Coffee Point, Alaska—Anna Hoover and I ease up and down in limestone-colored water on a warm, windless afternoon in early July, our backs to the mouth of the Egegik River. She’s distracted, perched in the captain’s seat of her 32-foot drift boat. She glances at her phone, checking the time. The state manages fishing on a tight schedule here, opening the waters to fishermen and then closing them every few hours to let some salmon travel to their spawning grounds. We’ve got five minutes until we unspool our nets.

We sit 300 miles west of Anchorage in Bristol Bay, home to the largest, healthiest red salmon run on earth, where most wild-grown grocery-store fillets caught in the United States come from. Hoover’s parents and grandparents fished here, and she has been hauling reds from this fertile finger of saltwater for most of her 34 years.

This is her first summer as the captain of her own boat. She never doubted the decision to buy it. She’s always seen herself here, her hair pulled back in a bandanna, rubber coveralls flecked with fish scales, eyes gritty from sleep deprivation, adrenaline rising and falling with the tides that carry salmon into the nets.

“We joke how there are two kinds of people—the ones who can’t stand it out here and the ones who can’t live without it,” she says. “Fishing is in my blood.”

Still, no matter how many years you fish, she says, you always get a crackle of anxiety as you slip your nets into the water. So much can go wrong—weather, gear tangling, mechanical problems, bad timing, the catastrophe of the fish failing to show up. The risk, though, is part of the draw. “Fishermen,” she tells me, “have always been gamblers.”

For her generation of fishermen, investing here is more of a gamble than ever. Twin threats hang over this place where many of America’s salmon dinners come from: a rapidly warming climate, which has already scrambled the pattern of the seasons across vast swaths of Alaska, and Pebble Mine, a proposed open pit mine at the bay’s headwaters, which has been given new life by Donald Trump’s administration. Many who live and fish here, including Hoover, worry that once the mine is built, pollution is inevitable and that together these two forces could destroy this rare, pristine ecosystem, threatening salmon, communities, and whole ways of life.

“I think of generations. So many people in the fishery have learned it from their families and want to pass it on,” Hoover says. “Around the world, people have disrespected salmon populations and their environments to the point where they are extinct or they are farmed. This place doesn’t have that—yet.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Hoover maneuvers us into position. Two crewmen stand ready on the deck. One is a high school English teacher with a toddler at home, the other a high school student—a good kid who never gets tired. There isn’t room to mess this up. They have to make money this summer.

At 4:45 precisely, Hoover motors forward. Her net sails into the sea.

Make a backward “L” with your right hand. Now rotate your arm as if you’re looking at a wristwatch, so that the web between your thumb and index finger faces your body. Your hand will look like a rough map of Alaska, with your thumb as the southeastern panhandle and your index finger as the Alaska Peninsula, which stretches toward the Aleutian chain.

Bristol Bay is tucked between your index and middle fingers, a wide body of water fed by a network of rivers—among them the Cinder, Egegik, Igushik, Kvichak, Meshik, Nushagak, Naknek, Togiak, and Ugashik—and dozens of lakes, large and small.

For millennia, several Alaska Native groups—the Athabascans from the interior, the Yup’ik people from the southwest region, and the Aleuts from the southern coastal area—came here to fish. Commercial fishing began in the late 1800s, and the bay remains a rare jewel in a network of Alaska fisheries that are increasingly challenged by climate change. Roughly 38 million red salmon return to the bay every year, according to the Bristol Bay Regional Seafood Development Association. When they do, small fishing operations like Hoover’s pop up to catch them over about six weeks of summer, a burst of industry that employs 14,000 people and generates $1.5 billion in revenue.

Fishing is always volatile. The annual earnings in Bristol Bay might increase or decrease by $100 million, says Garrett Evridge, a fishing economist in Anchorage. But recently, fishing in the bay has been more lucrative than ever, defying patterns elsewhere in the state. Earnings more than doubled from 2015 to 2018. Some science indicates that warmer water in lakes and rivers has sped up the life cycles of young salmon, sending them out into the sea sooner, increasing their abundance. Scientists aren’t sure what that might mean over time.

“There is anxiety that the seasons have been too good and that the bay is headed to a reset or just back to historical averages,” Evridge says. “This is tough if you’ve just sunk your life savings into a boat and permit.”

