Seattle is how the primary composer recalls almost every detail from nearly a year before, proving again that his vision for the greatest long-form composition of American Classical Music was crystal clear. However, it is only on the original studio session that Coltrane “reads” the text during the final section, “Psalm,” looking at his original poem with the horn in his mouth. (Once a listener realizes this is what is happening and follows the text in the liner notes, it can raise the hairs on your arms.)

Musically, A Love Supreme: Live in Seattle is right in line with the previously released posthumous Live in Seattle from the same week. The classic quartet is joined by Donald Garrett on bass and both Pharoah Sanders and Carlos Ward on saxophones. The additional members don’t know the composition, and, in truth, Tyner and Garrison don’t seem to remember it all either. Frankly, there’s too much noisy bass (they don’t even know to stop after the suite is over), but then again, Coltrane wasn’t intending to make this wonderful free-for-all an official document. It must have been thrilling to be there in the room, if not actually scary in emotional intensity, with all three horns screaming their hearts out.

Everything that Coltrane did had value, and every LP actually authorized by him is solid and listenable. He recorded Meditations with the quartet, but left that in the vaults, correctly releasing the version with Pharoah Sanders and Rashied Ali instead, for that additional heft and madness is just what Meditations needed.

Where would Coltrane have gone if liver cancer hadn’t taken him at a tender 40 years of age? One possible answer is suggested by his second tenor saxophone solo on “Out of This World” from the companion Seattle date. At the 20-minute mark, Coltrane puts down the soprano, picks up the big horn, and blows slow melodies of transcendent beauty. In this moment one can understand why he had Garrett and Sanders in the band. Those melodies are purified by fire.

There have been three high-profile “new” Coltrane releases in the last few years: Both Directions at Once, Blue World, and now A Love Supreme: Live in Seattle. It’s all great music, and anybody on the ground as a student, academic, or historian needs as much Coltrane as possible.

But we should also remember that the original albums signed off on by Coltrane himself are the definitive statement. Both Directions at Once, Blue World, and A Love Supreme: Live in Seattle appear in the streaming searches ahead of Crescent, Impressions, and Live at Birdland, and surely that isn’t right. There’s also a whiff of the same capitalist system that paid Tyner, Garrison, and Jones $142.33 and denied them any composer credit for A Love Supreme in the way these “new” Coltrane releases are touted as key releases by an industry eager to cash in on a bankable name.

This is not to say we shouldn’t have more Coltrane. We want even more! We need more! All of it should be available! Tremendous and truly essential versions of “Creation,” “Impressions,” and “I Want to Talk About You” from the Half Note in ’65 still need the Impulse! seal of approval. Another LP’s worth of unissued material from Live at Birdland is just as good as the originally issued tracks. There’s a tape of Trane and McCoy playing “Giant Steps” out there somewhere…

For the experienced listener, the Coltrane discography is a garden of unruly delights. For the inexperienced: Start with Crescent, A Love Supreme, and John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman.

If you are looking for some hip Trane that’s a little off the beaten track, something that the collectors know about but that you will have to put together yourself from different places: The June 10, 1965, session of the classic quartet yielded “Transition” and “The Last Blues.” Neither came out at the time, but they remain the peak of the old way—just a few weeks before the breach of Ascension. “Transition” and “The Last Blues.” There’s literally nothing better, anywhere, ever.