Hoover grew up fishing out of Egegik, a tiny village on the southern part of the bay. Her great-grandfather fished halibut in the Gulf of Alaska before he settled in the region. Her grandfather ran a cannery. In the off-season, she lives in Naknek, working as a filmmaker.

Hoover bases her fishing operation out of a camp in Coffee Point, which sits on land acquired by her husband’s father after World War II, just across the river from Egegik. The camp has a big kitchen and living hall with bunks for a crew of 16. A collection of wood-sided outbuildings rises from the dunes, among them a massive shed for working on machinery, a tidy fleet of cars and ATVs, and a small cabin where Hoover and her husband, Eddie Clark, stay with their daughter, Amlia, who is 3. The workdays run around the clock. Hoover fishes, sells her catch, rides home, eats, sleeps for a few hours, and then heads back out.

“At the beginning, it’s exciting because you know the fishing is picking up,” Hoover says. “Once you’re in it and doing two tides a day for two weeks, you’re wiped out. It’s a test.”

From her seat above the main cabin of the boat, Hoover eyes the arch of the net, white corks on the water like a string of pearls. Soon, splashes and flashes of silver scales churn along the line, just under the surface. There’s movement on all the boat decks around us.

When the fish hit, Hoover says, you get an electric current in your heart. You marvel at your luck, at the abundance of the bay, fish thumping on the deck like coins pouring out of a slot machine. There’s a boat somewhere out there called Little Casino, she says. Lots of boats have names like that.

“If you are lucky, $50,000 worth of salmon can be caught in a day,” Evridge says later. “And all fishermen think they are lucky.”

To get to Coffee Point, Hoover must fly an hour west of Anchorage to King Salmon and then drive 10 miles to the fishing hub of Naknek. From there, she flies her own plane to the camp.

Before she took a photographer and me on the boat, Hoover came to fetch us in a low-wing Piper Cherokee 140 with Amlia in a pink booster seat in the back. The plane is just large enough to seat four people and carry a few bags. It rattled down the rocky Naknek airstrip and lofted us into the air. We cruised low along the coast over the flat, green country, braided through with streams and rivers, stippled with too many lakes and ponds to count. This is the world’s purest salmon country.

Throughout the Pacific Northwest over the last 50 years, in-river problems like dams, pollution, and deforestation have harmed many salmon runs. In Alaska, too, the fisheries have suffered. Over the last decade, king salmon—the largest kind, prized for their fatty meat—have been consistently smaller, and their returns have fallen below expectations, for reasons scientists can’t explain. Towns built around king salmon fishing tourism, like Kenai, south of Anchorage, have had to reenvision their economies. Locals in small river communities who relied on kings to fill their freezers for winter have had to switch to other species. In Southeast Alaska, commercial fishing forecasts have been grim.

Red salmon had almost always been plentiful, but last summer a number of stalwart red fisheries in the Gulf of Alaska faltered. Returns came in late and weak; others barely came in at all. Fishermen used to four decades of strong fishing on the Copper River came home empty-handed. Off Kodiak Island, at the beginning of the season, boats pulled in nets full of jellyfish and nothing else. The starkest losses came in Chignik, a small Alaska Native community on the Alaska Peninsula, where commercial fishing is the only economy. From 2013 to 2017, the local fleet harvested an annual average of 18 million pounds of salmon, worth more than $15 million. But last year, the fleet earned less than $5,000, Evridge says. The state declared it an economic disaster.

Scientists have been cautious about saying what happened with reds last year, insisting they need more time to study it. But many suspect the anomalies may have to do with rising ocean temperatures. A large pool of warm ocean water called the Blob moved north from Mexico in 2014. Blooms of toxic algae followed. Birds and mammals washed up dead.

Yet even with last year’s weak returns elsewhere, Bristol Bay’s fishing remained strong, with fishermen harvesting some 232 million pounds of salmon worth nearly $281 million, according to the Alaska Department of Fishing and Game. The reason, according to Tom Quinn, a University of Washington professor of aquatic and fishery sciences who has spent more than 30 years studying Bristol Bay, stems from the remote bay’s particular geography and topography, which makes it uniquely positioned to resist climate change. The lakes and rivers around it are fed by snowmelt, rain, and glacial runoff, and they have different depths and temperatures. This provides a diverse set of freshwater habitats for young salmon.

“It’s undammed and unpolluted,” Quinn says. “It’s not quite as God made it, but it’s in very, very good condition.”

Moreover, he adds, there isn’t competition from Japanese fishermen as there once was, and the area is well managed by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

Still, the threat of climate change looms large, hovering at the edge of every fisherman’s consciousness. This past summer was the hottest in Alaska’s recorded history, with record-breaking temperatures and unprecedented drought. Quinn’s team reported the warmest temperatures it has ever seen in its decades studying the bay. Plus the flow of water in the rivers is extremely low.

“We will have to see how the salmon fare under these conditions,” he says. If it becomes the new normal, “there is reason to be very concerned.”

Hoover and I watch the big metal spool on the boat deck turn, reeling in the net. The fish come in C-shaped and muscular, with scales the color of moonlight, suspended in their last conscious moment. Mouths open, needle teeth. The crewmen shake them loose, each one a little puzzle of tangled line and fins. The fish pile around their boots. The deck glitters with a thousand scales.

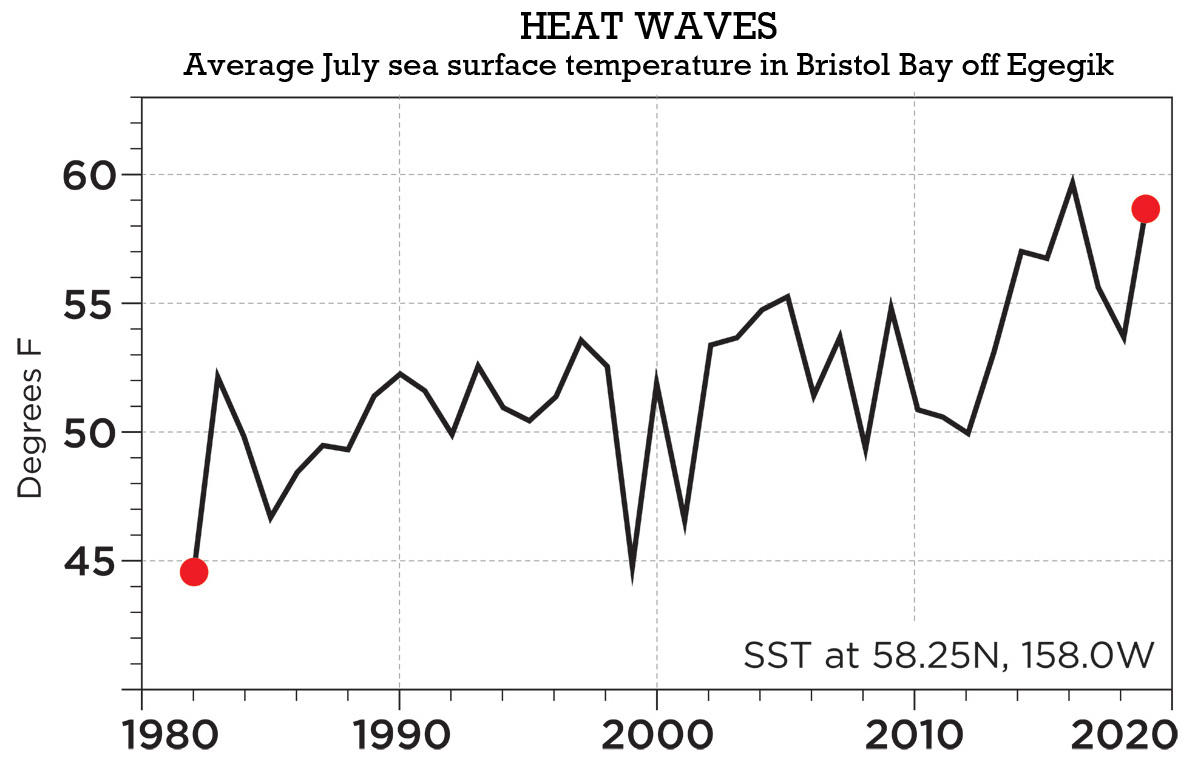

The average sea surface temperature outside Egegik in July has trended higher each decade since Hoover started fishing in elementary school. Today it is nearly 60 degrees, roughly 10 degrees higher than it was at the same time 30 years ago, according to the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy. In August it reached 62.7 degrees, the highest temperature since records have been kept.

“Sometimes the fish are so warm when you pick ‘em up, you can feel it through your gloves,” Hoover says.

Nature has become erratic in Alaska, with each season seeming to bring eerie new surprises. The state had never seen a year like this. In the spring, river and sea ice vanished earlier than ever before in many places. Temperatures soared 10 to 20 degrees above normal. Summer brought a severe, unprecedented drought. Anchorage hit 90 degrees for the first time on record. Birch leaves turned brittle and fell from the trees. Fires shut down the highway system for days, and one of them north of Wasilla chewed into a neighborhood, turning 51 homes to ash. Smoke hung over almost the entire state in late June and early July.

Scientists are still sorting out the signs of trouble in the ocean. Seals, krill, seabirds and thousands of blue mussels washed up dead on the beaches. Hundreds of salmon perished in the lower Kuskokwim River, where water temperatures reached the 70s, before they’d had a chance to spawn. Scientists theorized the fish died from heart attacks caused by the heat. Later in the season, Hoover heard about Bristol Bay fishermen rescuing salmon from warm, shallow river water, carrying them in bags upriver toward their spawning grounds. By September, another mass of warm water similar to the Blob had formed off the Pacific Coast and was expected to move toward Alaska.

Out on the bay on this early-July day, though, there’s nothing but pink sky and the far-off sight of grassy muskeg atop sandy cliffs. There’s also fish. For three hours, we watch the crew slide their bodies across the deck into the cool, foamy water of the hold. The boat is heavy with them. In the captain’s seat, Hoover chews dried apples and sips tea. We pull in the final net of the day.

Climate change, for all its disruptions and distortions, isn’t the only threat lurking over the bay. Far more menacing, from the point of view of Hoover and many others, is the prospect of Pebble Mine. The controversial extraction operation was first proposed 30 years ago. Hoover isn’t an emotional person, but if you ask her about it, her voice thins.

Pebble Mine is a large copper, gold, and molybdenum open pit mine set to be located in the Kvichak and Nushagak water systems, which feed into Bristol Bay. In its current iteration, it is slated to cover 8,000 acres, including a 608-acre pit that’s almost 2,000 feet deep. This version, which is smaller than previous ones, would produce 1.4 billion tons of materials over 20 years.

Environmentalists, scientists, and fishermen have warned for years about the dangers that would be posed by any mine in the area. The process of extraction would generate a massive amount of acidic toxic water that must be kept out of the larger ecosystem. The mine development would require building roads, power lines, pipelines and ports on undeveloped land, putting new stressors on fish habitat, says Lindsey Bloom, a longtime fisherwoman and a strategist with Salmon State, a political advocacy group opposed to the mine. “It directly impacts thousands of years of subsistence relationships with the landscape, tens of thousands of jobs, billions of dollars a year in economic activity at regional, state and global networks,” she adds.

There was a time during the Obama administration when it seemed that the anti-Pebble forces won and the project would be stopped. In 2014 the Environmental Protection Agency issued what amounted to a preemptive veto of the mine proposal after determining that it would “pose significant risks to the unparalleled ecosystem”; later that year, a successful voter initiative gave the state legislature the power to approve or reject the mine, putting up an additional hurdle. Along the way, Northern Dynasty Minerals, the Canadian company behind the mine, lost several of its major backers.

But now, as with many once-stalled extraction projects in Alaska, Pebble Mine is moving forward again, in a more modest form. In late July the EPA’s leadership formally reversed the agency’s 2014 position, reportedly after Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy, a Trump ally and mine supporter, met with the president on Air Force One. (Notably, EPA scientists still object. They’ve submitted over 100 pages of comments critical of the newest plan, saying that substantial concerns remain about adverse effects on the ecosystem.) The partnership now developing the mine has been pushing to get as far as it can through the federal permitting process before the next presidential election.

For many of the mine’s opponents, the greatest concern is the possibility that the dam designed to contain a basin of concentrated toxic mine tailings could fail. They talk about other mine catastrophes, like the one in Brumadinho, Brazil, in January that buried hundreds of people and the Mount Polley disaster in British Columbia in 2014 that spilled a torrent of toxic water into neighboring lakes and rivers. Though the current mine plan is smaller than before, many say that once the mining begins, the size of the operation will expand.

I talked about that with Cameron Wobus, a geomorphologist and consultant who specializes in assessing the hydrologic impacts of mining. He was hired by the Nature Conservancy, an international conservation group, to study the Pebble Mine proposal and presented his findings to the state legislature in April. He says that Pebble’s tailings storage facility is 10 times larger than the Mount Polley mine’s and more than 50 times larger than the Brumadinho mine’s. The dam has to survive forever, but the plans project the odds of its failure only over 20 years, he says.

Even barring a large disaster, smaller-scale pollution would be almost impossible to prevent, Wobus continues. “They can’t capture and treat all their contaminated water…. It is not a stretch to say mines always leak. Water quality downstream of mines is never what it was before you built the mine.”

As currently planned, Pebble Mine would have massive water treatment needs, he adds. He says it would be the biggest mine-water treatment plant in North America.

A spokesman for the Pebble Partnership, Mike Heatwole, states that the group “fundamentally disagrees” with the claim that all of the contaminated water produced by the mine cannot be treated and contained. He stresses that the mine’s footprint has shrunk and that more safeguards have been put in place to prevent pollution and help address environmental concerns. The facility is designed to “stand the test of time,” he adds. “We continue to try to reach out to [fishermen] and try to share as much as we can, because we do understand people’s concerns.”

The EPA is now working with the Army Corps of Engineers to determine whether to grant the permit that Pebble needs under the Clean Water Act. The EPA can still raise concerns, but that may not stop the proposal from going forward. “The cynic in me says the permit will go through,” Wobus says, “but I still have hope that science and reason could actually prevail.”

Some communities in the region support the Pebble Mine project because of the jobs it would provide. But in Naknek, anti-Pebble signs are everywhere—at the engine repair shop and the bar and on the bumpers of old trucks, right next to faded Sarah Palin and Trump stickers.

Hoover pulls her boat into a long line at the tender, a larger vessel that will hoist the fish from our holds and weigh them. On the decks around us, crewmen mend nets. I count a half-dozen anti-Pebble flags catching the wind.

After a long while, it’s our turn. The fishermen on board the tender are red-eyed and wired, facial hair gone feral. They scribble the weight of our fish on a sticky notepad and shovel them into the hold. Wildfire smoke makes the sinking sun glow crimson as a salmon egg.

Friends have gotten law degrees to help fight the mine, Hoover tells me. She has written a dozen letters to officials involved with the permit process. “We’ve all testified so many times,” she says.

Still, the proposal moves forward. Assuming it survives the federal process, it will likely see a number of court challenges. Next will be a state permitting process. If the plan proves successful, the mine could begin operations within the next decade.

“Maybe I could get my boat paid off,” Hoover says, “before it really starts up.” What she wants most of all, though, is for Amlia to know this life, too, and to be able to take it on someday.

With the boat finally empty and our eyes dry with smoke and salt, we rock home in the dusky light, passing lines of fishing boats moored up, the crews napping in their cabins.

Hoover tells me she listened to a story on NPR recently about how partisan the United States has become. “There’s a fracture between two ways of thinking in the country,” she says.

There’s a fracture at the center of life in Alaska, as well. The oil revenues that used to pay for state government have declined, and the state budget is in crisis. Alaskans all have a deep allegiance to the wild place. But there are also the rich resources that bring people here and help them stay. Alaskans aren’t usually staunchly on one side or another, but still they find themselves in conflict. How much development can be done without risking the core of the place? The sides have gotten so far apart.

“For me, a healthy ecosystem is sacred,” Hoover says. “I respect it. If I could communicate it well enough, I feel that we wouldn’t still be having this conversation.”

Hoover’s drift boat comes to rest offshore from the fish camp. Clark, her husband, motors out to us in a smaller boat. As we glide over shallow water toward land, we see Amlia’s face in the square of Clark’s truck window on the beach. She wiggles out of the open door, scampering to greet us. Hoover has a salmon to feed the crew. Amlia reaches for it, insisting she is big enough to hold it. Hoover gives it to her, and the little girl leads us back to camp, the head of the salmon hoisted high, its tail drawing a line in the sand.